Your Space Or Mine

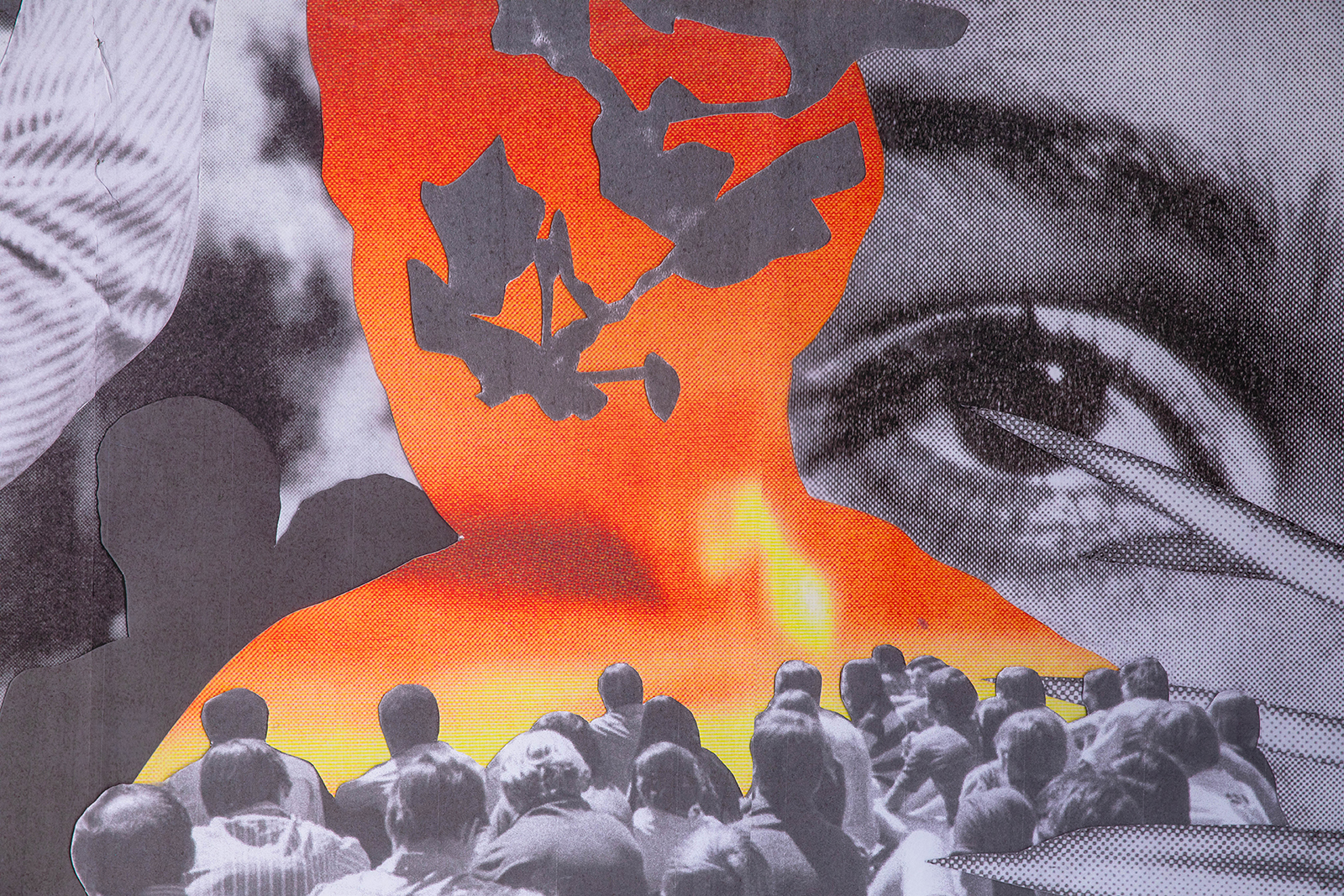

Witness this: An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind

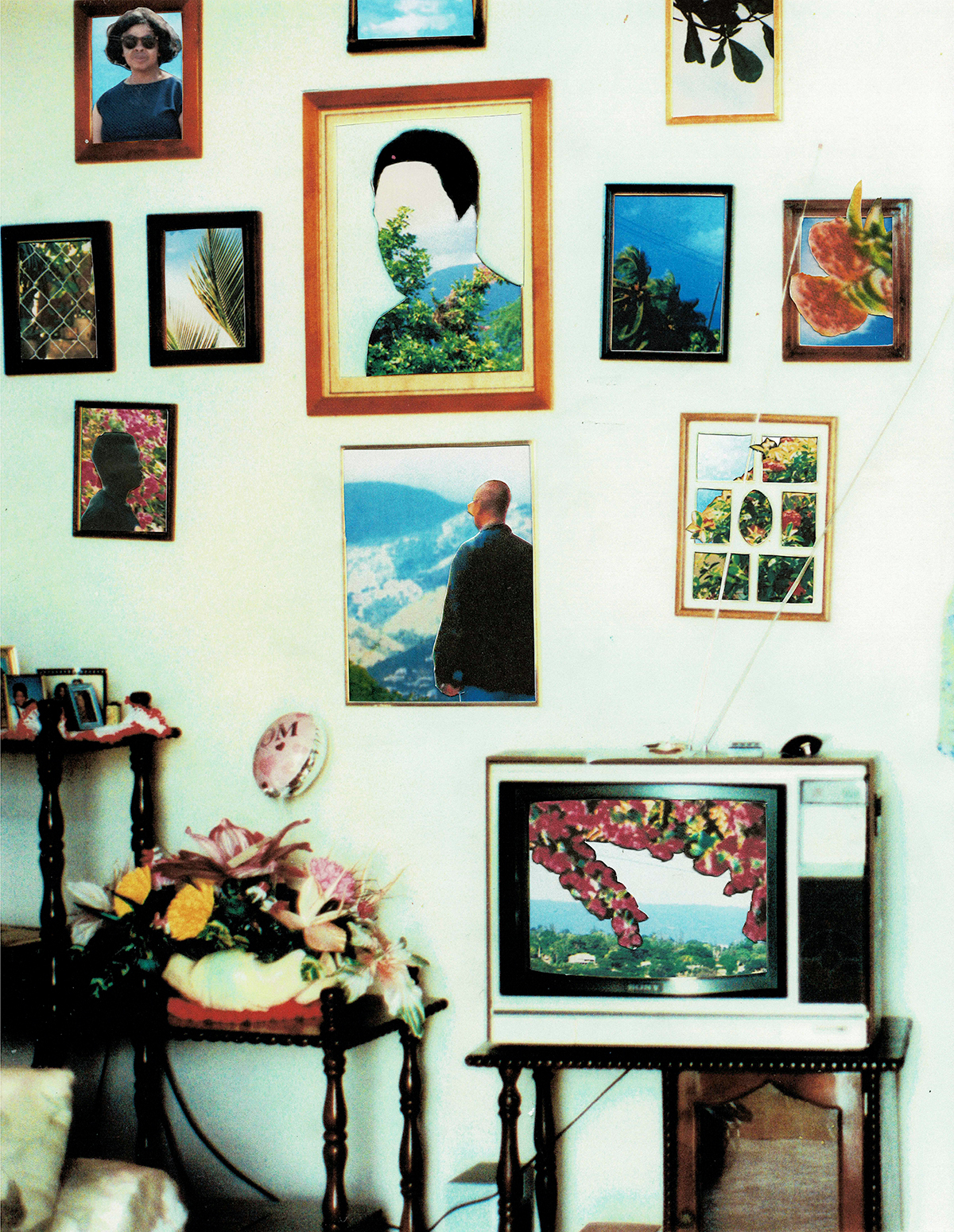

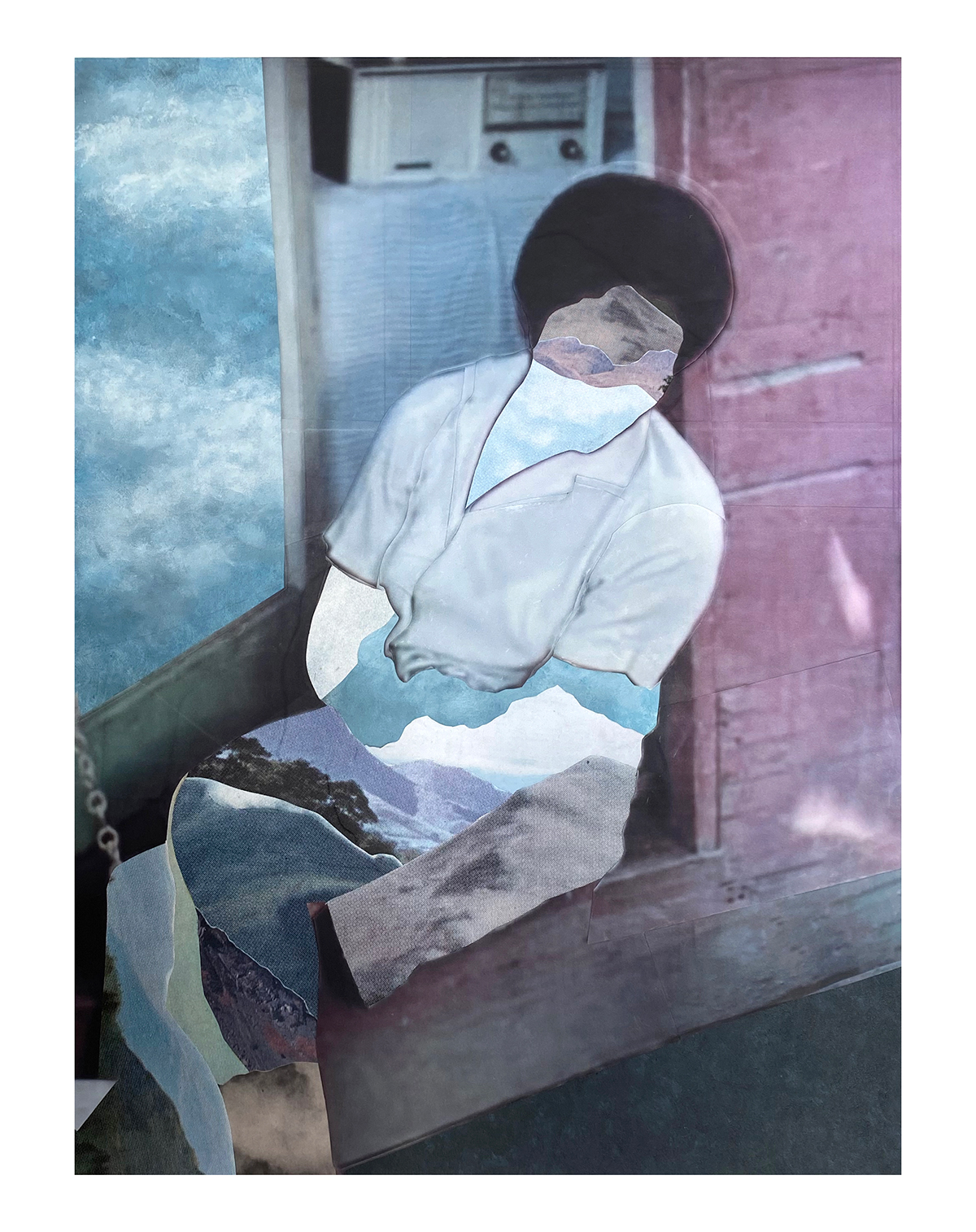

Visual artist Jazz Grant’s new narrative collage series for BUILDHOLLYWOOD’s Your Space Or Mine transforms billboards across the capital into portals of protest, turning passive witnessing into a powerful visual reckoning. As we remain held in a chokehold by digital screens that feed us tragedy interspersed by quaint matcha lattes, Jazz Grant zooms in on the bleak incongruity staring us straight in the face.

The heat is rising, the clock is ticking, the feed is reloading. Our devices are an extension of our limbs now – benign digital growths, still attached by lithe, fleshy tendrils to our febrile, stubby digits. We are tethered to them, pacified by them, and beguiled by them. And yet, despite our tacit sinking into their enchanting 4G catchment, there remains hope: that these screens are also on our side – informing us, educating us, and offering access and agency to challenge more potent powers. This is the paradox that Jazz Grant’s new work confronts – a visceral, multi-part billboard series exploring what it means to witness a world in collapse, and still find a way to respond.

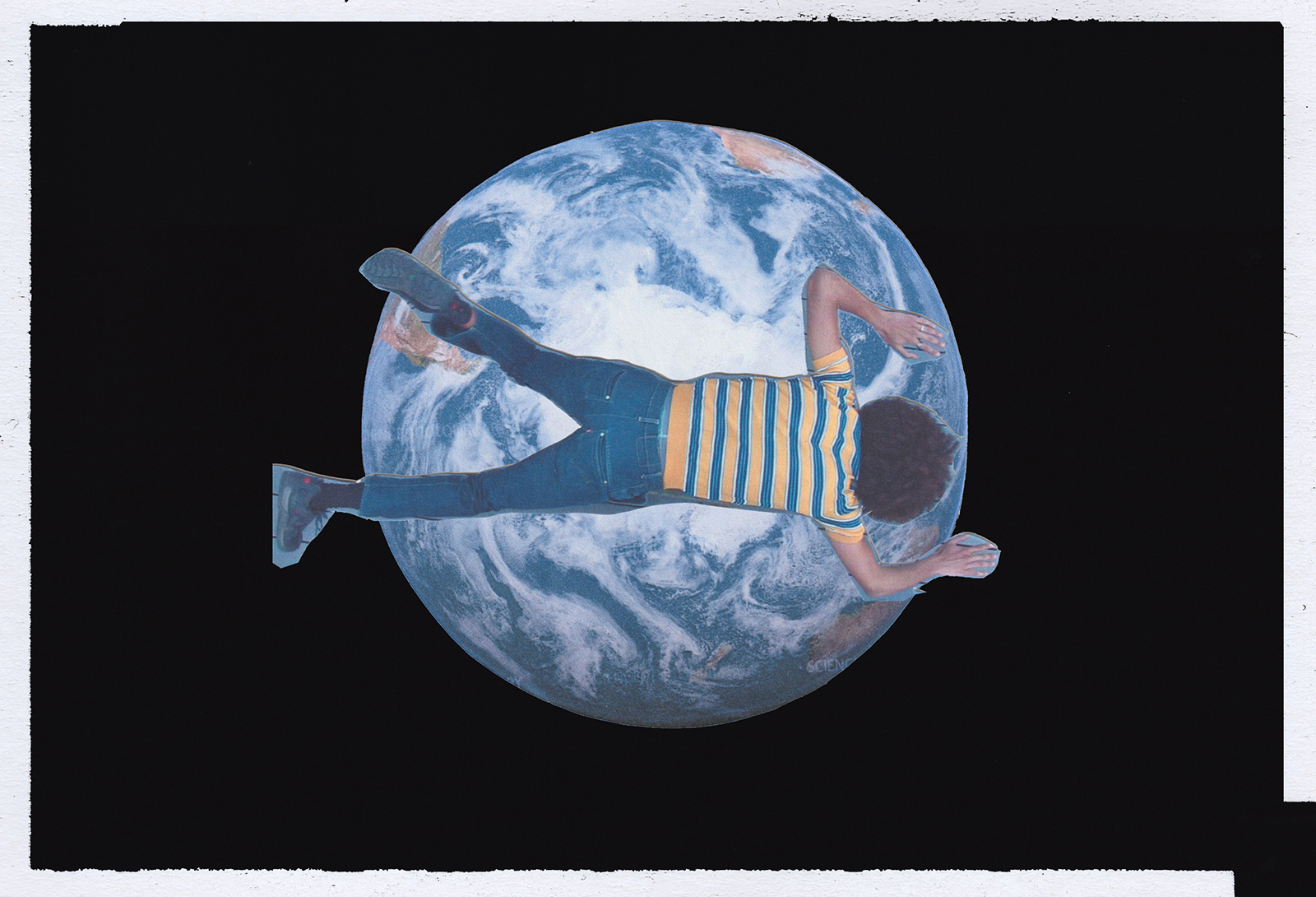

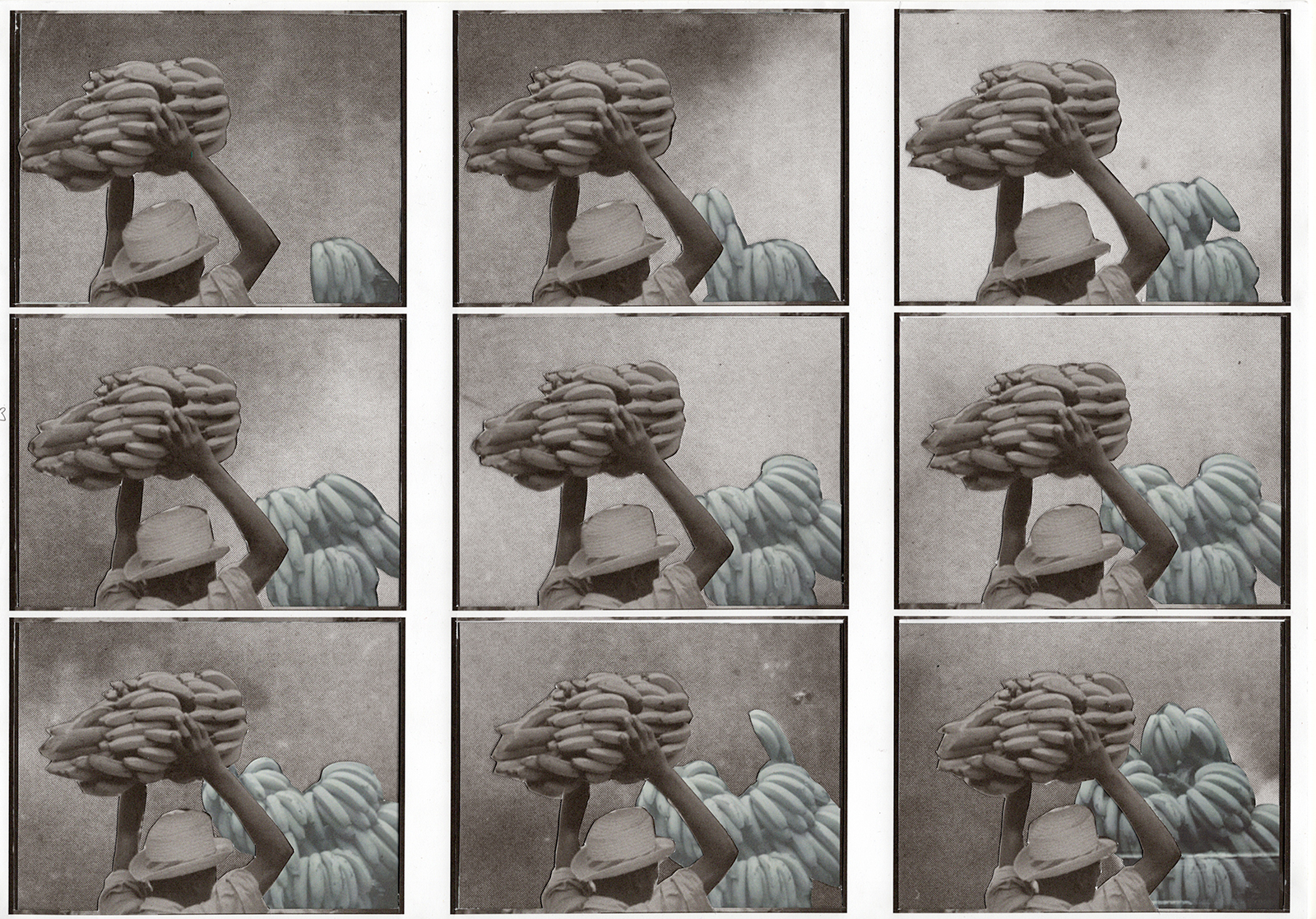

Known for her emotionally charged collage and stop-motion animation, Jazz Grant’s practice is grounded in instinct, texture, and storytelling. Her current billboard takeover spans London and unfolds in four acts, from eyes burning with fire to silhouettes locked in protest, it captures a narrative arc of grief, rage, and ultimately, resistance. “I was really aware of how much I’ve been observing the burning world, both metaphorically and literally burning on my phone,” she says. “Then I made the connection that the billboards themselves almost look like a phone screen”.

01.07.25

Words by