Contrary to De Quincey the psychogeography writer Iain Sinclair – who preferred the term ‘psychotic geography’ to describe his work – counselled against walking under the influence. He thought you could train yourself to be hyper-sensitive to the effects of geographical location on behaviours and emotions. His walking resulted in blends of fiction, documentary, poetry, accounts of contemporary experiences and concerns re. the city as well as recording its historic and psychic reverberations. Can you share some of the material outcomes that result from your walks?

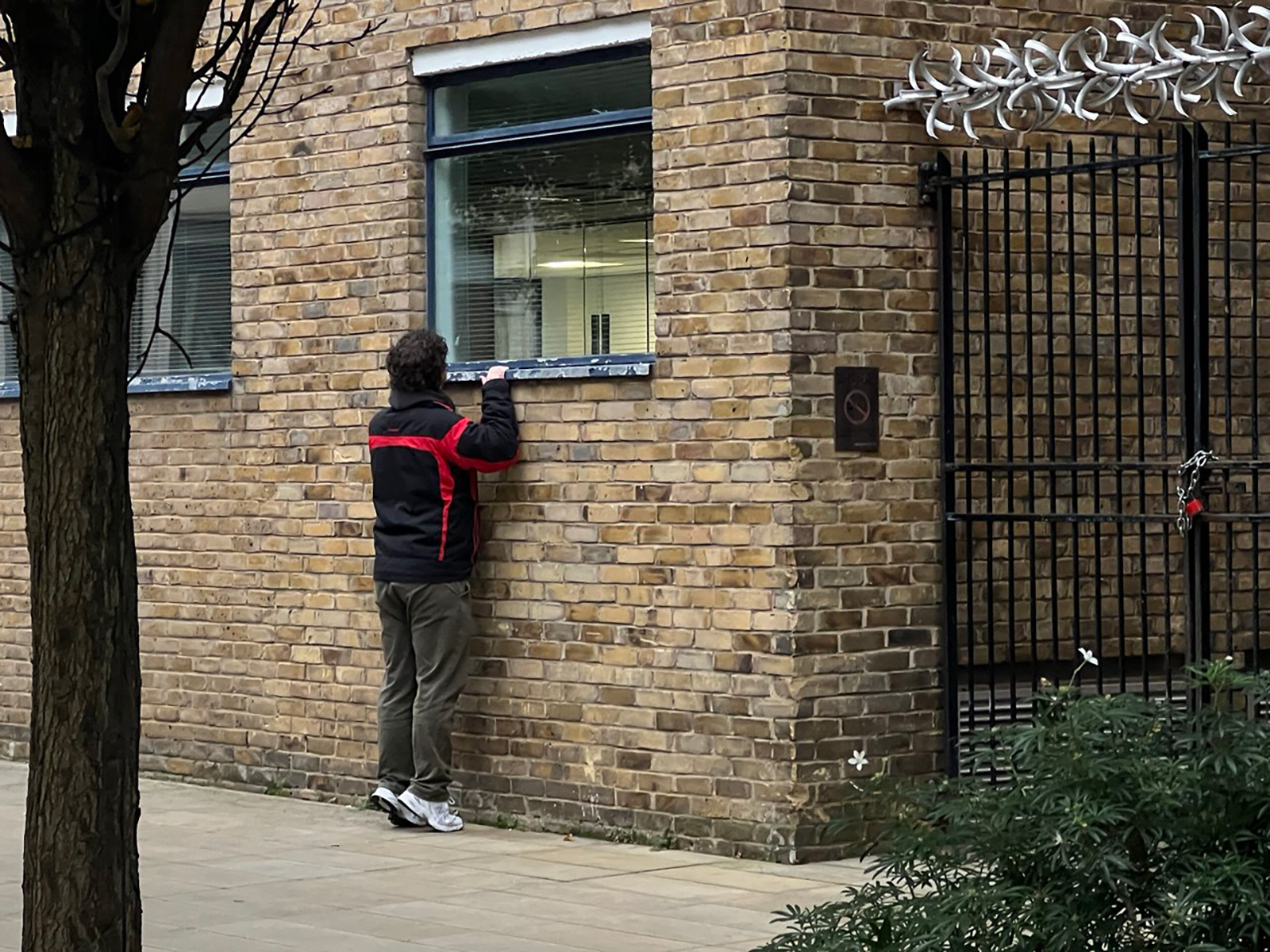

Yes, and I’d like to pick up on this phrase ‘poetic’, I quite often get this response. And I take this phrase from one of my teachers Franko B who says, ‘the personal is political’, for me that really works. The walks afford this personal and poetic space but then it always has a political element as well. What really impresses me is that sometimes the smaller the shift, the bigger the effect. So, it’s not about big gestures, or big sparkling moves, it’s not about like a carnival, you know, like us dressing up and walking somewhere. It can be just tiny gestures like let’s walk this street only looking down, never looking up. It’s a tiny shift that’s almost invisible from other peoples’ point of view. But the shift in perception as to how you see the city and how you see yourself reflected in the city can sometimes be so huge.

Why I’m interested in this specifically is – maybe on our series of walks we’re a bit more visible because we’re in a bigger group – but in most of my work the actual action of us doing something is usually very invisible. For me this is an important element because it doesn’t stand out too much to passersby, and it doesn’t ask too much from the participant because again not everyone is ready to be so visible. For me being able to be invisible is an important part of it, an important access moment. I used to make a lot of audio walks because I was interested in this idea that you’re just looking like someone wearing headphones but you’re on a completely different journey in the city.

Regarding material outcomes, there’s a tension in my work because, of course, I come from this radical tradition of performance art where I like the fact that there is almost nothing left, nothing’s happening except this moment of us walking through a place, that immediate encounter. I used to do mostly one-to-one works walks, which is even more intimate. But, of course, the way the art world operates there’s a need for documentation. What’s changed is me starting to have a bit more resources because, as I said, for me walking began from the practical position of not having access to resources because I come from both like a really working class family but also the family that was affected by fall of Soviet Union and economic migration. So, there’s definitely a financial element to it, where I was like, okay, I don’t have anything, but I can do everything with nothing.

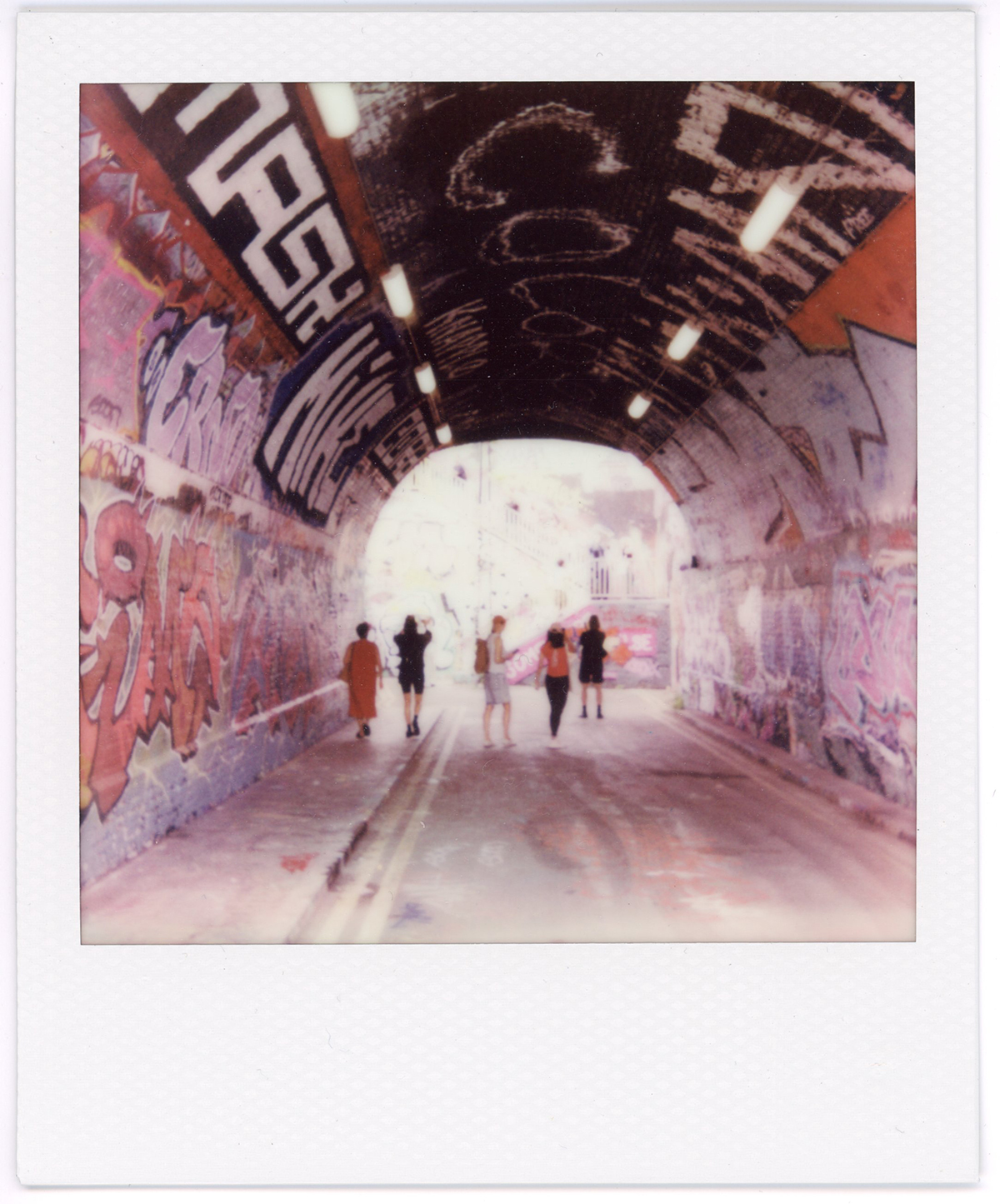

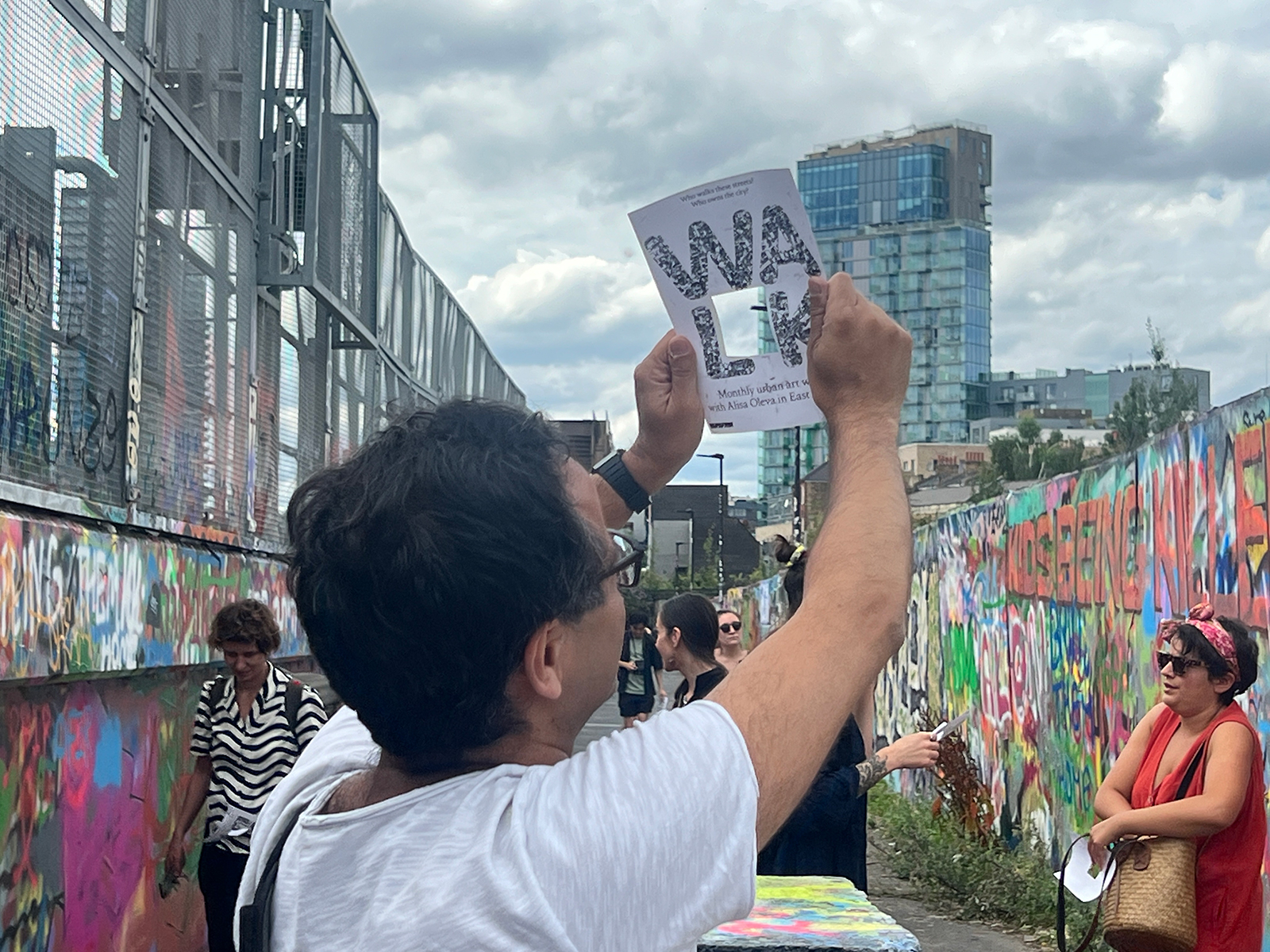

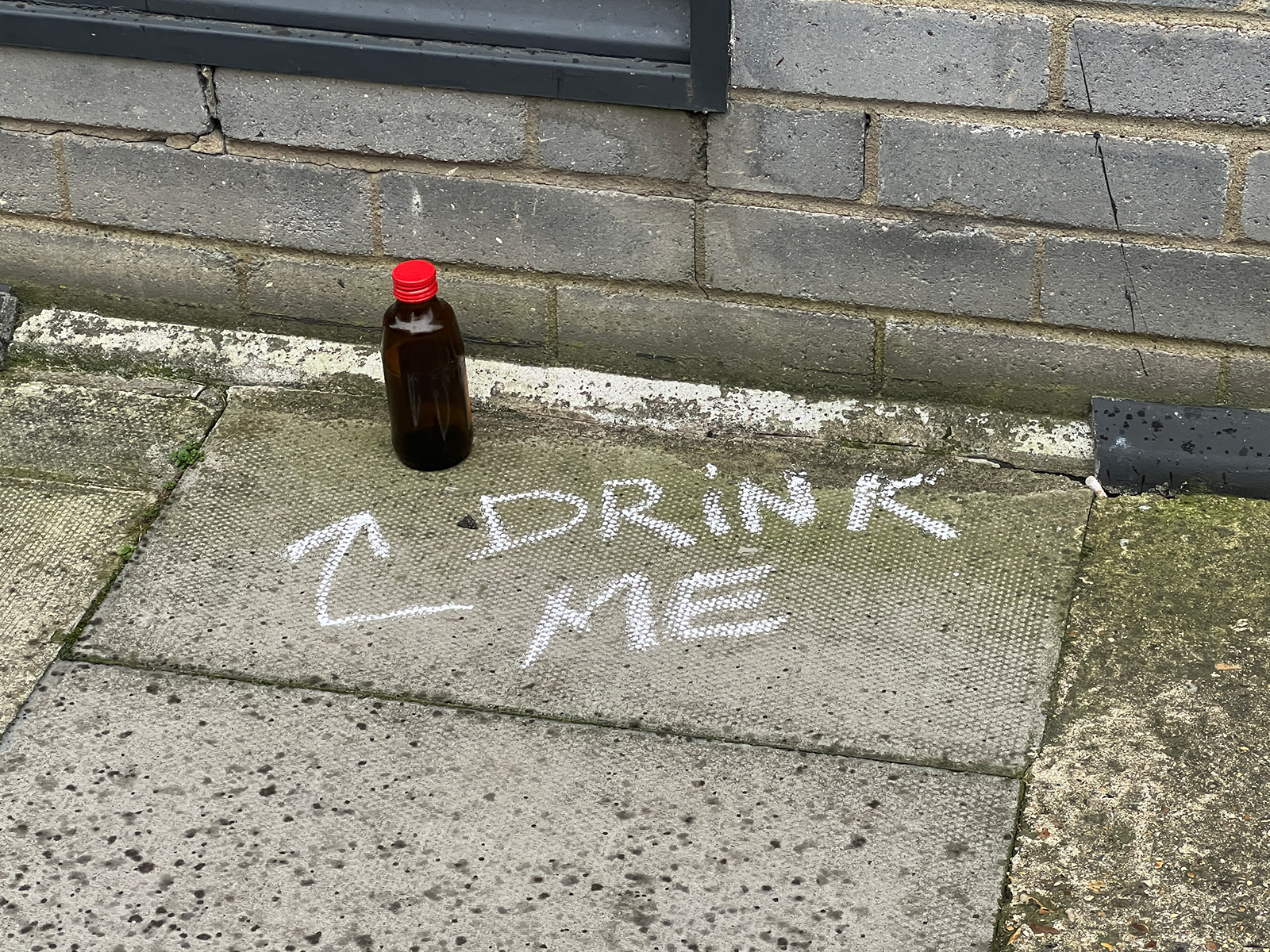

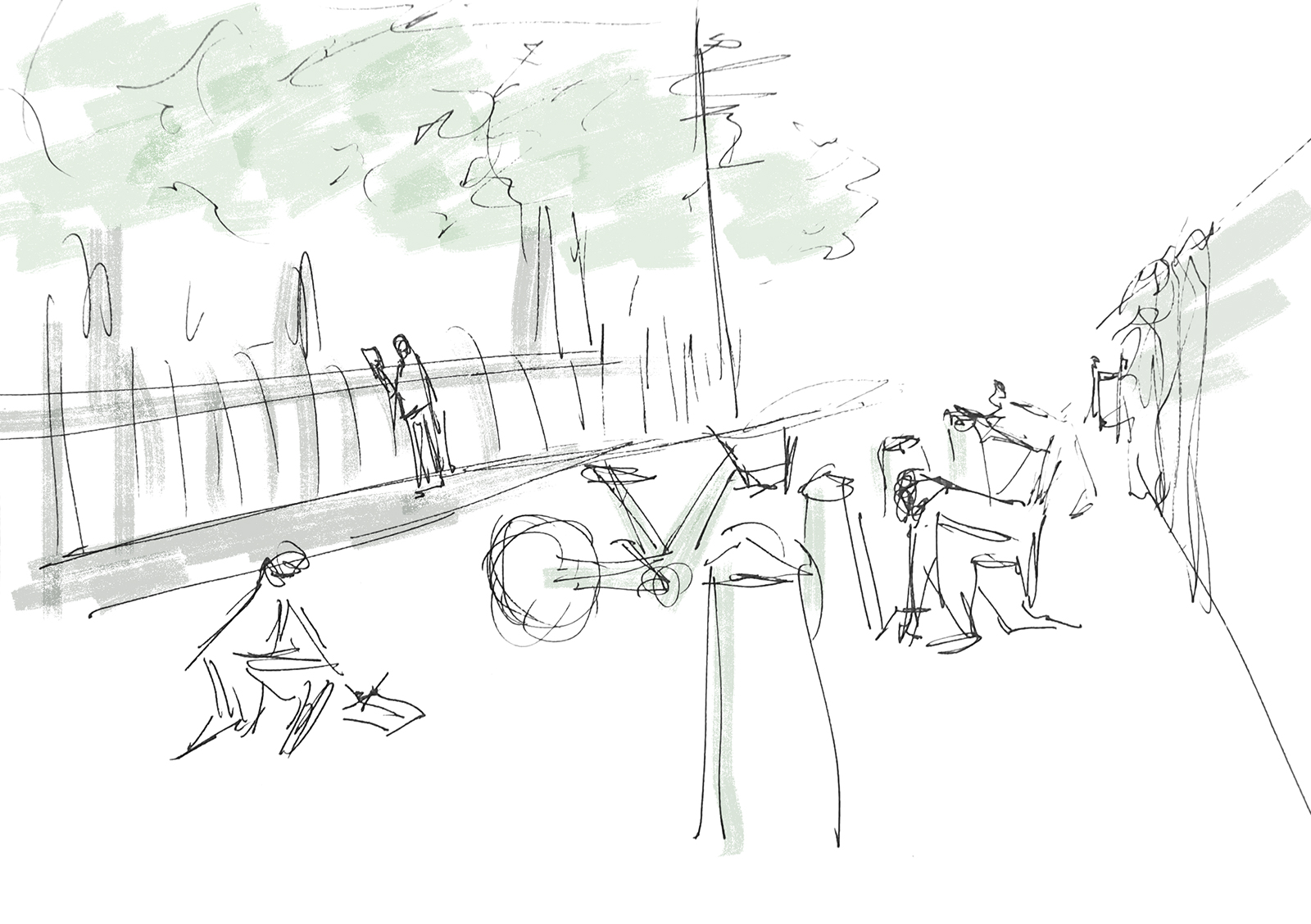

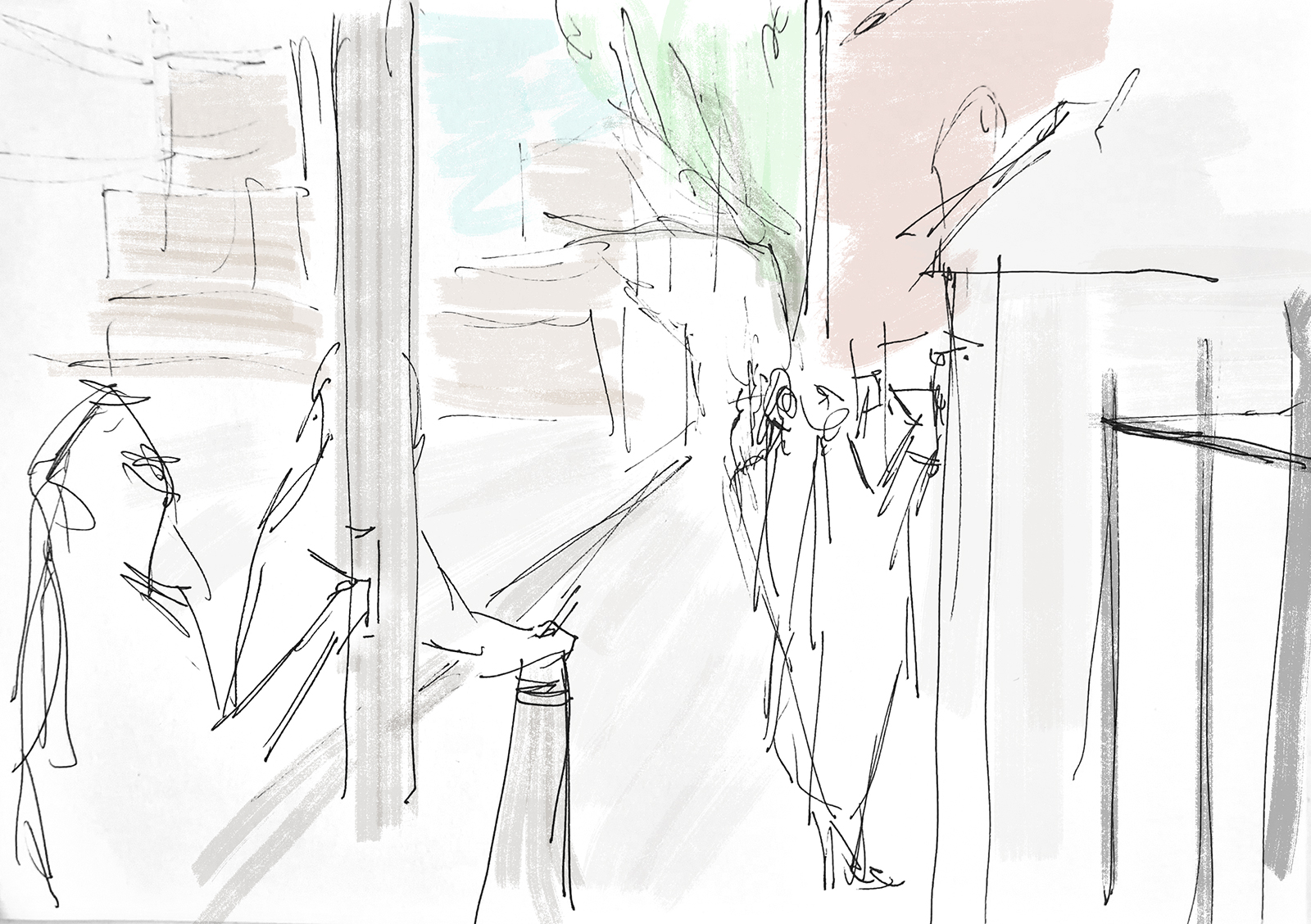

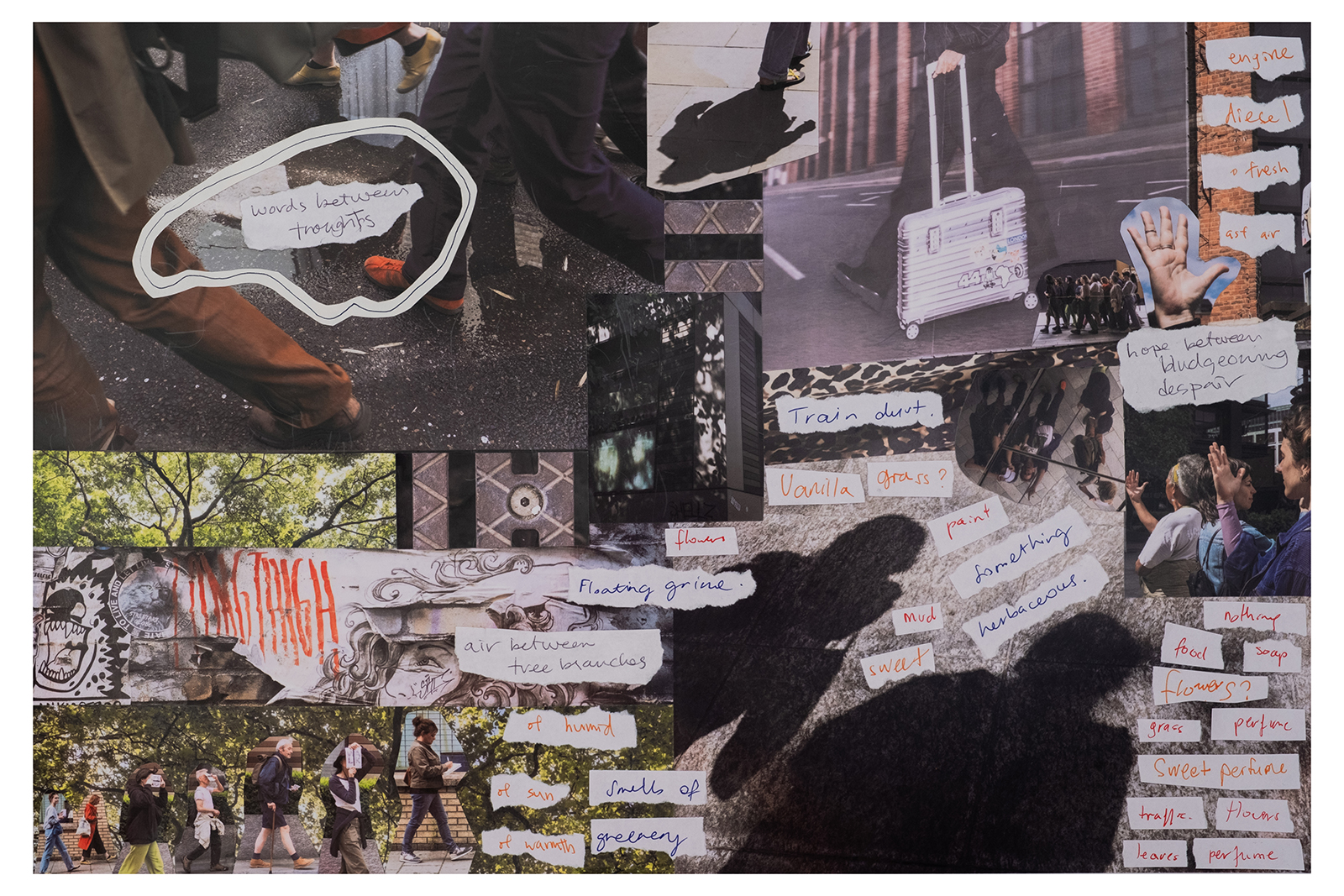

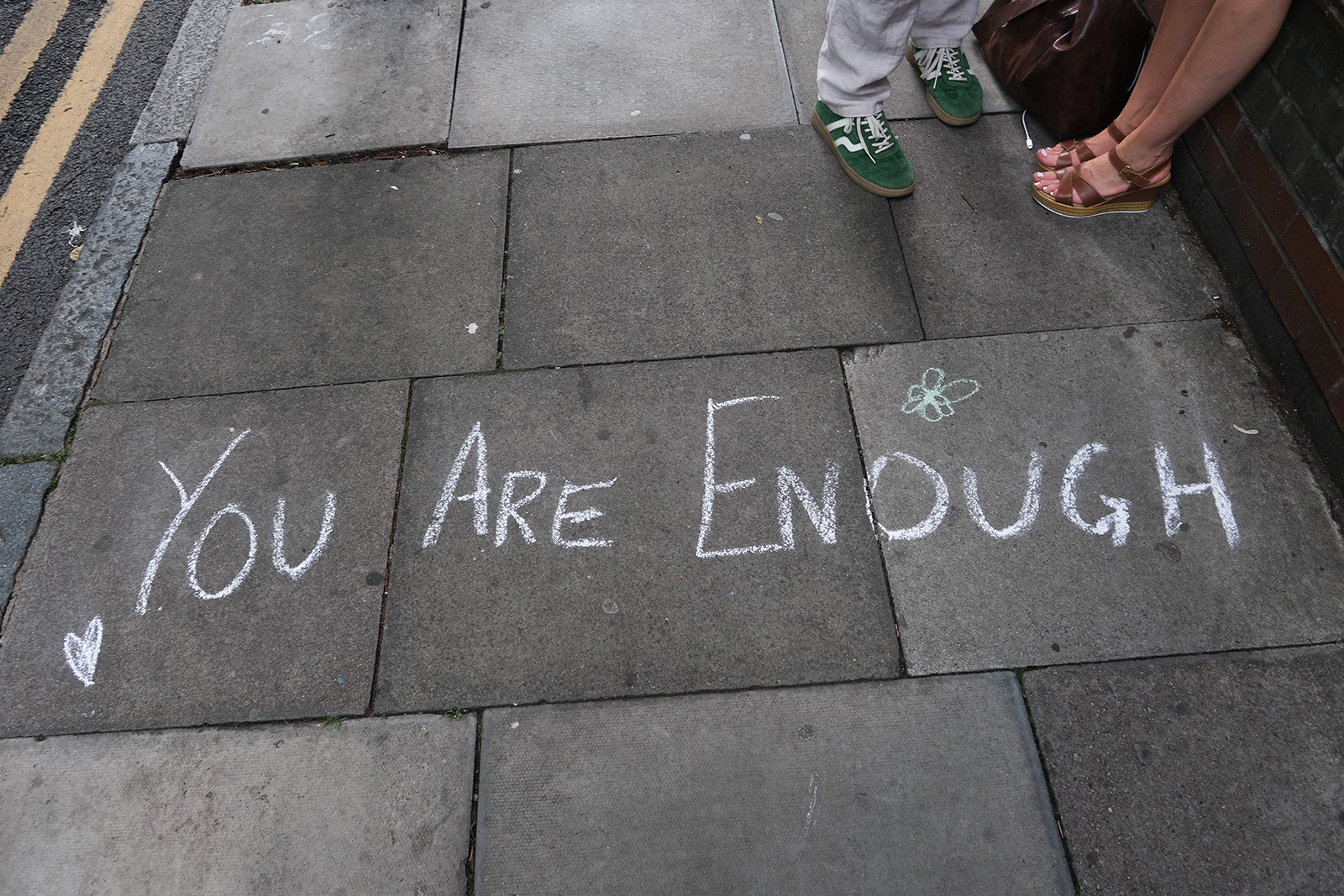

Now that I’m starting to have more resources, yes, some is going towards documentation but to be honest, I’m still very clear the experience will never be literally documented. What I’m more interested in is what I call traces. This fits well with walking practices. Sometimes I have different structures embedded within the walk that leave a trace. I work a lot with mapping. Or sometimes we’ll take one photo along the way and that’s a trace. For these BUILDHOLLYWOOD series of walks I’ve had an incredible resource and privilege, which I’ve not had before and it’s been amazing, so for each walk I invited a different friend, an artist who might not usually be thought of as having practice as documentators, but they are artists and friends whose work I really admire and feel connected to.

For each of them I gave a very open brief: to attend the walk, and either participate fully, or witness. It was up to them to come up with any sort of trace or response. And it’s been fantastic, really enriching because I’ve had responses ranging from poems to collages to audio files to Polaroid, photos, film and video. Also, I’ve learned when I have the money it’s good to commission a written response. So, it’s all about these different after tastes, ripples and traces rather than any conclusive documentary object.

At the final event we will have a map, consisting of all the maps that people have made at the start of each walk reflecting on how they got to The CarWash on that day and it’s amazing to see them all collaged together. And finally, because I’m always working with others, I’ve almost never made a walk where it’s just me walking, it’s always about inviting others and their responses become very much part of the work, respecting how they want to be represented (or not!) in the final documentation. Or how they can also withdraw at any point is all part of taking care of the work.