Whilst conflicts and crises differ from case to case, what are the pillars of War Child that stays the same no matter what the circumstances?

War Child’s belief is that no child should be affected by war ever. The mission is to reach children quickly when a conflict breaks out and stay long after the cameras have gone to help them recover for a safer, brighter future. One of the pillars of the work is protection, which is about creating safe spaces and helping children who have been separated from their families. And that work is carried out with lots of other agencies who do amazing work in areas that they specialise in, like shelter, food, and water.

The second pillar is education. We try to get children back into education as quickly as we can, which could be anything from setting up informal learning centres to training teachers.

And the third pillar is what we call psycho-social support. Basic psychological first-aid and mental health support. I think that’s often where War Child makes the biggest impact and specialises in the most. Because the sooner you can reach a child who has experienced the brutality and horrors of war, the sooner they can process that trauma, the less long-term impact on their livelihood and their ability to claim their childhood back, is improved exponentially.

We also have a pillar of livelihood as well, which could be anything like business training or giving micro-loans to help the local economy recover.

Considering the long-term impacts of war, how important is that factor of longevity in War Child’s work?

The longevity is absolutely vital. Ever since War Child was started by David Wilson and Bill Leeson in 1993 after visiting Bonsia during the Yugoslavian war, there has been an emphasis on understanding the impacts of trauma. One analogy I always use to describe the stages of work is that you can give a child a bed, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that they will be able to sleep at night.

And every place affected by conflict is different. For example, in the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of Congo, a large proportion of our work is concerned with helping children affected by armed groups – child soldiers. This could involve identifying them, getting them out of militias, helping them deal with trauma experienced, and also getting them back into their communities because once they have been taken or volunteered themselves, they can face a lot of stigma.

Whereas in Yemen, a lot of War Child’s work is cash grants. It’s a country where a vast majority is at risk of severe malnutrition. We want to be working in education and psychosocial support there – and we are to an extent – but the most acute lead is survival. So, it’s simply about granting money for families to spend. There’s often a bit of stigma attached to this too – “you’re sending cash, you don’t know where it goes” – but that cash goes into the local ecosystem and dignifies people to buy what they want. Sometimes it’s no good sending people 5 litres of oil or 2kg of rice when they’ve got a teenage daughter who desperately needs some tampons. It empowers them to make their own decisions and the money goes back into the local community. So, our work is very nuanced and long-term.

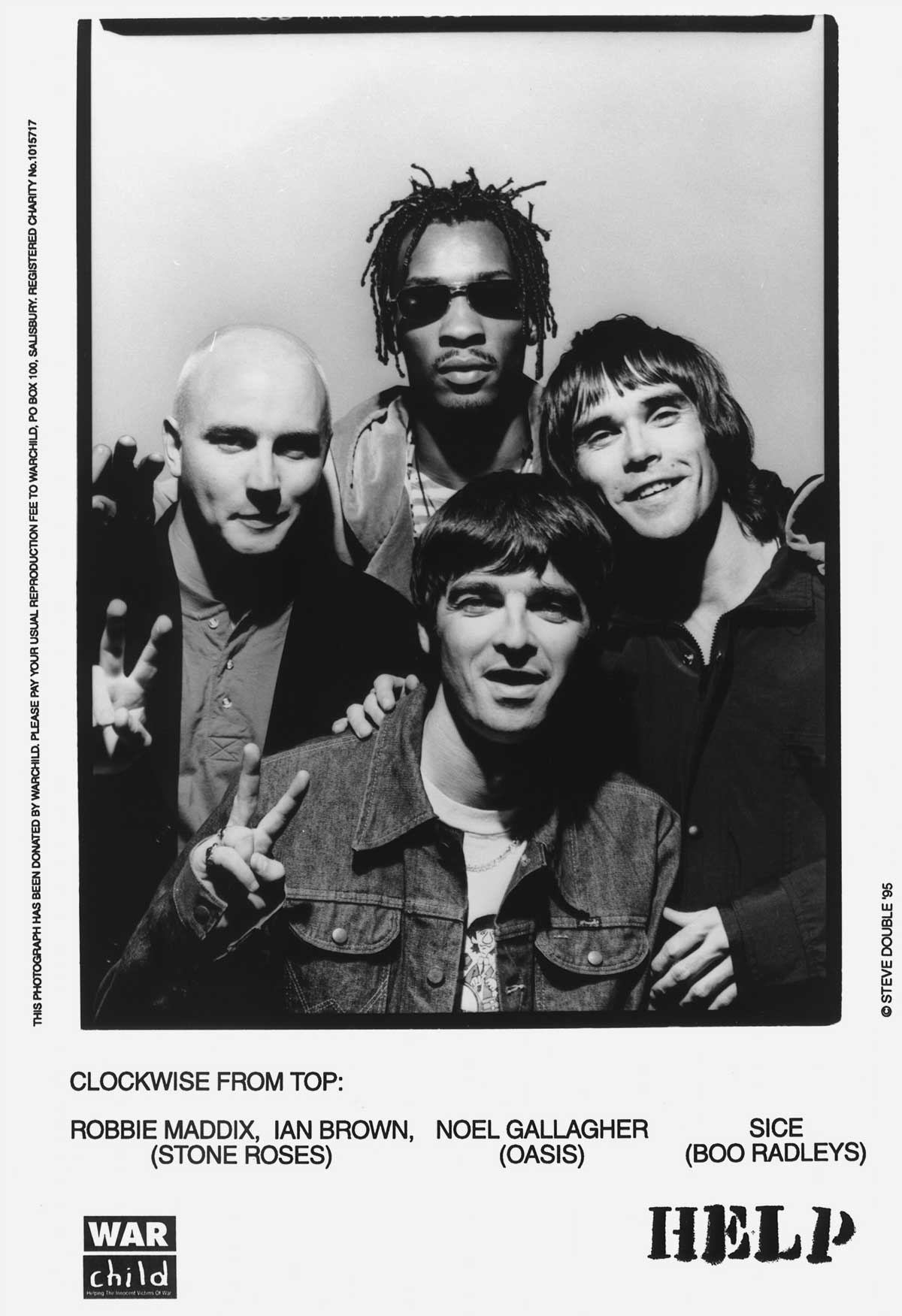

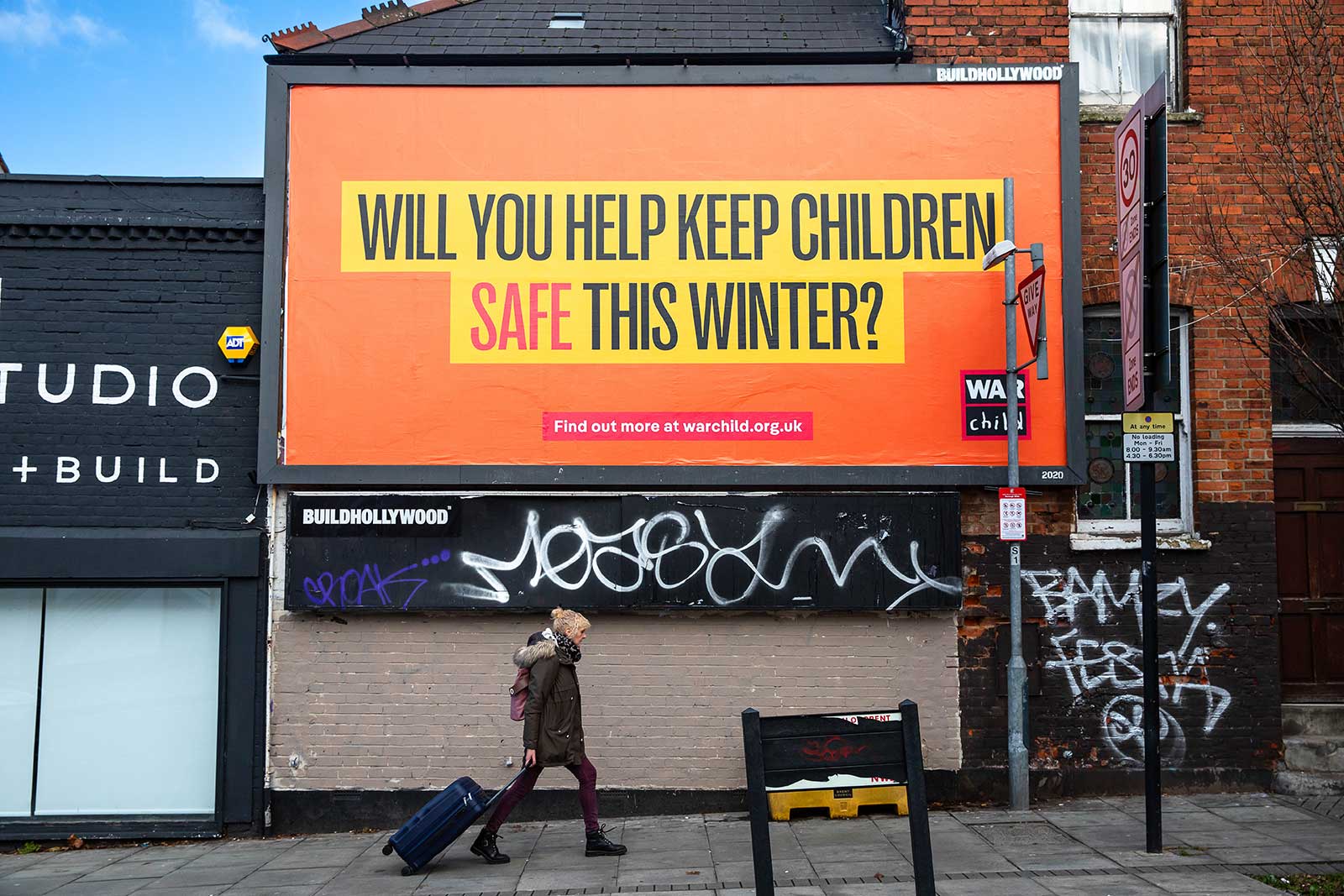

Help poster (1995)

Help poster (1995)

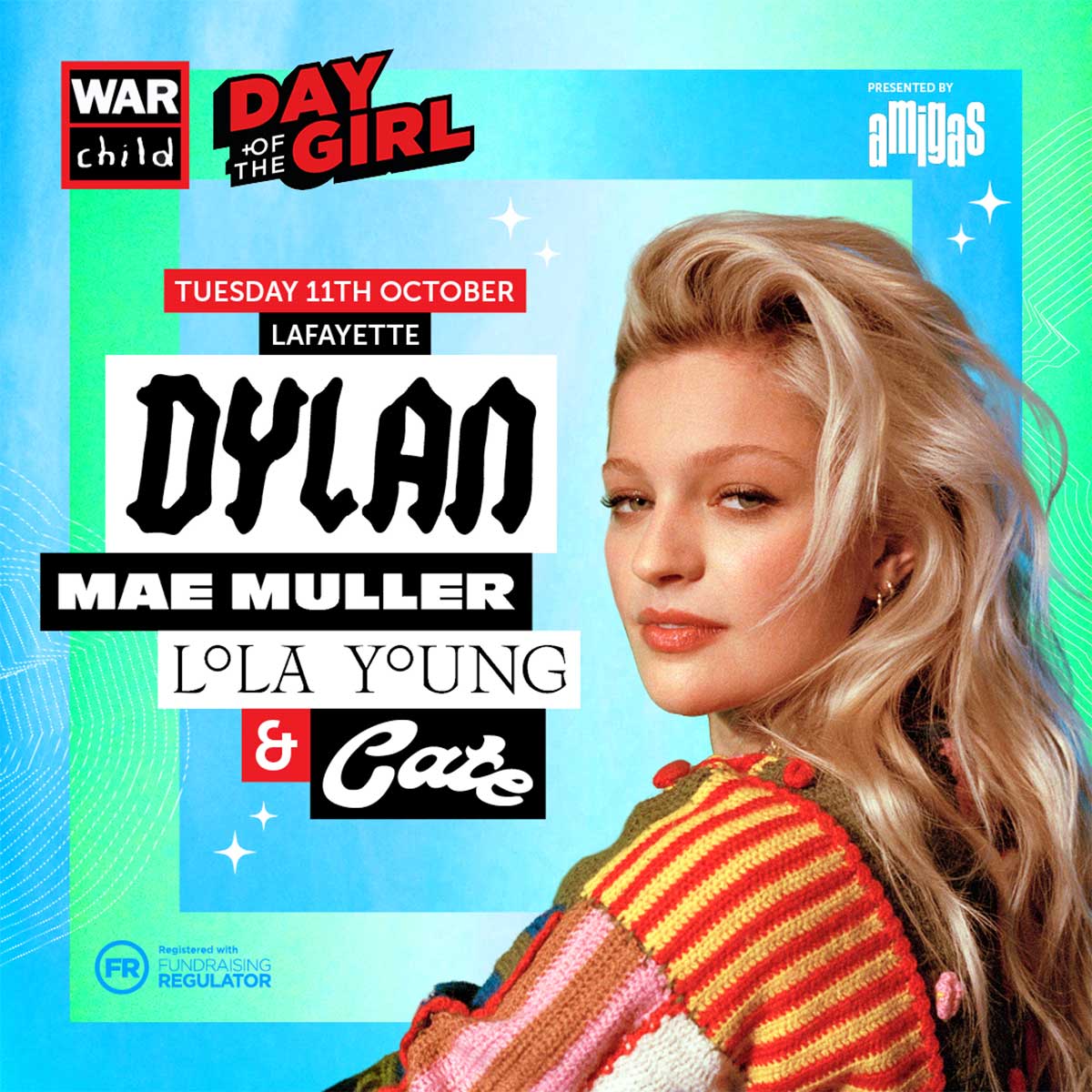

Day of the Girl, celebrating remarkable girls and women around the world

Day of the Girl, celebrating remarkable girls and women around the world

Day of the Girl, celebrating remarkable girls and women around the world

Day of the Girl, celebrating remarkable girls and women around the world

Democratic Republic of Congo

Democratic Republic of Congo

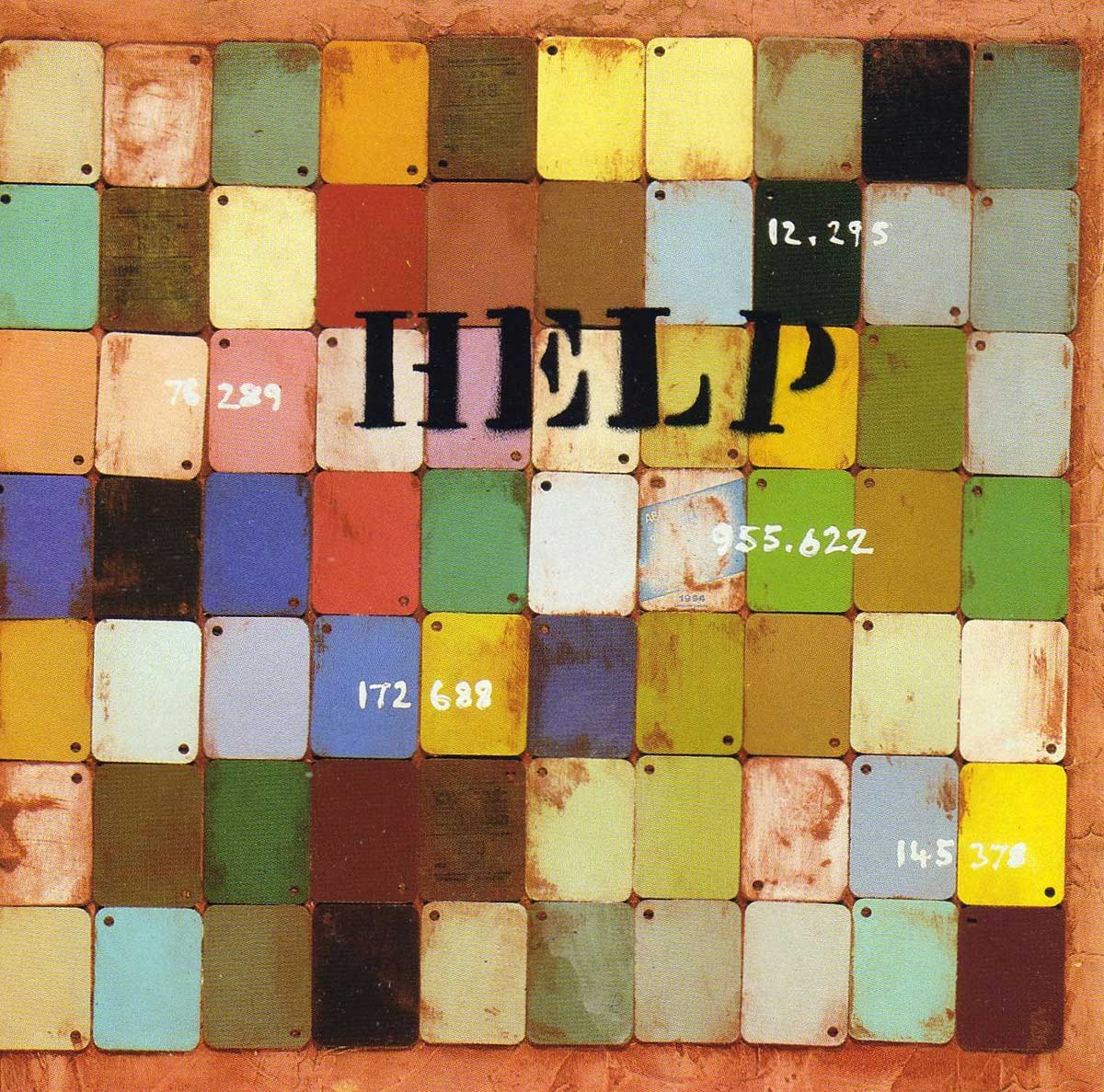

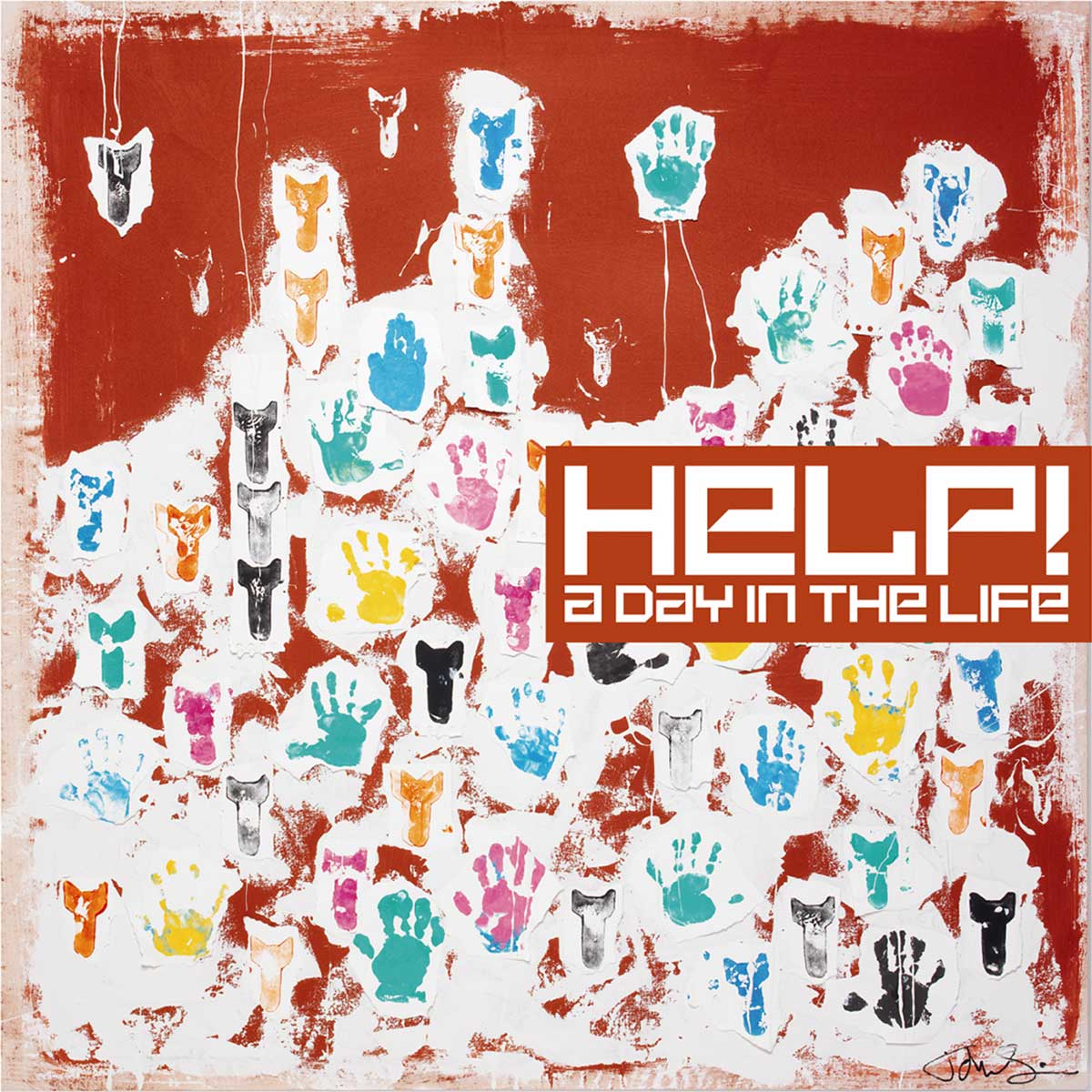

Paul McCartney, Oasis and Paul Weller come together for the album Help (1995)

Paul McCartney, Oasis and Paul Weller come together for the album Help (1995)

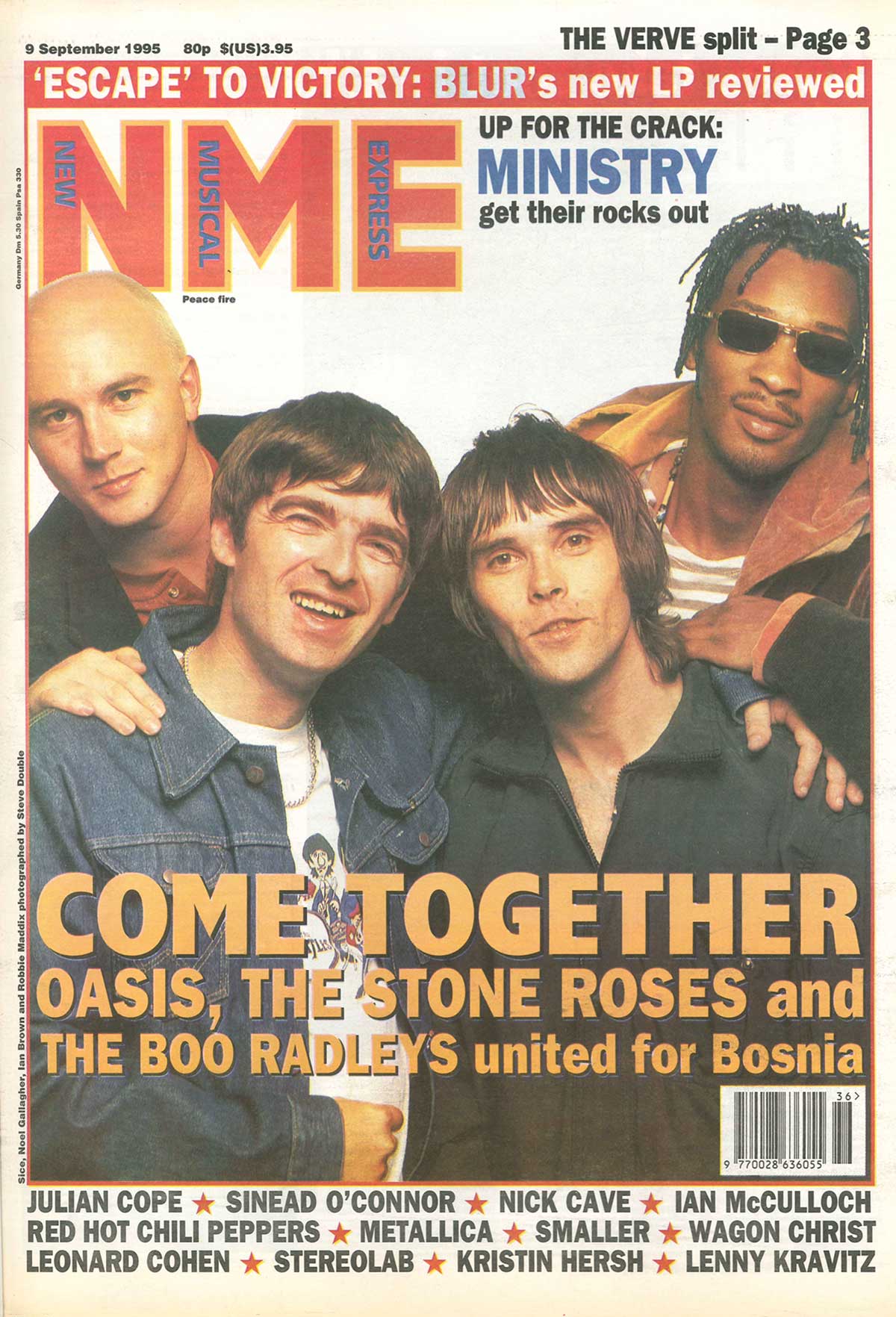

NME, Help (1995)

NME, Help (1995)

Arctic Monkeys live at the Royal Albert Hall

Arctic Monkeys live at the Royal Albert Hall

Brits (2009), Coldplay, Killers and Bono

Brits (2009), Coldplay, Killers and Bono