Partnerships

In the trenches with music and documentary photographer Dennis Morris

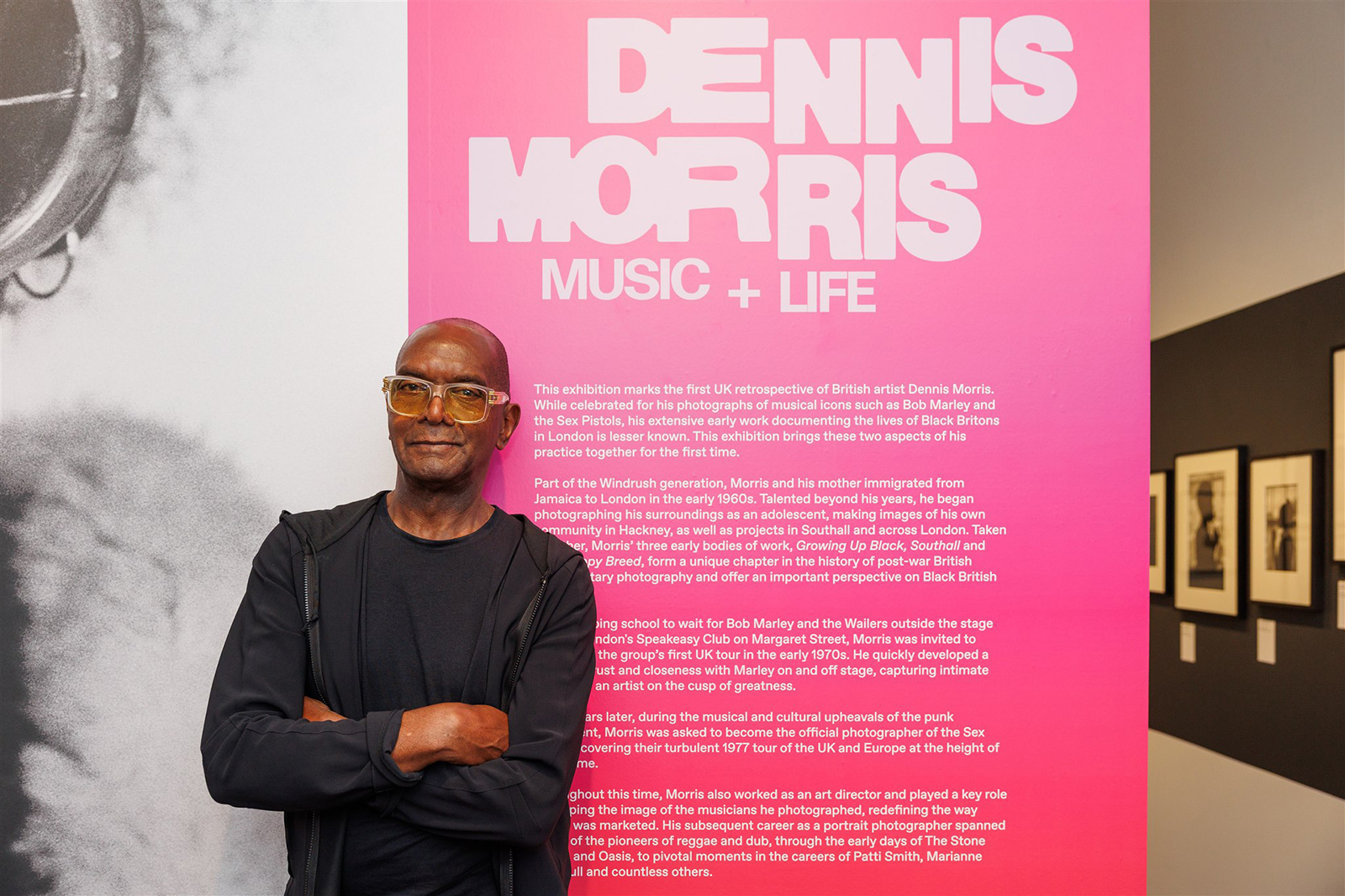

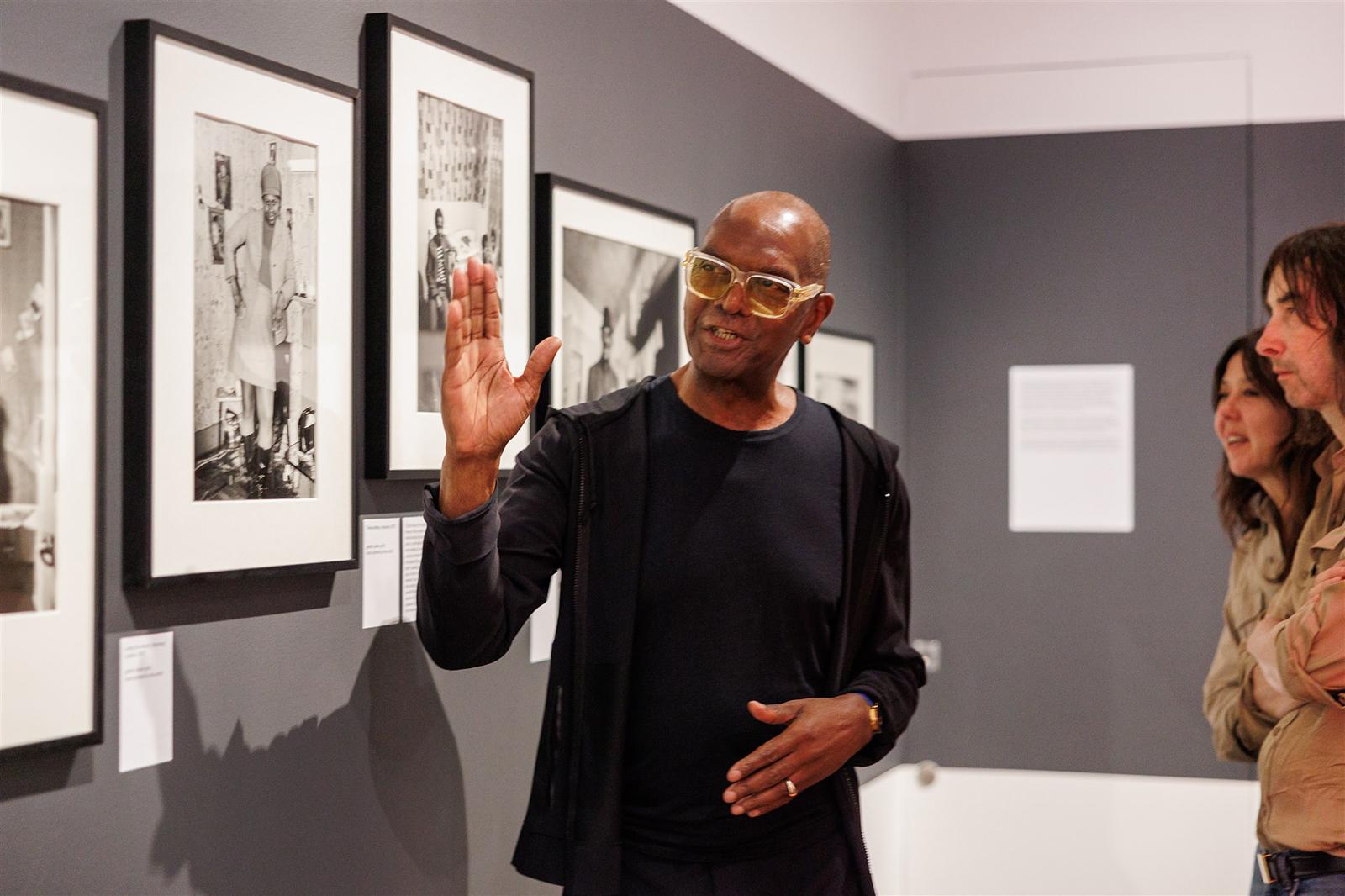

BUILDHOLLYWOOD has partnered with The Photographers’ Gallery to extend the gallery’s exhibition Dennis Morris: Music + Life into the streets of London. The prolific photographer talks about his unique relationship with Bob Marley, and why he looked to war reportage rather than music magazines for inspiration.

“Magic” is a word that comes up regularly with photographer Dennis Morris. He felt it when he saw a TV for the first time as a child, when he encountered a box in the corner of a room that he thought could hear him speak. He experienced it again when he saw an image printed from a negative for the very first time. There’s a sense of wonder in those early moments in his life that still seems visceral all these decades later. But when it comes to his own achievements, it was never magic; it was tenacity. It was all Morris’s doing.

Born in Kingston, Jamaica, Morris moved to London as a child, where he was introduced to photography at the tender age of nine. By the time he was a teenager, he had begun to forge a career in photography, producing timeless, instantly recognisable images of 1970s musicians such as Bob Marley, the Sex Pistols, and Marianne Faithfull, as well as later music acts like Oasis and Radiohead, which appeared on magazine covers and record sleeves. He also worked as a designer and an art director at Island Records.

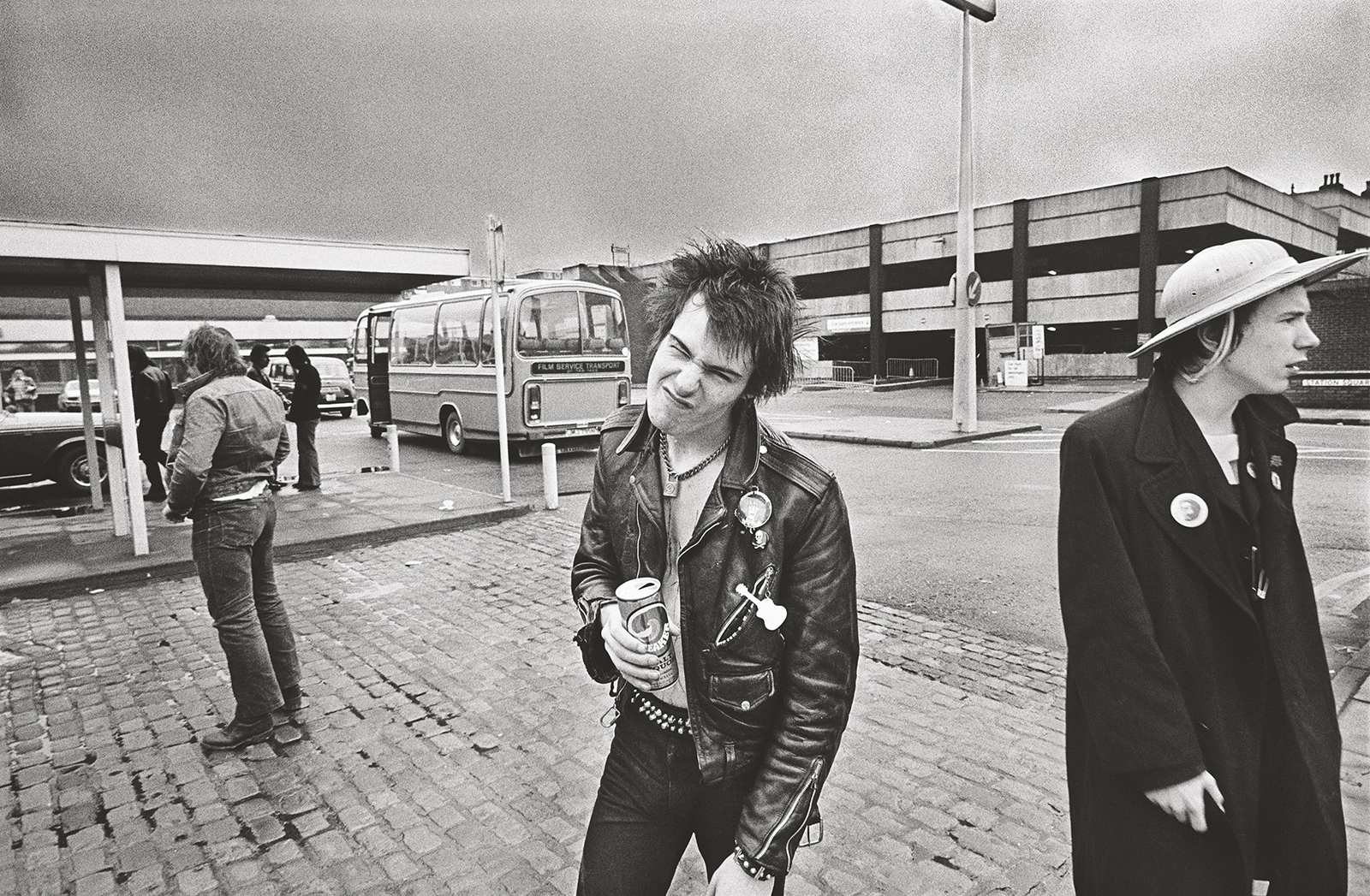

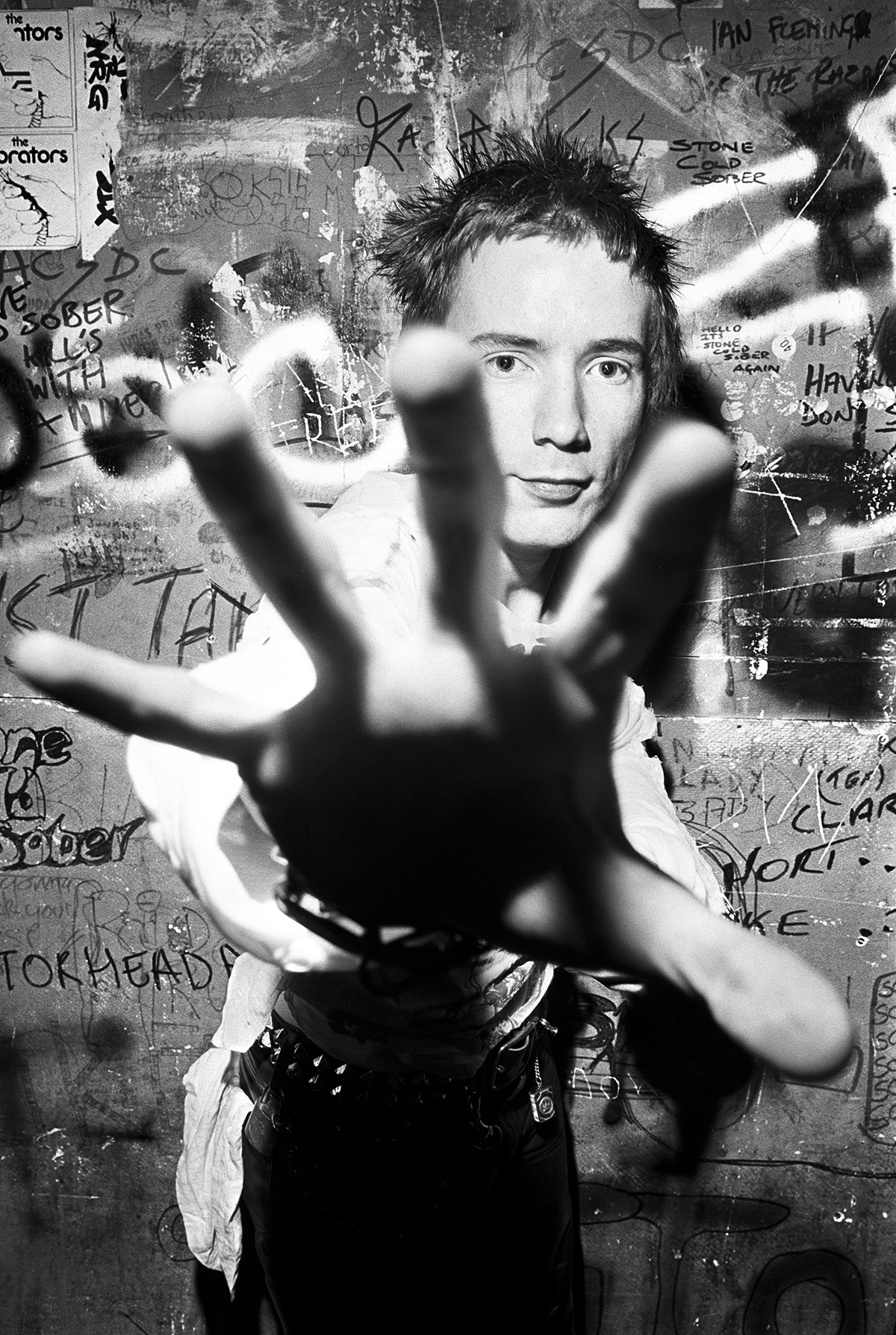

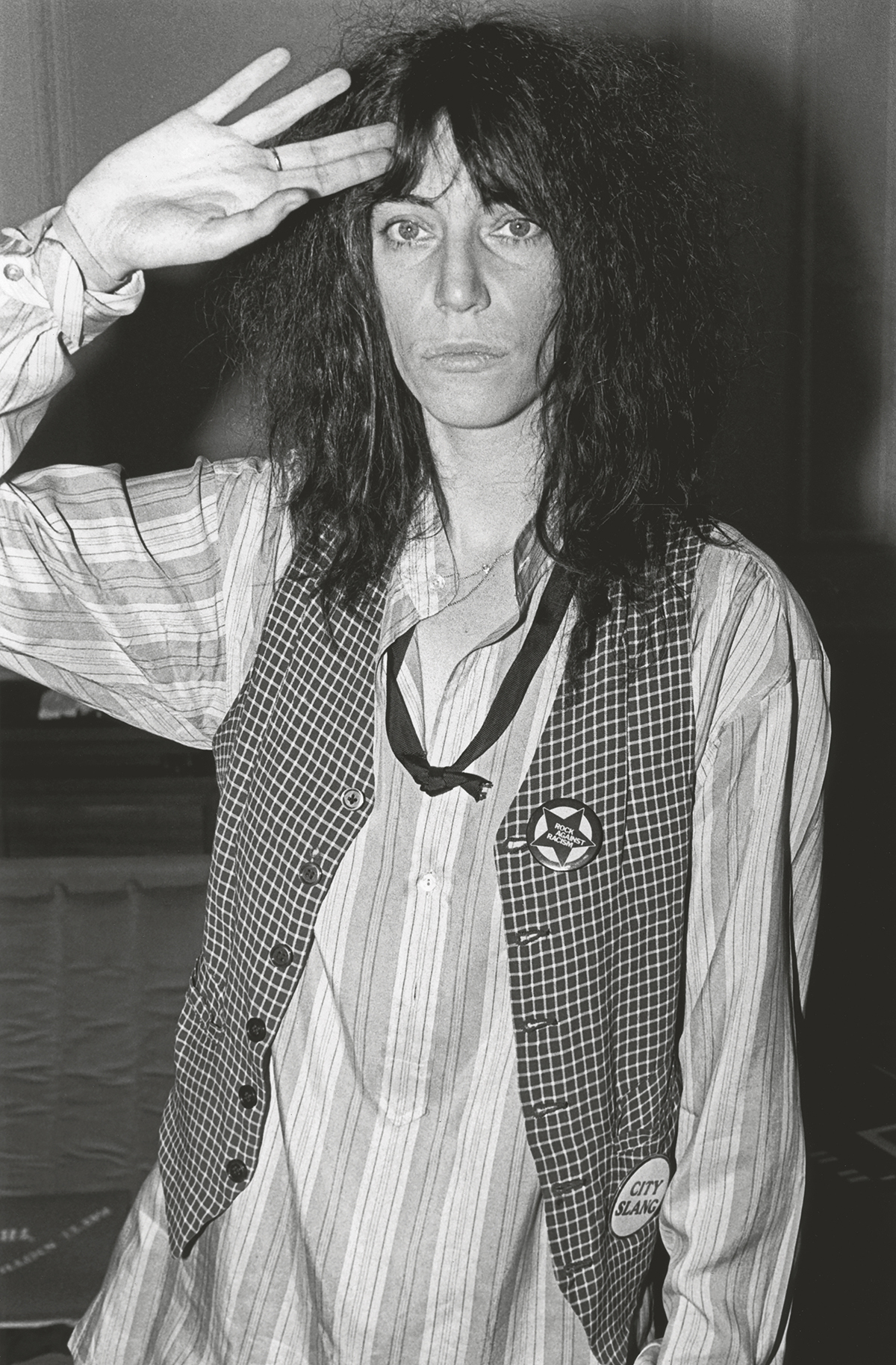

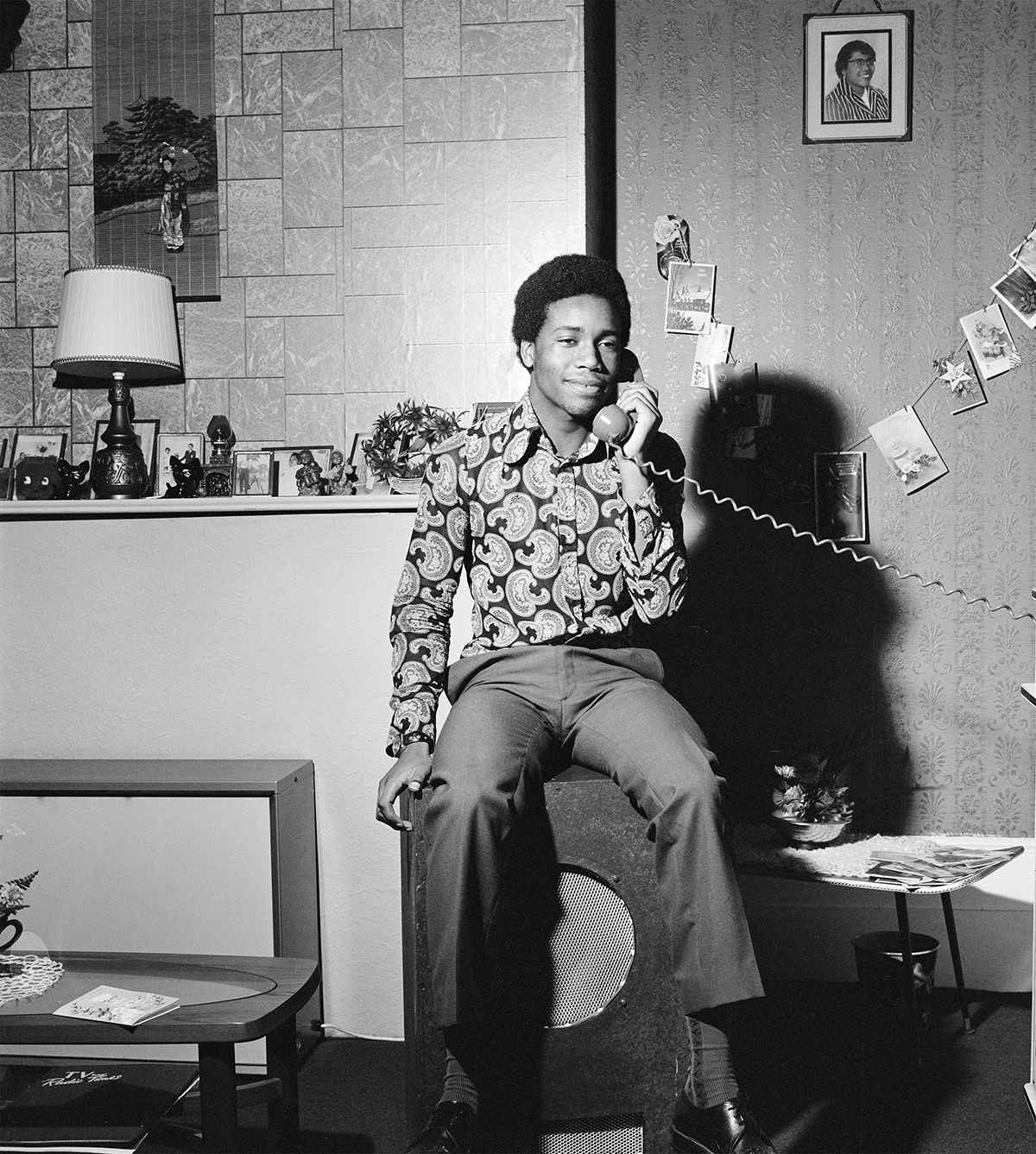

Many of his portraits show these musicians’ performative side: the pomp of the Pistols, the enigmatic drama of Marianne Faithfull. But his “fly on the wall” approach also uncovered their hidden depths – a pain or an uncertainty, perhaps. He has always wanted to show the three-dimensionality of people, a philosophy he also applied to his photographs of everyday people going about life, whether in his project documenting Black British life in Hackney, his intimate series made in Southall’s Sikh communities, or his poignant photographs taken when returning to Kingston.

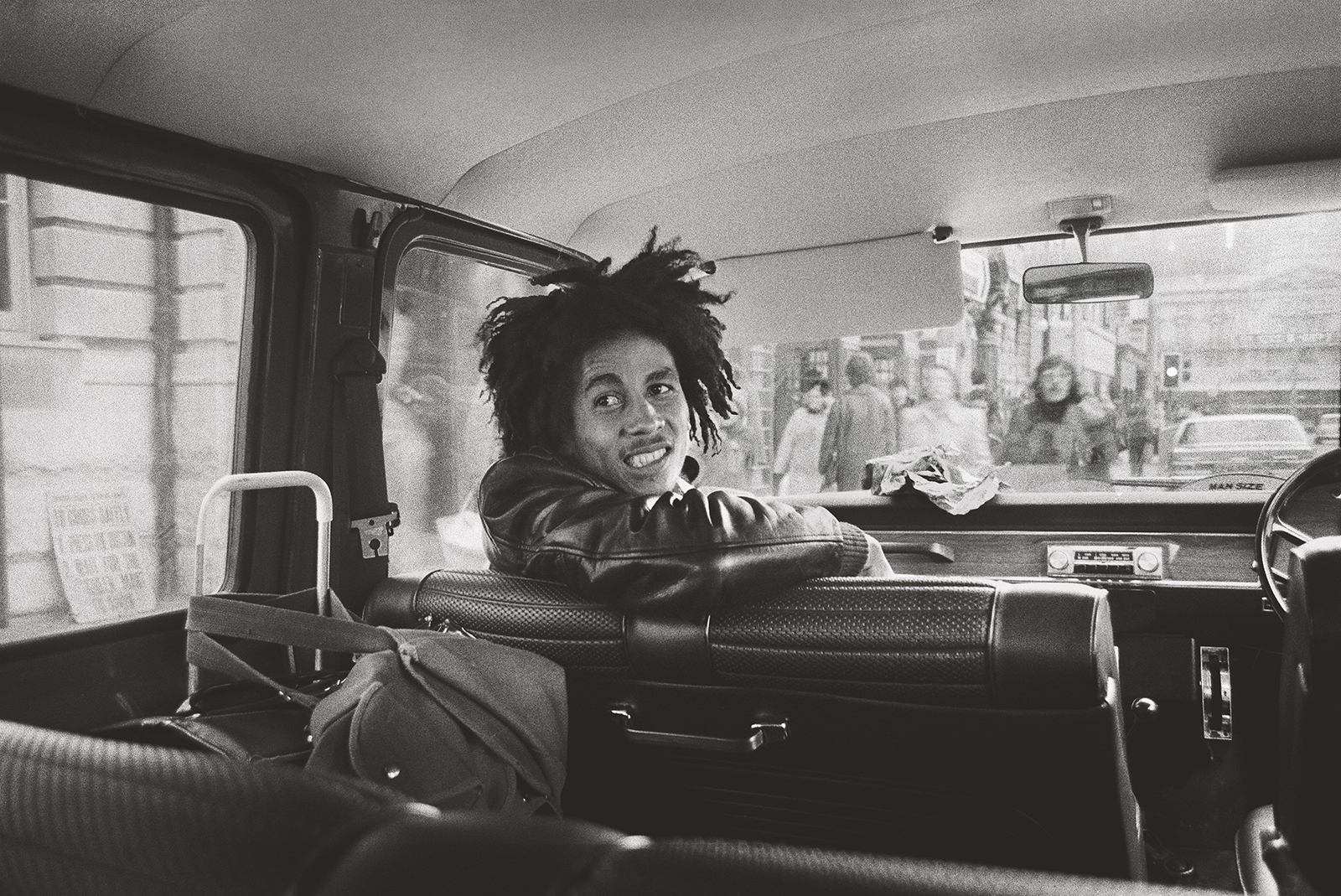

First image: Babylon by van, London, 1973 © Dennis Morris

22.08.25

Words by

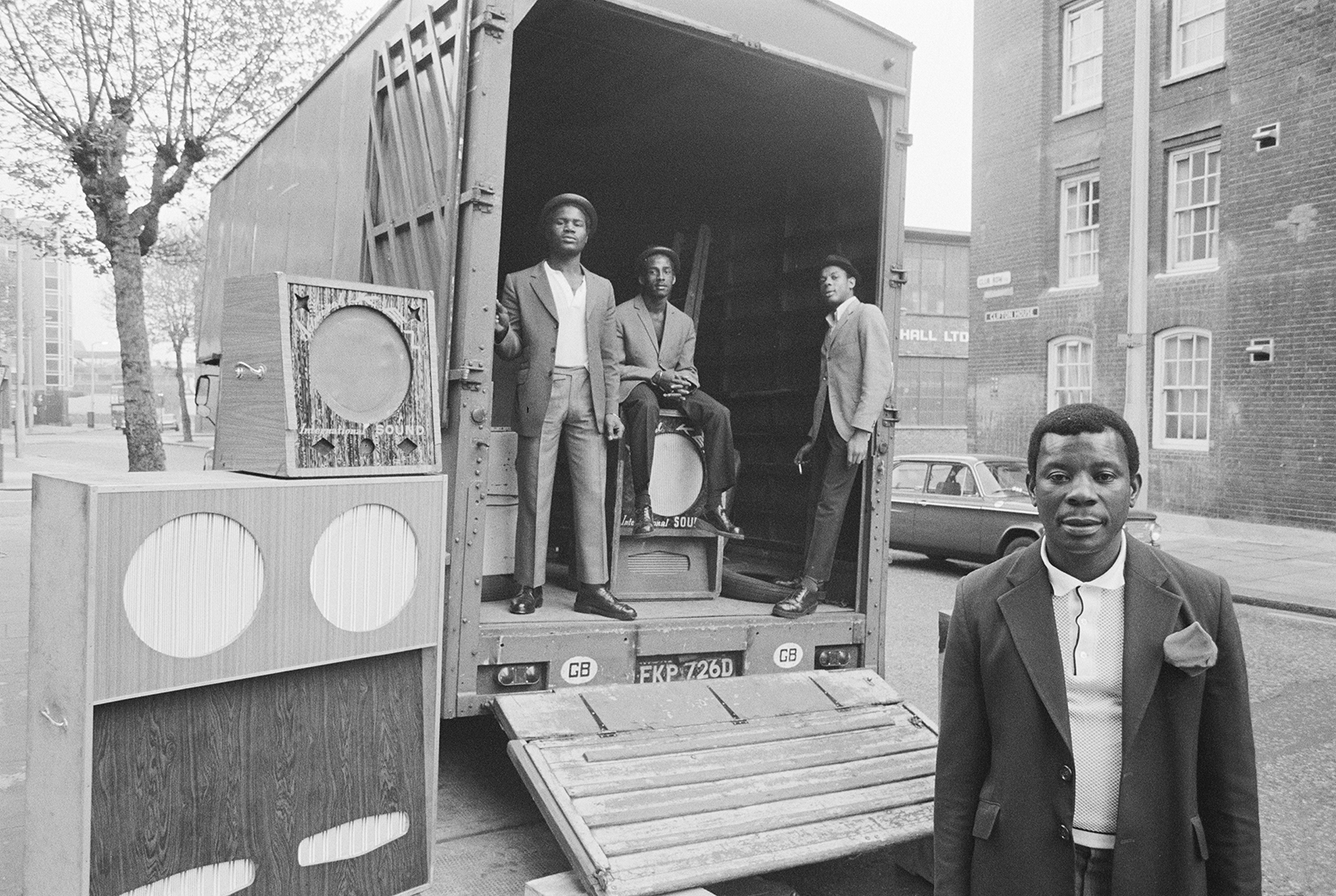

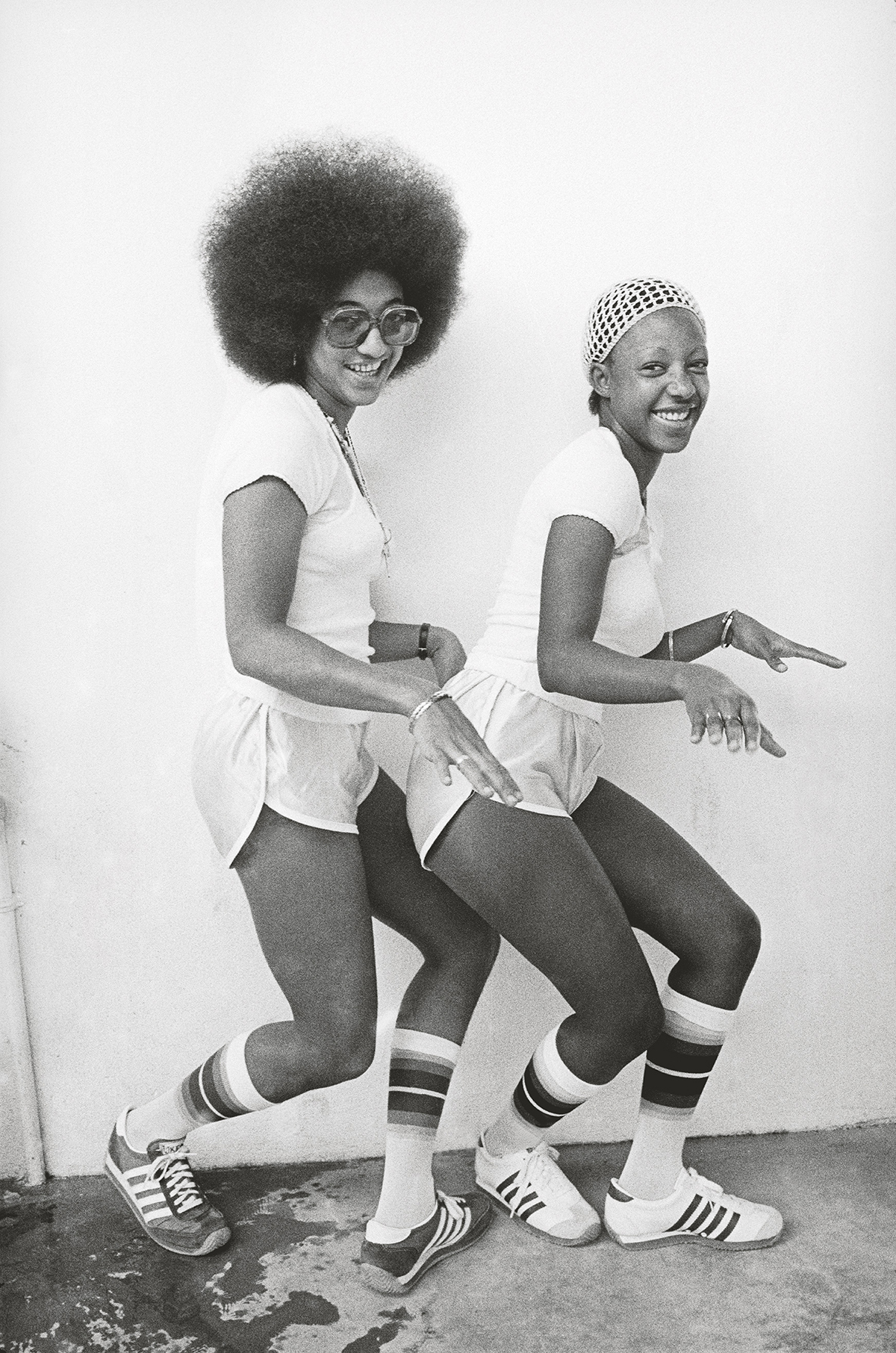

Admiral Ken with Bix Men, Hackney, London, 1973 © Dennis Morris

Admiral Ken with Bix Men, Hackney, London, 1973 © Dennis Morris

Southall streets, 1976 © Dennis Morris

Southall streets, 1976 © Dennis Morris

Man with his two daughters and his most prized possession, Southall, 1976 © Dennis Morris

Man with his two daughters and his most prized possession, Southall, 1976 © Dennis Morris

Lyceum Theatre, London, July 1975 © Dennis Morris

Lyceum Theatre, London, July 1975 © Dennis Morris

Shopping for the Trenchtown kids, Leeds, UK, 1974 © Dennis Morris

Shopping for the Trenchtown kids, Leeds, UK, 1974 © Dennis Morris

Burning, 1973 © Dennis Morris

Burning, 1973 © Dennis Morris

Sid Vicious and Johnny Rotten, S.P.O.T.S tour, Coventry bus station, UK, 1977 © Dennis Morris

Sid Vicious and Johnny Rotten, S.P.O.T.S tour, Coventry bus station, UK, 1977 © Dennis Morris

Johnny Rotten, backstage at the Marquee Club, London, 23 July 1977 © Dennis Morris

Johnny Rotten, backstage at the Marquee Club, London, 23 July 1977 © Dennis Morris

Patti Smith during the promotional tour for Horses, London, 1976 © Dennis Morris

Patti Smith during the promotional tour for Horses, London, 1976 © Dennis Morris

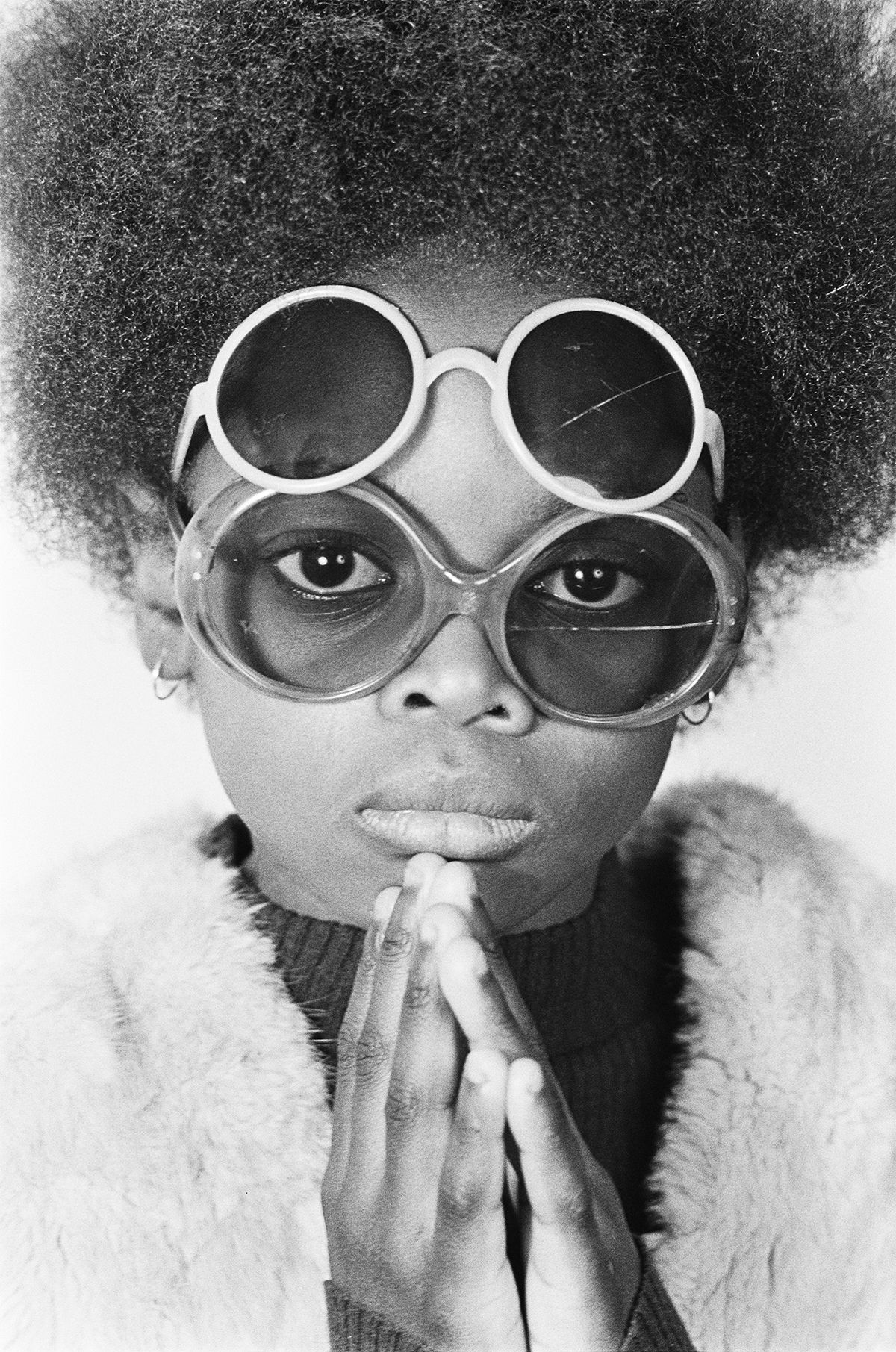

‘Living the Dream’, Hackney, London, 1973 © Dennis Morris

‘Living the Dream’, Hackney, London, 1973 © Dennis Morris

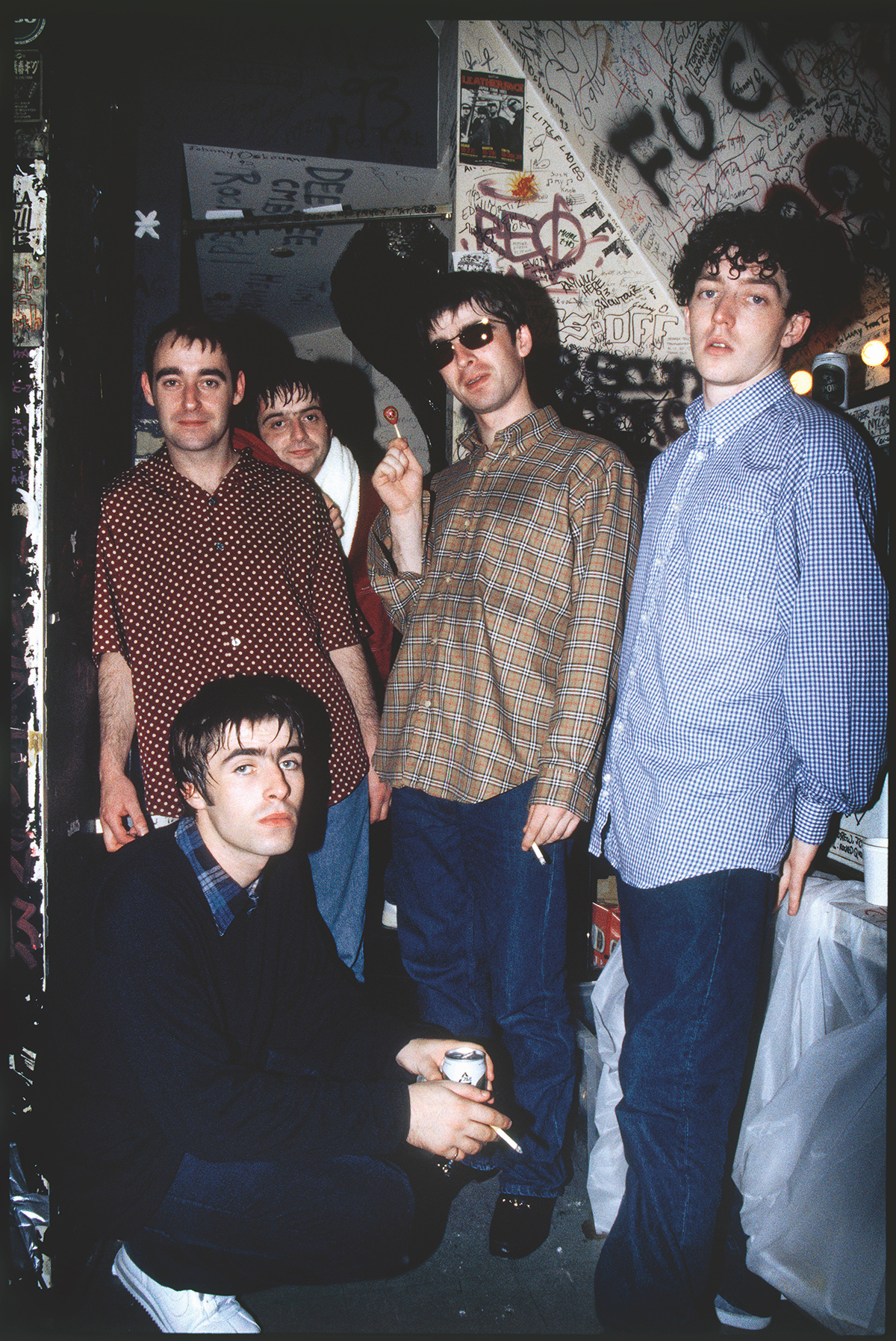

Original Oasis lineup, Japan, 1994 © Dennis Morris

Original Oasis lineup, Japan, 1994 © Dennis Morris

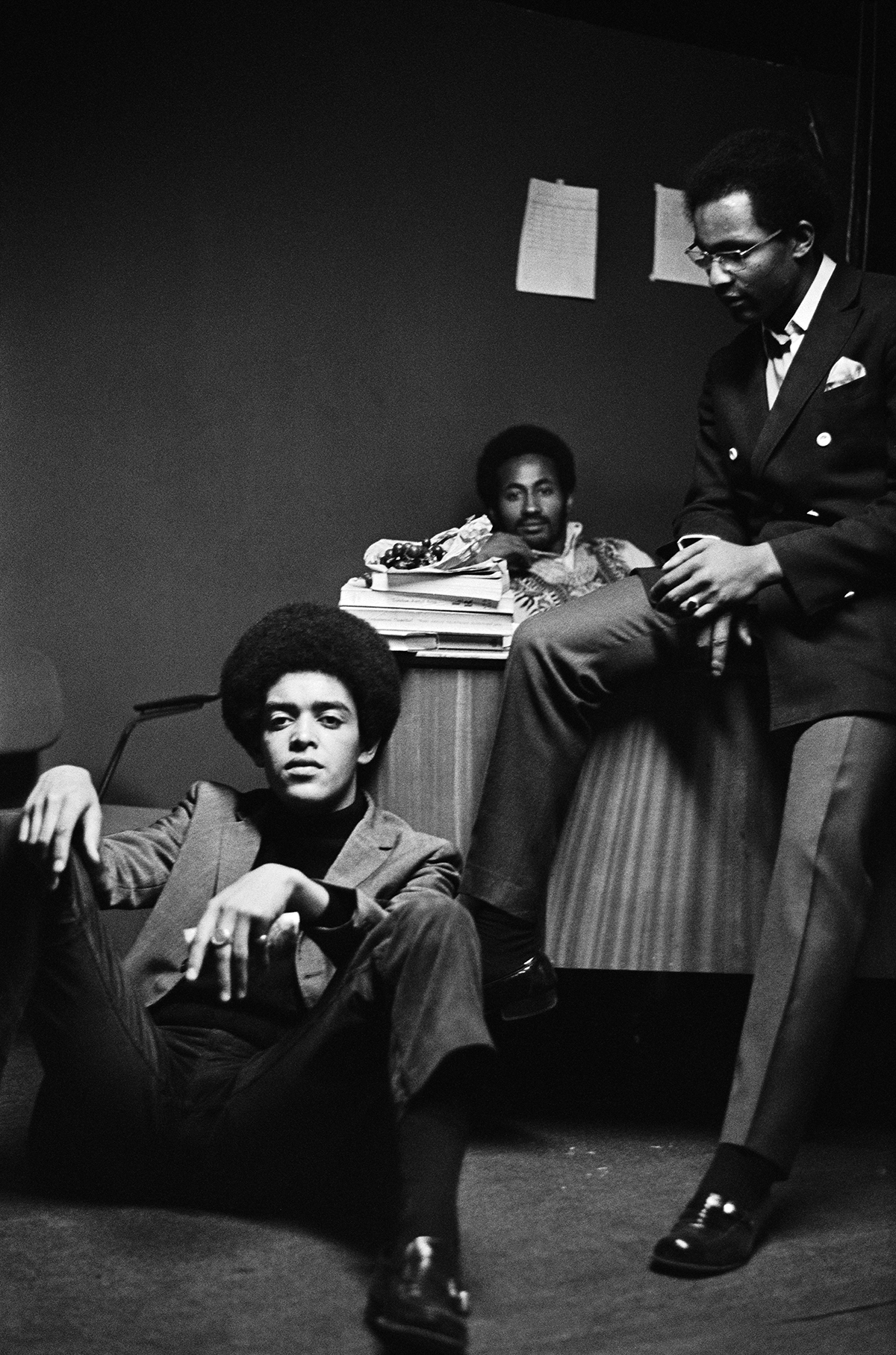

The Brothers, The Black House, Islington, London, 1970 © Dennis Morris

The Brothers, The Black House, Islington, London, 1970 © Dennis Morris