Partnerships

The curators of London Short Film Festival talk us through its 21st year

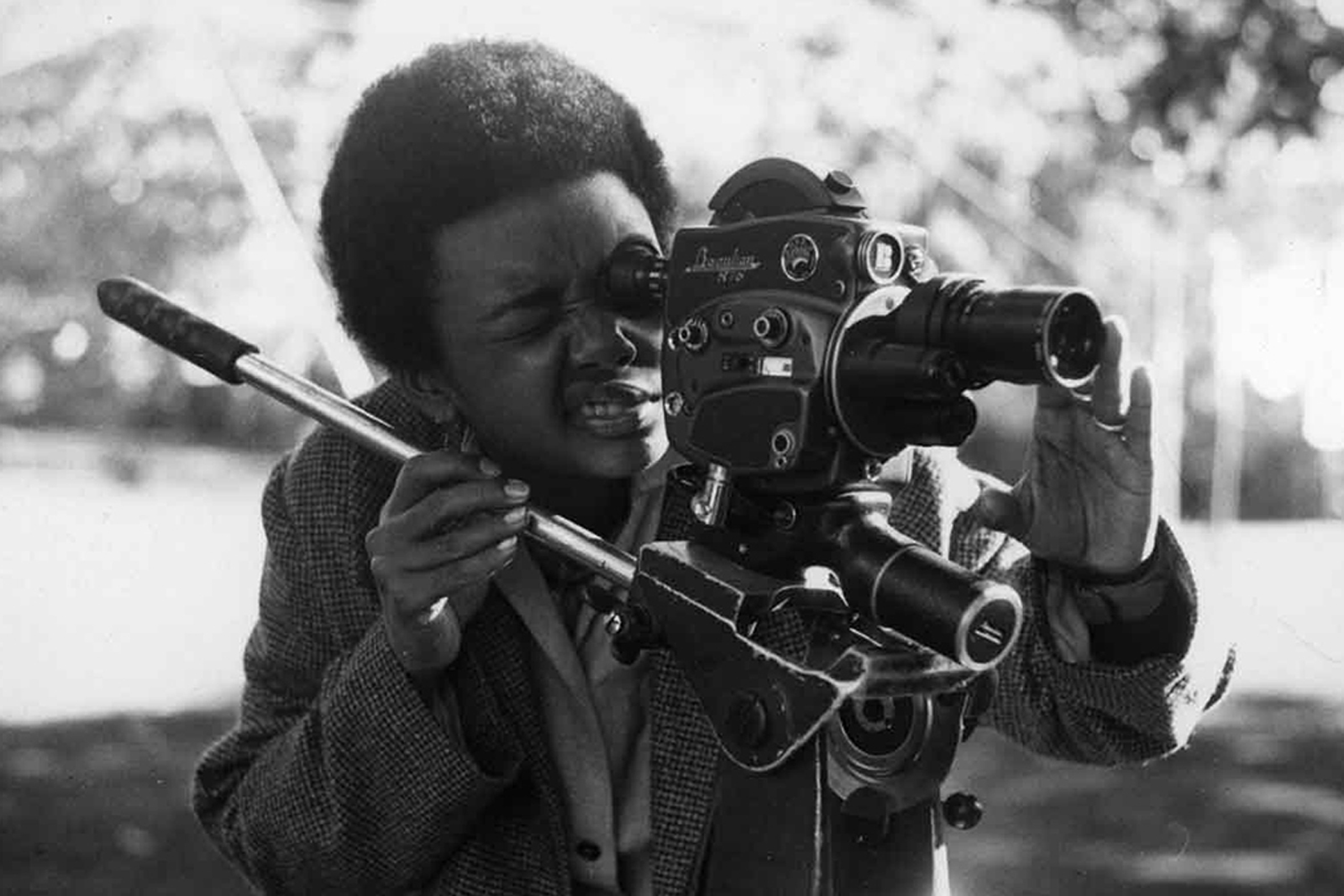

Philip Ilson, the co-founder of London Short Film Festival, wasn’t expecting the festival to have such a long life. He launched it with Kate Taylor, who is now with the BFI and the Edinburgh International Film Festival, off the back of a film club he was running in London. “The club, which we called the Halloween Society, was started in the late 90s as an underground alternative film space. A friend and I had been making short films together, and the club was part of a burgeoning explosion of the slightly left field alternative underground,” he tells us now. The club took off, and Philip was approached by the Institute of Contemporary Arts about putting on a short film festival.

Philip had been working with Kate Taylor on a temp job with the British Council, so they decided to start the festival together. They put on a four day festival, utilising his burgeoning connections with filmmakers and accepting submissions via VHS. They put on bands and other events alongside the screenings, and after a few years, it was enough of a success to change their name to London Film Festival and expand to venues like the Soho Curzon cinema. Now in its 21st year, the festival is Philip’s full-time job.

23.01.24

Words by