Your Space Or Mine

New Year, new poster collaboration with artist Mark Titchner: IT’S THE HOPE THAT KEEPS US HERE

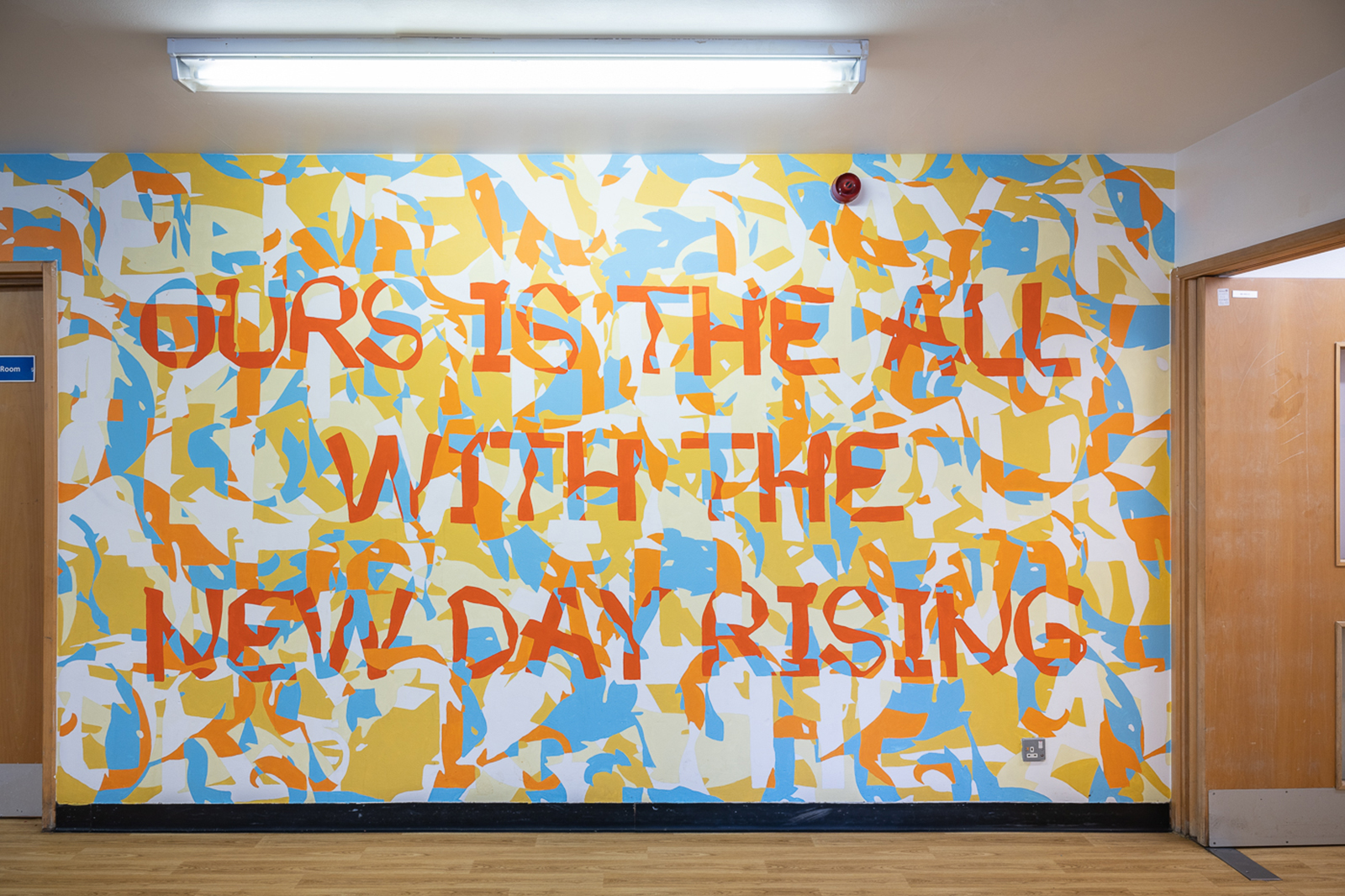

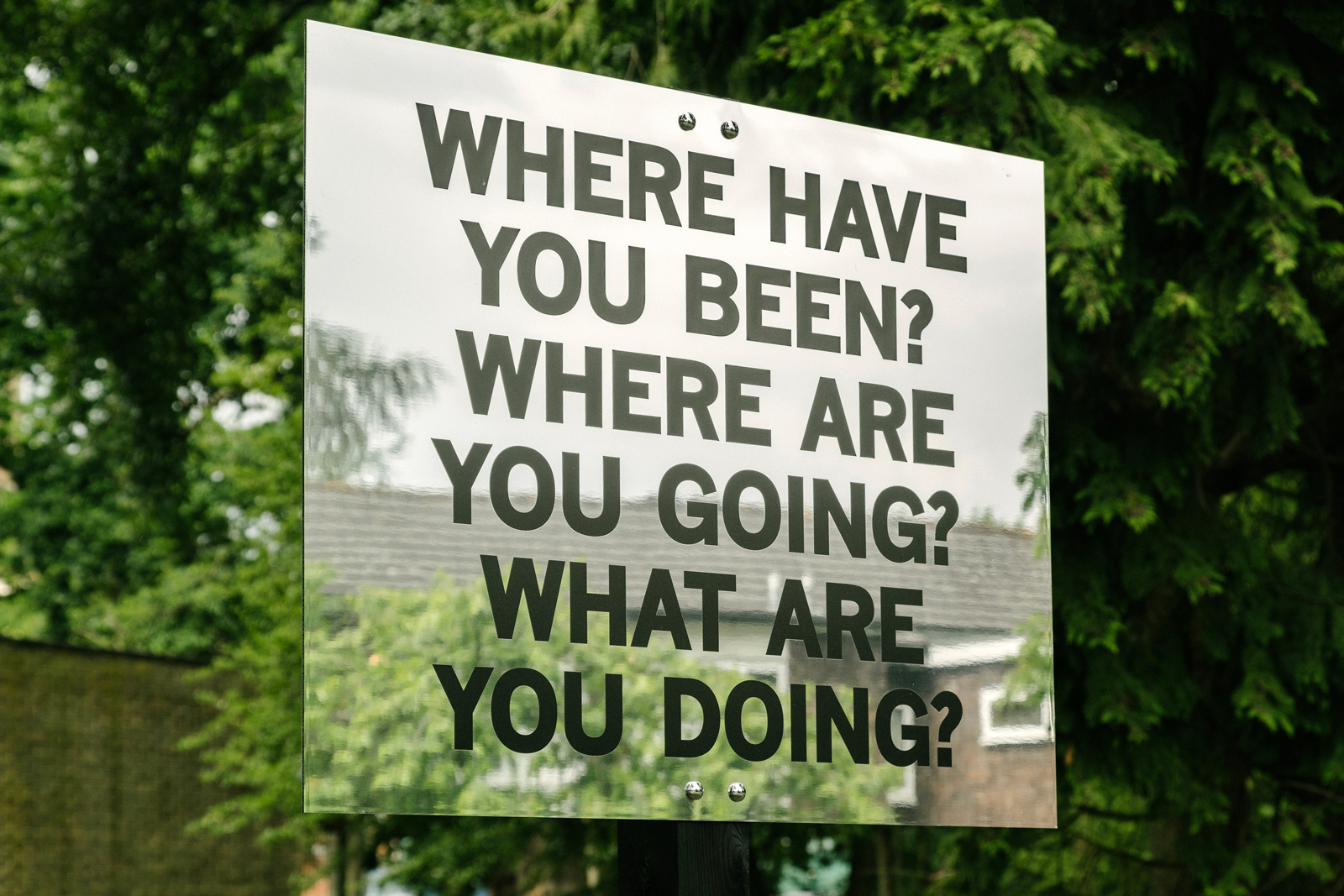

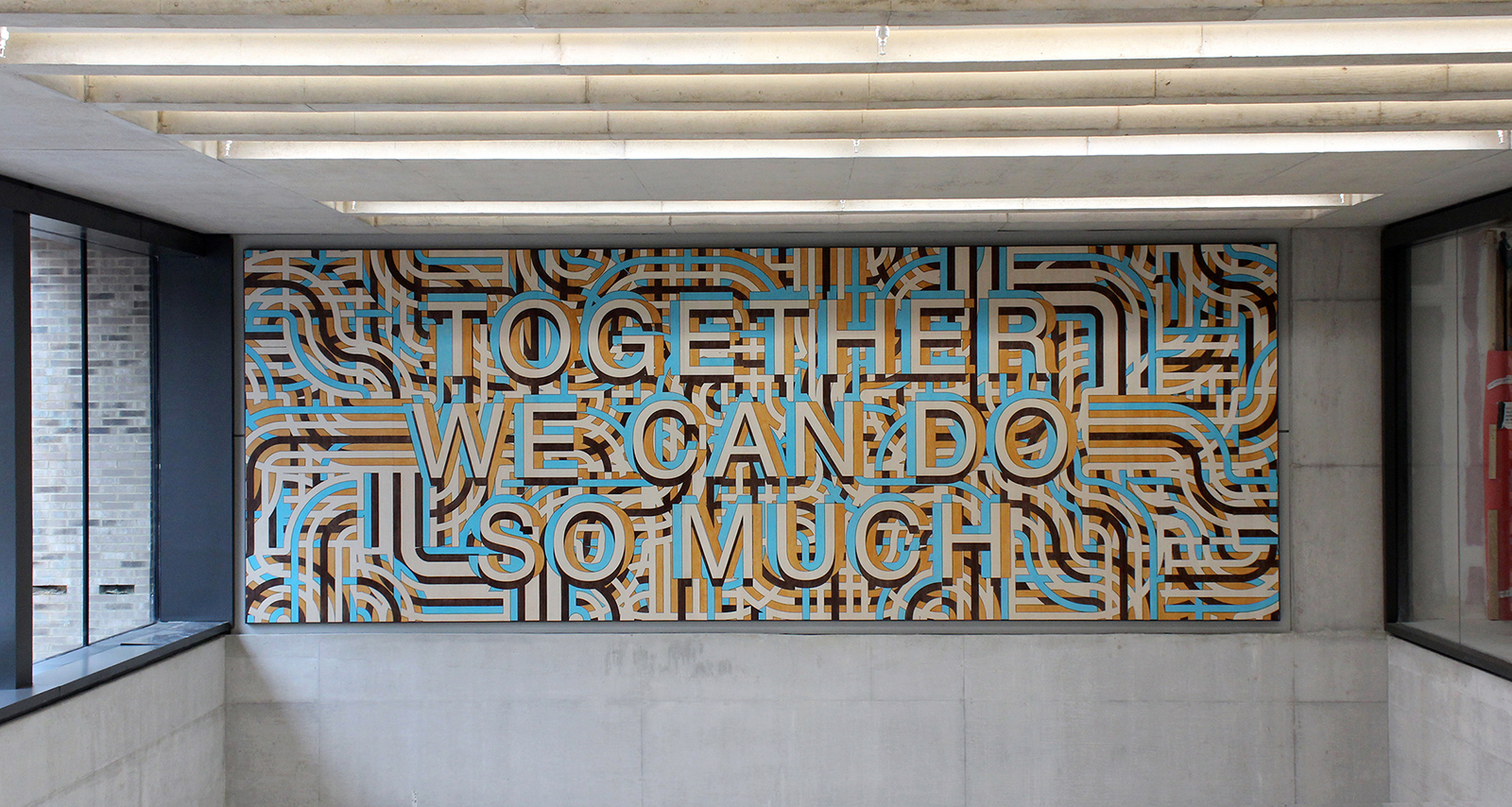

Mark Titchner’s art practice takes many and varied forms. He works across a range of mediums: digital print, video (often accompanied by hypnotic, sometimes ear-shocking soundtracks), installation, site specific painting and 3D objects. Much of the artist’s output is situated in the public realm: libraries, hospitals, stations, in the street, even football stadia. In very broad terms an aesthetic thread that continues through the work is the use of enigmatic text combined with arresting pattern.

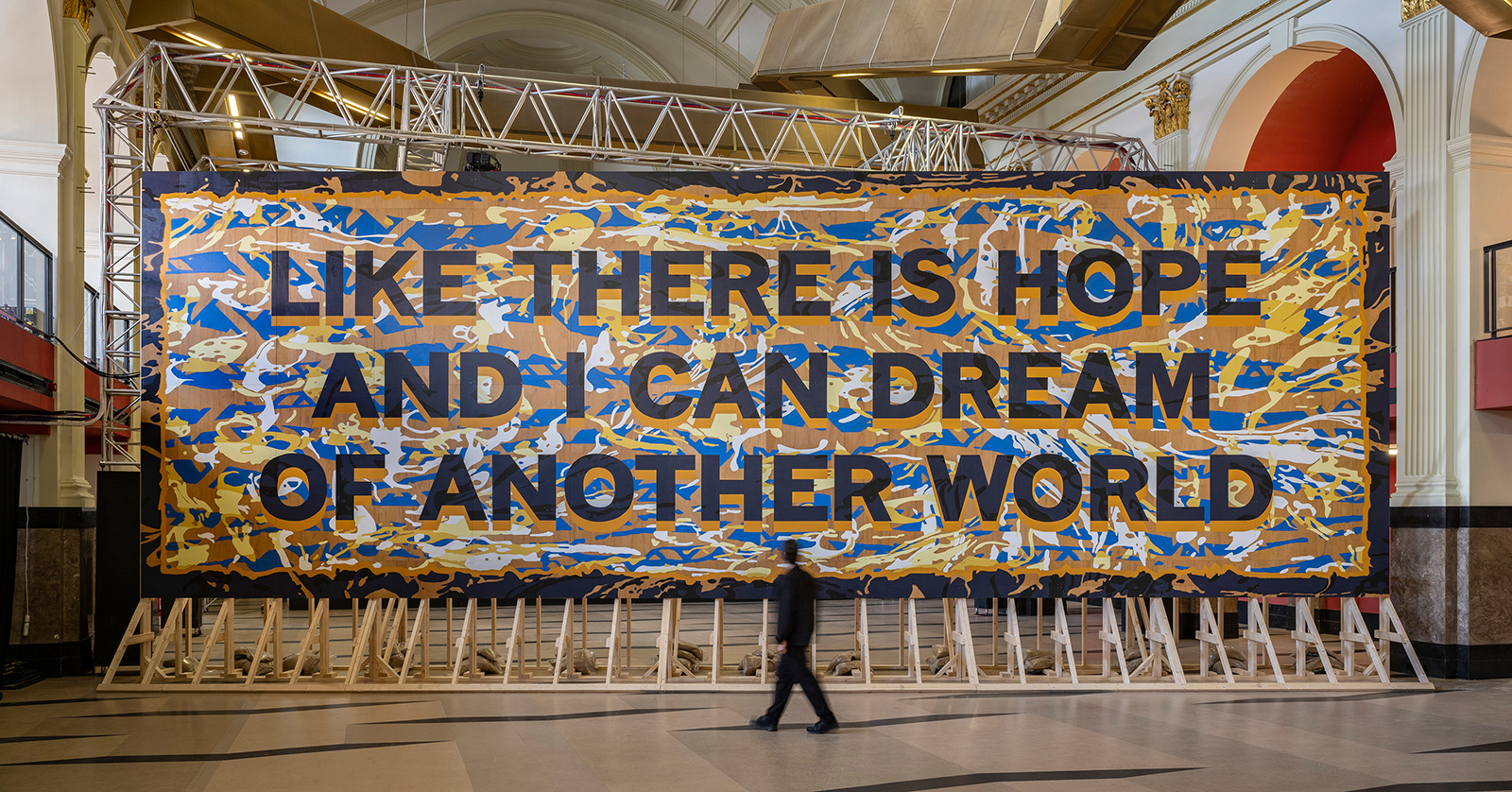

The last time we crossed paths IRL was at the social enterprise and charity – now sadly closed – House of Saint Barnabas in Soho. Titchner’s show there – titled PAINTINGS WITH WORDS AND PAINTINGS WITH WORDS AND NUMBERS – was an exhibition of exquisite economy. At another extreme, and just to begin to demonstrate the breadth of the artist’s production, Titchner was invited to make work for an ambitious and conscience raising partnership between Hauser & Wirth and mental health changemaking charity Hospital Rooms. LIKE THERE IS HOPE AND I CAN DREAM OF ANOTHER WORLD is a 15m long, almost 6m high mural hand painted on fifty-one plywood panels that has been shown in different venues but is destined to be permanently installed at The River Centre, a new NHS mental health hospital in Norwich. This is an artist whose creative output continually surprises, challenges and with this latest poster work conceivably nurtures passersby. Having collaborated with Mark back in 2020 to display PLEASE BELIEVE THESES DAYS WILL PASS during the pandemic, it’s a pleasure and privilege for BUILDHOLLYWOOD to share Titchner’s work once again, featuring IT’S THE HOPE THAT KEEPS US HERE throughout the UK.

An overarching subject would seem to be addressing and reflecting on the human condition. The range and depth of his work seems to offer up a kind of test laboratory, both proposing and wondering how we communicate, receive and deal with different facets of life’s complexity. In short, it’s a mission to investigate how we think, feel, behave and care for one another. The artist kindly agreed to answer a few questions to explore his creative process in a bit more depth.

15.01.25

Words by