Partnerships

Nuart Aberdeen 2024

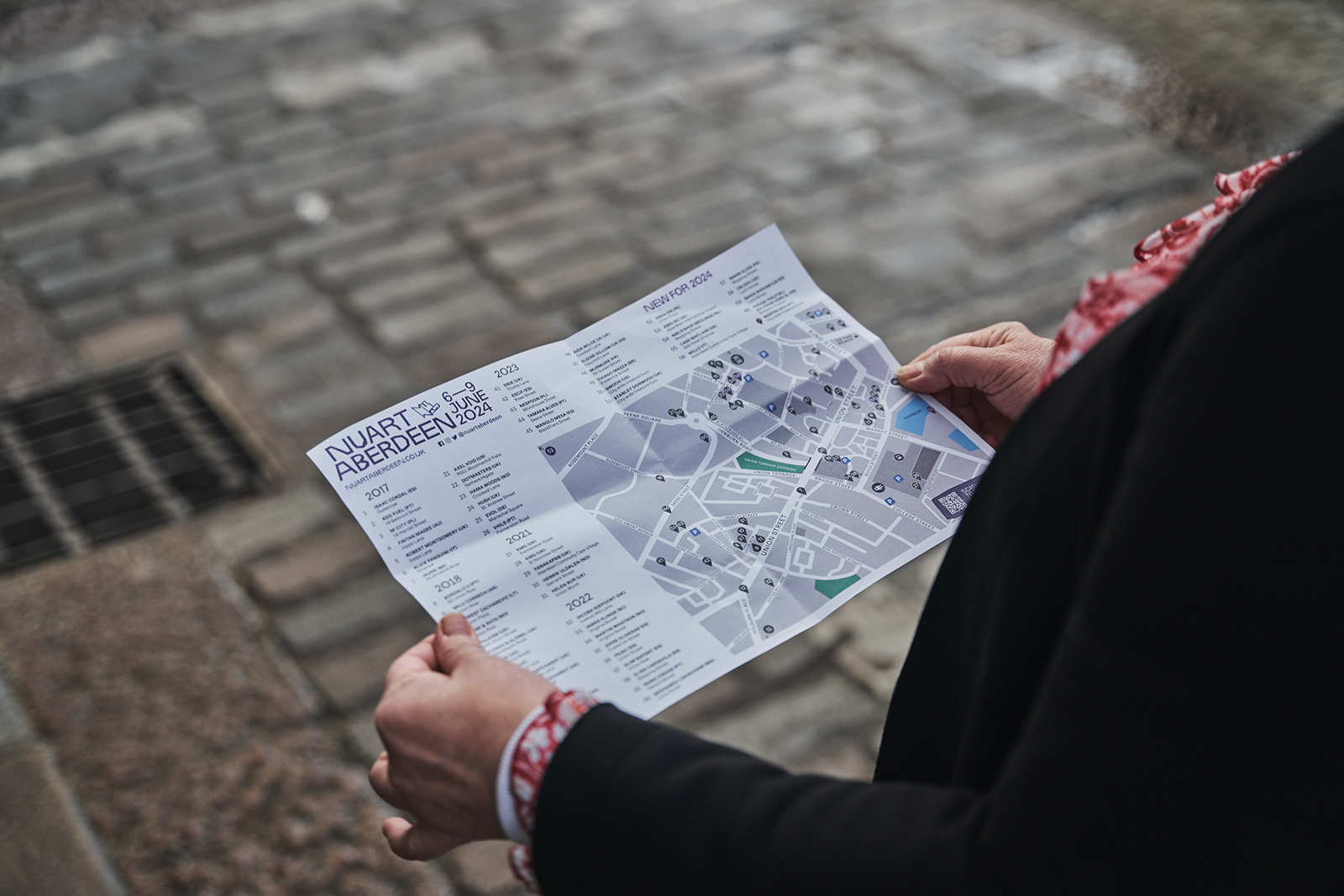

Nuart Aberdeen 2024 saw a fresh influx of public artworks appear on the streets of the Granite City.

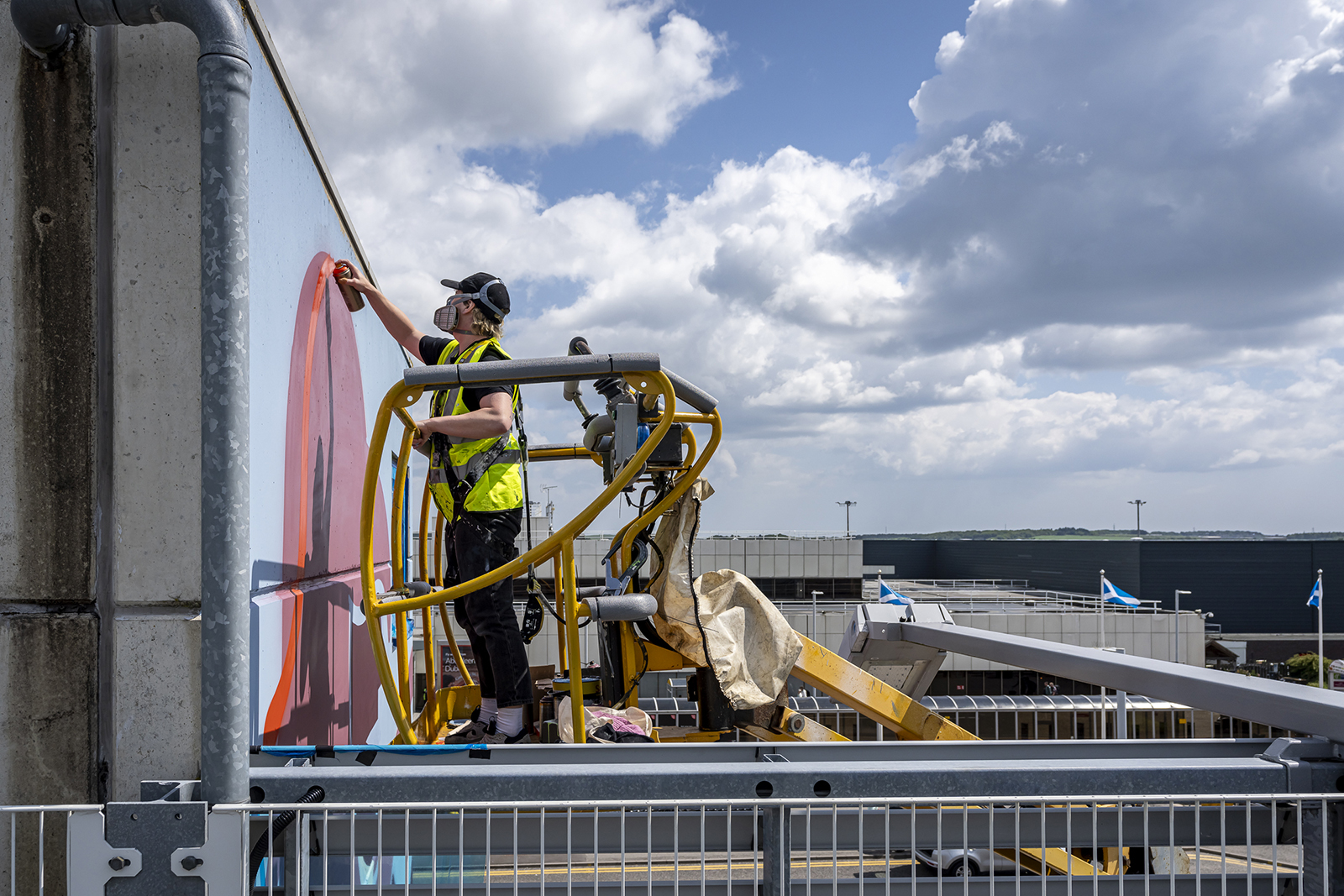

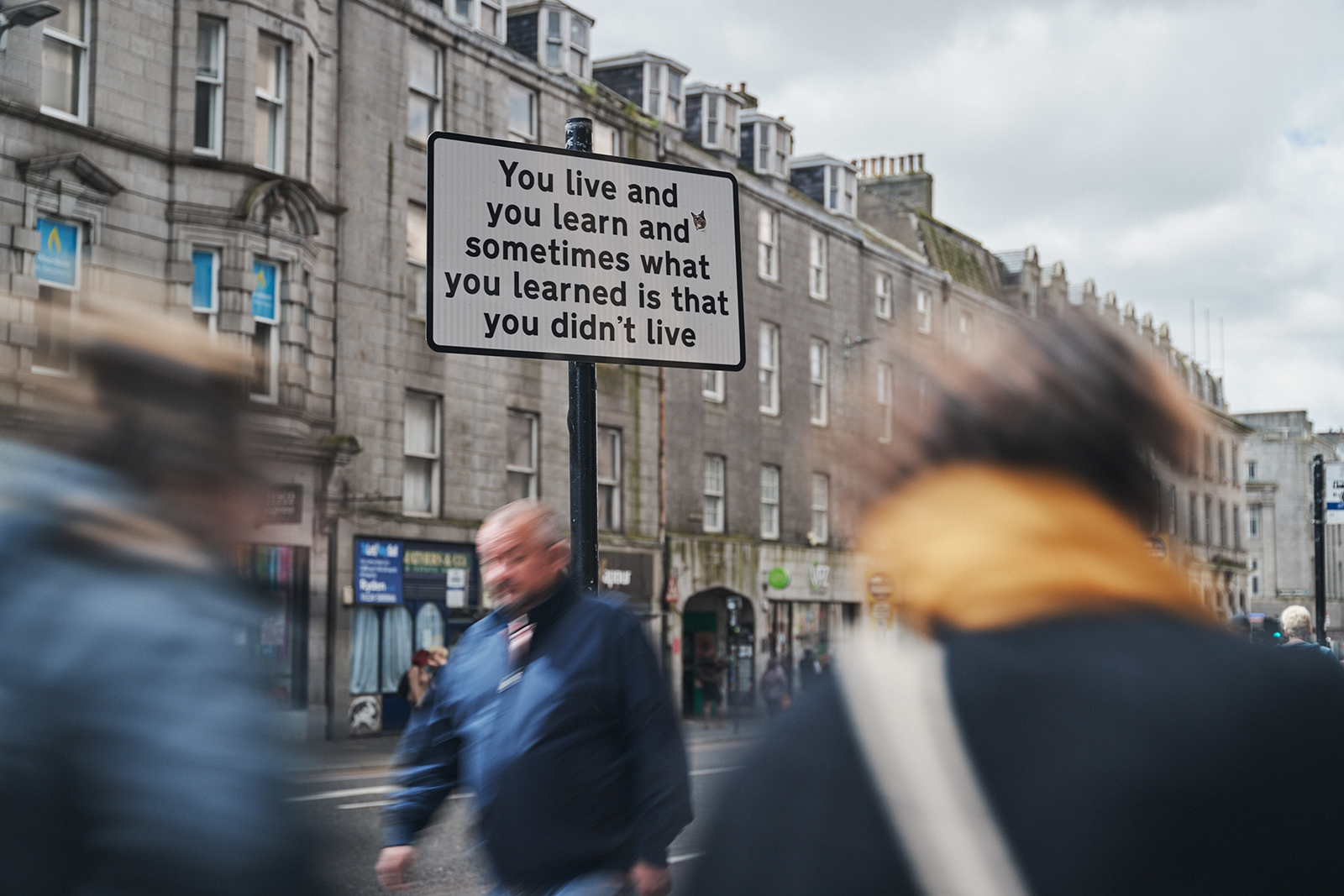

Monumental and expressive, the painterly portrait by Case Maclaim (aka Andreas Chrzanowski); Cbloxx (aka Jay Gilleard) created their signature aerosol magic and mystery; HERA (Jasmin Siddiqui) delivered a truly towering artwork that nevertheless communicates care and tenderness; KMG’s bold, beautifully pared-down characters at the airport transformed non-descript buildings into visual clarions; Mahn Kloix introduced another of his ‘contre-feux’ figures that seek to give a voice to whistle-blowers, refugees, activists and the like; Millo (Francesco Camillo Giorgino) combined breath-taking detail, urban energy and subtle allusions to myriad hidden stories; Neil “Shoe” Meulman brought his distinctive ‘calligraffiti’ to the festival; Wasted Rita’s faux street signage seeded the city with poetic, wistfully critical comments and artist and muralist Molly Hankinson had the singular honour of marshalling Aberdonian ‘kids’ (aged 9 to 99) in making the mother of all chalk floor drawings.

Such are the new visual delights and provocations added to the ever-changing Nuart trail of public works. Weekly tours of the art continue throughout the summer months but as the curtains came down on Nuart Festival’s core weekend of films, lectures, presentations and panel discussions, it seemed a good idea to catch up with Nuart Festival founder and director Martyn Reed and Nuart Plus co-convenor and Nuart Journal editor Susan Hansen.

21.06.24

Words by

NUMUSIC

NUMUSIC

Martyn Reed London 2001 ©Nuart

Martyn Reed London 2001 ©Nuart

Martyn Reed & Susan Hansen, Lisbon, Street Art & Urban Creativity, 2017 ©Nuart

Martyn Reed & Susan Hansen, Lisbon, Street Art & Urban Creativity, 2017 ©Nuart

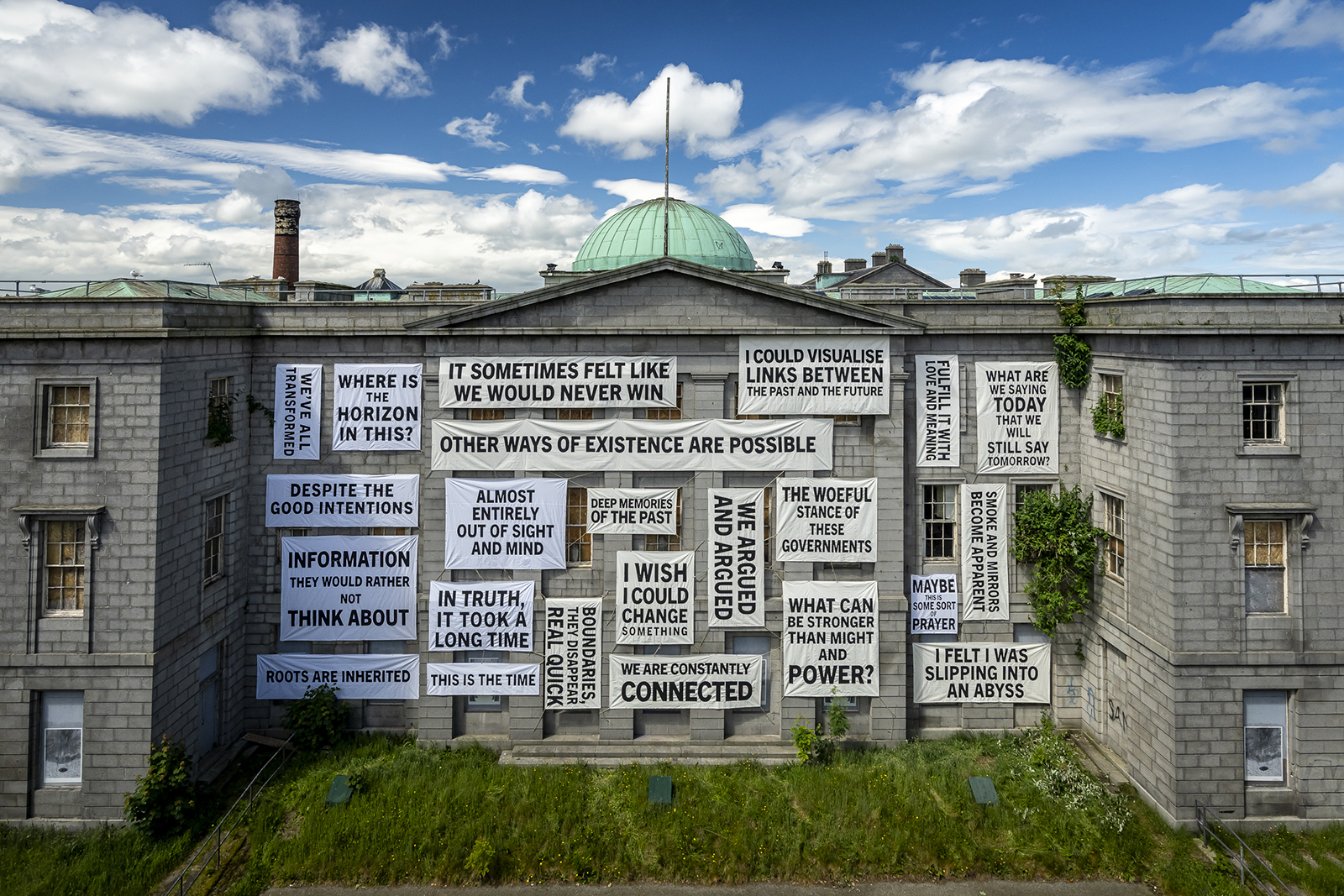

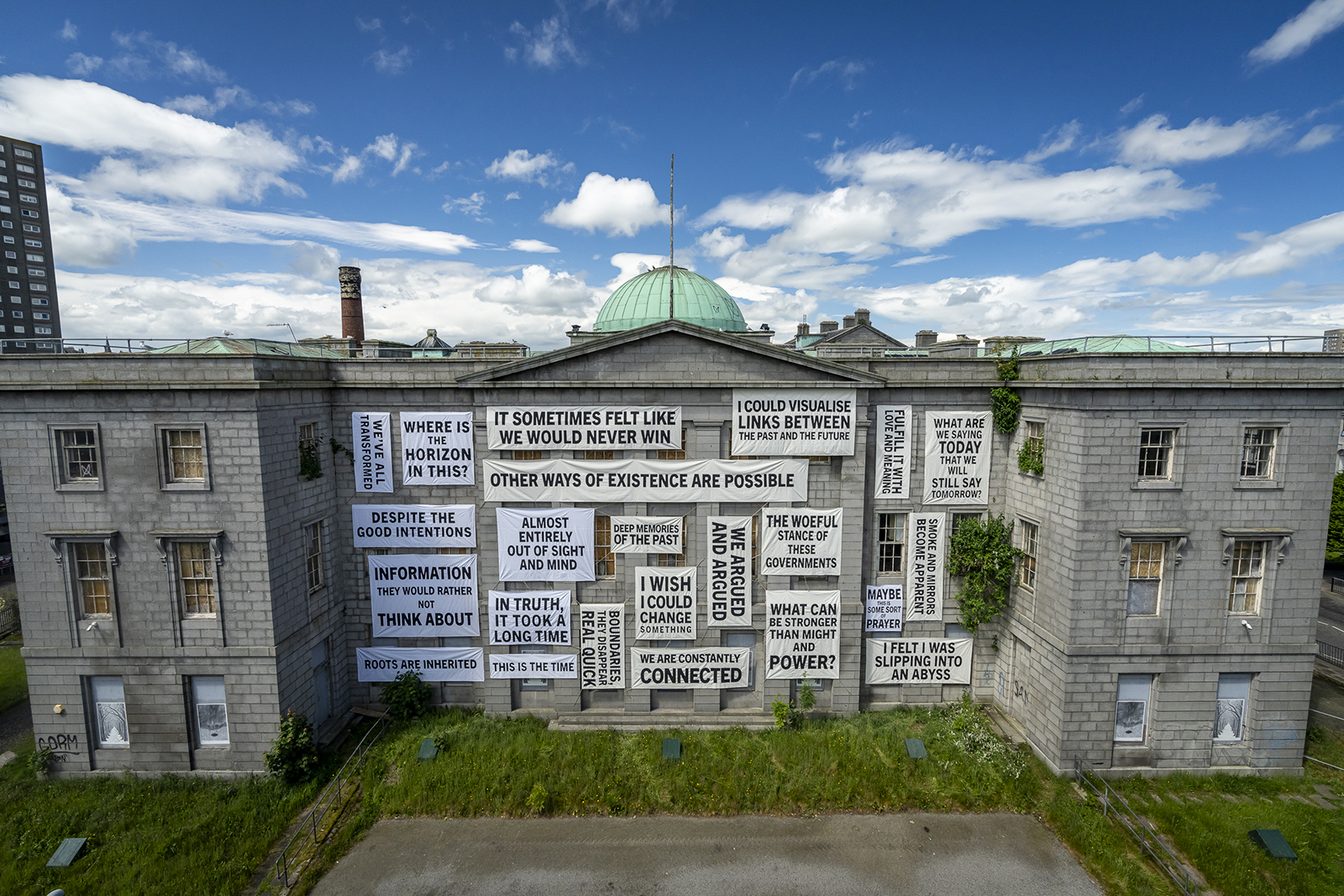

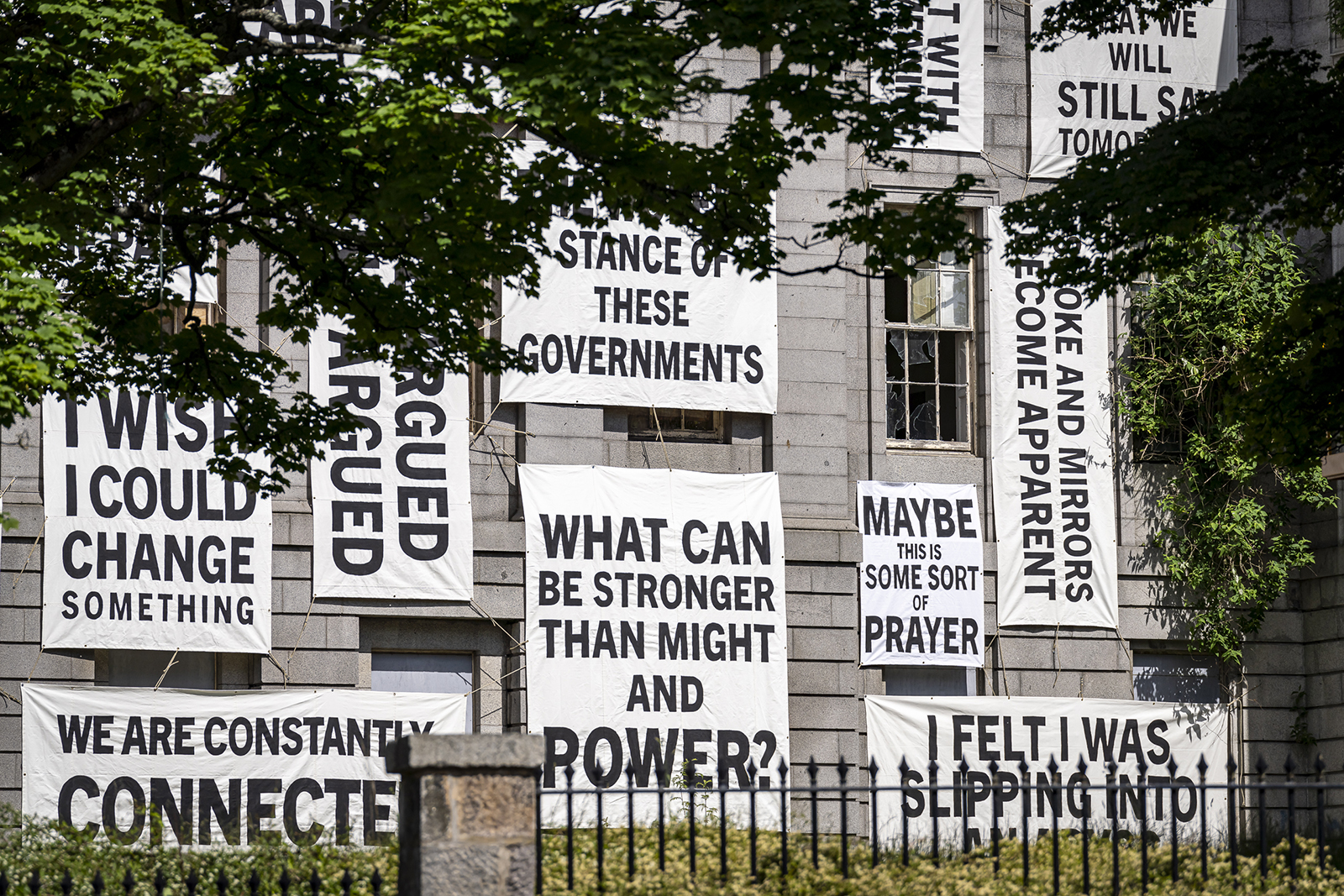

Bahia Shehab (LB-EG)

Bahia Shehab (LB-EG)

Cbloxx (UK)

Cbloxx (UK)

Hera (DE-PK)

Hera (DE-PK)

Cbloxx (UK)

Cbloxx (UK)

©bktfoto

©bktfoto

©bktfoto

©bktfoto

©bktfoto

©bktfoto

©conorgaultphotography

©conorgaultphotography

©conorgaultphotography

©conorgaultphotography

©conorgaultphotography

©conorgaultphotography