At the show we talked a bit about the term “troubling canons” in art, that a healthy canon of feminist art history, say, isn’t to do with fixing – defining, including or excluding entities once and for all – but should be about building bodies of knowledge that grow, evolve and are constantly tested through time. Do you see part of your role in curating as addressing, perhaps subverting existing art history?

Well, not so much with this show but I do try and work with artists who have, shall we say a less conventional background to their thinking and practice. Maybe they haven’t come through a standard college or university route to arrive at what they do. I would say that the shows I curate tend not to play by the rules. Conventional art history is important to know but maybe so you can speak against it, to challenge tired but still prevailing points of view.

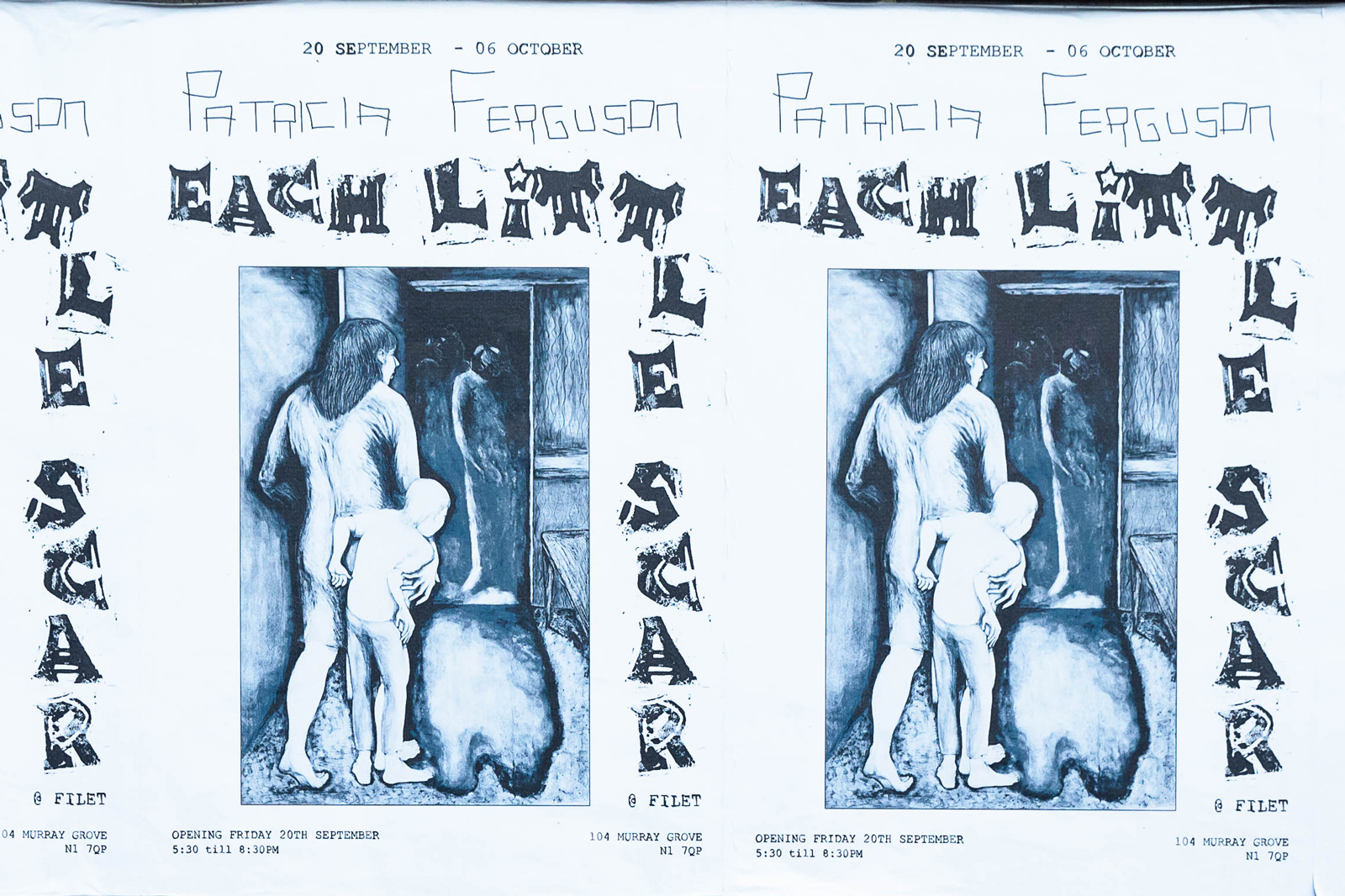

Researching for the public program of artists’ events that runs parallel with Each Little Scar show I made a number of visits to Ireland, north and south, to seek out what you might call more political artists, or rather individuals and collectives whose work is rooted in real life concerns. Who demonstrate social convictions in their art practice. Political with a small ‘p’. Not people seeking to promote one party line over another but artists who are questioning structures.

For example, two artists in the public program, Emma Campbell and Clodagh Lavelle belong to the Array Collective. Array is a group of multi-disciplinary Belfast based artists and activists who create collaborative actions – protests, rallies, workshops, exhibitions and events – in response to pressing socio-political issues including abortion, mental health, racism, homophobia… In short, they’ll hitch their anger, their concerns, to the many and varied disenfranchised groups and work with them to promote awareness and change, to challenge the ambivalence shown by those in power to people who are vulnerable.

For Each Little Scar’s public program, I wanted to show, and work with artists from the broad cross section of people who make up Irish society. Aideen Barry is a visual artist working across disciplines and subjects including domestic labour, classism, environmental changes and more through film, performance, sculpture, text and experimental lens-based media. Alice Rekab takes her own mixed-race Irish-Sierra Leonean identity as a starting point to explore the idea of the body, the family and the nation as reflections of one another. Born and bred in Dublin her work offers a unique perspective on what it means to be Irish today. I think it’s important work, to use the public program as a way to identify and break, or at least interrupt, isolated experiences of oppression. To promote more understanding, inclusion, to offer help and hope. I think Trisha would’ve done that herself if she were still here.