Your Space Or Mine

14 Years of Hurt

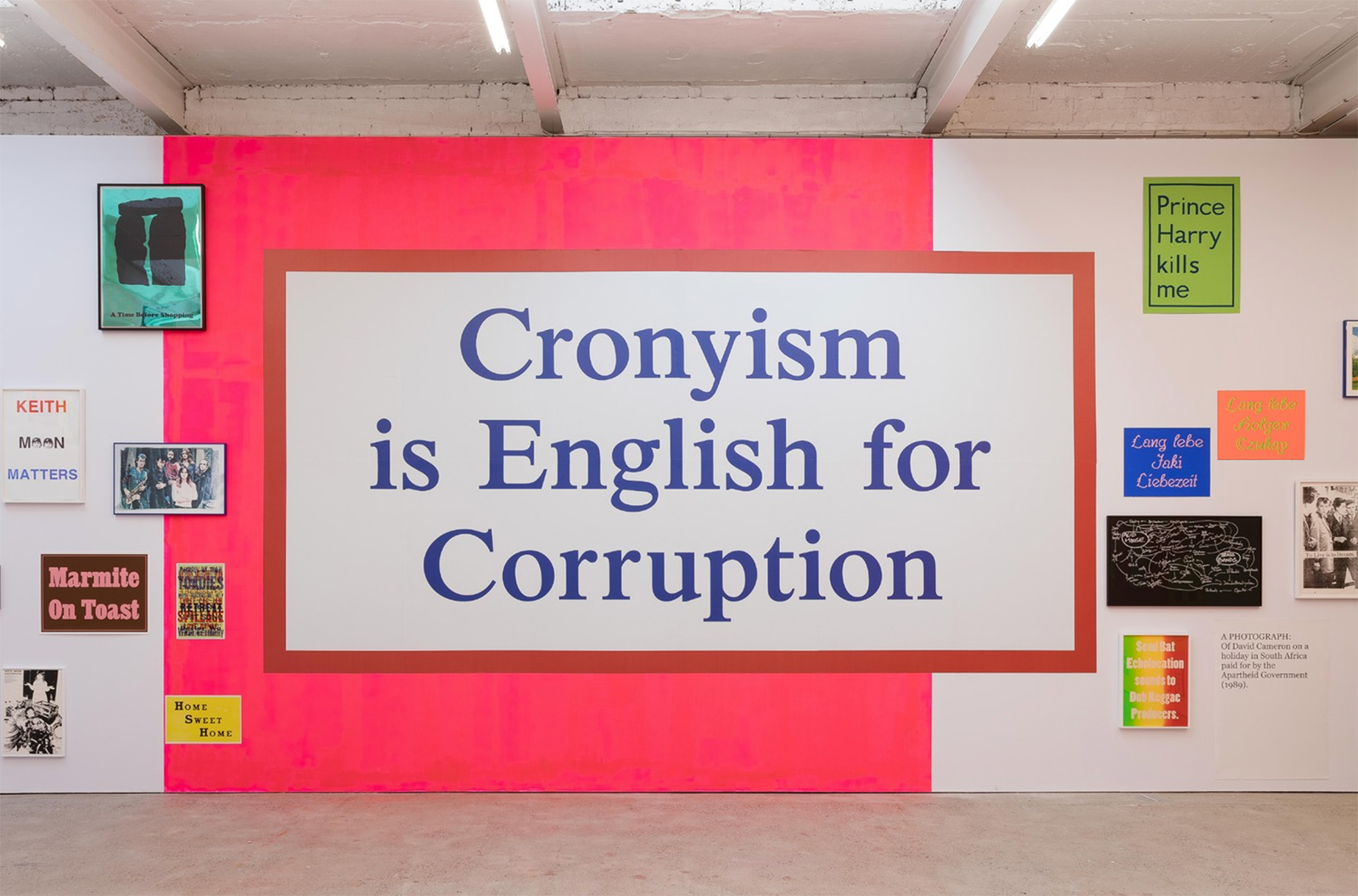

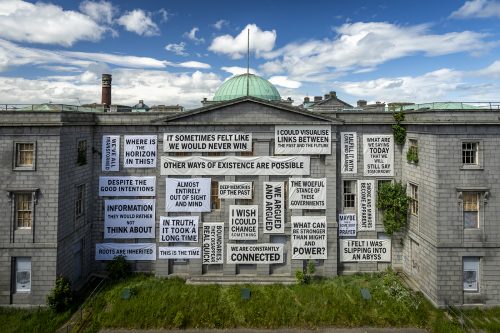

Jeremy Deller has been making poster art ever since he enrolled onto a screen-printing class in 1994. Posters are part of his work, alongside films and artworks that reflect recent history, and which often involve people doing things, for example his re-enactment of the Miners’ Strike-era

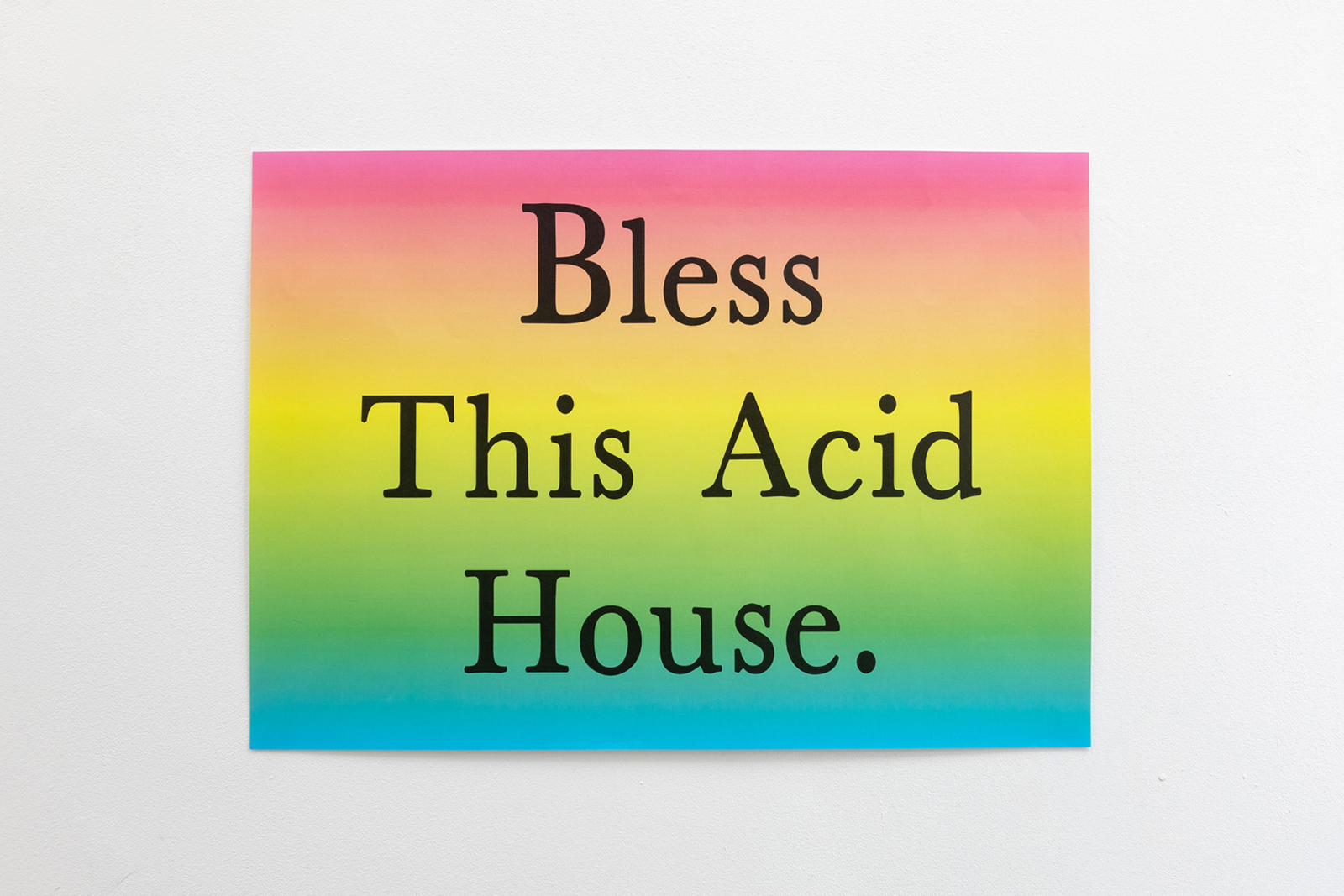

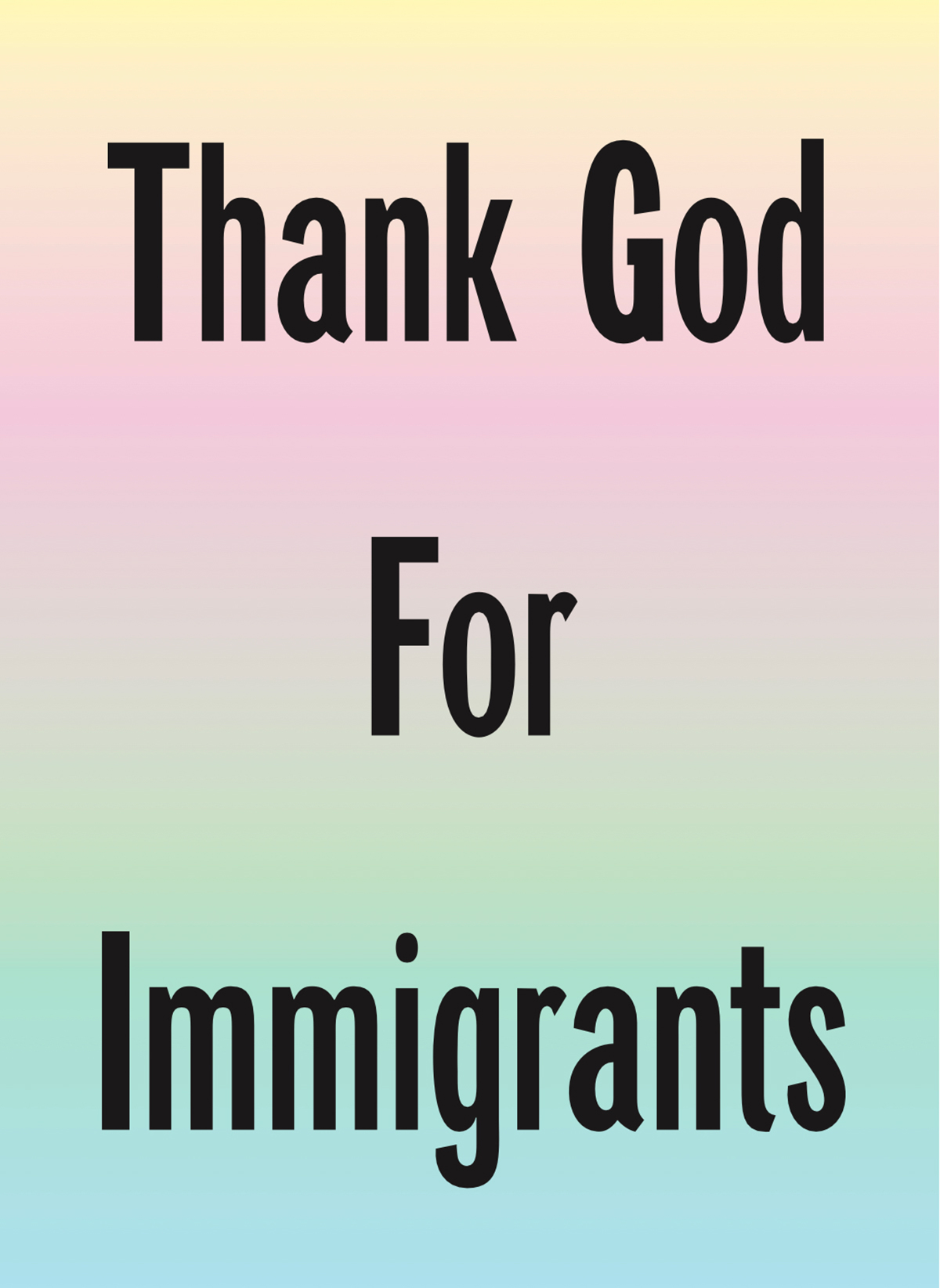

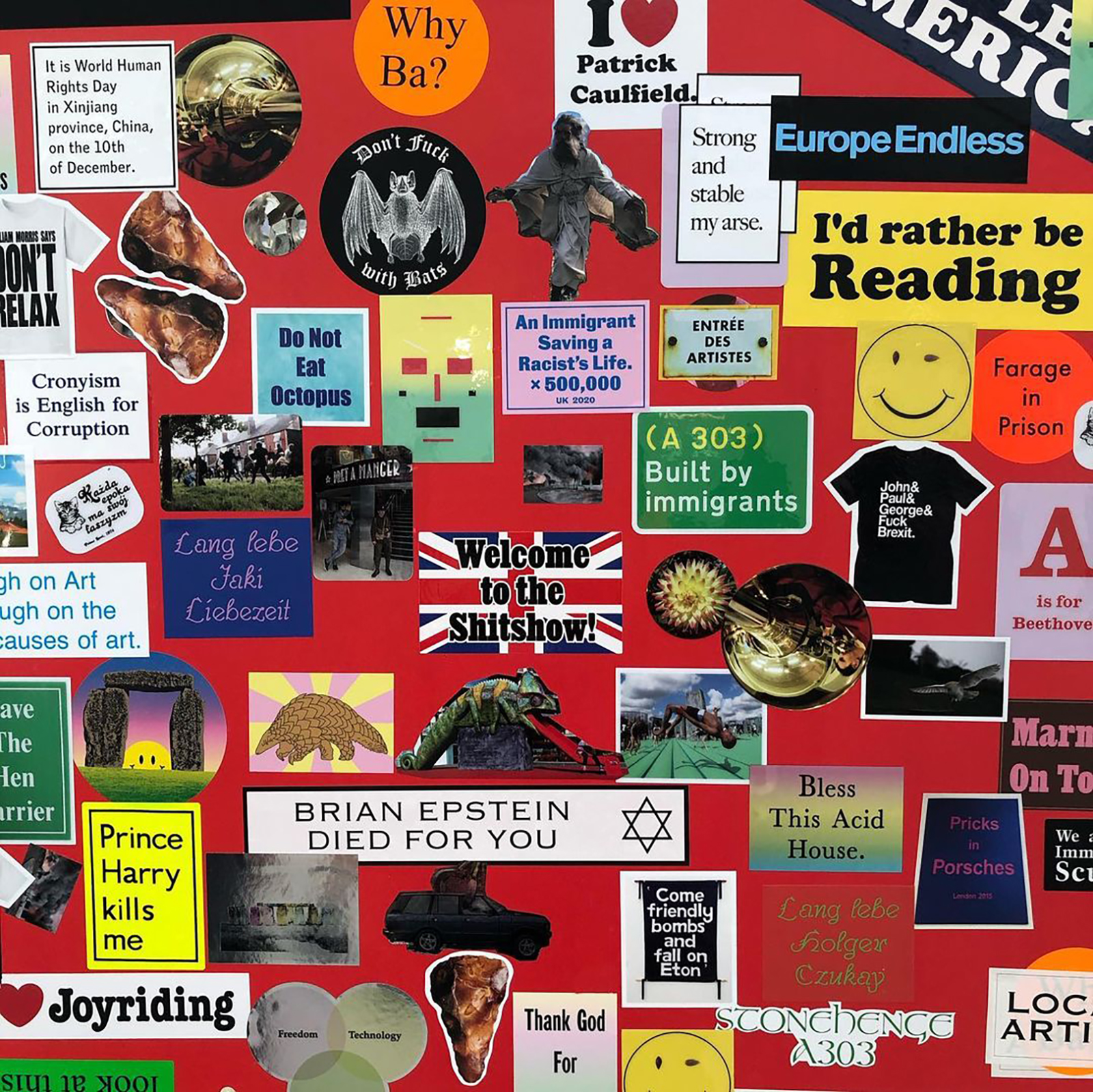

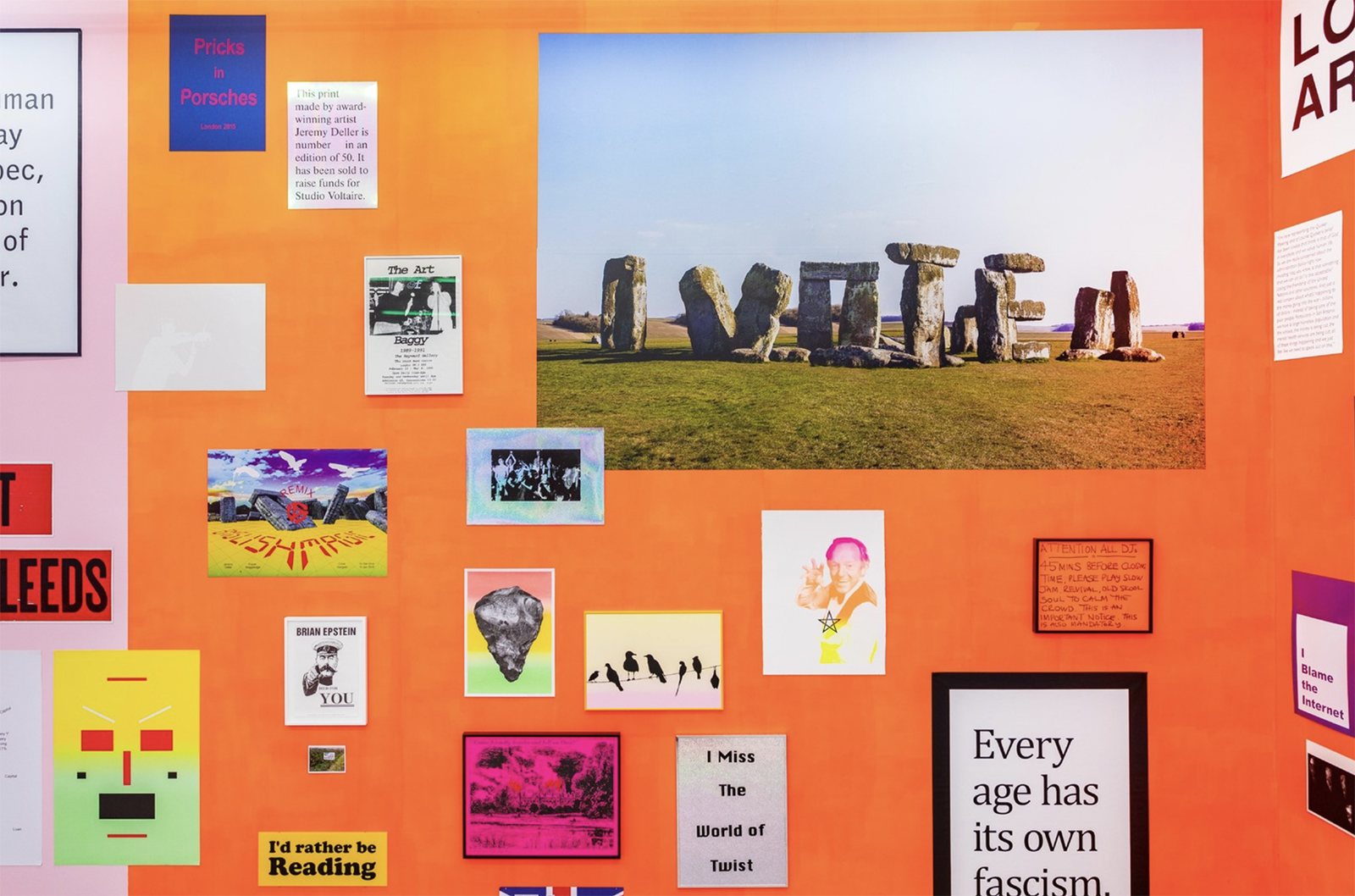

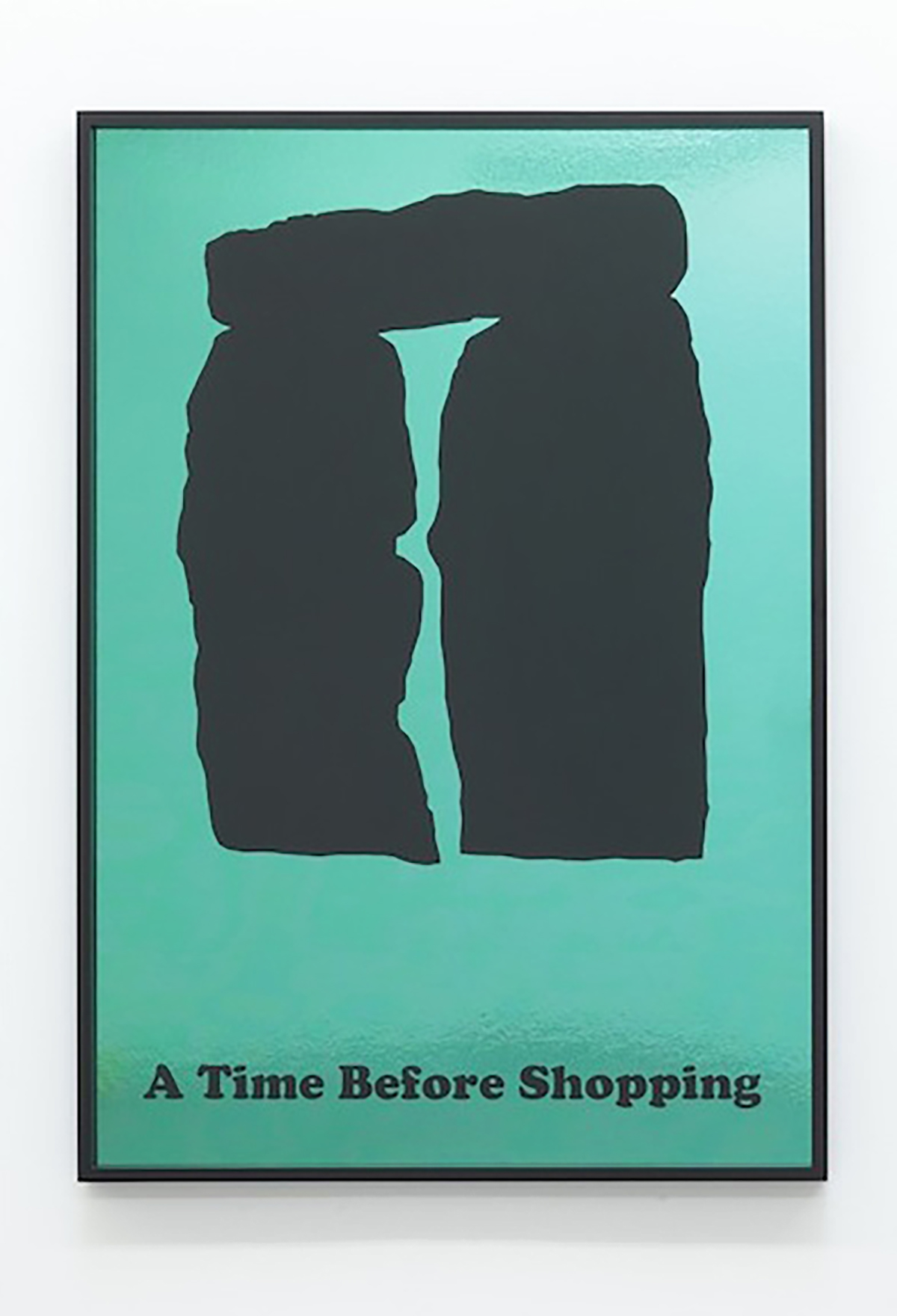

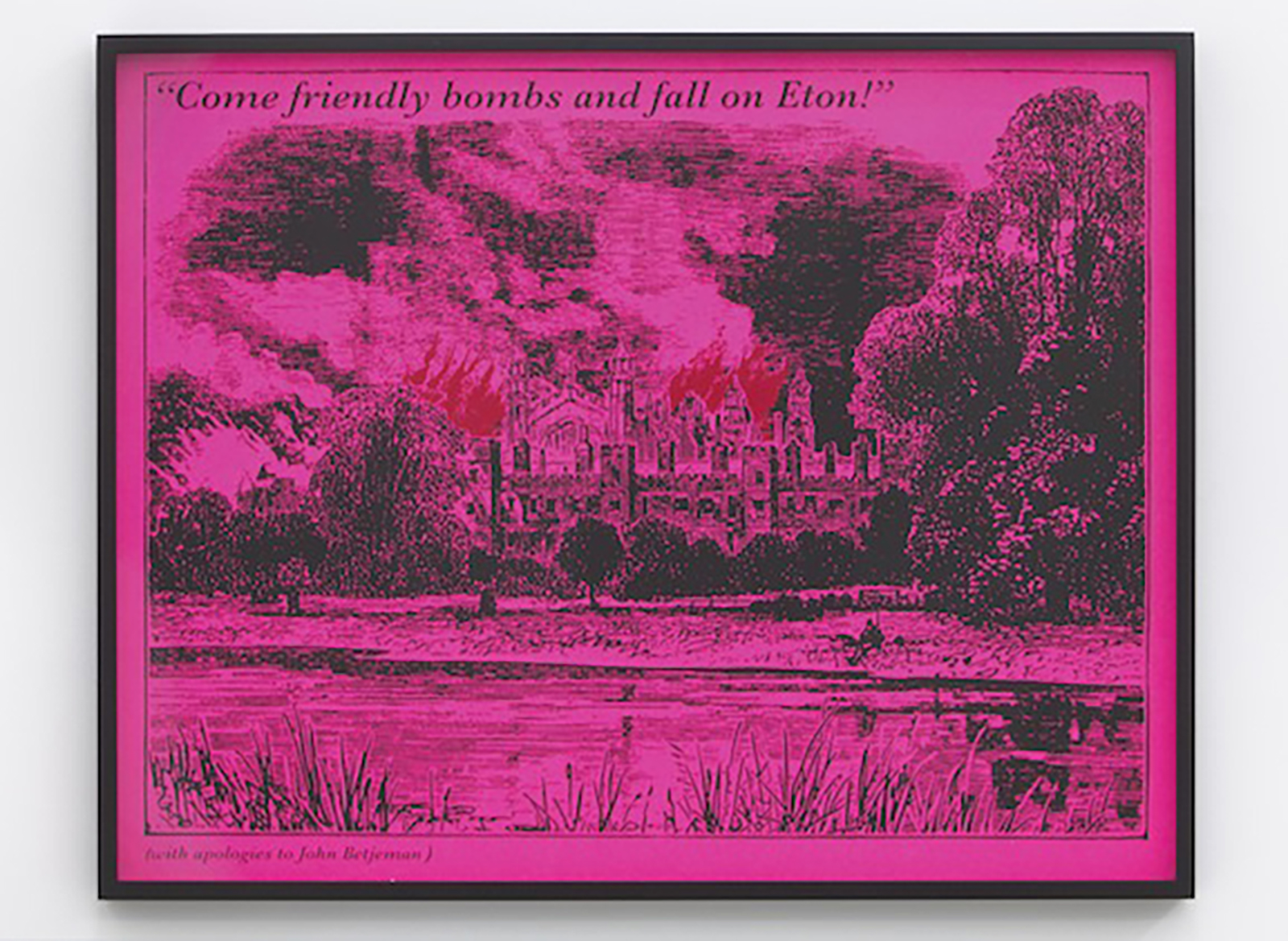

A top ten of Jeremy Deller posters might include the rave-era benevolence of ‘Bless This Acid House’, his Brexit-era ‘Welcome To The Shitshow’ (printed on a Union Jack), and a poster showing Stonehenge as if the monoliths were actually spelling out the word ‘vote’.

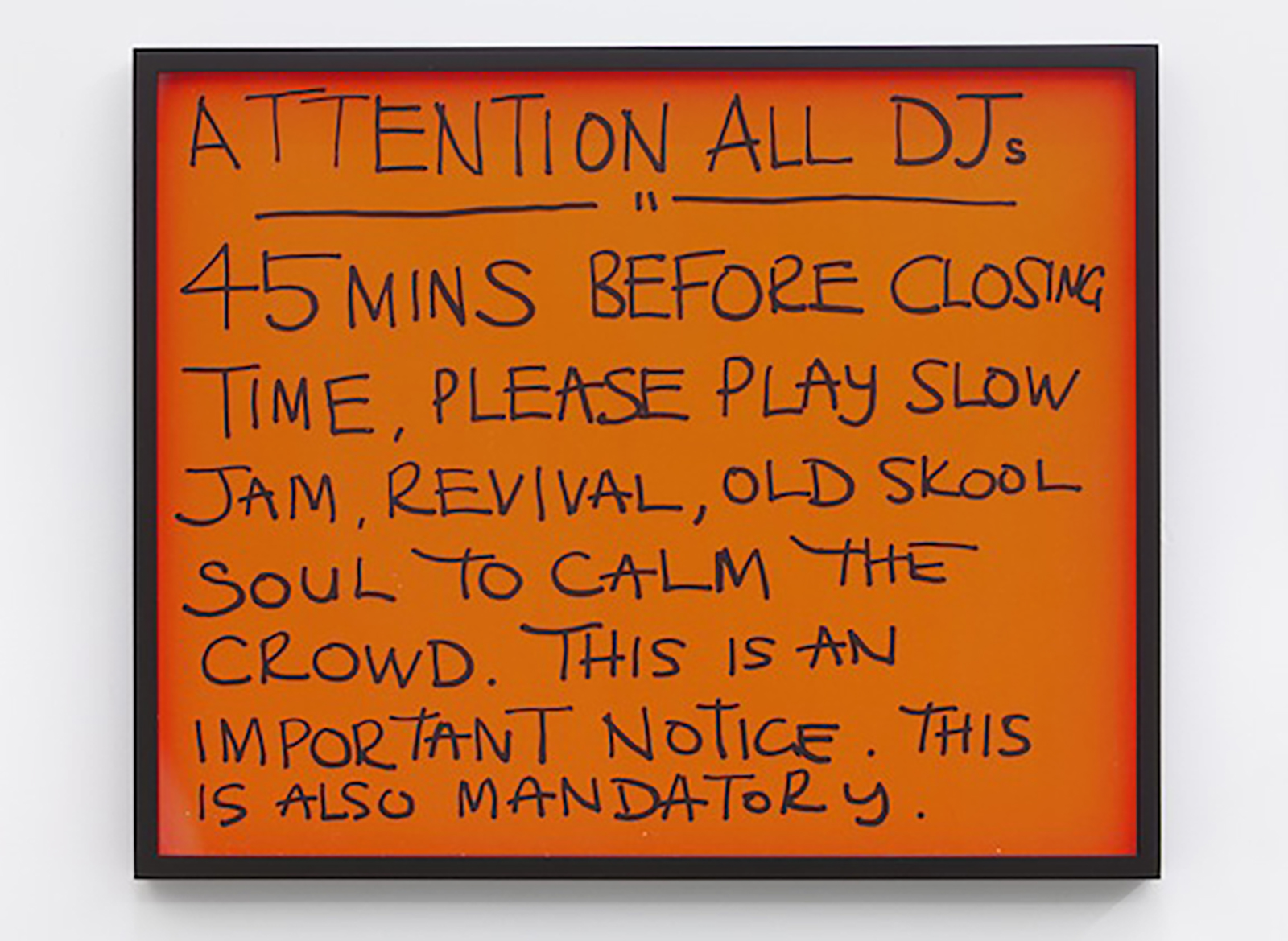

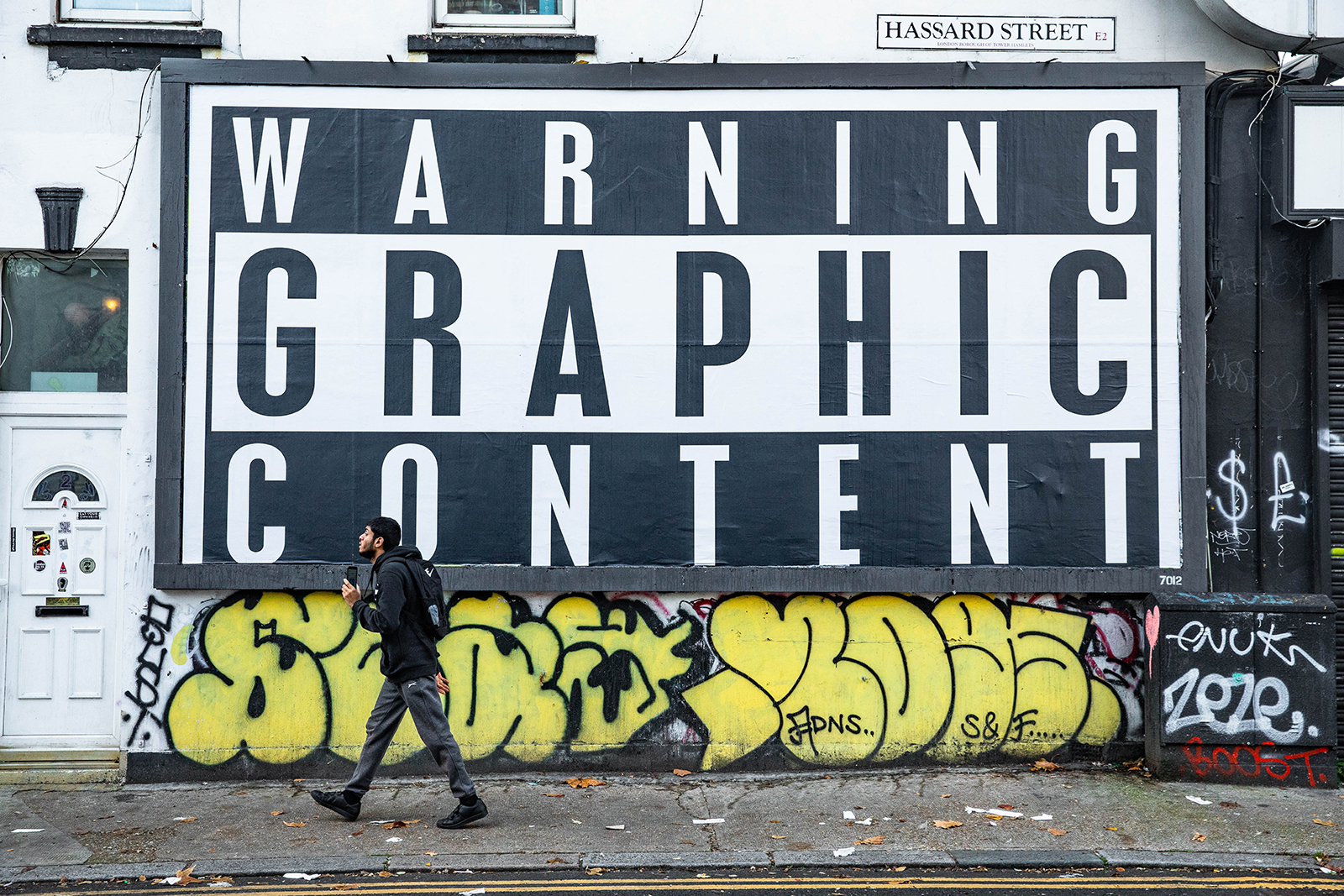

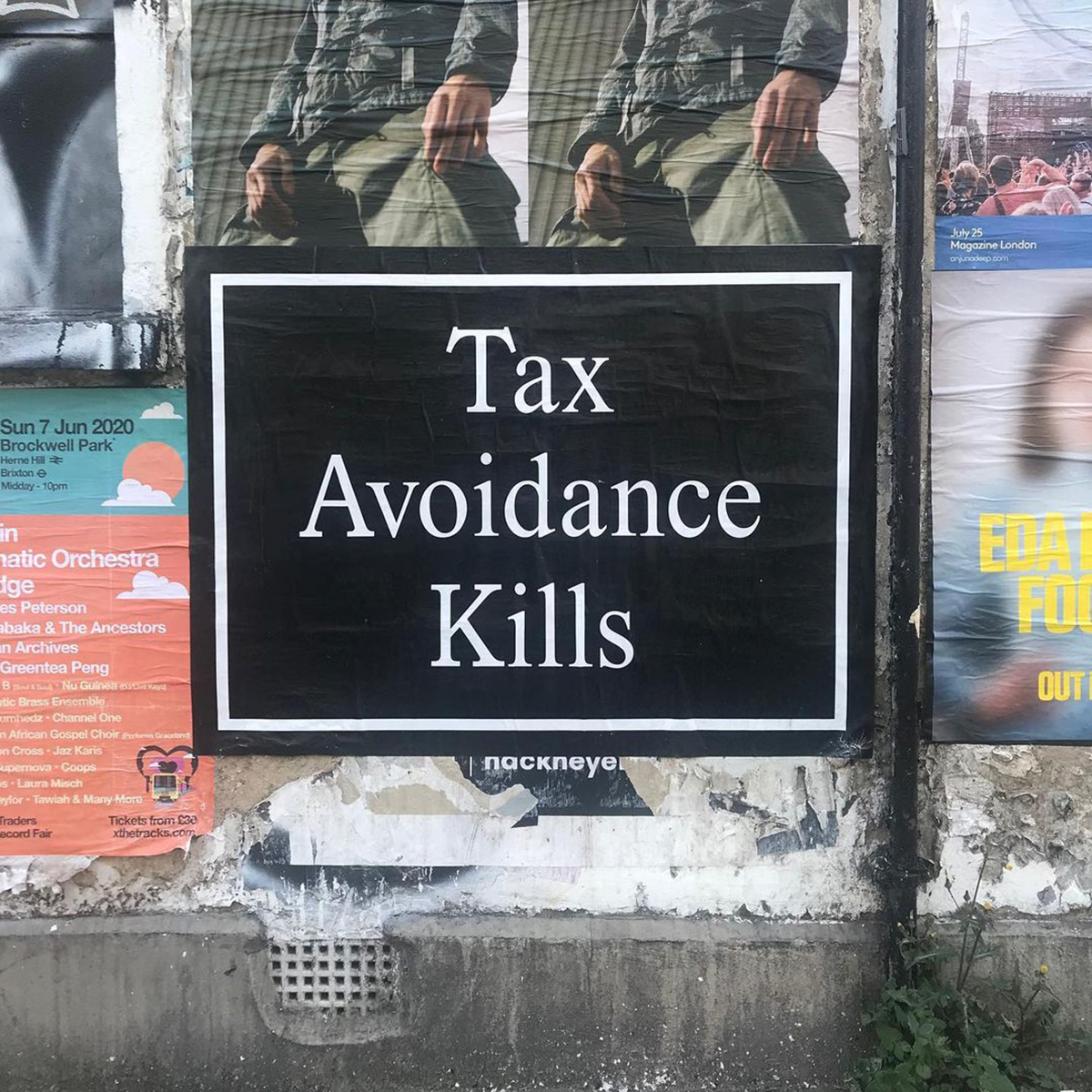

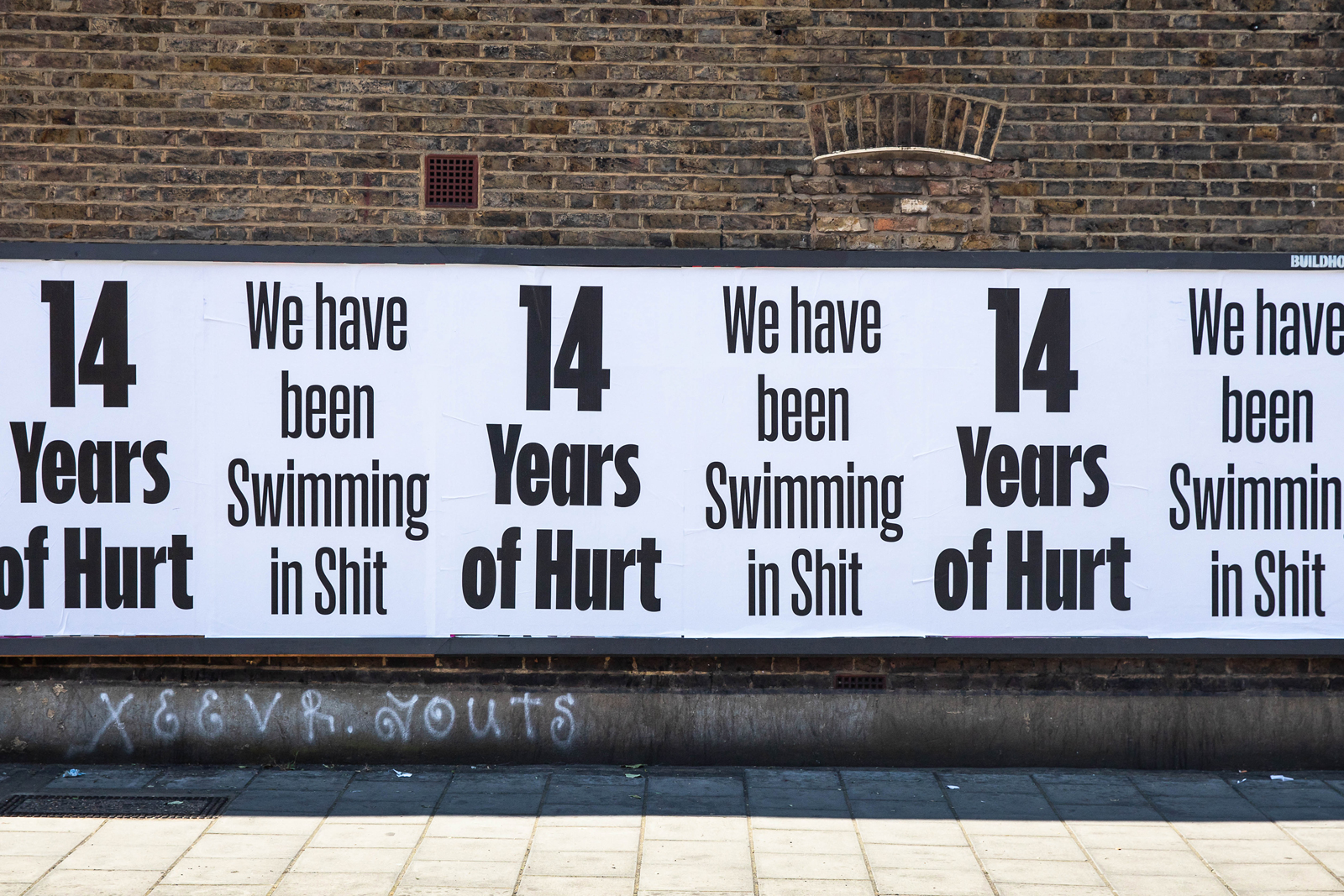

The 2024 General Election campaign sees two new Deller artworks hitting the streets, in collaboration with BUILDHOLLYWOOD. One states quite accurately ‘We Have Been Swimming In Shit’ with the other bearing the legend ‘14 Years Of Hurt’ (designed by Fraser Muggeridge). Posted up around the UK, they are he says, ‘self-explanatory’. ‘When you’re making a poster in the street you have to make it attention-grabbing, something easily and quickly legible, ’he says, adding that these two additions to the political poster archives are ‘insanely legible’.

The Euros influenced one of the posters. ‘Because the football’s on, I thought I’d wrestle it in. The design looks like the back of a football shirt, not that I’m a football fan. It’s obvious, maybe it’s too obvious, but everyone knows what it means, and what the 14 years refers to. It doesn’t need explaining’.

27.06.24

Words by