Partnerships

Hak Baker on Hakeem, the revealing documentary that was five years in the making

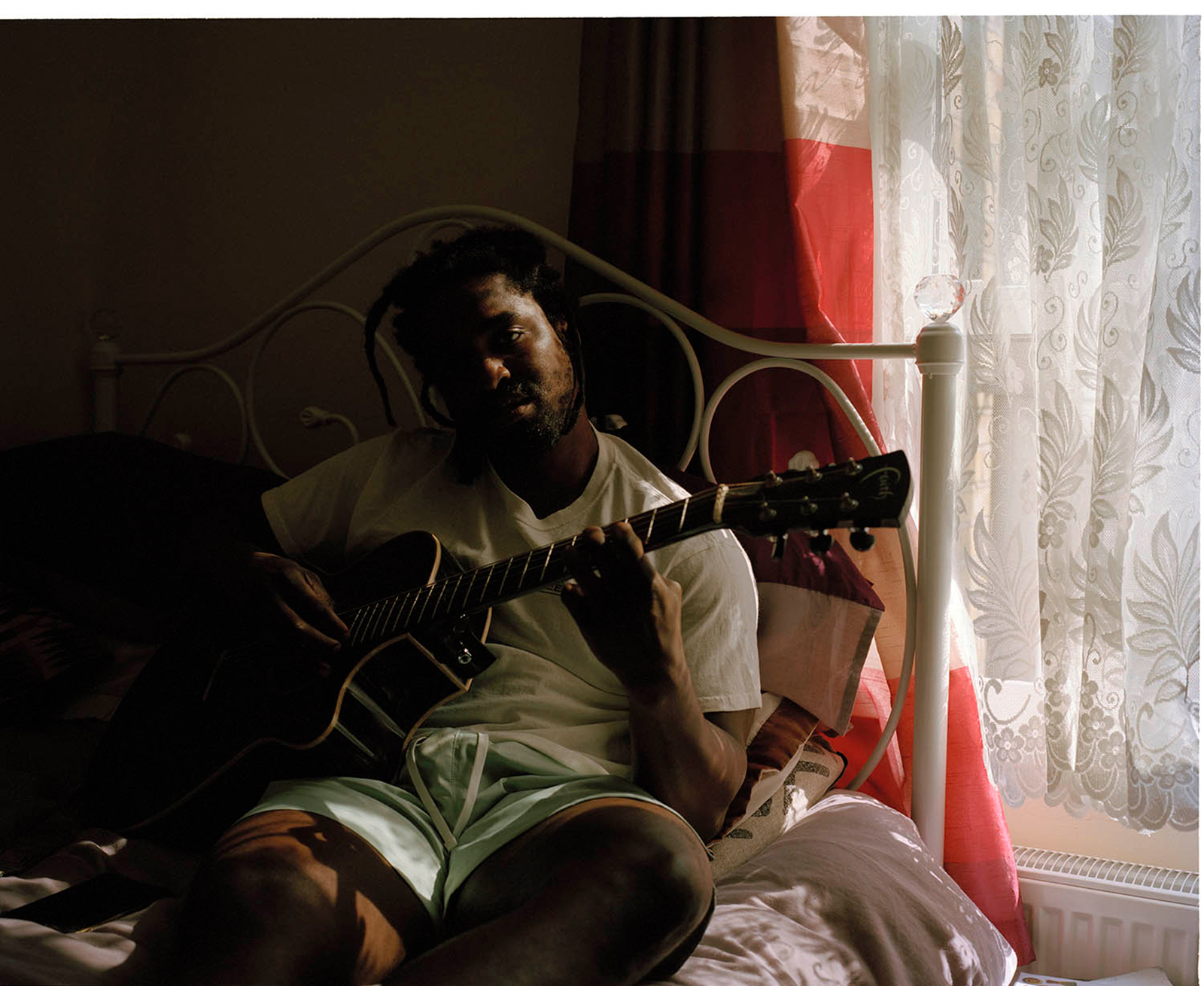

Hak Baker doesn’t hide much.

His music, brimming with raw honesty, has been his way of narrating life since the release of his 2017 EP Misfits. This project was a turning point for Baker, marking the first time he shared songs he’d written on the guitar—an instrument that had come into his possession after winning it in a prison raffle.

That guitar became a vessel for his evolution, helping him transition musically from a high-energy, Channel U-approved Grime MC in Bomb Squad, into the folk-inspired “G-folk” sound that Baker is now known for. His subsequent albums, Babylon (2020), Worlds End FM (2023) and more recently his latest EP Nostalgia Death (2024), have only solidified his presence as a musician who refuses to be boxed in. Each release has seen his sound become more layered, and more complex, but always anchored in storytelling—stories that only Hak can tell.

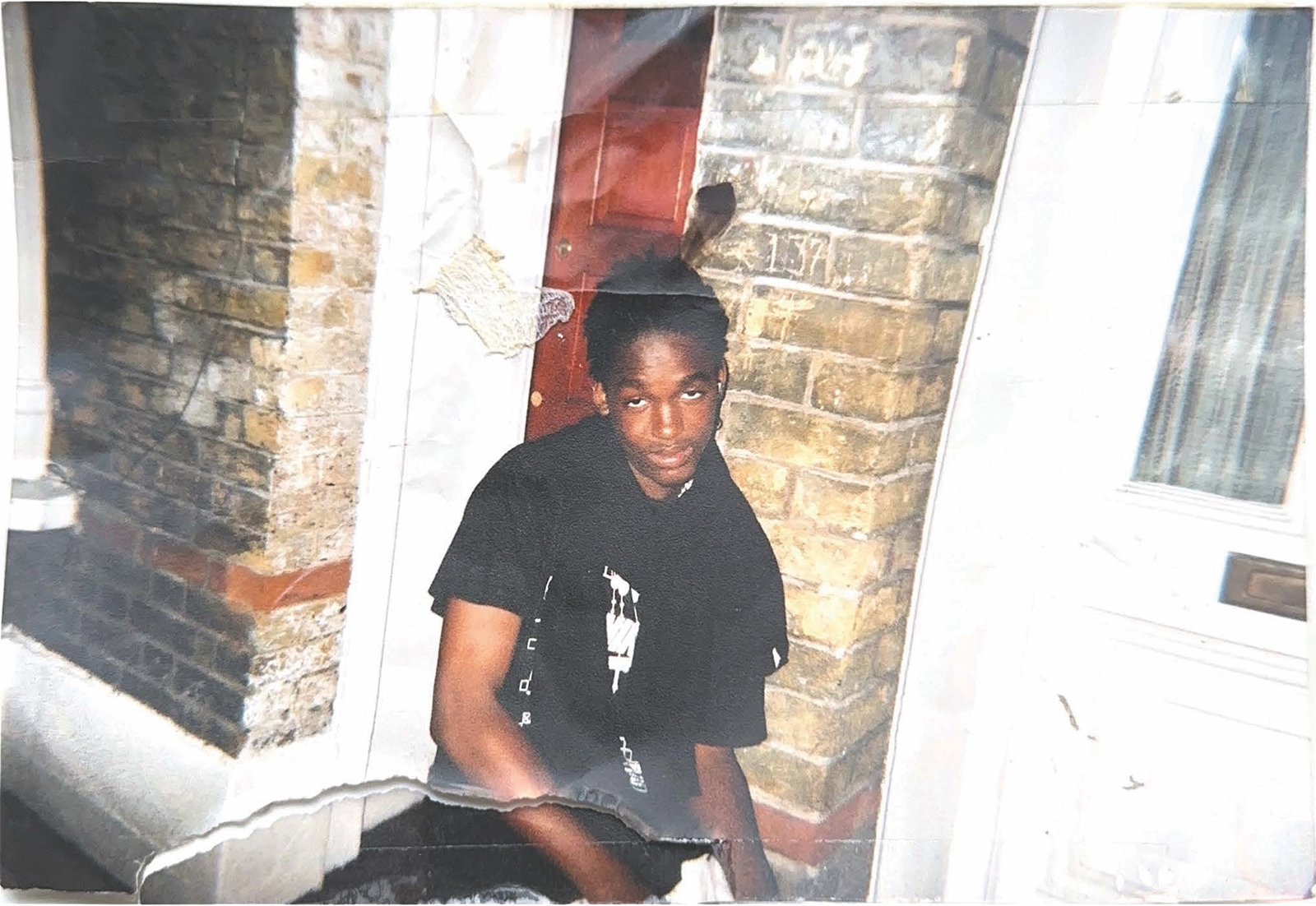

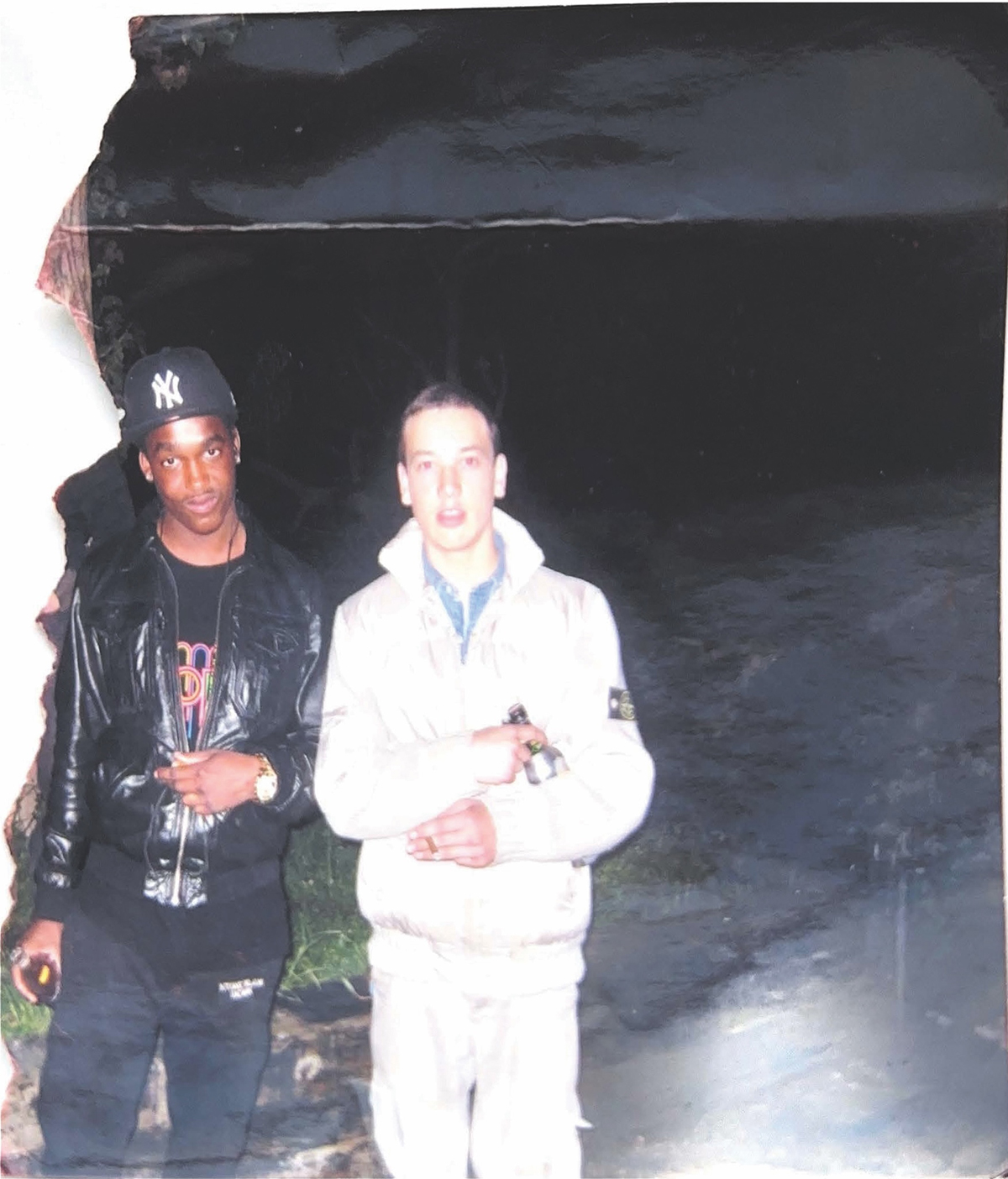

However, Baker’s most recent release with his name on isn’t music at all. It’s a film—Hakeem—an intensely personal documentary directed by James Topley and Ivo Beckett of DEADHORSES. The film was premiered at BUILDHOLLYWOOD’s event space The CarWash in the heart of Shoreditch, with an intimate screening and Q&A hosted by CassKid, during which, an emotional Hak Baker added further detail to what is already a close-up look at his life on and off stage.

21.10.24

Words by