Your Space Or Mine

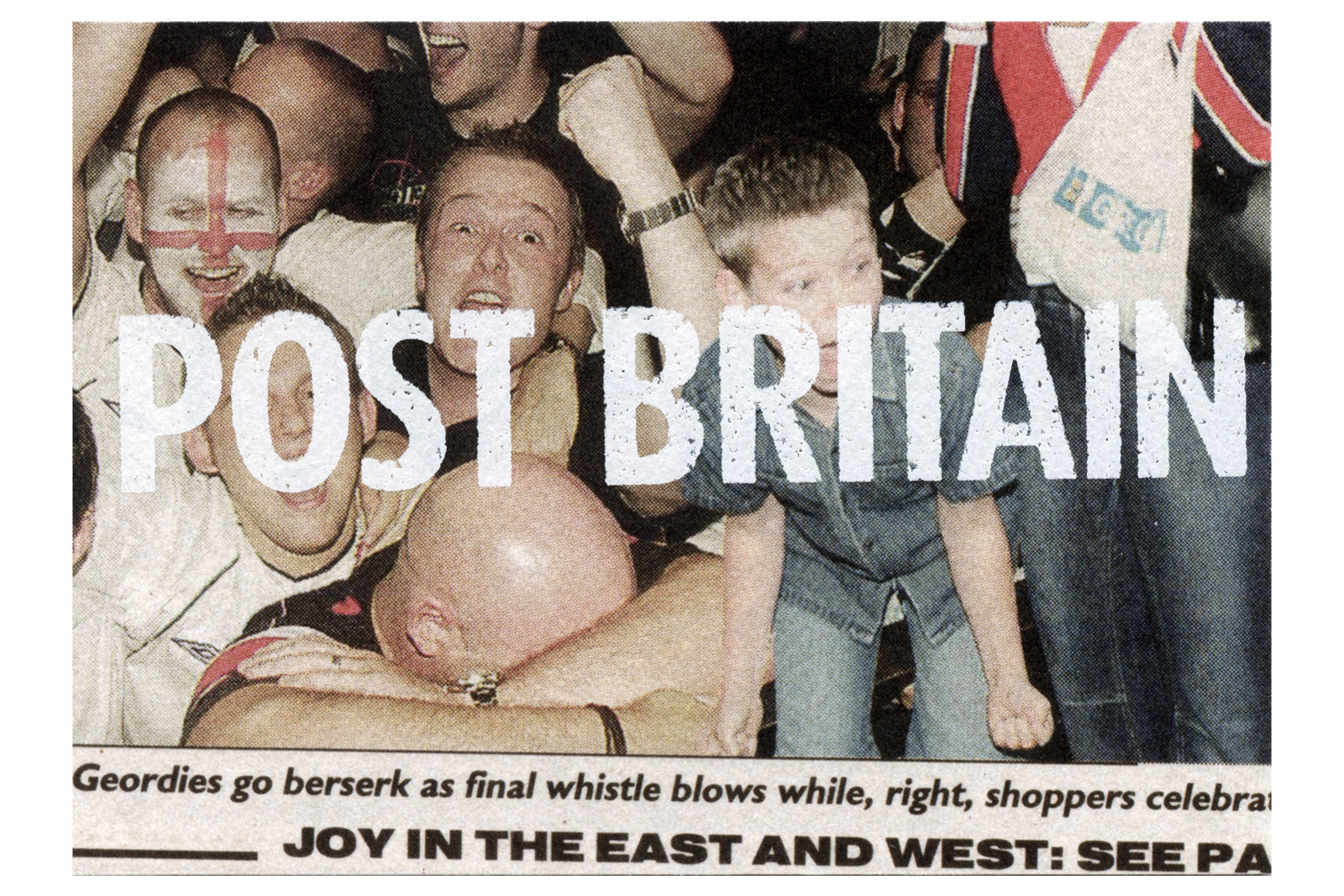

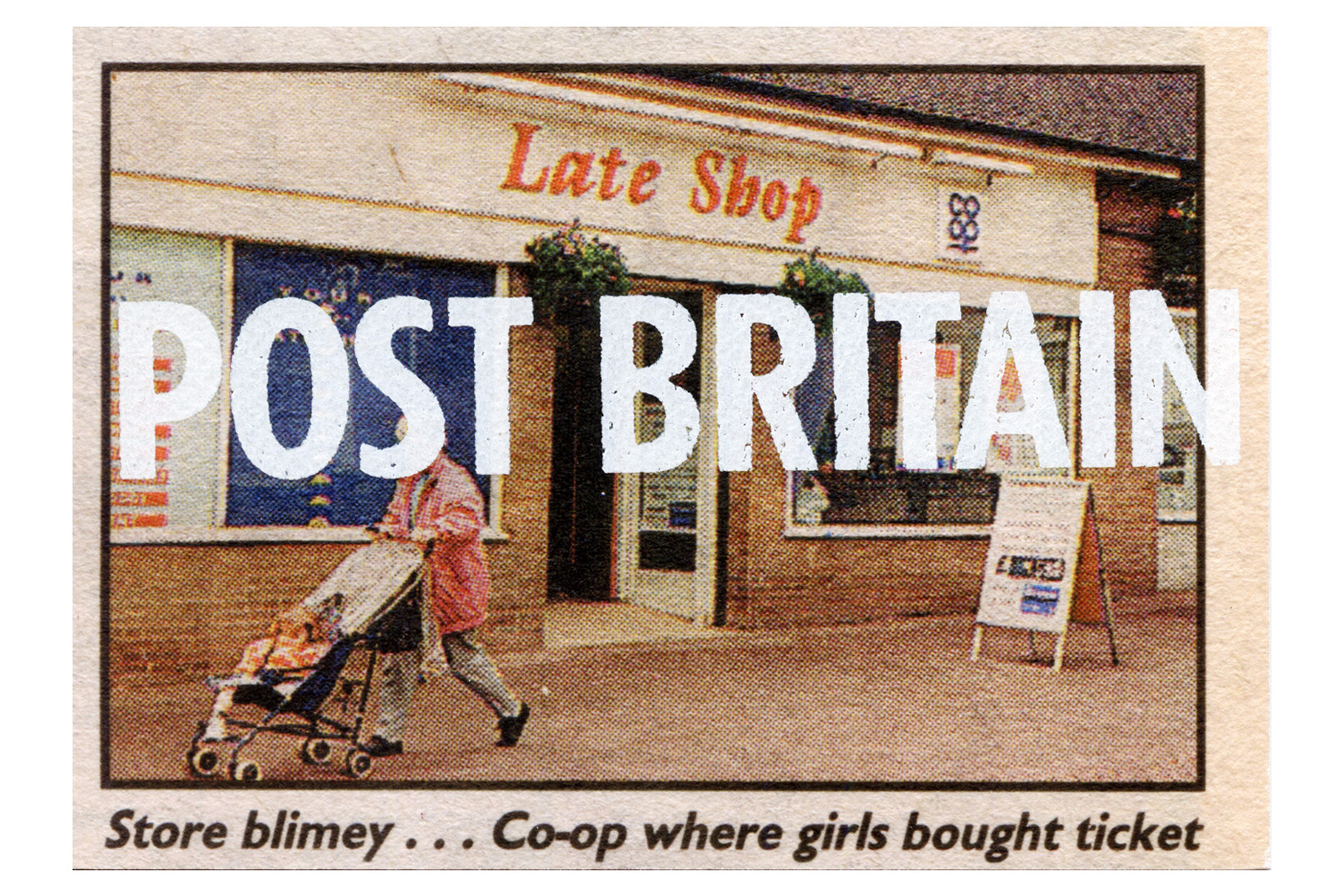

GOD SAVE THE TEAM: Artist Corbin Shaw takes on Euro 2024

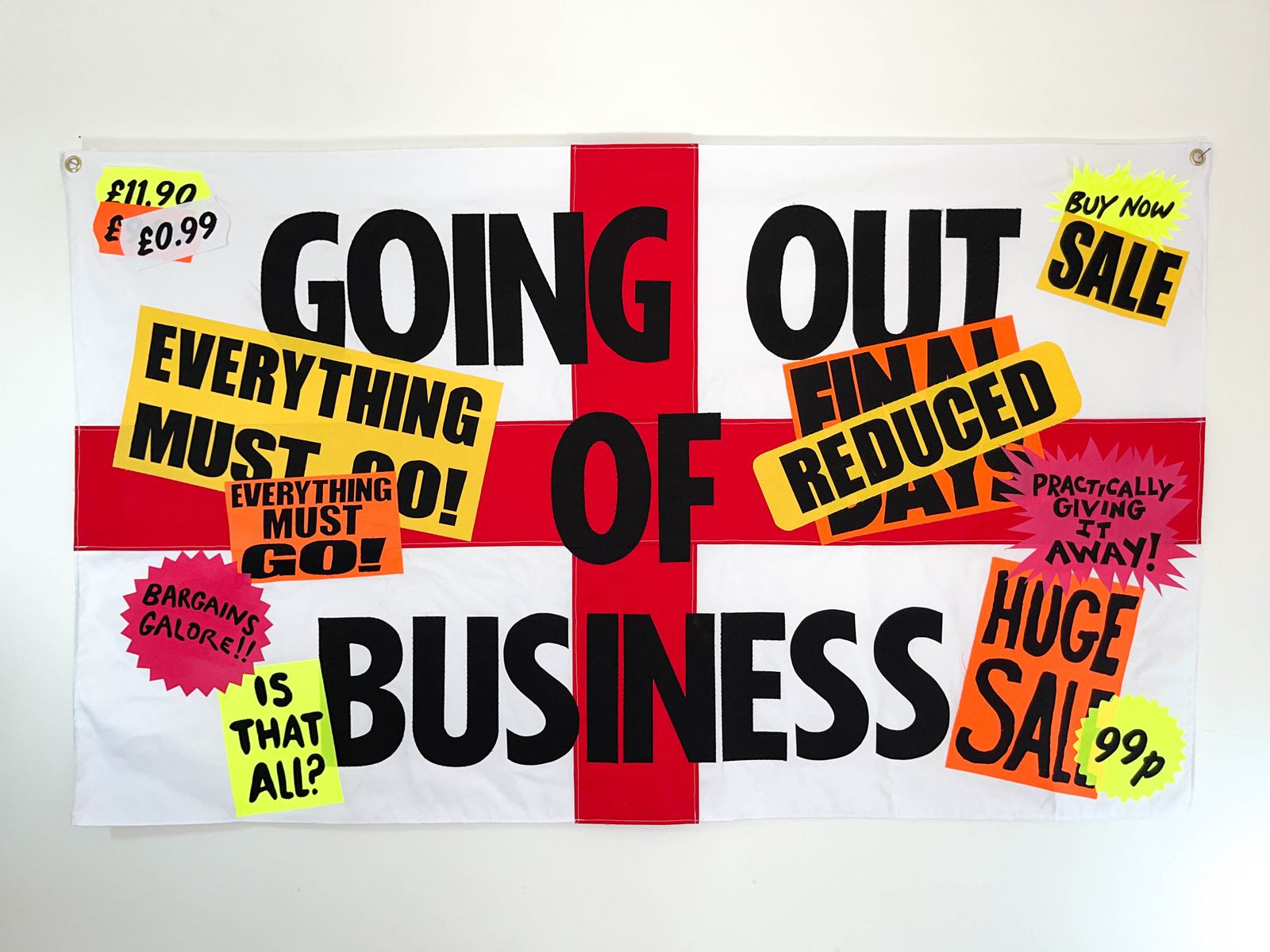

The cross of Saint George, a Turkish-born Roman soldier who died in Palestine, flutters above churches, dangles from pub ceilings and flaps from car windows across England.

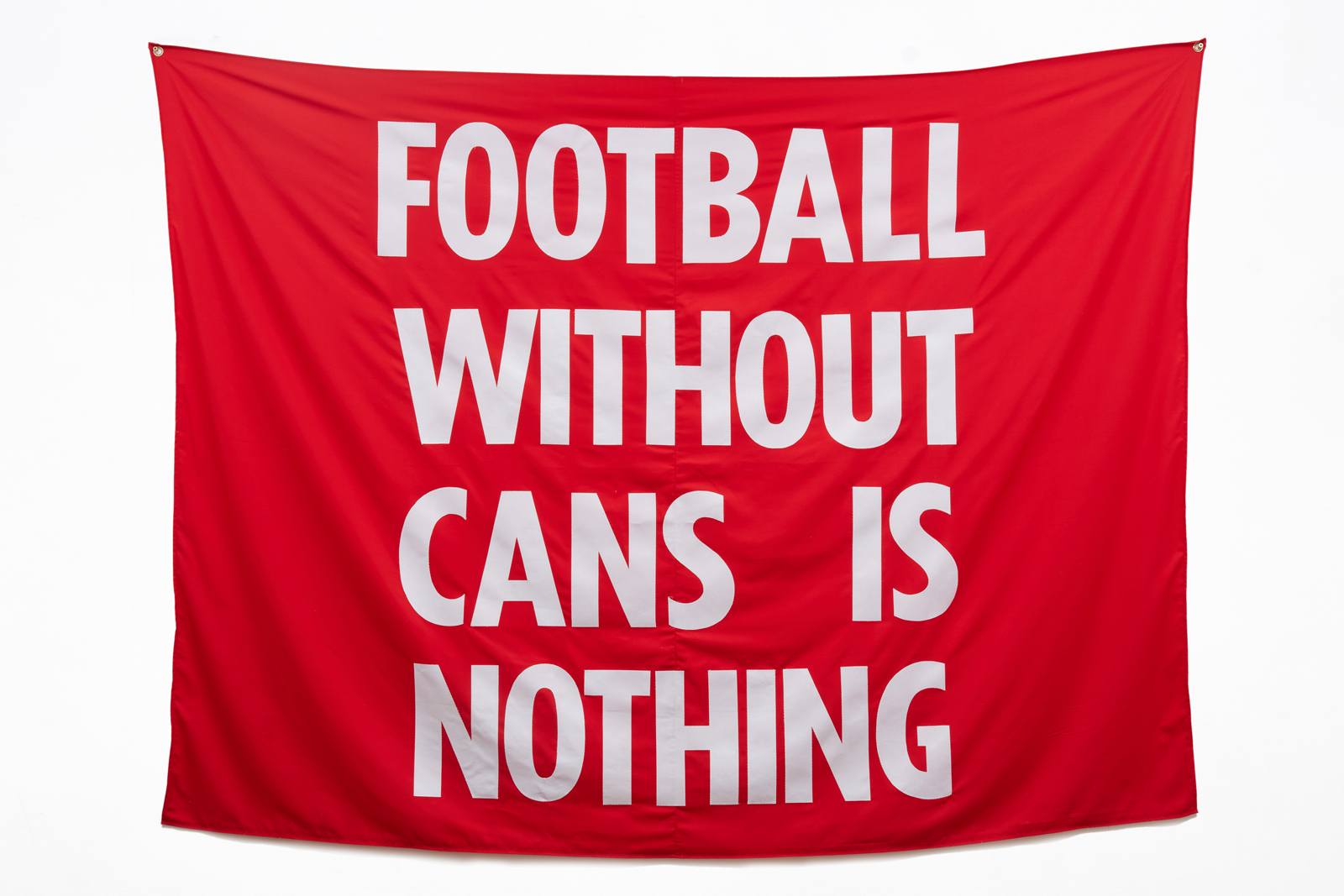

Its distance covered grows for a few weeks every year or so, depending on whether or not a team bearing Three Lions upon chests is participating in the latest major football tournament. This summer, as Gareth Southgate leads another squad of players to another major finals at Euro 2024, you can safely predict an increase in expected flags – and not just because patriotism-slash-nationalism tends to get turned up a notch.

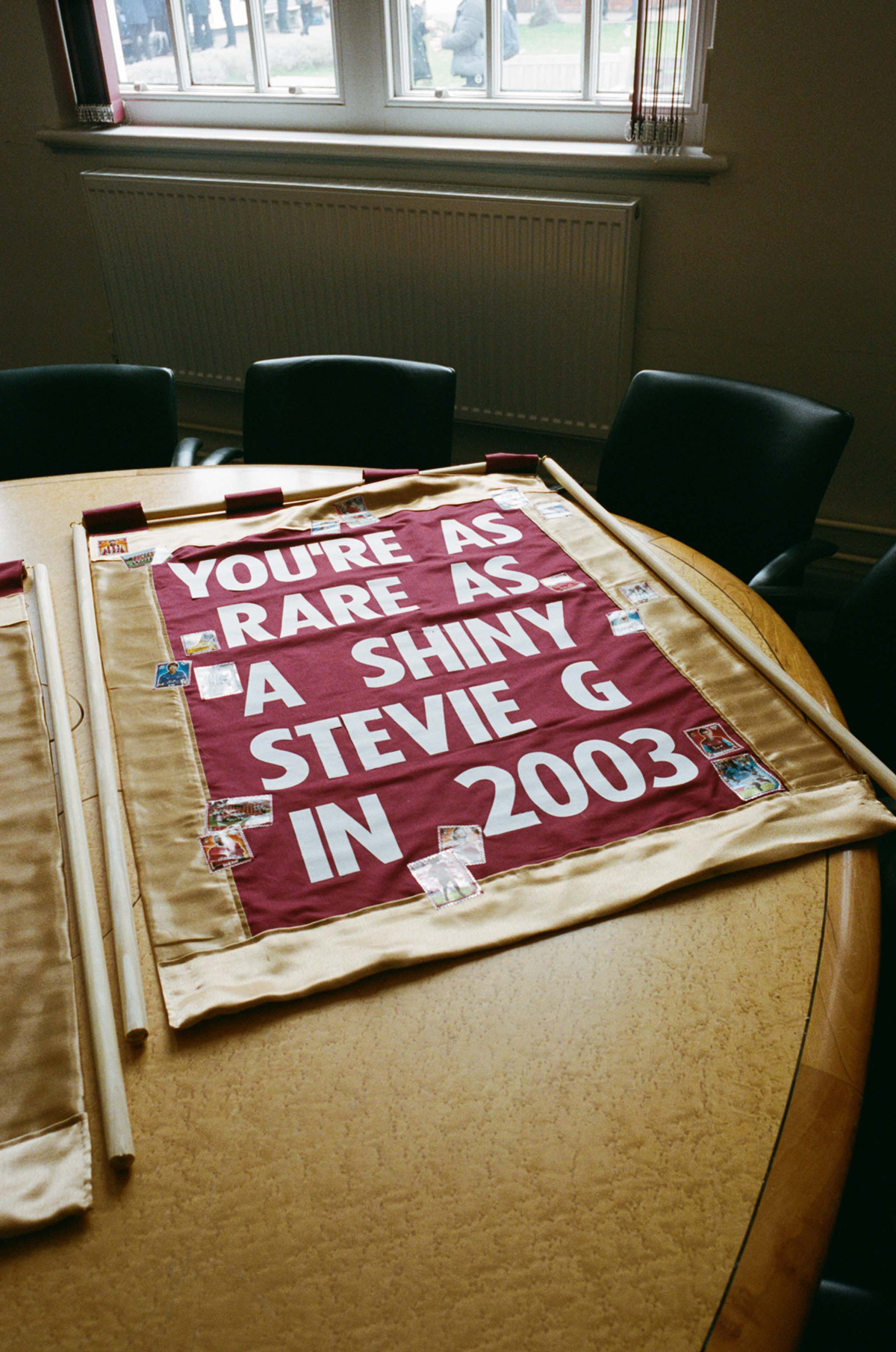

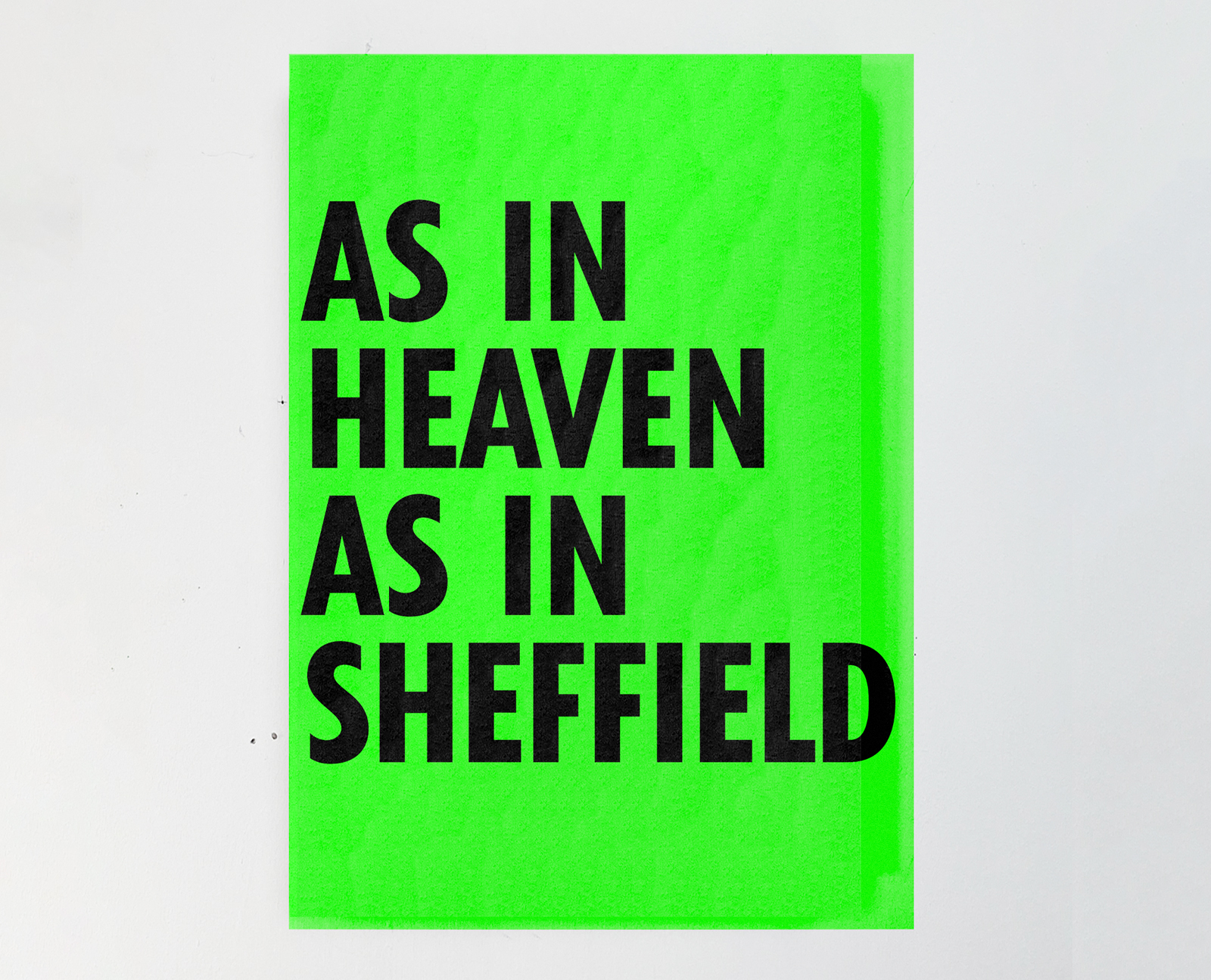

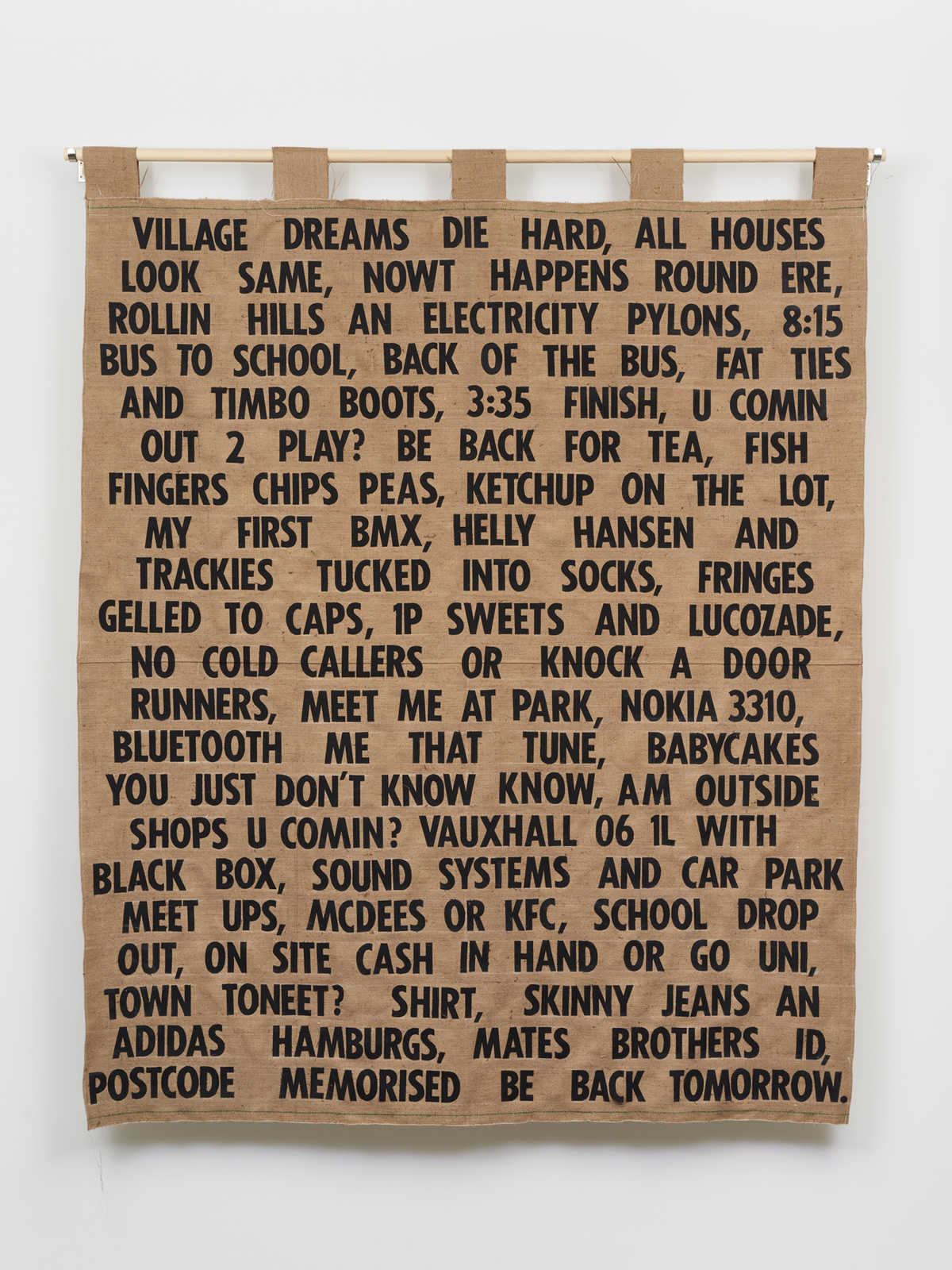

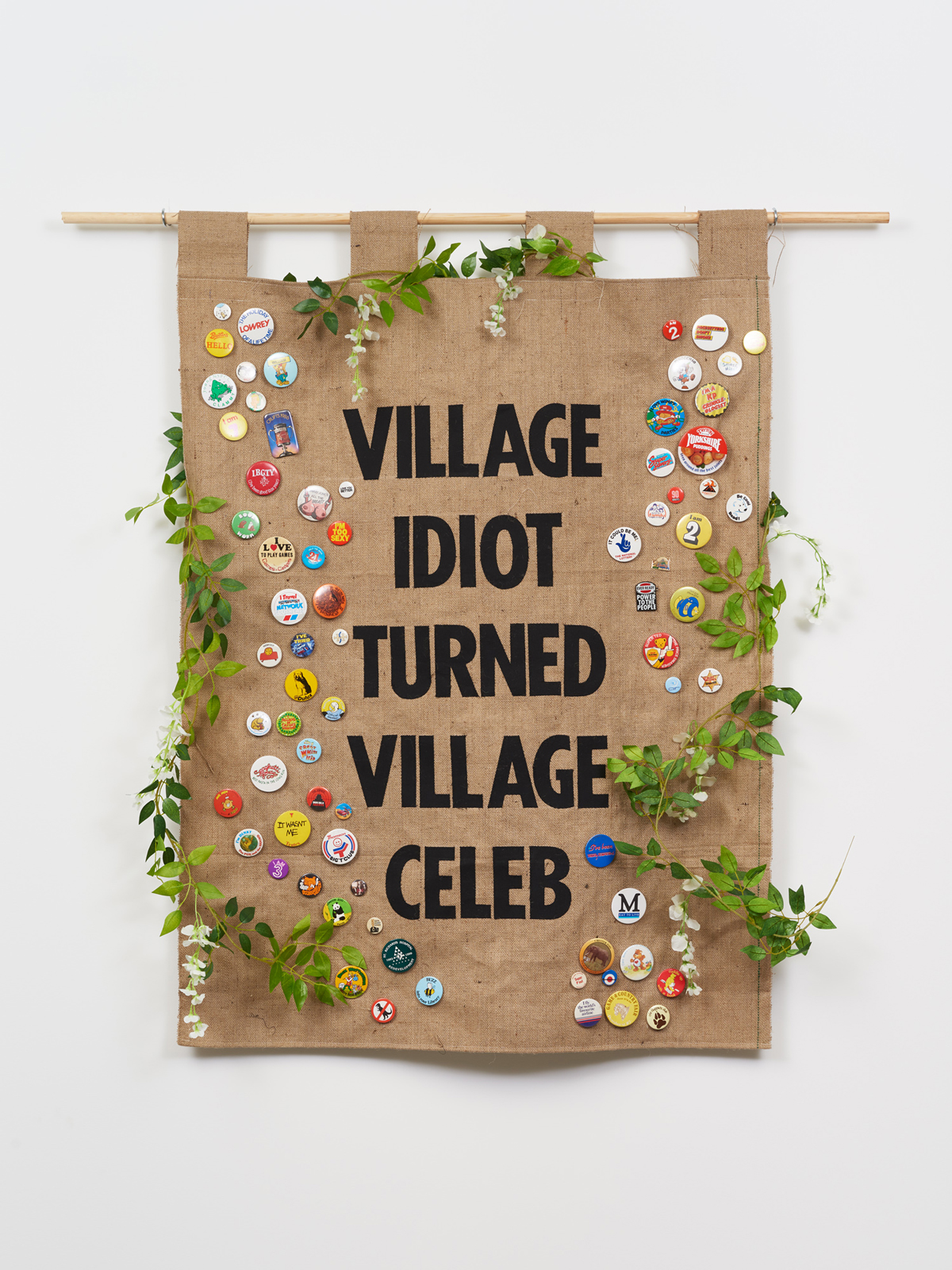

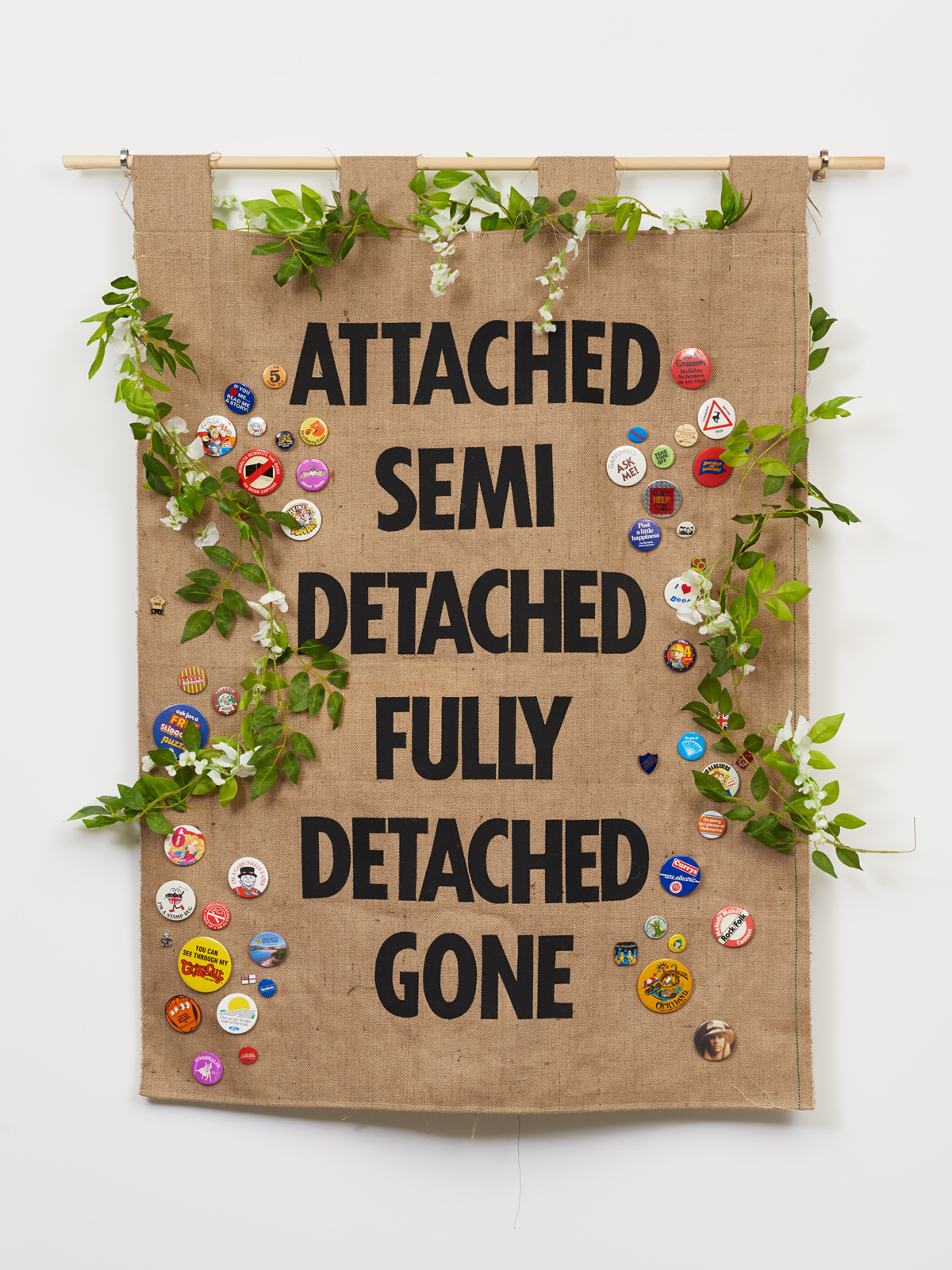

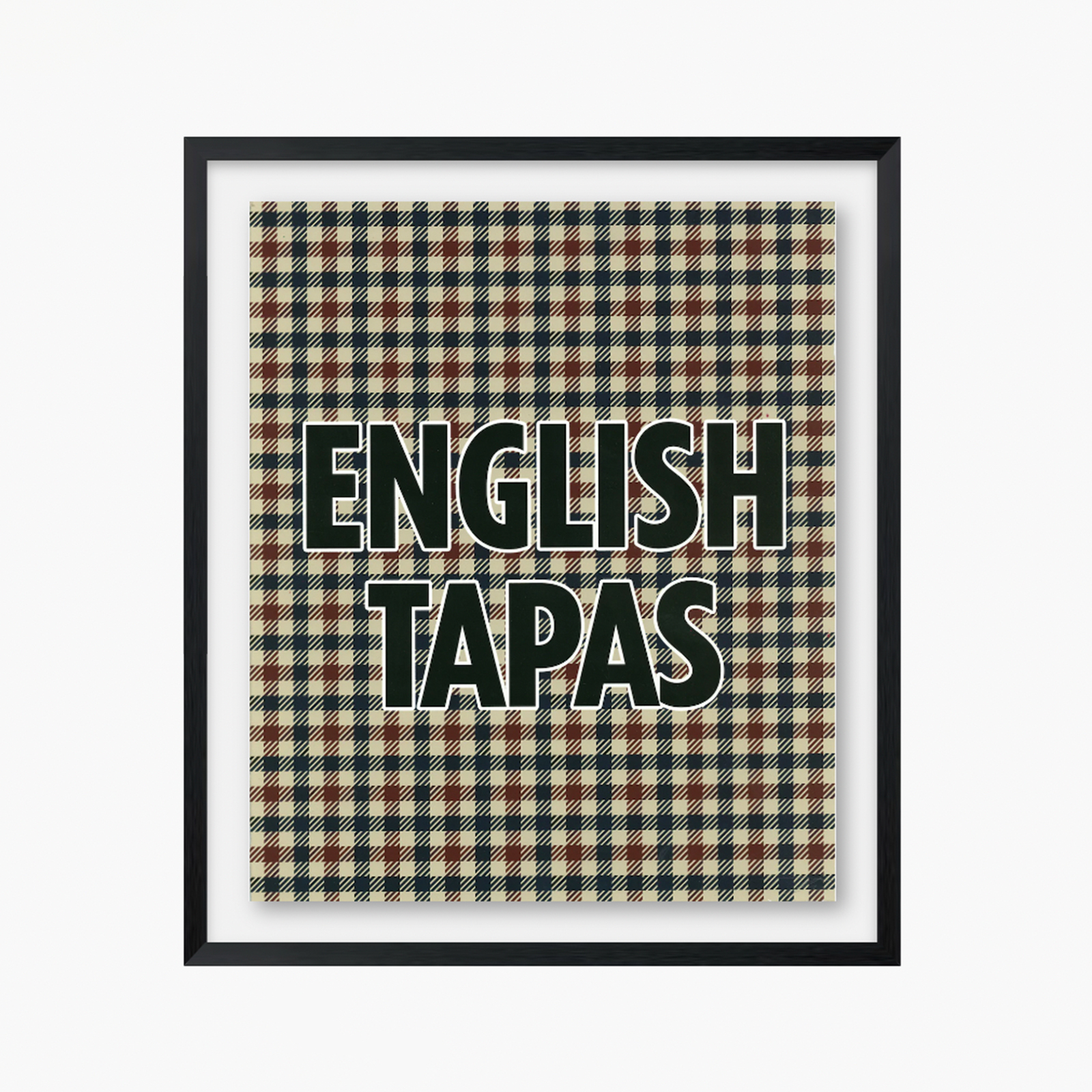

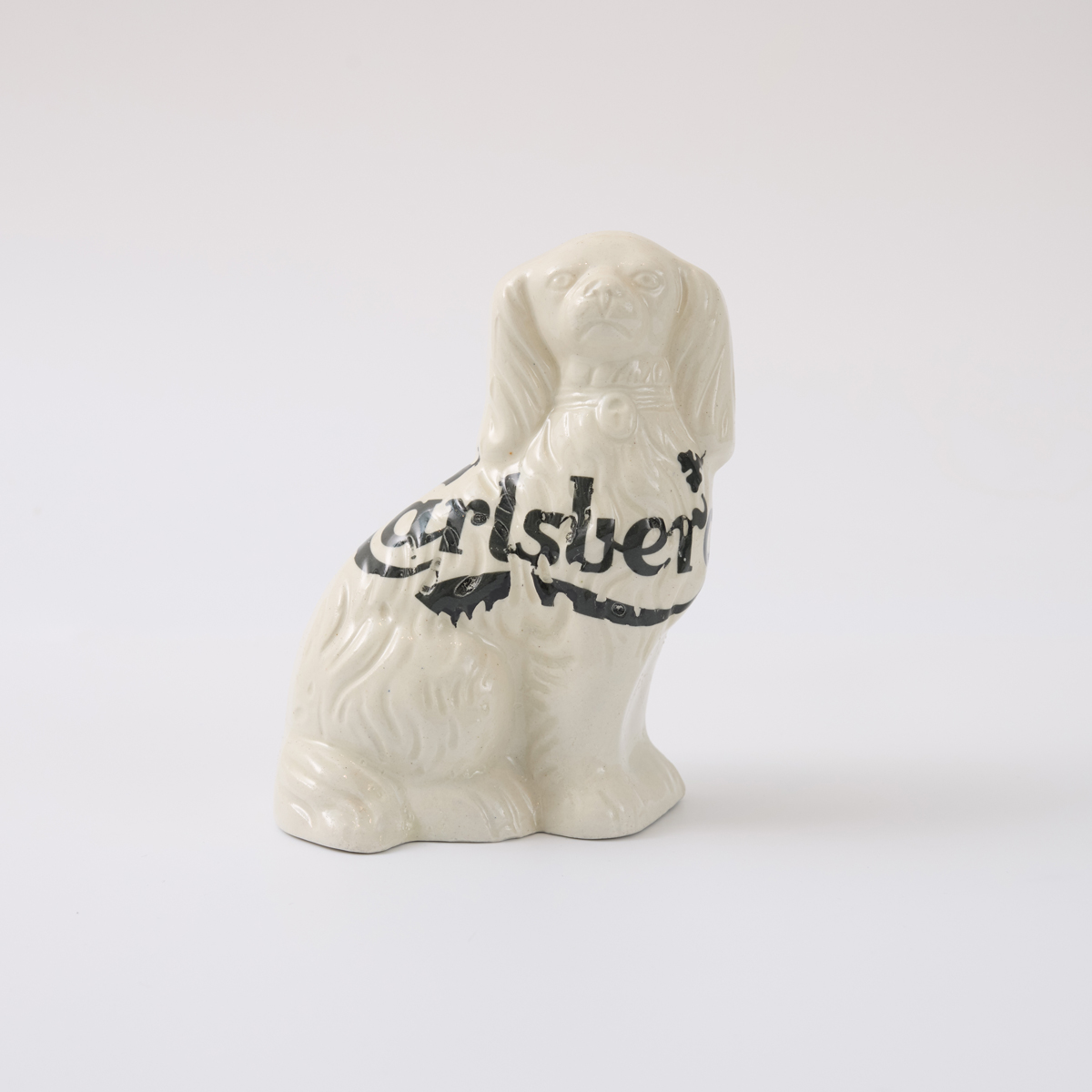

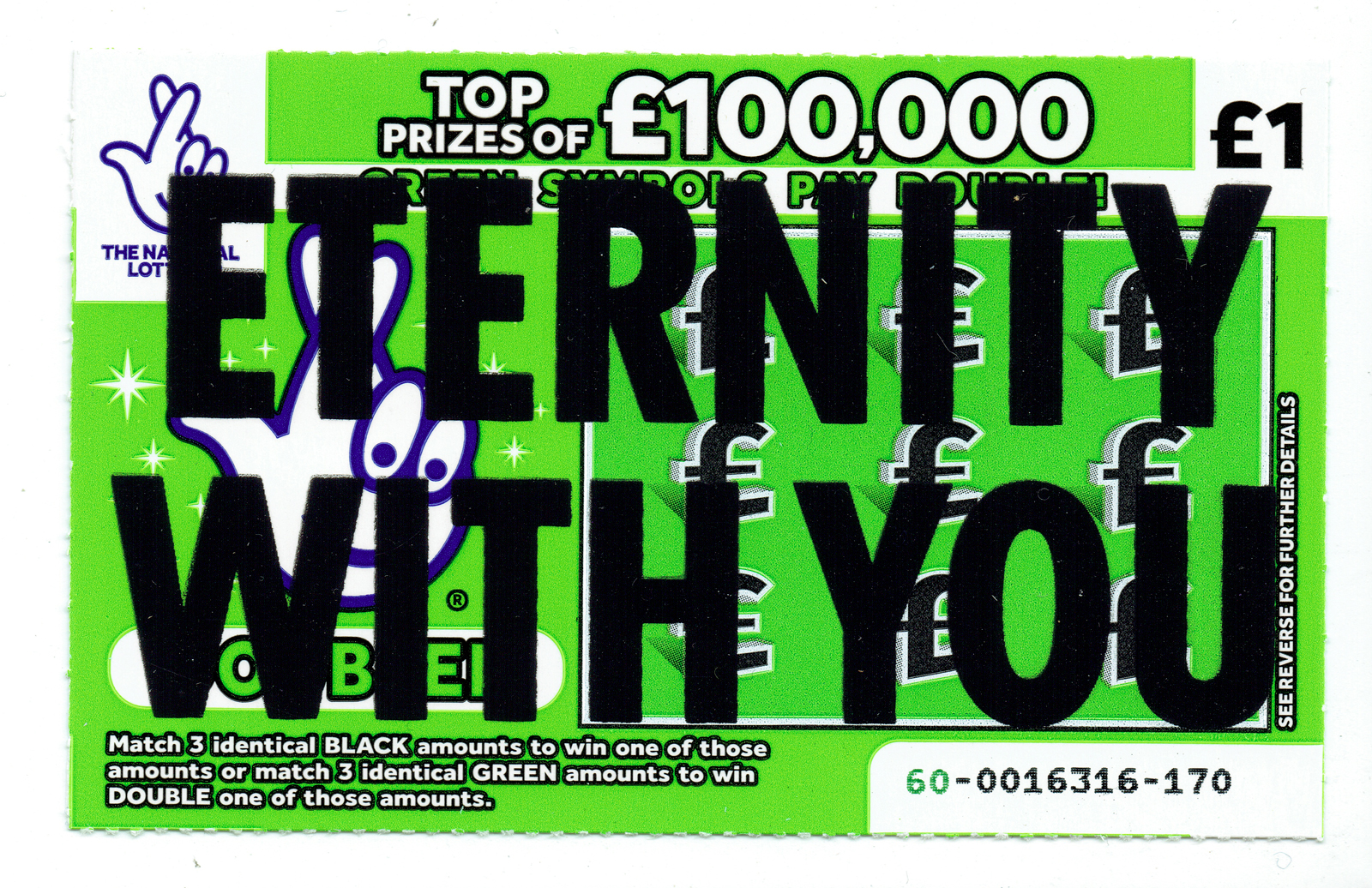

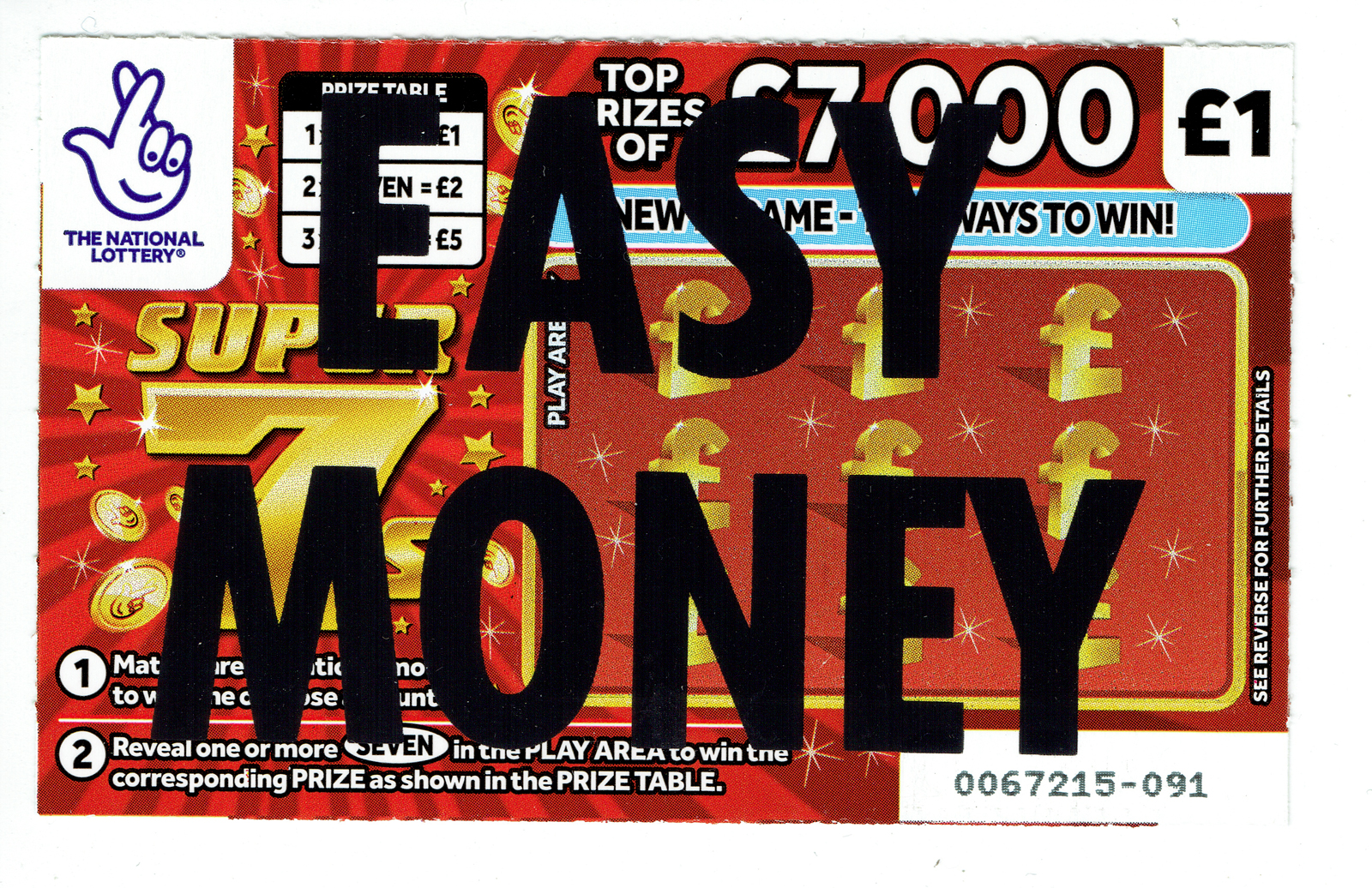

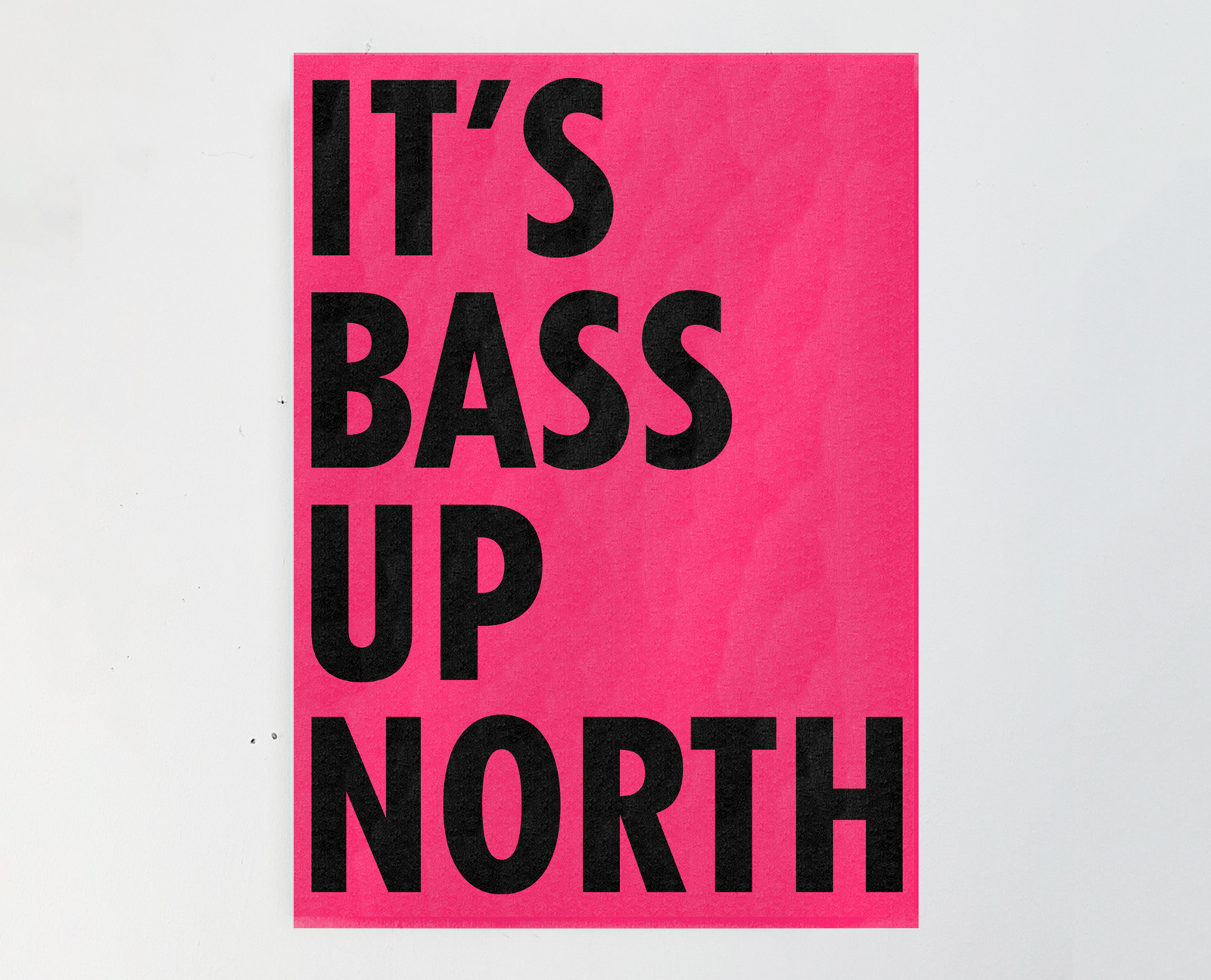

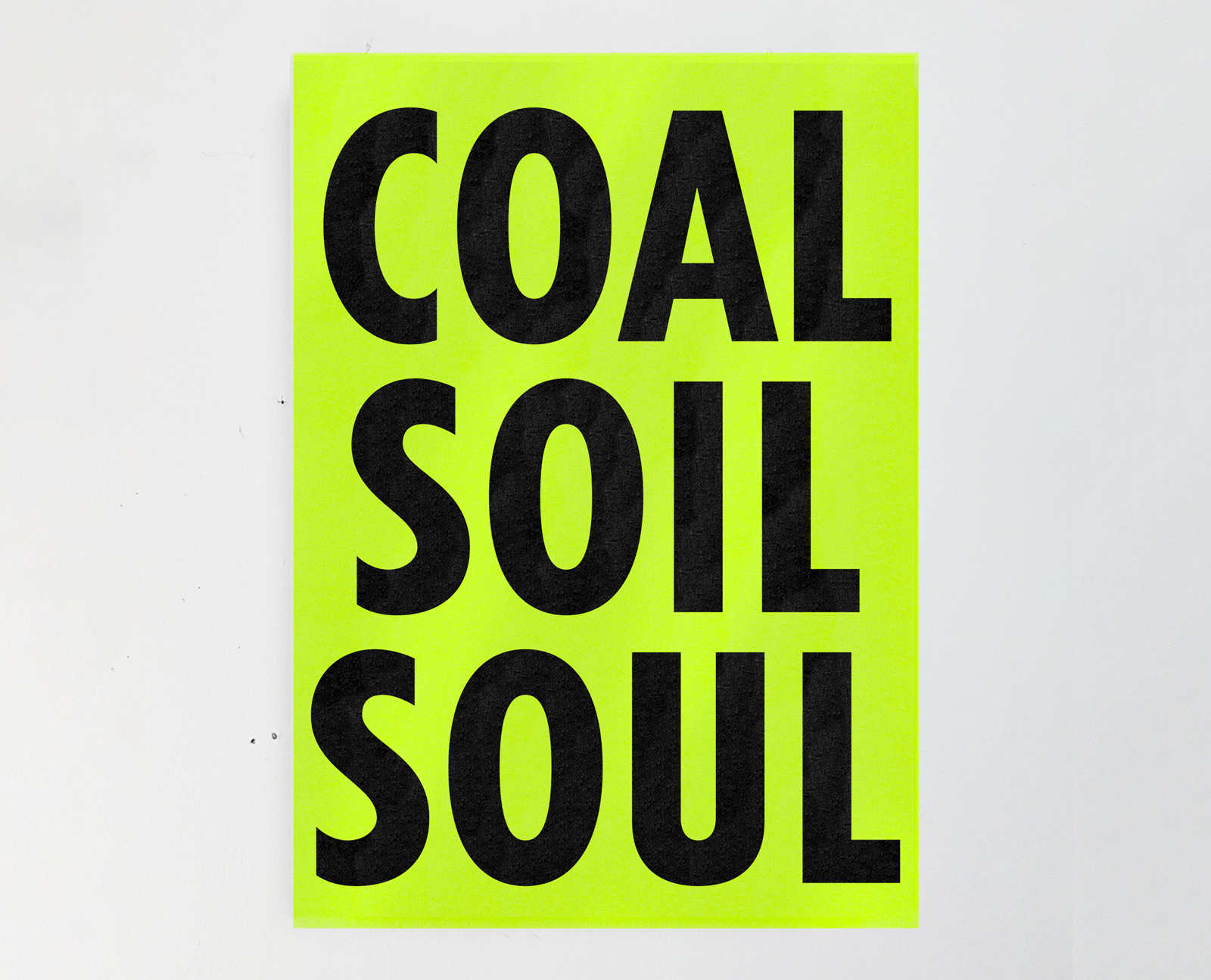

Sheffield-born artist Corbin Shaw has been using England flags as his canvas for a while now, and with the help of BUILDHOLLYWOOD’s Your Space Or Mine project and their billboards, his take on St George’s Cross will adorn city streets up and down the nation.

Its use is not about reclaiming the flag, but rather using it as a “Trojan Horse” to deliver messages about national identity and masculinity. “It’s quite abrasive,” he says, chatting to us during a trip to Marseilles – a city that felt the sharp end of this cross during the World Cup in 1998. “It’s got a lot of history in colonialism and right-wing nationalism and I wanted to use it, overt that and juxtapose it.”

15.06.24

Words by

STAN-DICKINSON, CIRCLE-ZERO-EIGHT

STAN-DICKINSON, CIRCLE-ZERO-EIGHT

NIA-ARCHIVES3

NIA-ARCHIVES3

CIRCLE-ZERO-EIGHT

CIRCLE-ZERO-EIGHT

NIA-ARCHIVES1

NIA-ARCHIVES1