Where does your interest in bringing social awareness into your art practice come from?

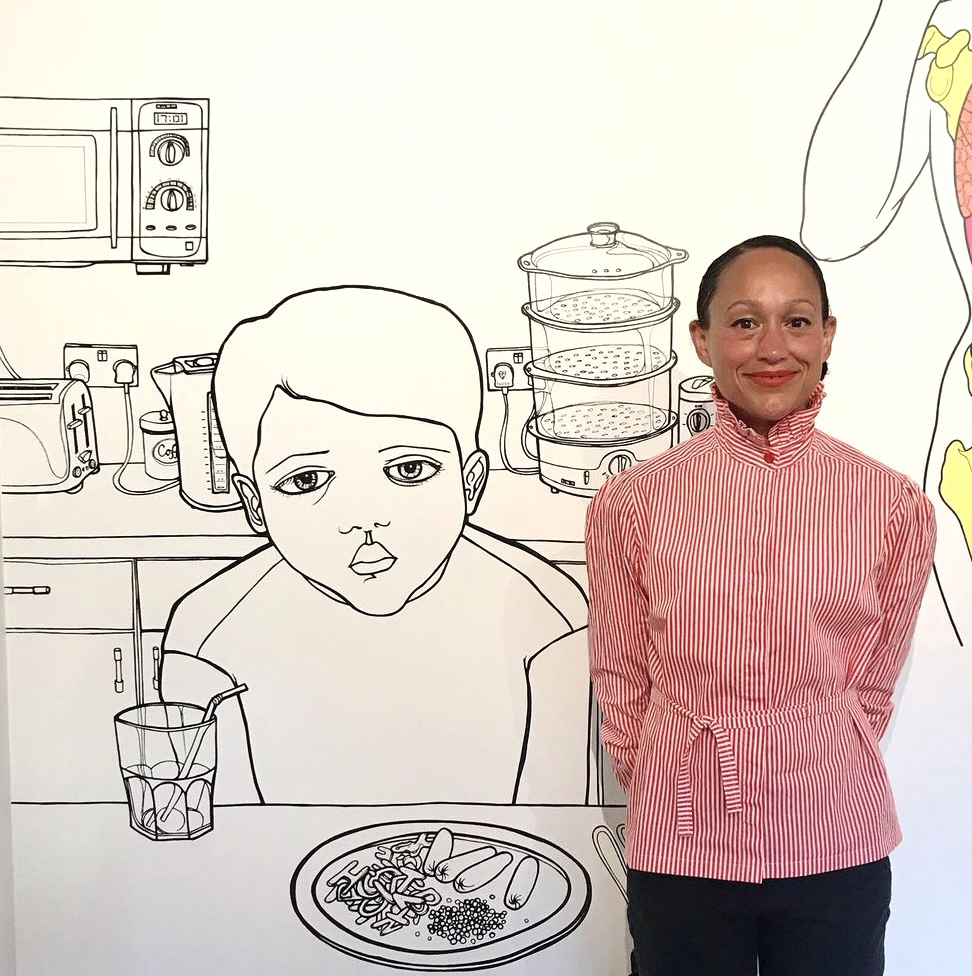

At school I spent a lot of time watching and observing people. My upbringing was quite particular: I have a black mum and a white dad so I was always aware of these different cultures and boxes that I never quite fitted, so again, I felt like a bit of an outsider. My parents got divorced when I was 7 and then we went from living in a house to living in a Bed and Breakfast to living in a council flat. There was a lot of fluctuation and I never quite settled (even though we were in the council flat for 10 years). I then went to sixth-form college in quite a wealthy part of north west London where I was introduced to people who had tennis courts and swimming pools in their back gardens. That was really eye opening, and another opportunity to observe different people and their interactions. One time, my friend came to knock for me on my council estate on her white pony called Sparkle! I wasn’t there, I was doing my Saturday job at the local supermarket!

That’s quite a colliding of worlds. Do you think it’s your awareness of these differences from such an early age that harnessed your desire to make art that engages with social issues?

That kind of jarring of different cultures and social strata had a strong impact. It felt like my middle-class friends had more freedom, or more options… they had access to things that I didn’t and yet being with people like that also gave me a passport into different communities and establishments that I wouldn’t have had access to on my own.

That interest in freedon – especially the sense of freedom that the context of a city offers is a really important to you. Can you tell us more about that?

I have an interest in our streets, in how we use our streets, and who they’re for. One of the jobs I do alongside making art is working for a small organisation called Solve the School Run which is about trying to reduce car use and school-run traffic. I spend a lot of time thinking about this, taking photos of streets, meeting with councillors etc and thinking about how we can make our streets safe and accessible for everyone.

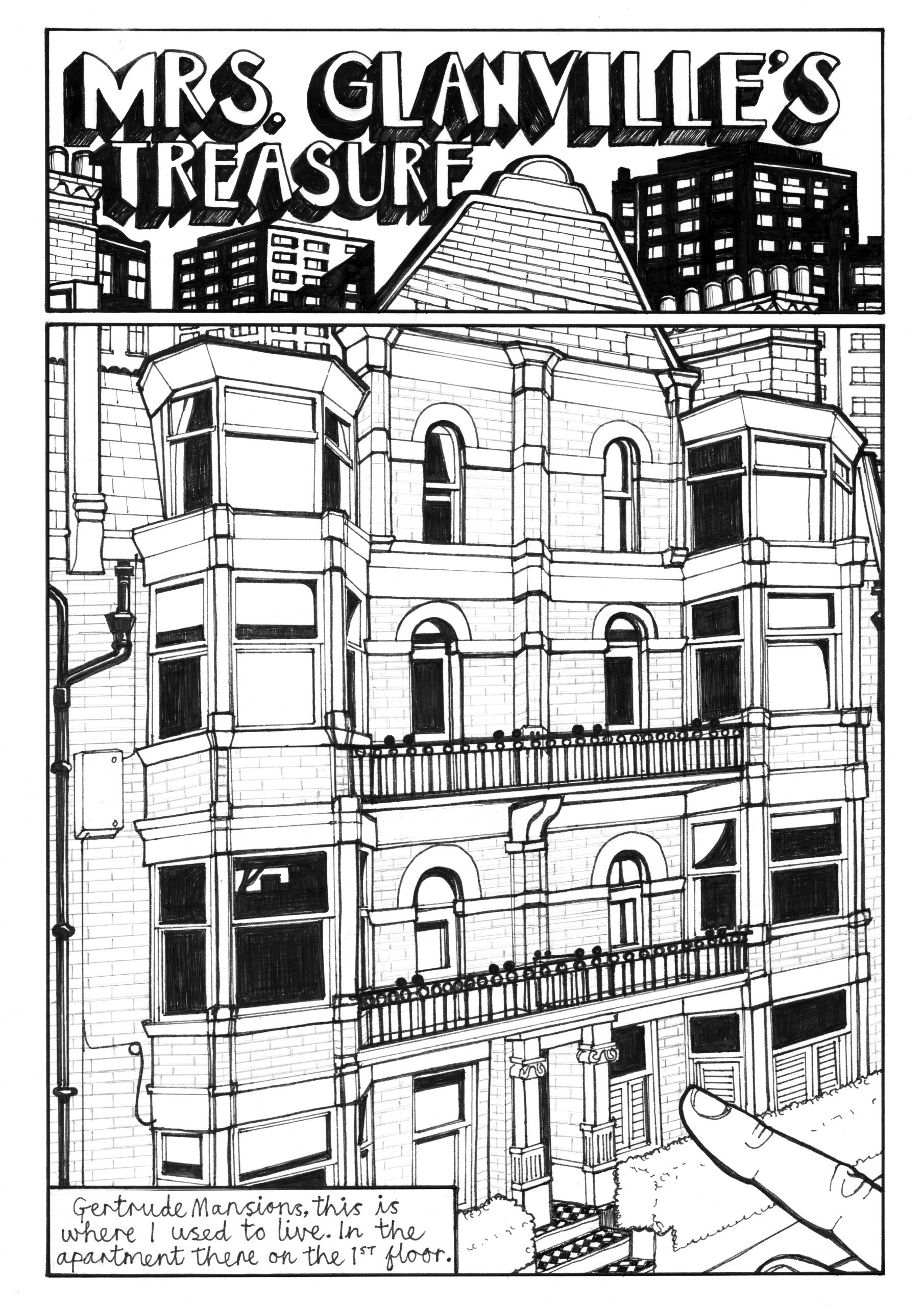

Hence your work ‘Where’s my Supertram?’ which appears on the route of Bristol’s old tram route.

The main generator for the trams in the city was bombed in 1941 marking the end of trams in Bristol. After that, buses and private cars became the main forms of transport. Now, given the interest in reducing pollution and the cost of car ownership, trams feel like a great option again. Discussion about bringing in a tram system in Bristol has been rumbling on for years but for various reasons these kinds of big infrastructure projects get shelved by local councils.

Before we had this conversation you sent me an image of Old Market from 1908 picturing the old tram which is really evocative.

Yes, the road is busy with people, there are no road markings, and hardly any vehicles visible or street furniture. Now our streets are so full of traffic but also signs and street furniture like bollards and things that tell us how we can and can’t move around the city.