Partnerships

The Chemical Brothers are reflecting on their histories, cosmically

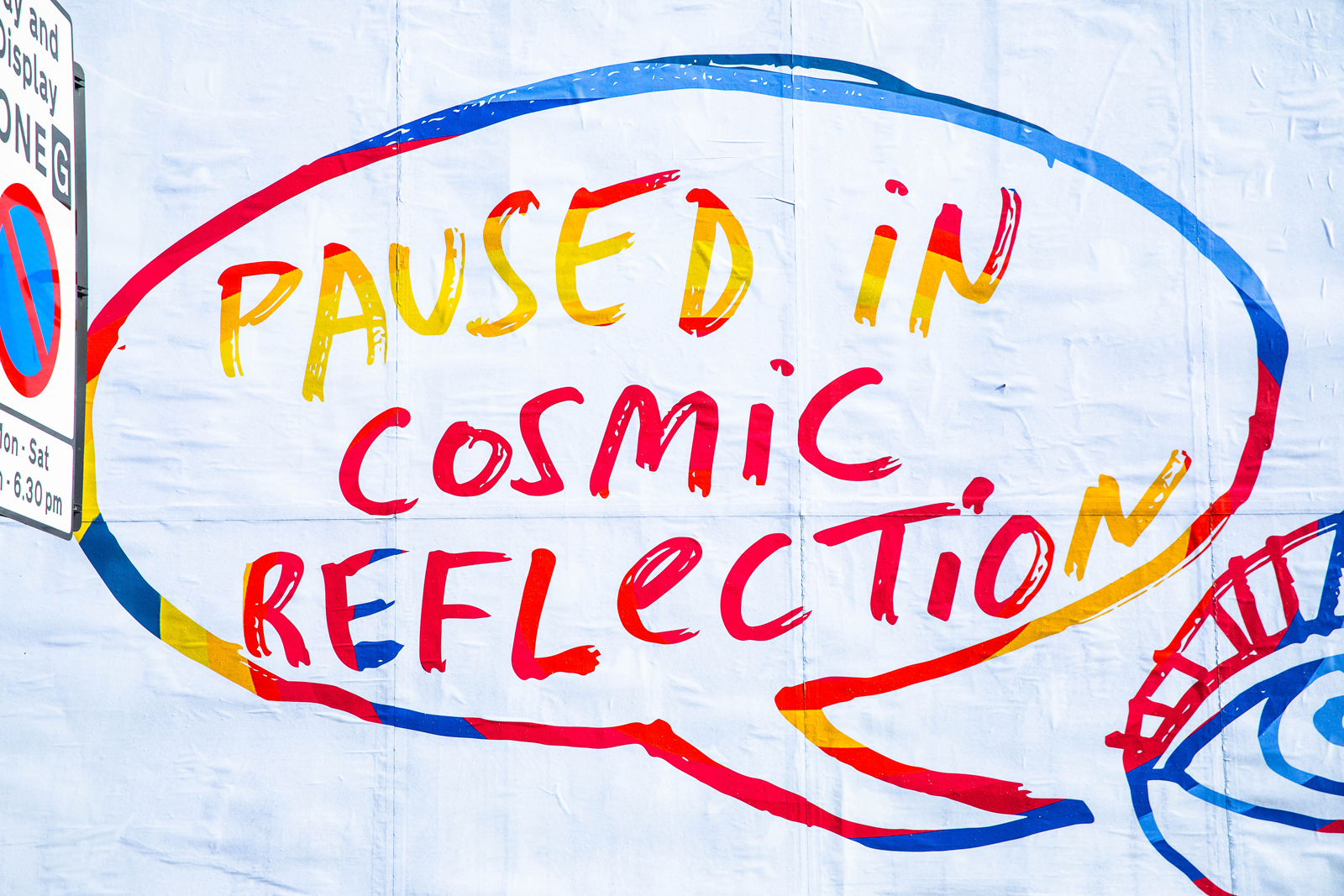

Long-time Chemical Brothers associate and author Robin Turner was on the bus in Bristol when he saw the posters for his book Paused in Cosmic Reflection. It tells the story of The Chems with over 300 pages of artwork, photography, video stills and interviews with Tom Rowlands, Ed Simons and their many creative collaborators.

“I texted a mate when I saw them and said – and this sounds ridiculous – it feels like being a pop star. Something you’ve done has been plastered all over the walls. I never thought I’d experience that,” says Turner, who has worked for the band as a writer and press officer on and off for the last 30 years. “I’m always one step removed. I see posters for bands I work with. I see a Chemical Brother’s poster and I feel proud because I’m part of it, but the book – it’s weird. It’s a very warm feeling.”

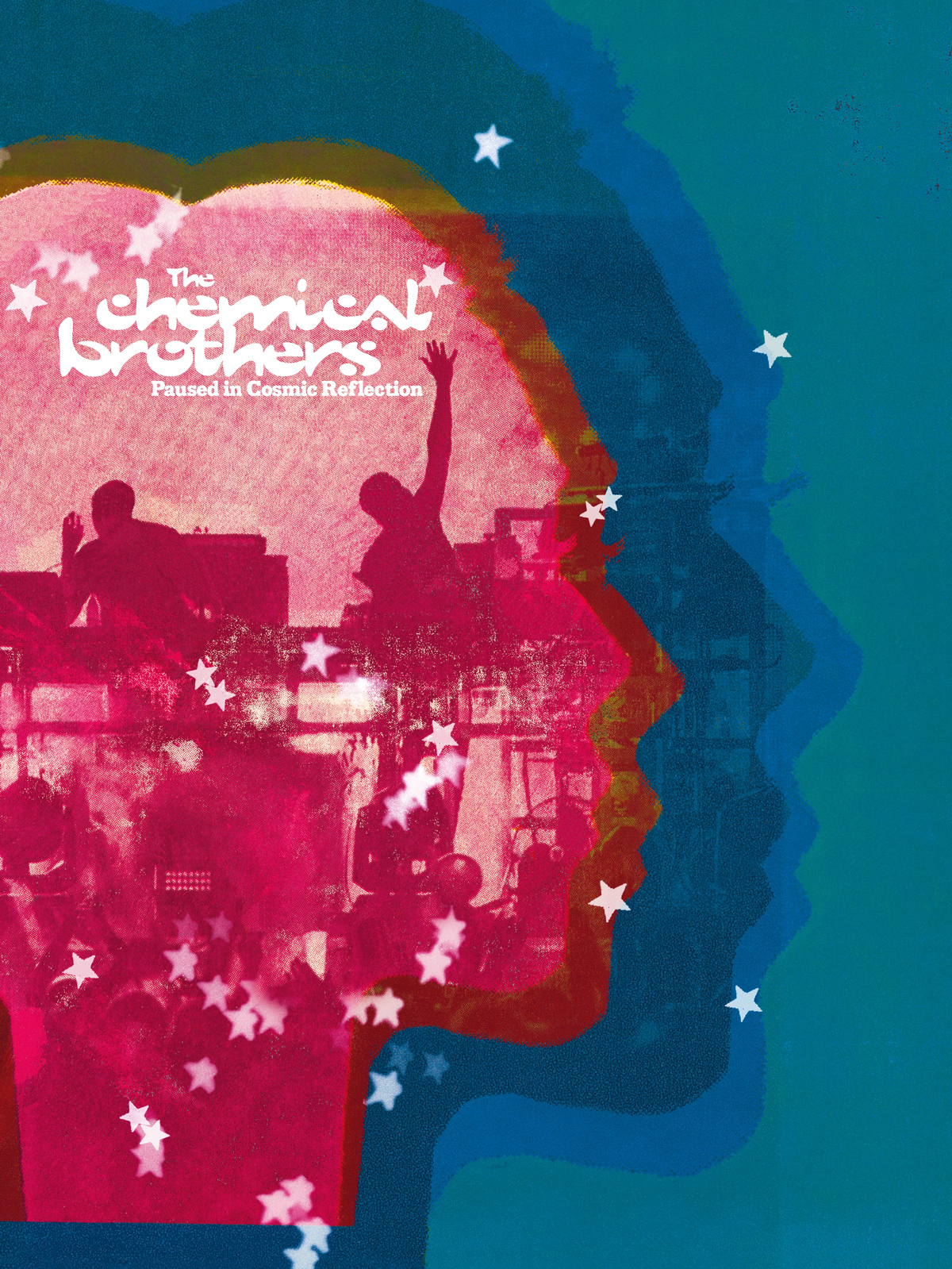

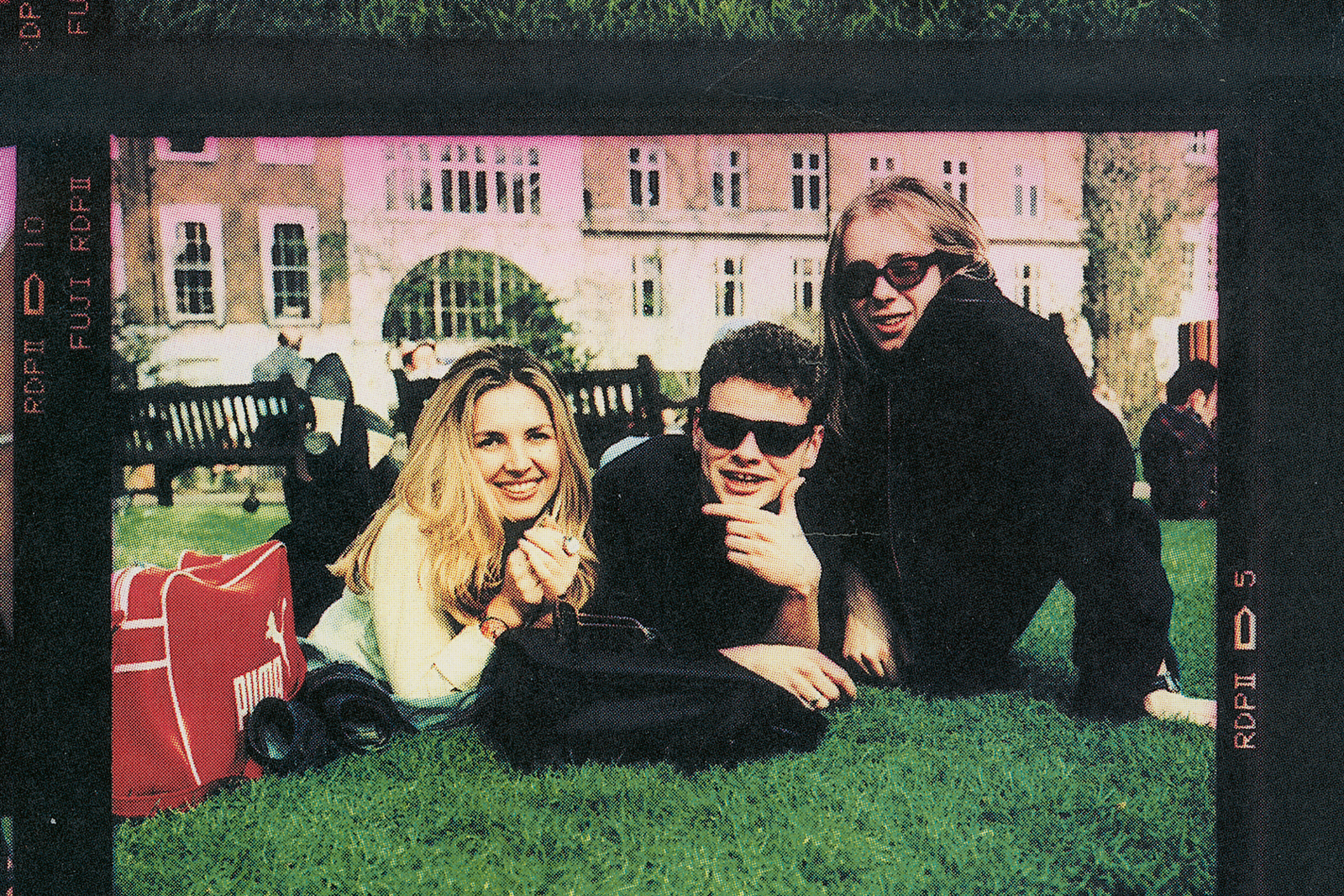

Paused in Cosmic Reflection positions the band as the centre of a hyper-visual world. Turner went into the Chemical Brothers’ archive in their south coast studio to select iconic images, flyers and posters, and there’s a bespoke cover designed by their long-term artist Kate Gibb. Design duties went to filmmaker and visual artist Paul Kelly (Finisterre and This Is Tomorrow). It had been out for less than a fortnight when Rough Trade Books named it #3 in their top books of the year after Jeremy Deller’s Art Is Magic and Thurston Moore’s Sonic Life memoir.

21.11.23

Words by

Joseph Cultace

Joseph Cultace

Mark McNulty

Mark McNulty

Mark McNulty

Mark McNulty

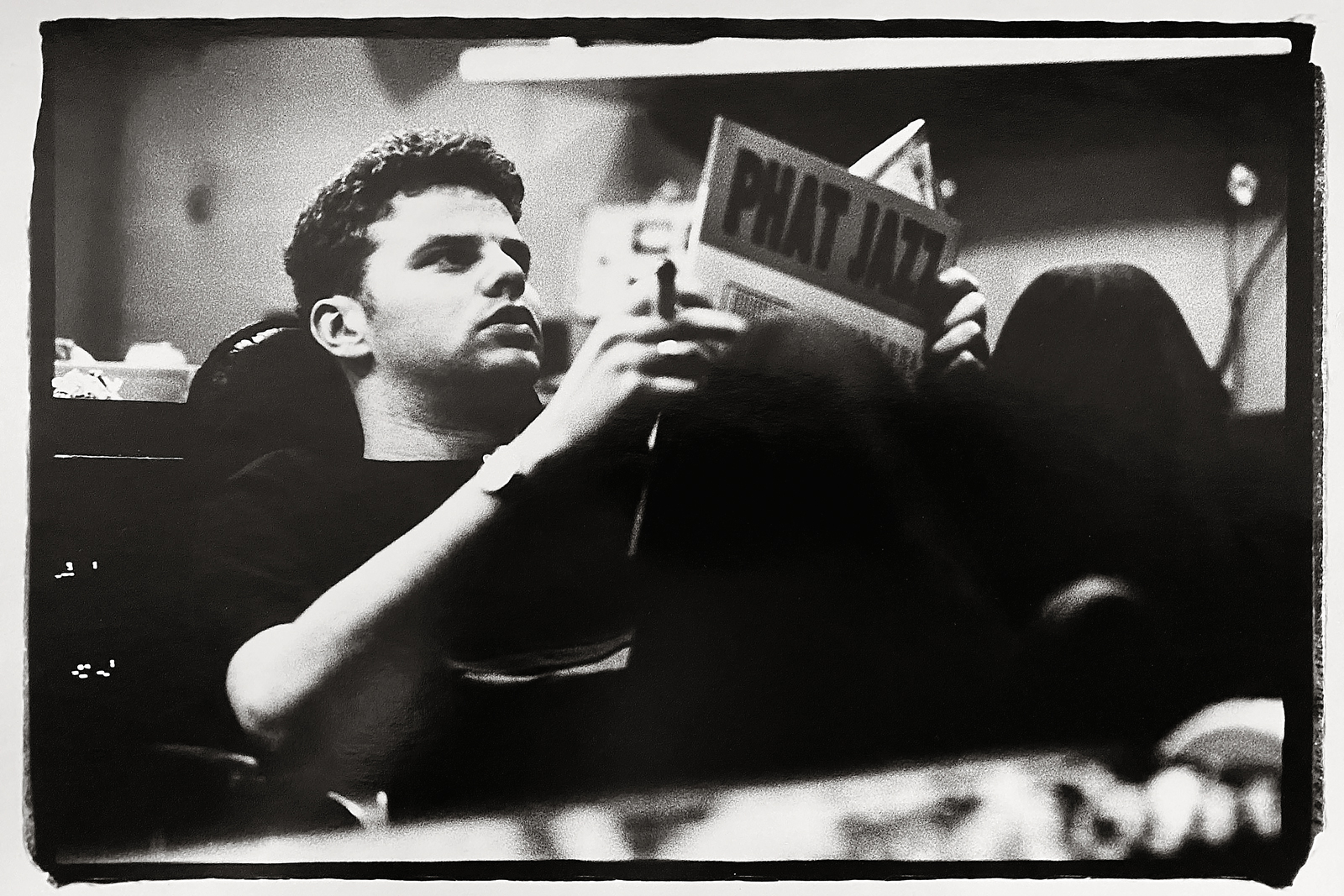

Phat Jazz

Phat Jazz

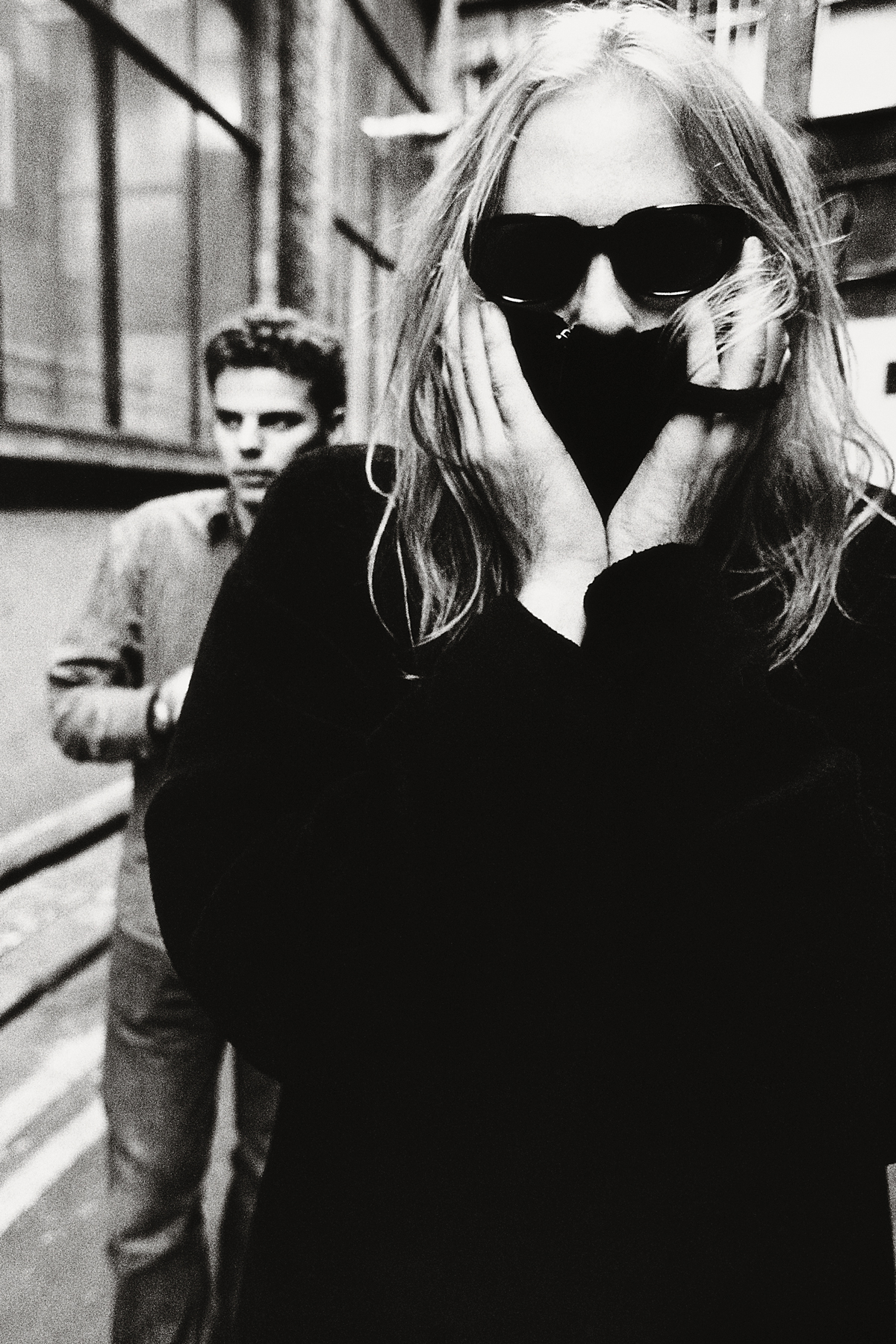

Hamish Brown

Hamish Brown

Jake Davis

Jake Davis

Laure Vasconi

Laure Vasconi

Hamish Brown

Hamish Brown

Sarah Cracknell (Saint Etienne)

Sarah Cracknell (Saint Etienne)