Of course, we’re not the first to experience this sort of profound difference in our day-to-day. Daniel Dafoe, in his ‘Journal of the Plague Year’ (1722), wrote about the shift in ambience bought about by once crowded pavements suddenly being abandoned, that ‘profound silence in the streets’. Such an abrupt switch in our prevailing assumptions about space and place remind us that we’re not so in control of our material environment as we perhaps thought. This begs the question whether and to what extent our environments control us. And being faced with such a mismatch between expectations and a new physical reality leads us to wonder if we might also be subject to metaphysical influences.

Whilst the term predated Sigmund Freud’s 1919 essay ‘Das Unheimliche’ (‘The Uncanny’) it was the pioneer of psychoanalysis who popularised an understanding of the word and phenomena as eerie, mysterious, being beyond what is normal and expected, a suggestion of something supernatural. In Freud’s terms the uncanny is the experience of a return to something formerly repressed. Something which ought to have remained hidden has come to light.

Philosophy Professor Lucy Huskinson writes about Freud’s attempt, ‘to map the ‘corridors’ and ‘recesses’ of the mind in analogous manner to an urban geographer who surveys the physical and social terrains of towns and cities’. This reveals important features of the places we use and inhabit, ‘not least, places that have become uncanny.’ Huskinson also cites Freud’s illustration of the uncanny as akin to his being in an unfamiliar Italian town and trying to leave but every route he tries brings him back to the same street he started from. The uncanny has a double nature, both familiar and not, bewitching and repellent. To experience a feeling of the uncanny in the city is to introduce us, however fleetingly, to that city’s alter ego.

Discoveries at the ancient Sumerian city of Girsu – located in modern day southern Iraq – include the first evidence of cuneiform writing, administrative records, the concept of timekeeping, etc. That is, the planned city is and always has been a site and symbol of control. Arguably our contemporary metropolises with their gridded layout; unforgiving materials: stone, tarmac, concrete, steel and glass; all the more and less hidden boundaries or markers which seek to determine behaviours… It is an axiomatic truth of architectural design and urbanism that the city equates to the rational, the logical. But that’s not the whole story by any means.

In ‘Real Cities’ (2005) Steve Pile, Professor of Human Geography, makes the case for taking more seriously the human imaginary, fantasmatic and emotional aspects of city life, to admit the possibility of metaphysical moment in our urban experience. Whilst neuroscience is unlocking the material basis of thought, wondering and – together with psychology – wonderment, it’s a fair bet to say there will always be a further step to take, all cannot be explained in terms of physical matter alone.

In the process of mapping urban experience and consciousness there are bound to be margins of doubt, an equivalent to, ‘Beyond this point there be monsters!’ When it comes to exploring ‘how we dwell in the city and how the city dwells in us’ it would seem to be a productive cast of mind to adopt a view, if only temporarily, that admits we share our work and residential spaces, the streets, squares, shopping malls, parks, transport systems, etc., with at least the possibility of uncanny encounters.

Regarding experiences in the city that don’t make sense, that can’t be satisfactorily accounted for by reason, there was a period when I repeatedly gashed my forehead walking into the same tree on the same street for months on end. The road was pretty anonymous, no shops, rarely any people around, so few distractions. Maybe I’m prone to daydreaming but it happened too often, at all times of day and night, in all weathers, walking alone and in company I collided with the same thorn sharp branch. If this sounds ridiculous another example of the uncanny Freud puts forward is his repeatedly walking into the same piece of furniture when entering a room. Uncanny places frustrate our expectations and stymie our intentions. As Lucy Huskinson notes, in doing so they appear to be playing a game with us, the undisclosed rules of which we are not party to.

Beyond my weird arboreal collisions there are less tangible presences. In his ‘Some Cities’ (1996) Victor Burgin – an artist and writer who, judging by the rigour and precision of his prose, you’d think wouldn’t have much truck with the supernatural – notes that in 1993, by the old port area of Marseille, ‘An enormous pit was excavated, its cliff like walls striated with centuries of occupation. […] In the deepest layer, workers found the largely intact skeleton of a Phoenician ship.’ In Burgin’s cool, clipped but none the less evocative account of people in cities and cities in people, a porosity of sorts is alluded to. It’s definitely there in the photographs that accompany the text. Being reminded that under our feet lies the debris resulting from human agency and natural turmoil colours our being in the city.

It’s not just the revelation of hidden vessels, submerged materiality that might ‘talk’ to us. Burgin’s photograph taken in old Marseille, of an empty street is placed opposite a deadpan description of the German army and French police action that saw the former inhabitants of this neighbourhood heading for the death camps. An empty street is never mute.

One day when I was twelve my form teacher, Mr. S., alerted the class to the flickering but never entirely dimmed presence of absence. In the context of reminding us to take responsibility for our actions he told a personal story. A heart-breaking tale of a seventeen-year-old lad who one day casually couldn’t be bothered to post a letter so asked his sweetheart to do it for him. She was blown to pieces, killed outright by a falling bomb. Mr. S. never married or had children. He said he never asked anyone to do anything for him that he couldn’t as easily do for himself. And in class that morning, however many years later it was, he said it still wasn’t possible for him to walk past a post box without seeing her. Steve Pile calls this the grief-work of city life.

The dead can return, and hang around, in seemingly innocent ways – in memorials and commemorative rituals, in cemeteries and hospitals, in the names of buildings and streets, in personal acts of memory for those who have gone before. As many have observed, the city is a place of memory: of memories on top of memories, even of memories of memories. To repeat acts of remembrance for some events, while forgetting or exorcising others, is a mark of what – and who – haunts us.

The uncanny is said to be the return of a forgotten experience without memory of its original content. Our cities then could be said to consist of both conscious and unconscious collisions between physical space and the human mind.

And it’s not a simple binary but a multiple pile-up. Juhani Pallasmaa wrote about our experience of space and memory in The Eyes of the Skin (1996):

We have an innate capacity for remembering and imagining places. Perception, memory and imagination are in constant interaction; the domain of presence fuses into images of memory and fantasy. We keep constructing an immense city of evocation and remembrance, and all the cities we have visited are precincts in this metropolis of the mind.

I live in a part of London that is part public pissoir, part scenic viewpoint. The foreshore, Deptford is a place where three great historical ages collide: mercantile, industrial and information. One day all those centuries simply disappeared. I looked out of my single sash window and saw… Nothing. Less than twenty feet away the river view was lost to an all enveloping fog. Its colonising presence as much felt as seen, a cold fume over the windowsill cleaving to the back of my skull. And the hollow, piercing, electro-metallic warning beep of the water bus echoes in endless grey. Exceptional changes in weather can induce a sense of the uncanny.

More prosaically a couple of weeks ago a high street in Hackney was closed due to a fragile building. The whole road in front of it was filled with a huge lattice of scaffolding. When the supporting structure first went up both pedestrian and vehicular traffic was detoured. The novelty of the public all having to take an alternative and unfamiliar route seemed to engender a mundane sense of wonder, a feeling that everyone was noticing others more than they would have had they been on their usual traverse down the main street. It made me think of artist Doris Salcedo’s work where she stacked fifteen hundred chairs to block a gap between two buildings. Inducing a sense of the uncanny is Salcedo’s métier.

For example, her 2007 Shibboleth Tate turbine hall installation, a 167-metre crack in the floor of a venue we thought we knew, threw our experience of space and place into anxious tumult. There’s a positive aspect to this disorientation though. In Shibboleth we’re alerted to the plight of ignored peoples, excluded histories. A new ‘room’ has been added to our house of experience. Likewise, whatever its multiple triggers, each instance of uncanny dislocation alerts us to something hitherto lost, suddenly recovered.

Artist Biog.

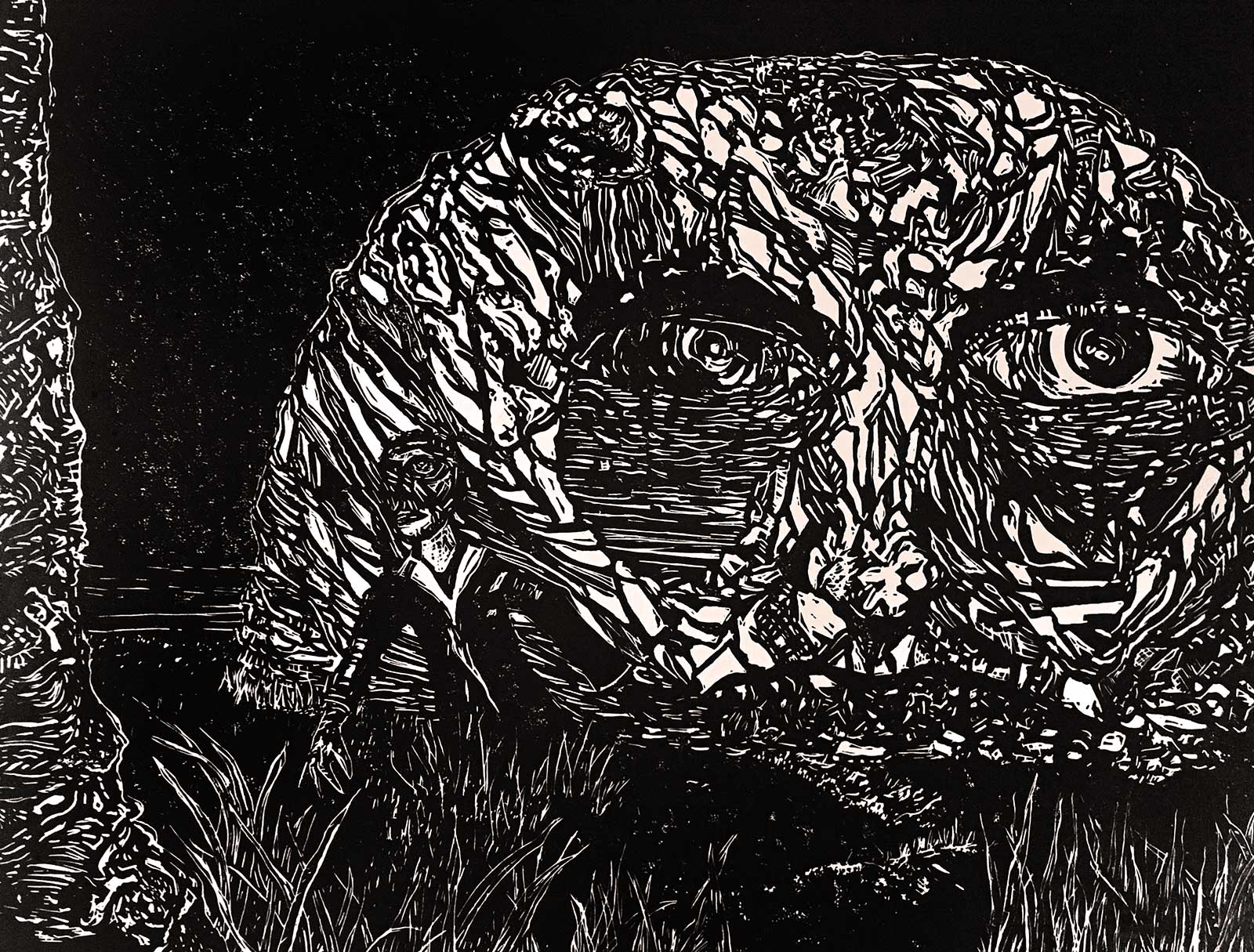

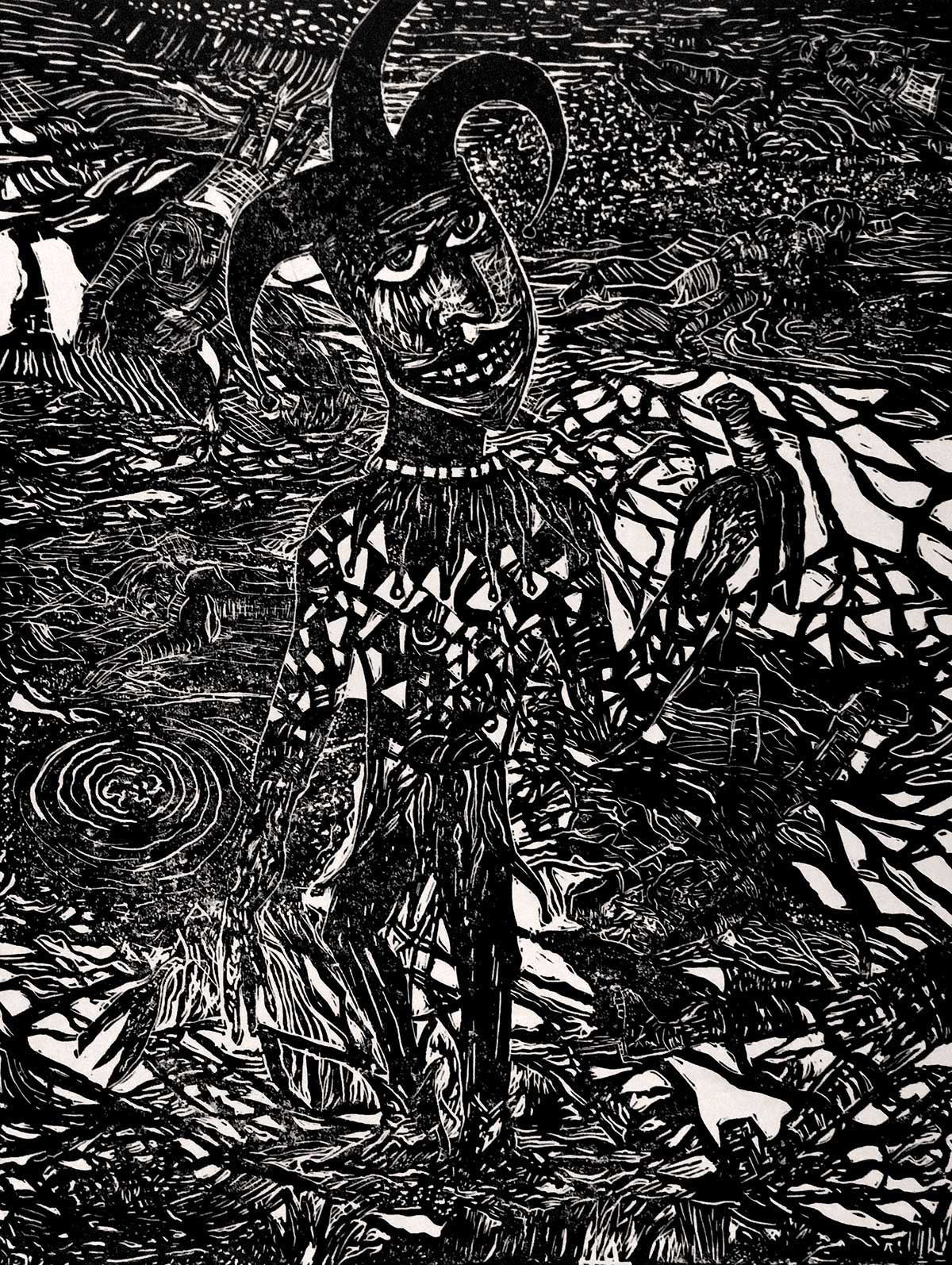

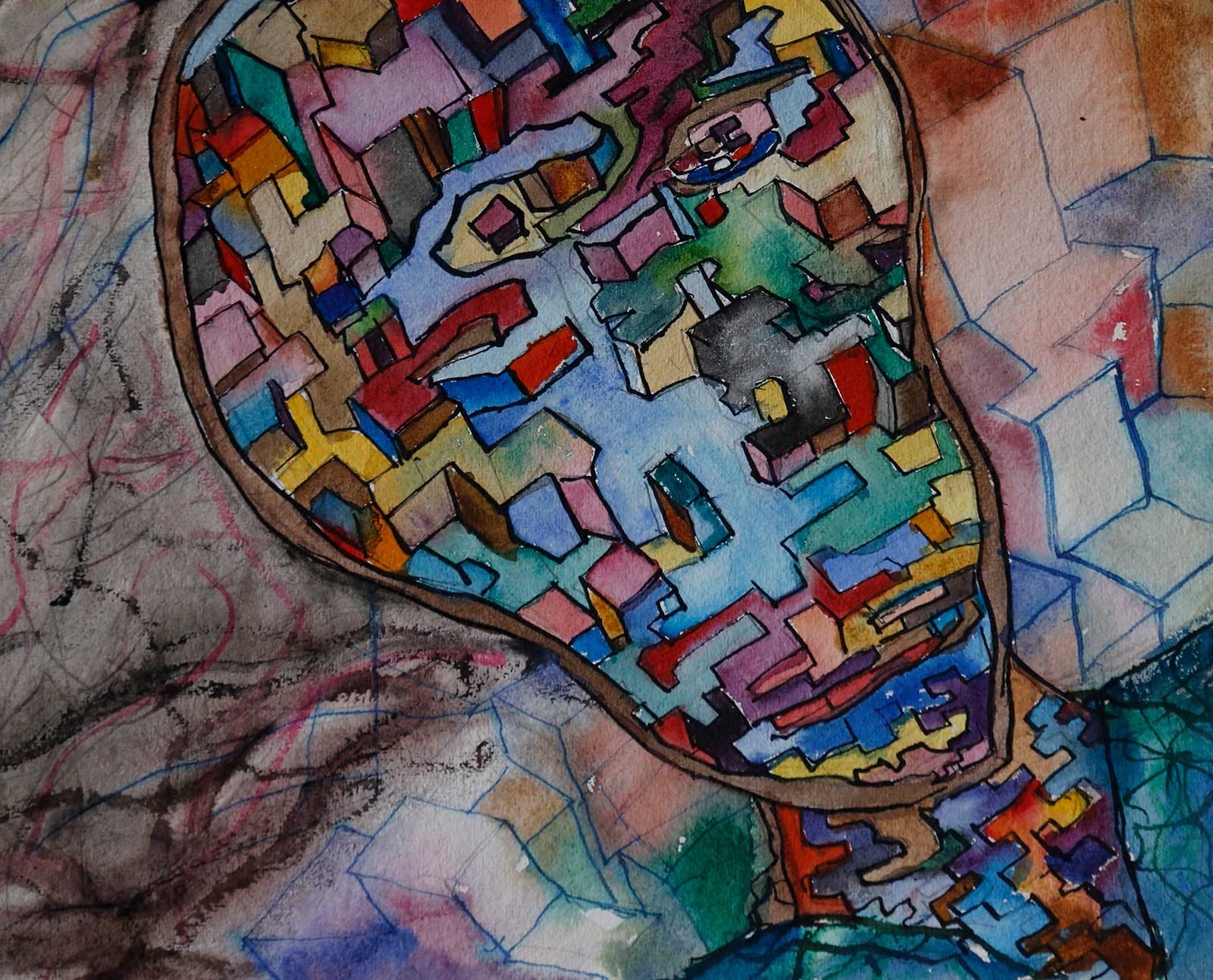

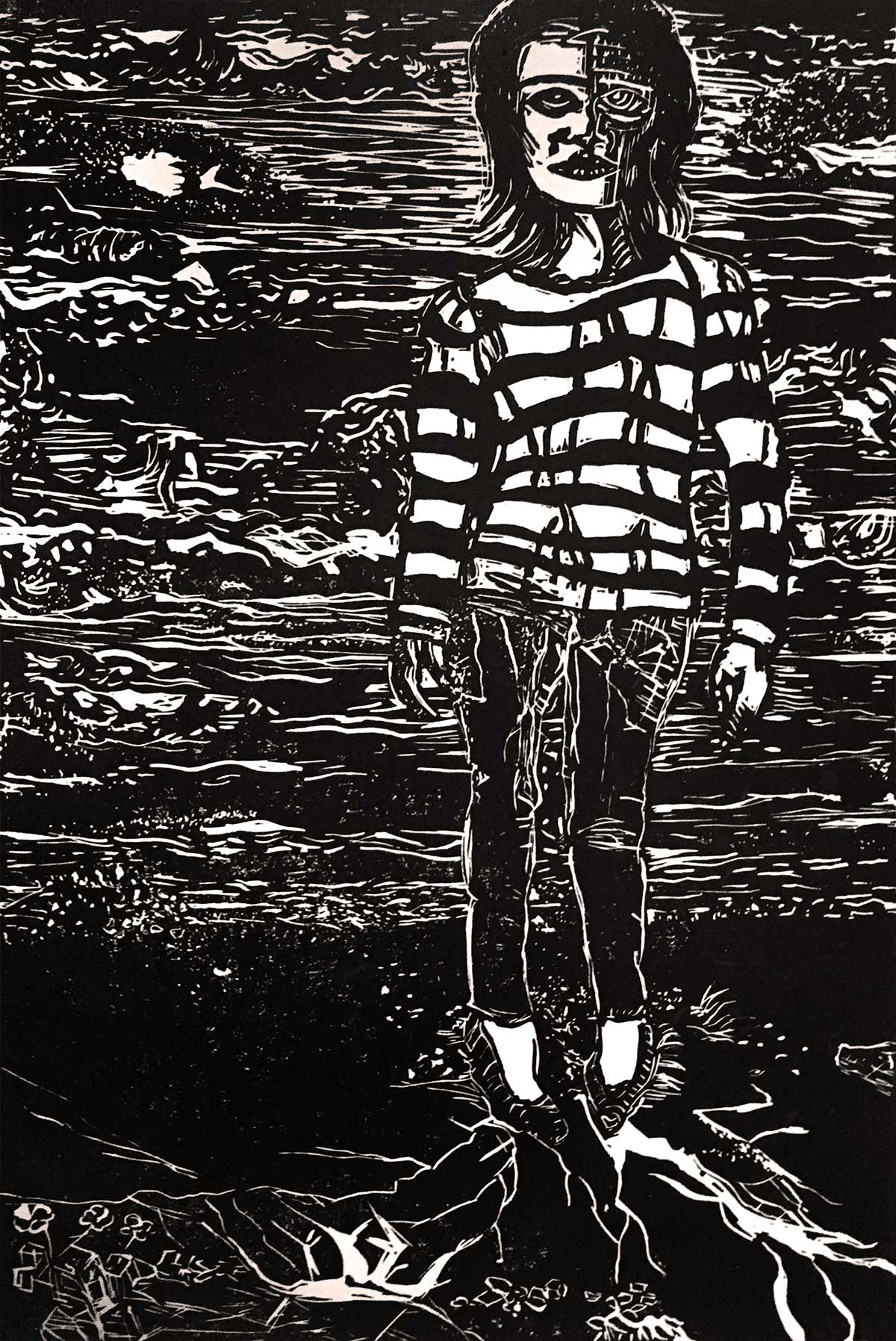

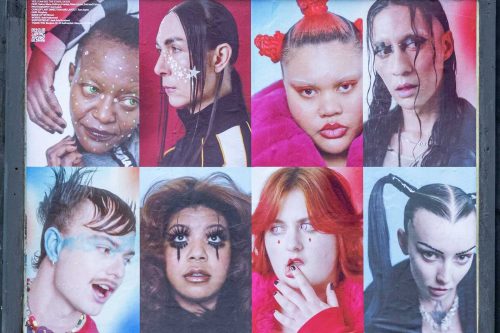

Derek Mawudoku’s imagery, according to renowned artist/educator Jon Thompson, “is always raw and uncompromising. Often heavy with psychological affect… fear… joy… pain… Sometimes it is childlike, giddy, funny, sometimes angry. Always it is intensely human.”

Born in London in 1959, Mawudoku graduated from Goldsmiths College in 1987 with a First Class BA (Hons) in Fine Art. His work has been included in a number of solo exhibitions over the years in addition to appearing in many group shows. Influences include outsider art, comic books, graphic novels plus artists such as Jean Debuffet, Otto Dix and Kathy Kollowitz.

Dynamic drawing and inventive compositions intensify his subject matter which is often an exploration of the physical and psychic tension between people in various environments. Subtle narratives are suggested by the interaction of Mawudoku’s compelling characters and the darkly poetic atmospheres he creates.

Images by Derek Mawudoku

Images by Derek Mawudoku