Partnerships

The three British Bangladeshi artists bringing “Bidrohi” to the historic rafters of Old Spitalfields Market

British Bangladeshi artists Ace Rahman, Mohammed Z Rahman, and Puer Deorum deliver “Bidrohi”, a moving collection of paintings, self-portraits, and photographs suspended in the lofty heights of Old Spitalfields Market. Occupying a space home to the East End rag trade, and also representing an enduring reminder of the legacy of South Asian migration, “Bidrohi” is a fluent and insightful ode to Bangladeshi identity and ancestry. The project was done in partnership with JACK ARTS and curated by Maria Guy.

There’s something more to Old Spitalfields Market than the scores of people browsing table tops and shops through daylight hours; there’s a resounding echo of the East London rag trade, and a history that weaves its way through South Asian migration and localised craft. Glance up to the rafters this autumn and you might catch a glimpse of “Bidrohi”, a resplendent collection of work from three remarkably talented British Bangladeshi and Bengali artists, namely; Ace Rahman, a multi-hyphenate walking the tightrope between digital and traditional practices, Mohammed Z Rahman, visual artist and writer exploring the socio-political through dreamscapes and the domestic, and Puer Deorum, interdisciplinary artist and curator navigating radical imagination, polychronic experiences, and non-linear realities through their practices of performance, photography, and set design (to name a few).

“Bidrohi” as a collection speaks to the legacy of migration, something that Mohammed has explored throughout his catalogue of work; “I feel like stasis is not the norm – there has always been movement of people,” he shares earnestly, “I think I’m trying to normalise, or validate this kind of creolised identity of Bangladeshis in Europe, and their wider histories and interactions with other diasporas”. This feeling of liminality and difference is critically articulated through each artist’s work, with a candid mix of street photography, self-portraits, and domestic scenes caught in paint each depicting a shared but unique interpretation of South Asian migration, by way of the East end.

When asked what “Bidrohi” means and the significance of this choice for the collection, Ace shares that the title references a poem by Kazi Nazrul Islam, a well-known Bangladeshi revolutionary poet that the three artists all felt connected to. “I personally feel that the poem and what it stands for is the essence of what it means to be a contemporary queer Bangladeshi artist in the modern age”, Ace shares, “it’s about standing up for your people and your land, and for what’s right”, something that each of the artists commit to unwaveringly.

Another organisation that has found their home in the East End by way of South Asia is Oitij-jo – “they’re a foundational hub that really supports this movement of British Bangladeshi artists”, Mohammed shares, a space which Ace also occupied during their first artists residency which, coincidentally, was facilitated and curated by Puer. Despite their distinct practices, the three artists appear to share a commonality beyond their respective canvases, speaking of each other’s work with fondness and interest, and demonstrating the importance of kinship in collaboration, as well as in ancestry.

21.11.24

Words by

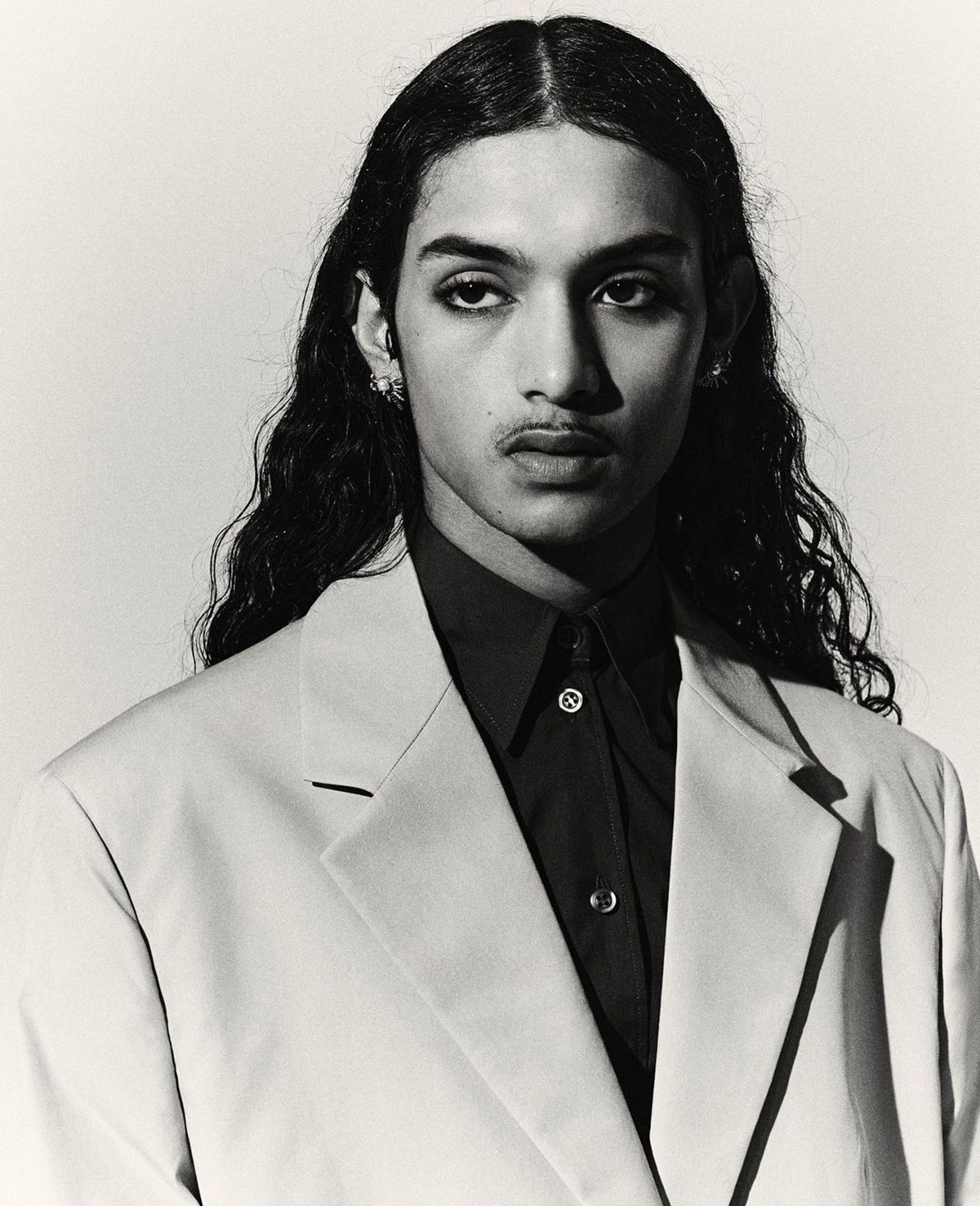

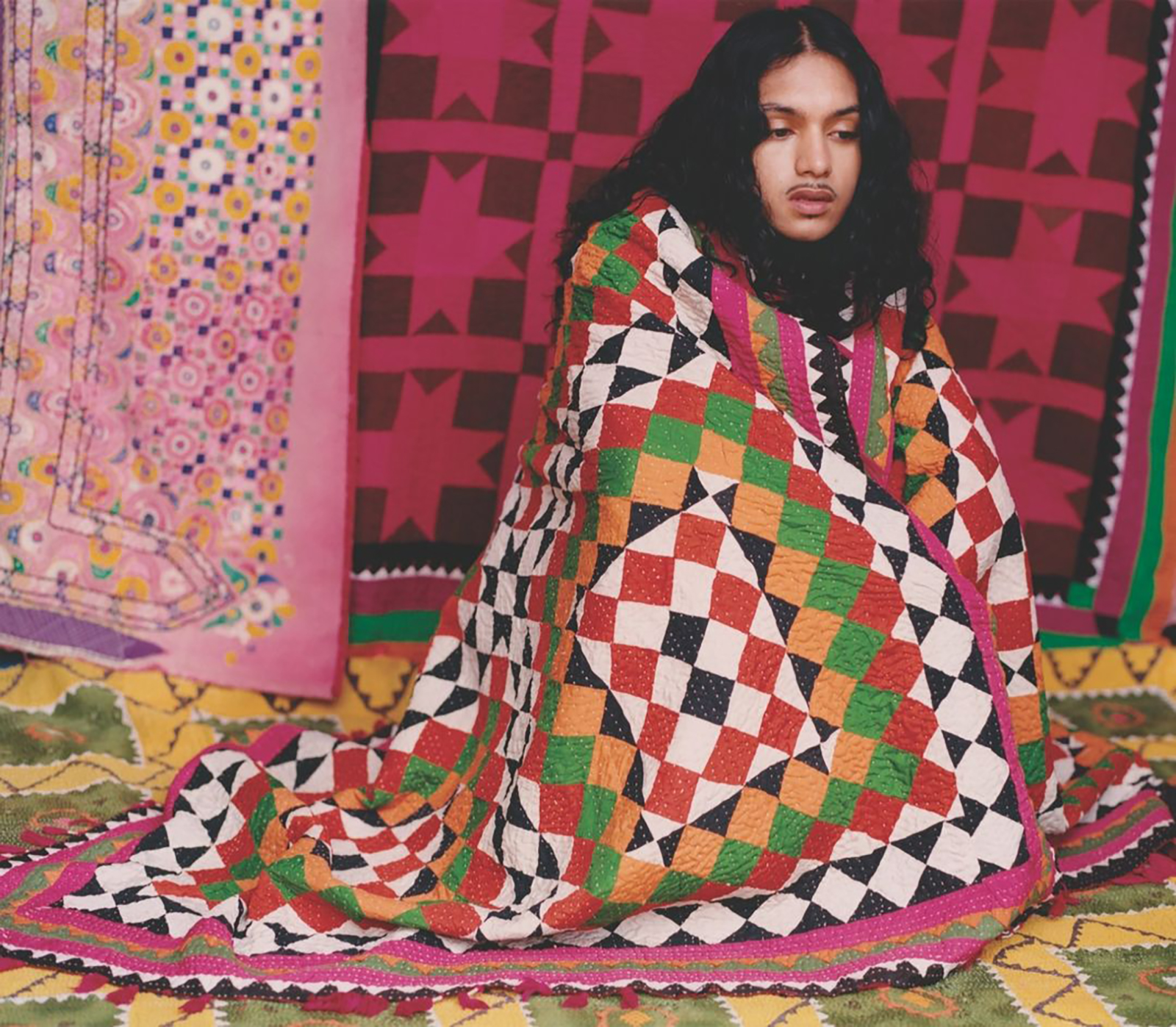

Ace Rahman

Ace Rahman

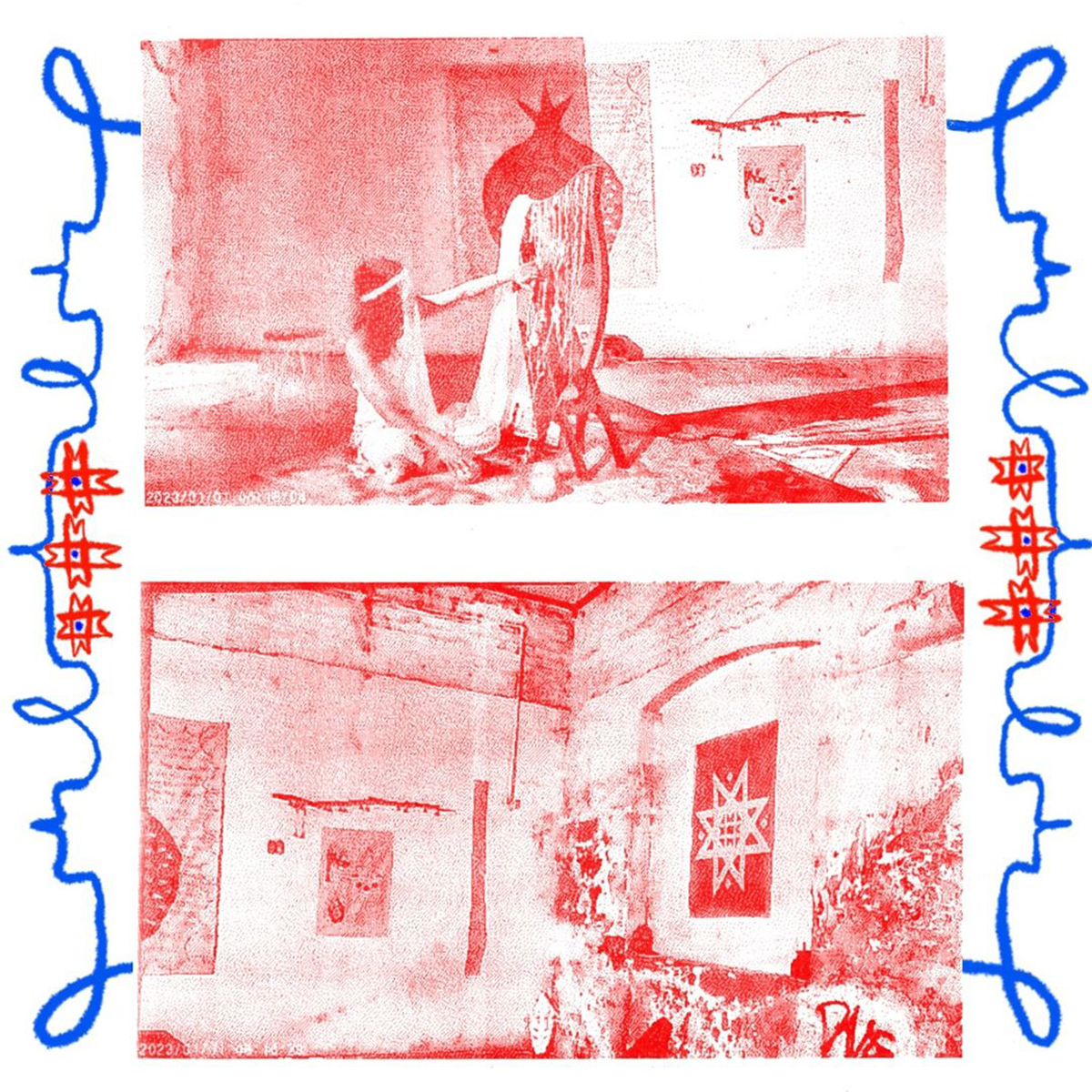

Stones of Baked Clay (2024), Live Performance, Dhaka, Bangladesh, Photo by Ruhul Abdin

Stones of Baked Clay (2024), Live Performance, Dhaka, Bangladesh, Photo by Ruhul Abdin

Mohammed / Photo by Gaia Bethel-Birch

Mohammed / Photo by Gaia Bethel-Birch

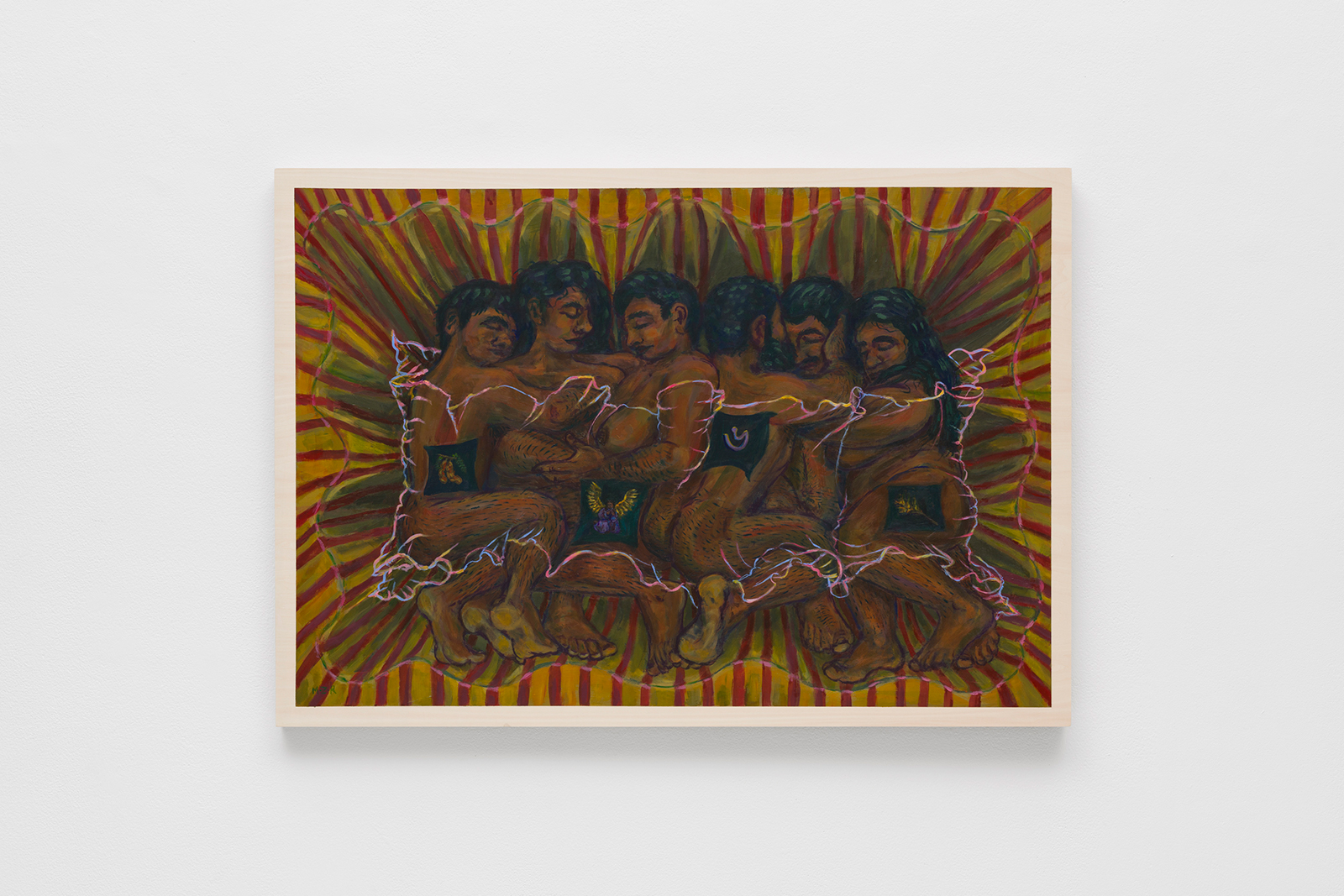

Barbecue (2024), 70cm x 50cm, acrylic on canvas, image courtesy of the artist and Phillida Reid, Andrew Judd

Barbecue (2024), 70cm x 50cm, acrylic on canvas, image courtesy of the artist and Phillida Reid, Andrew Judd

The Spaghetti House (2024), 173cm x 56 cm, acrylic on canvas, image courtesy of the artist and Phillida Reid, Andrew Judd

The Spaghetti House (2024), 173cm x 56 cm, acrylic on canvas, image courtesy of the artist and Phillida Reid, Andrew Judd

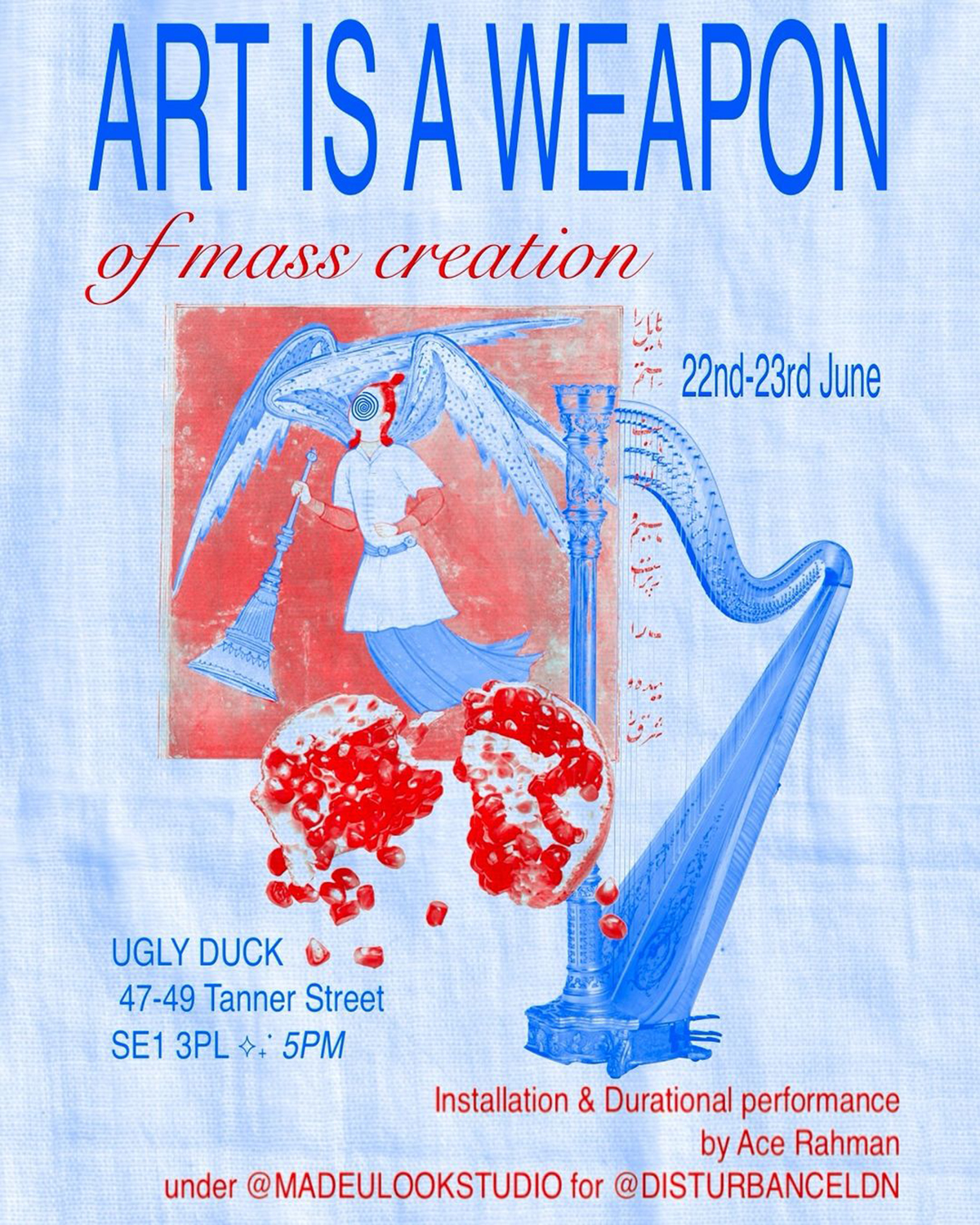

Cold Hands Get Stuck in Sand (2024), Live Performance, London, UK, Photo by India Bharadwaj

Cold Hands Get Stuck in Sand (2024), Live Performance, London, UK, Photo by India Bharadwaj

Portrait of A Pengali (2023), Mixed Media Sculpture, Photo by Laisul Hoque

Portrait of A Pengali (2023), Mixed Media Sculpture, Photo by Laisul Hoque

Costume for Dahong as O-Lan, Still from The Bang Straws (2021) by Michelle Williams Gamaker

Costume for Dahong as O-Lan, Still from The Bang Straws (2021) by Michelle Williams Gamaker

The Lovers (2024), 100cm x 70cm, acrylic on wooden board, image courtesy of the artist and The Approach

The Lovers (2024), 100cm x 70cm, acrylic on wooden board, image courtesy of the artist and The Approach

Pingala's Sequence (2021), Live Performance, London, UK, Photo by Yasmine Akim

Pingala's Sequence (2021), Live Performance, London, UK, Photo by Yasmine Akim

Costume for The Silver Maiden, Still from Thieves (2023) by Michelle Williams Gamaker

Costume for The Silver Maiden, Still from Thieves (2023) by Michelle Williams Gamaker