Partnerships

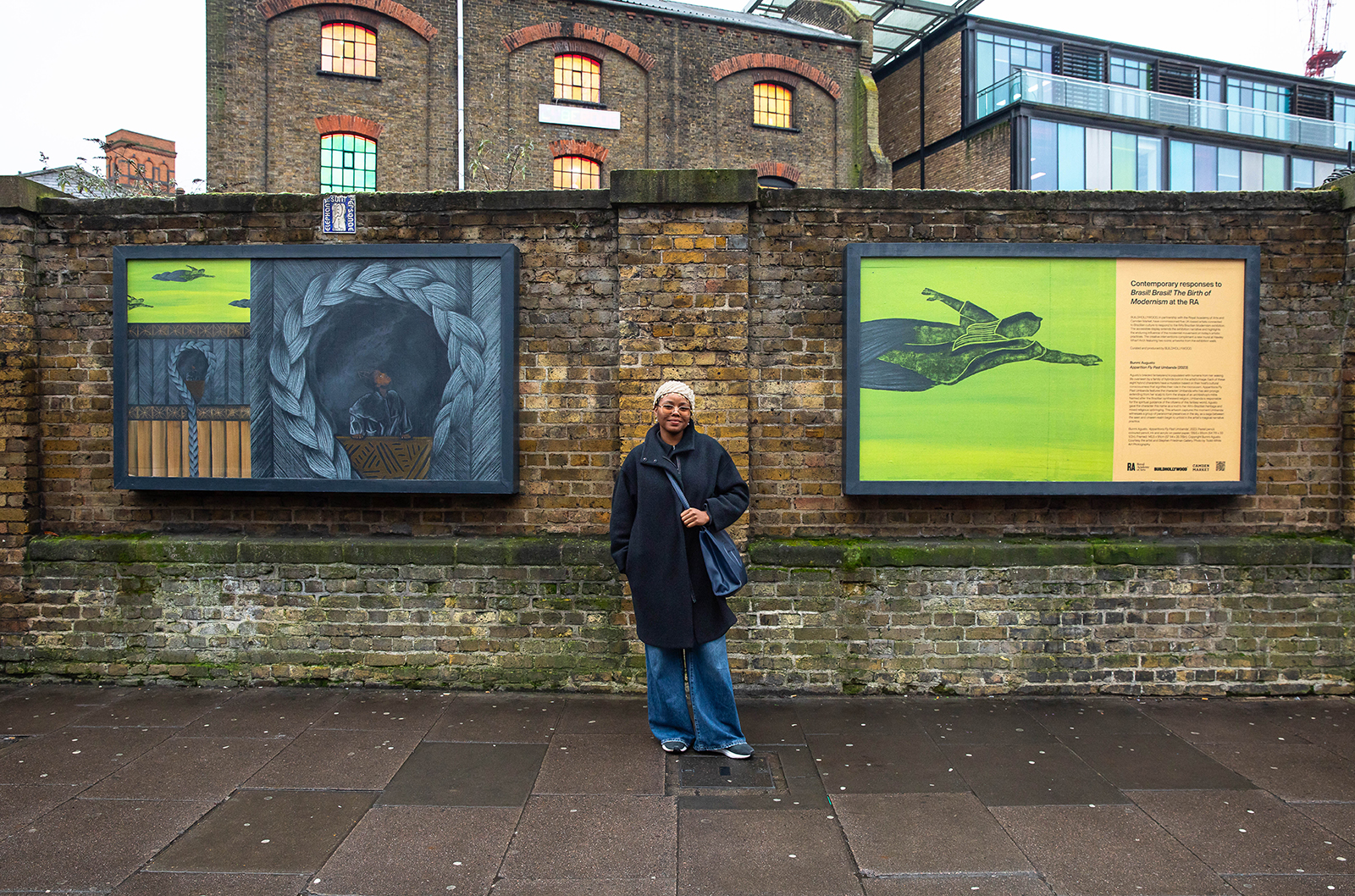

Brasil! Brasil! A street-side ode to Brazilian modernism and migration

In collaboration with the Royal Academy of Arts and Camden Market, BUILDHOLLYWOOD presents a street-side celebration of Brazilian modernism in the heart of Camden Town. The five selected artists turn their hand to reimagine the seminal Brazilian work featured in the Royal Academy of Arts, all in their own ways returning to the legacy of Brazil’s diasporic cultural identity. In its artistic candour and creative consideration, the responses to the RA exhibition Brasil! Brasil! are a stark reminder of the way our society depends on the legacy of migration, without which our British isle would be far poorer, in economy, community, and artistic integrity.

“Brazil is home to the largest Japanese population outside of Japan”, shares Fernanda Liberti, one of the artists featured in the BUILDHOLLYWOOD collaboration, “ it has the biggest African population outside of Africa, with more Lebanese people living in Brazil than there are Lebanese people in Lebanon”. Her own Syrian and Brazilian heritage speaks to the rich cultural complexity of Brazilian migration, with artist Gustavo sharing his own anthropological understanding of the very human history of migration. “Nations are built because of people that come and go”, he says, with his project in collaboration with artist JC Candanedo exploring the diasporic identity found in the Brazilian delivery driver population in the UK. “We can’t live without these people”, JC shares, “they have completely changed the way we live”.

12.02.25

Words by