Partnerships

Art meets action: Kaye Dunnings on curating United Notions for Massive Attack’s climate rallying cry

In the shadow of On the open plains of Clifton Downs, where Bristol’s own Massive Attack made their grand return to UK soil after five years, and art, activism, and sustainability collided in one of the most ambitious live events of the year.

On August 25th, the legendary band transformed their hometown into a large-scale canvas for climate action with Act 1.5—a pioneering, low-carbon event that aimed to set a new standard for how festivals and gigs could operate in a world facing ecological collapse. Like anything capable of creating worthwhile change, the festival—and its art installations—did not come without challenges, be they financial or logistical.

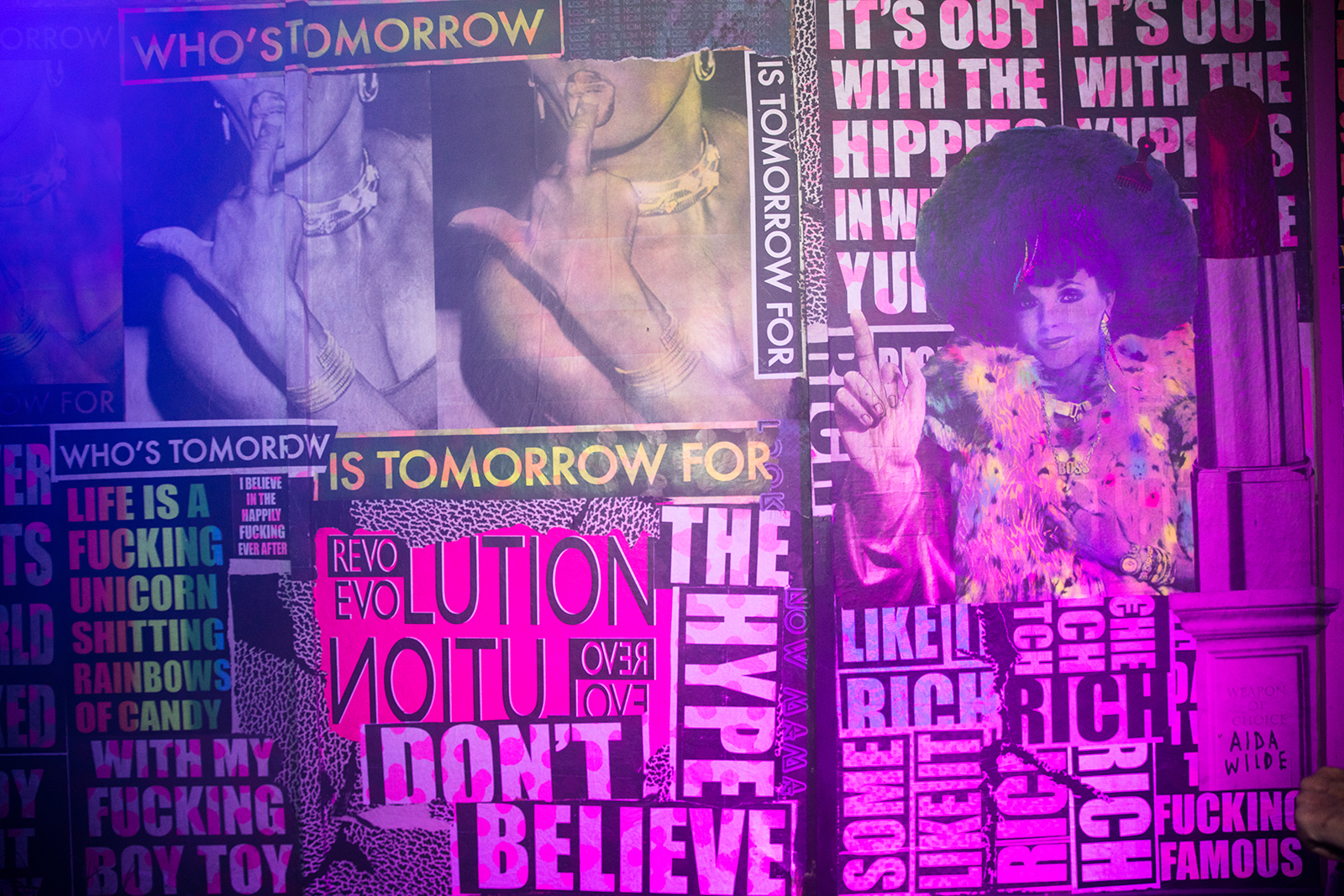

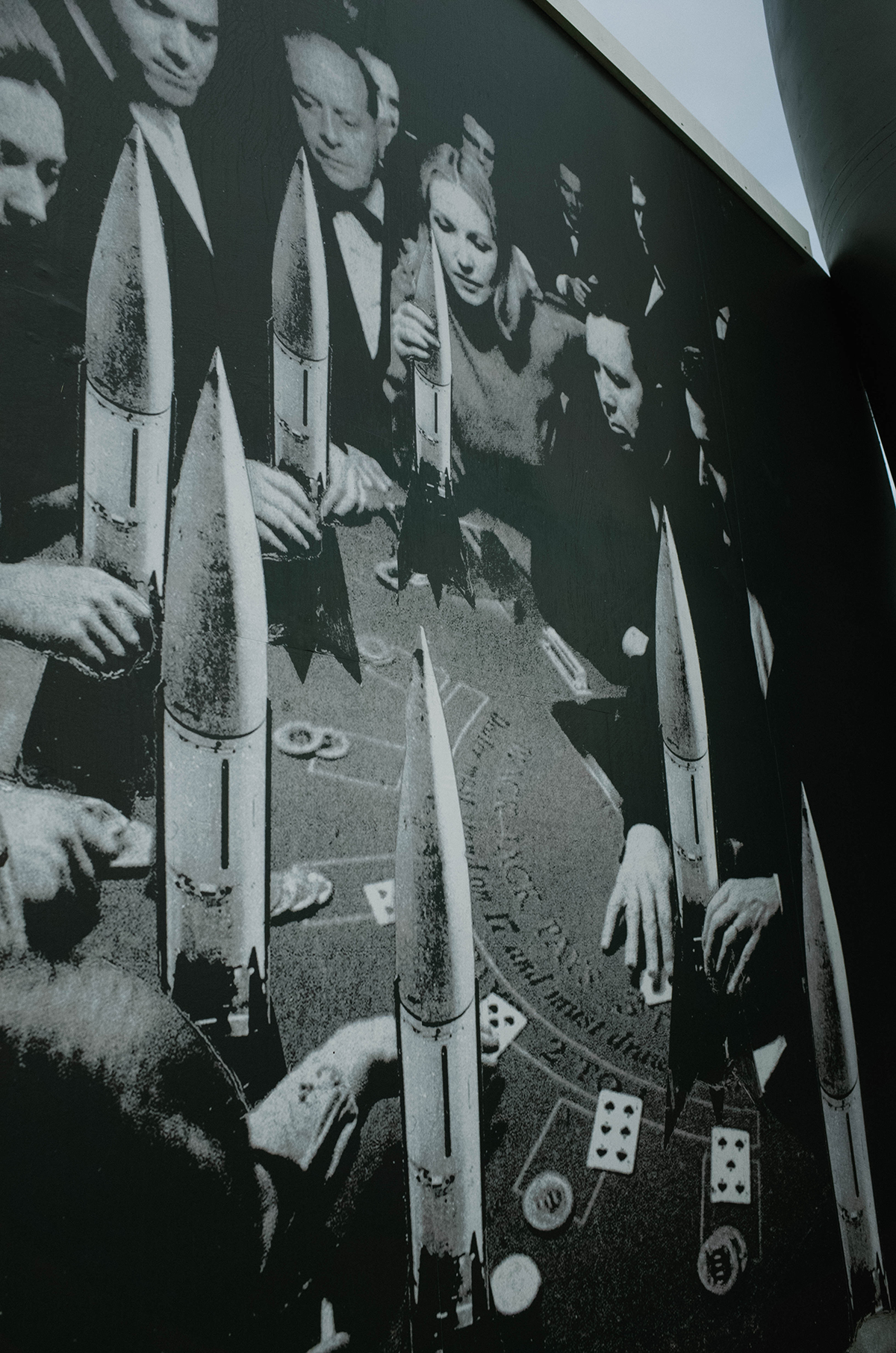

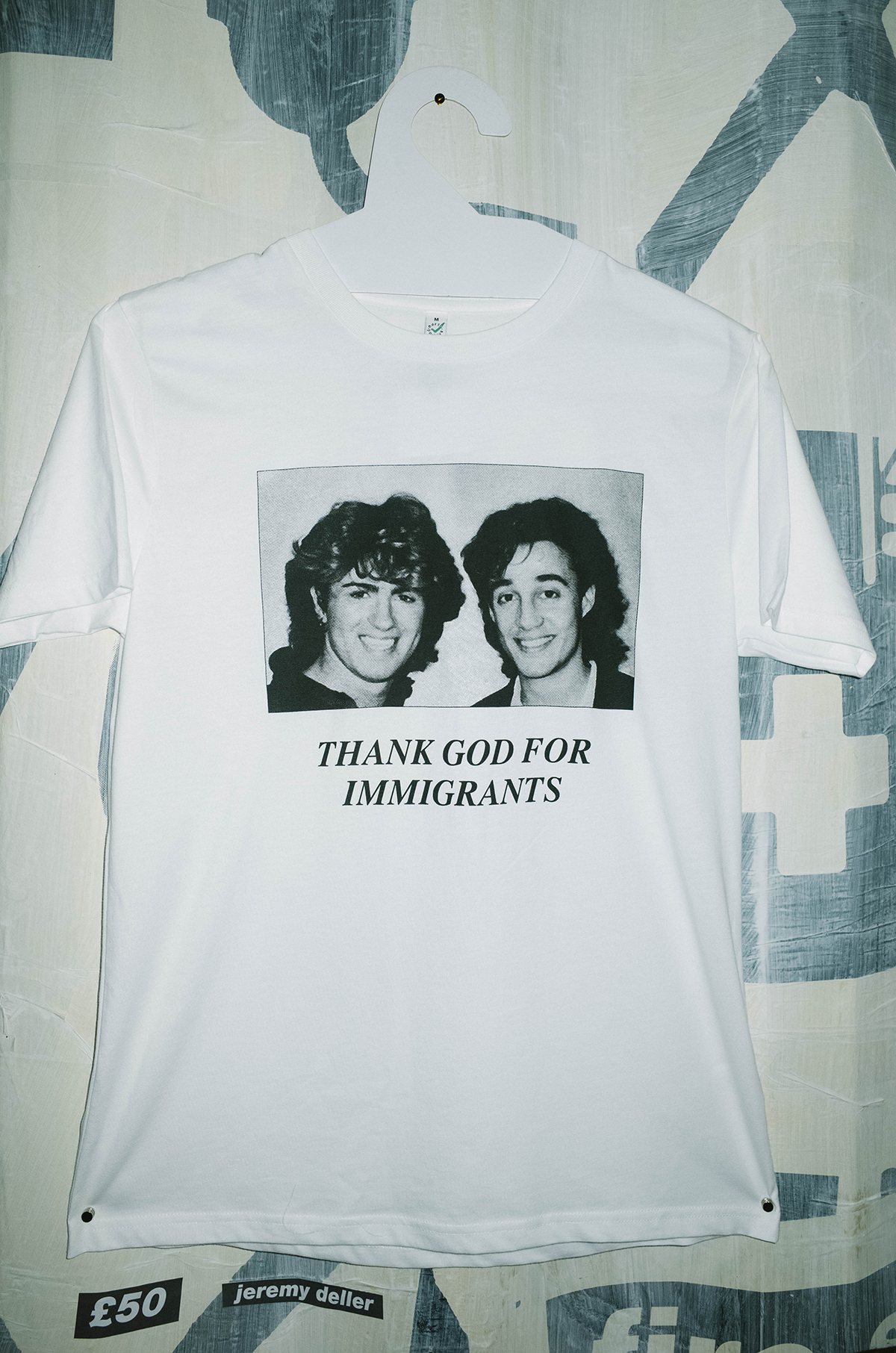

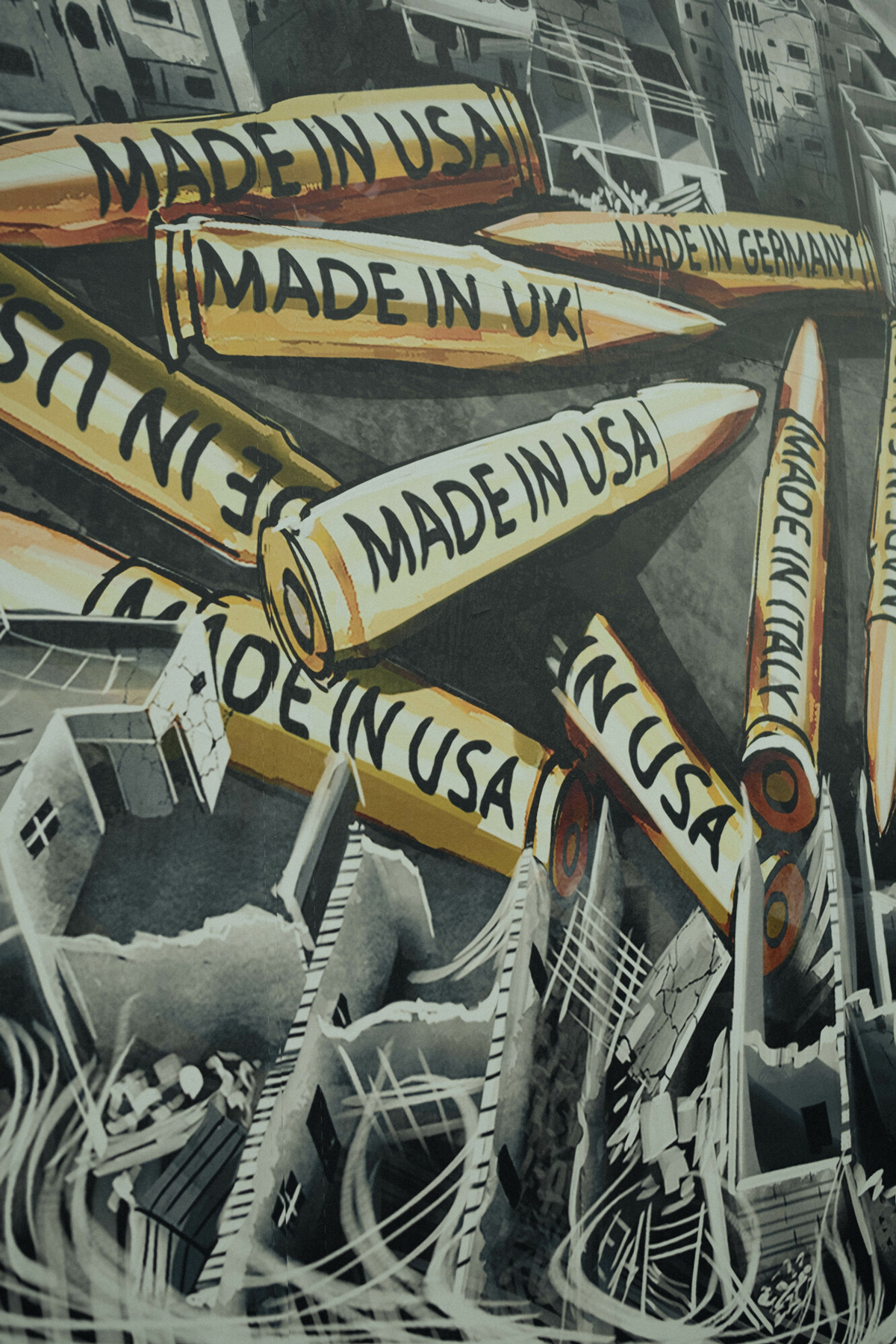

Integral to the event’s success was Kaye Dunnings, Creative Director of Glastonbury’s radical Shangri-La field, who brought her expertise in merging art and activism to the forefront. Her involvement went beyond curating a visual spectacle; she helped shape Act 1.5 into a climate rallying cry – using the streets of Bristol as a platform for celebrating activists, and a large-scale gallery of politically charged works at the event by artists like Kennard Phillipps, Darren Cullen, and Ella Baron. Working alongside Massive Attack and BUILDHOLLYWOOD, the team’s collaborative vision aimed to deliver a message as bold as it was necessary.

“There’s a history of street art in Bristol,” Kaye explains. “It’s part of the fabric of Bristol, and it’s always been political. It felt right to bring that energy into this event because that’s what Act 1.5 is—political, urgent, and deeply connected to the city.” Through installations scattered across the city and the festival grounds, the project connected Bristol’s rich history of rebellious art with the urgency of climate activism.

18.10.24

Words by