Your Space Or Mine

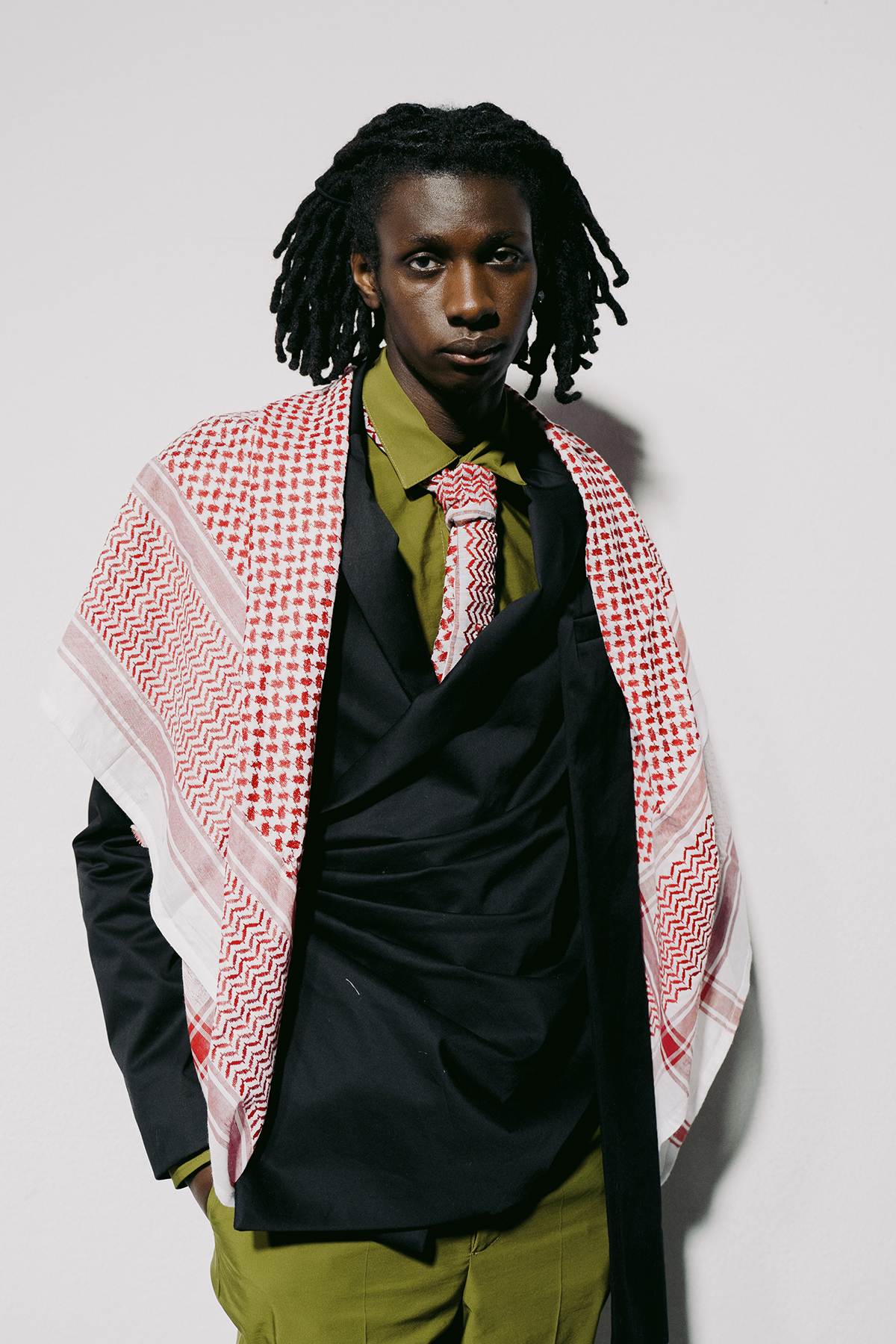

Sideways not upwards: Kazna Asker on Activism, Community and ‘wearing what I believe in’

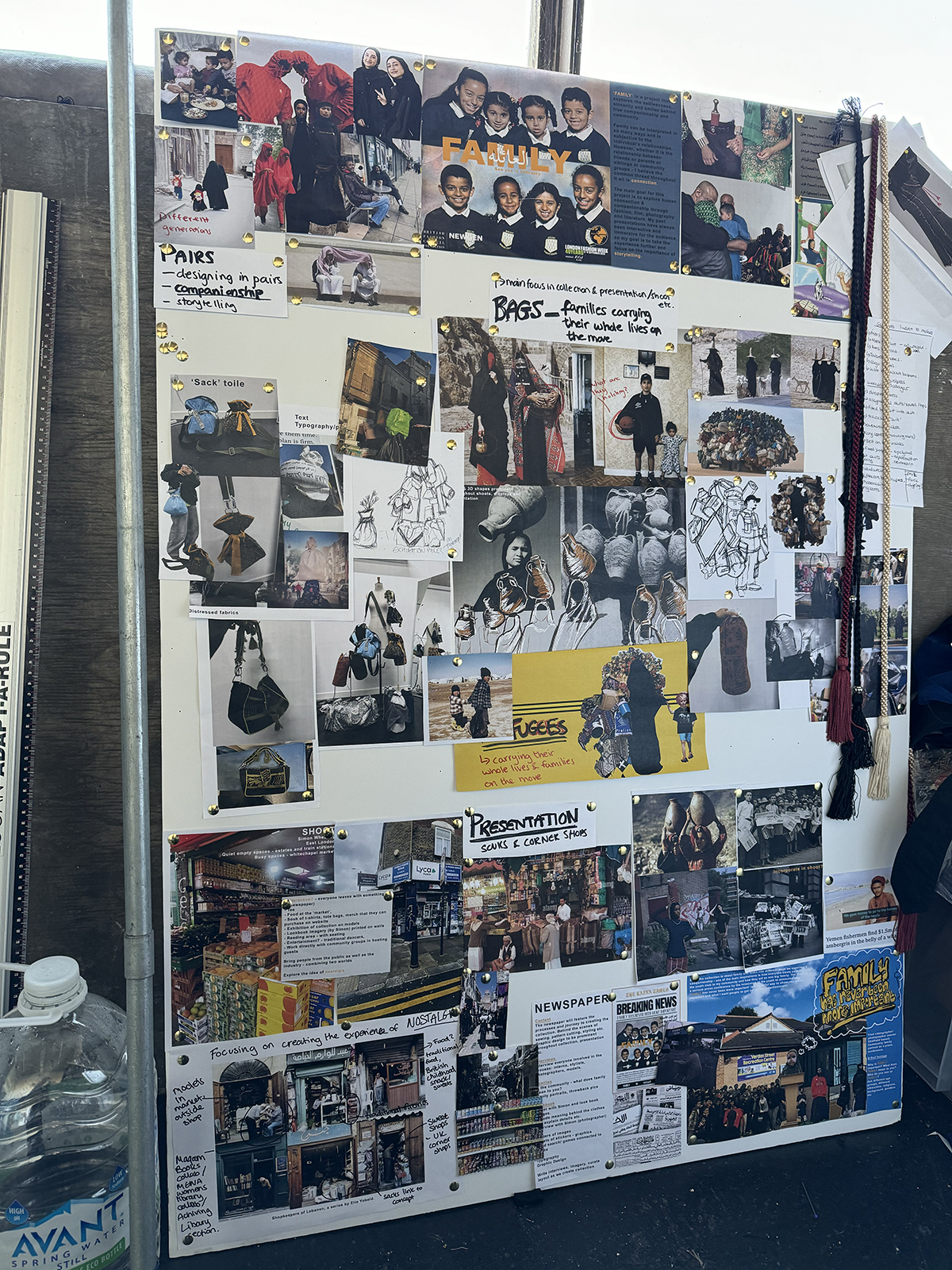

When asked about her proudest moment, Kazna Asker doesn’t talk about Fashion Week or industry prizes. She points to a film she made about Sheffield. It wasn’t glossy or designed for a fashion audience, but it was hers: a portrait of her city, its people, its streets, and the everyday lives that shaped her. For Kazna, that was the point — to show Sheffield as she knows it, and to hold up the voices and stories that don’t always get heard.

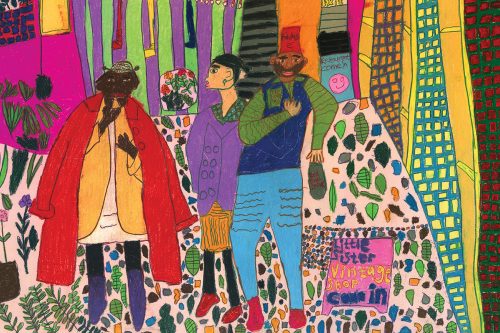

That instinct to document, to preserve, to show the value in the communities she knows best, is where her practice begins. It’s why she talks about “building sideways, not upwards.” It’s why she brings her friends and neighbours onto runways or reconstructs her grandmother’s living room at Fashion Week. Sheffield, and the community it represents, isn’t just her background, it’s her compass.

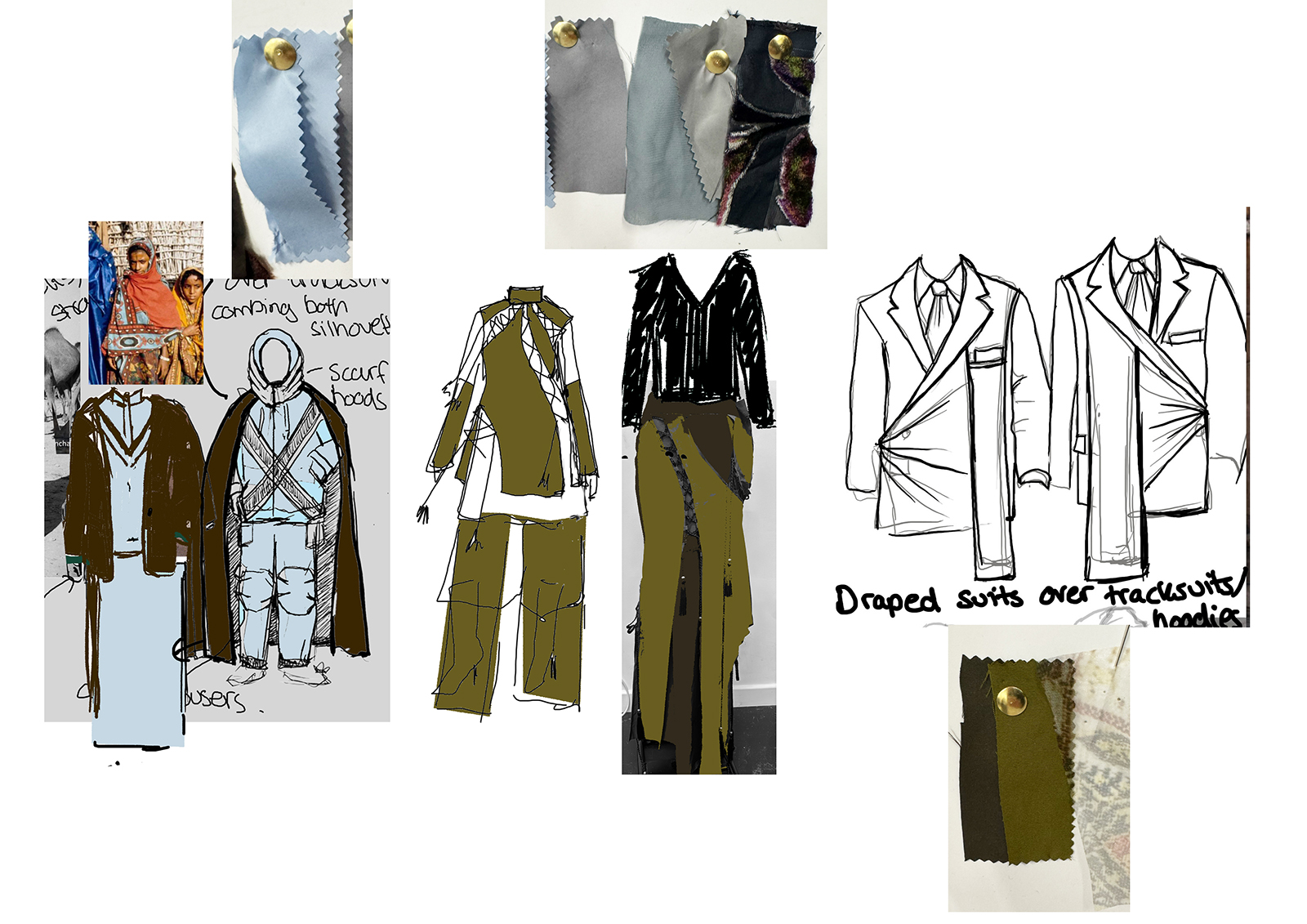

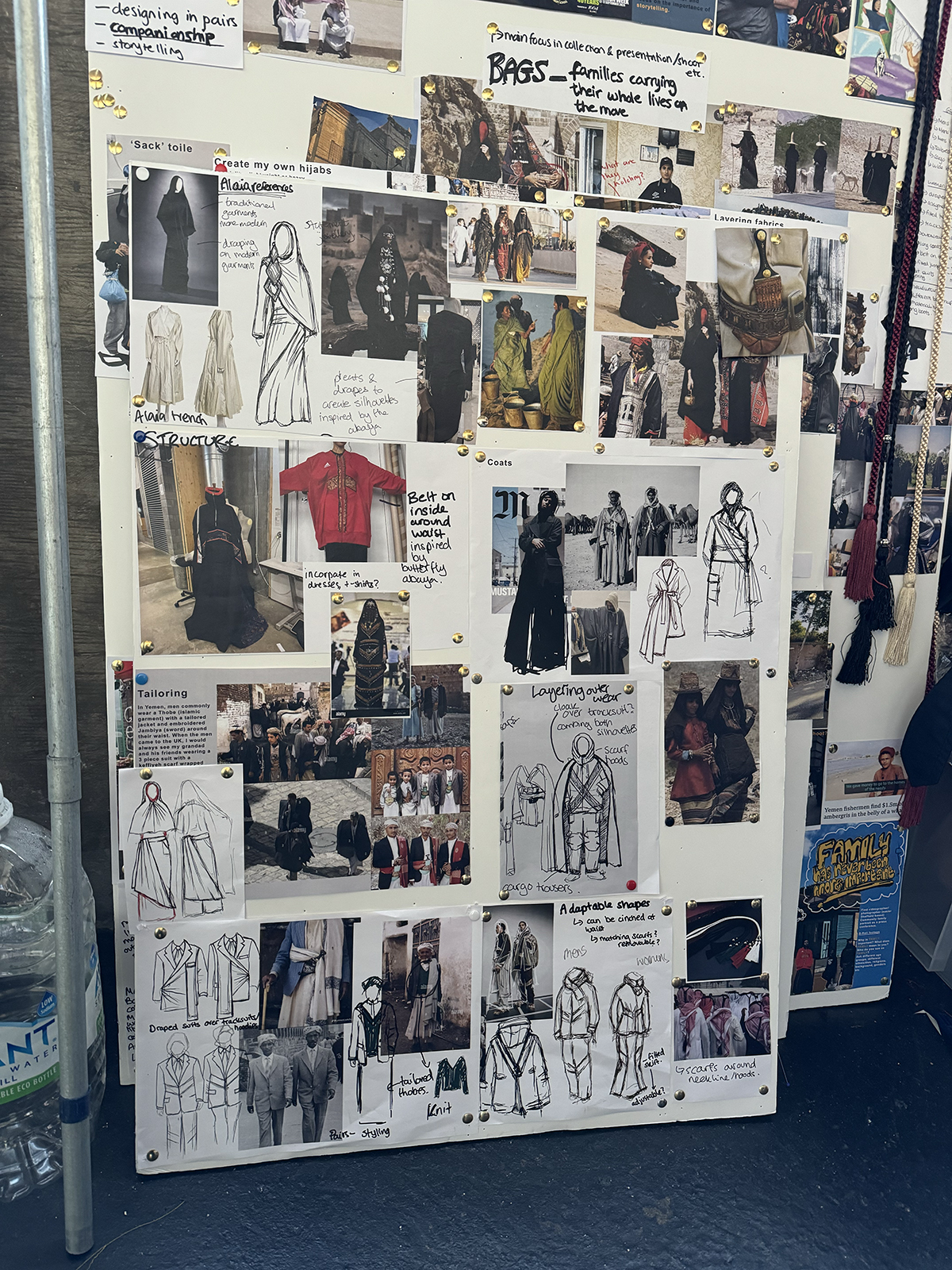

Her Yemeni heritage sharpened that perspective from the start. She grew up surrounded by its traditions, from the generosity and selflessness that ran through everyday life, to the visual richness of her family home. One room might be a traditional Yemeni space with patterned rugs, heavy curtains, and gold-framed mirrors. Next to it, the “British living room” as she jokingly calls it, with sofas facing the TV. At family gatherings, her aunties in abayas and hijabs would sit alongside cousins in Nike tracksuits. Breakfast might mean a full English, but always with Yemeni chai tea.

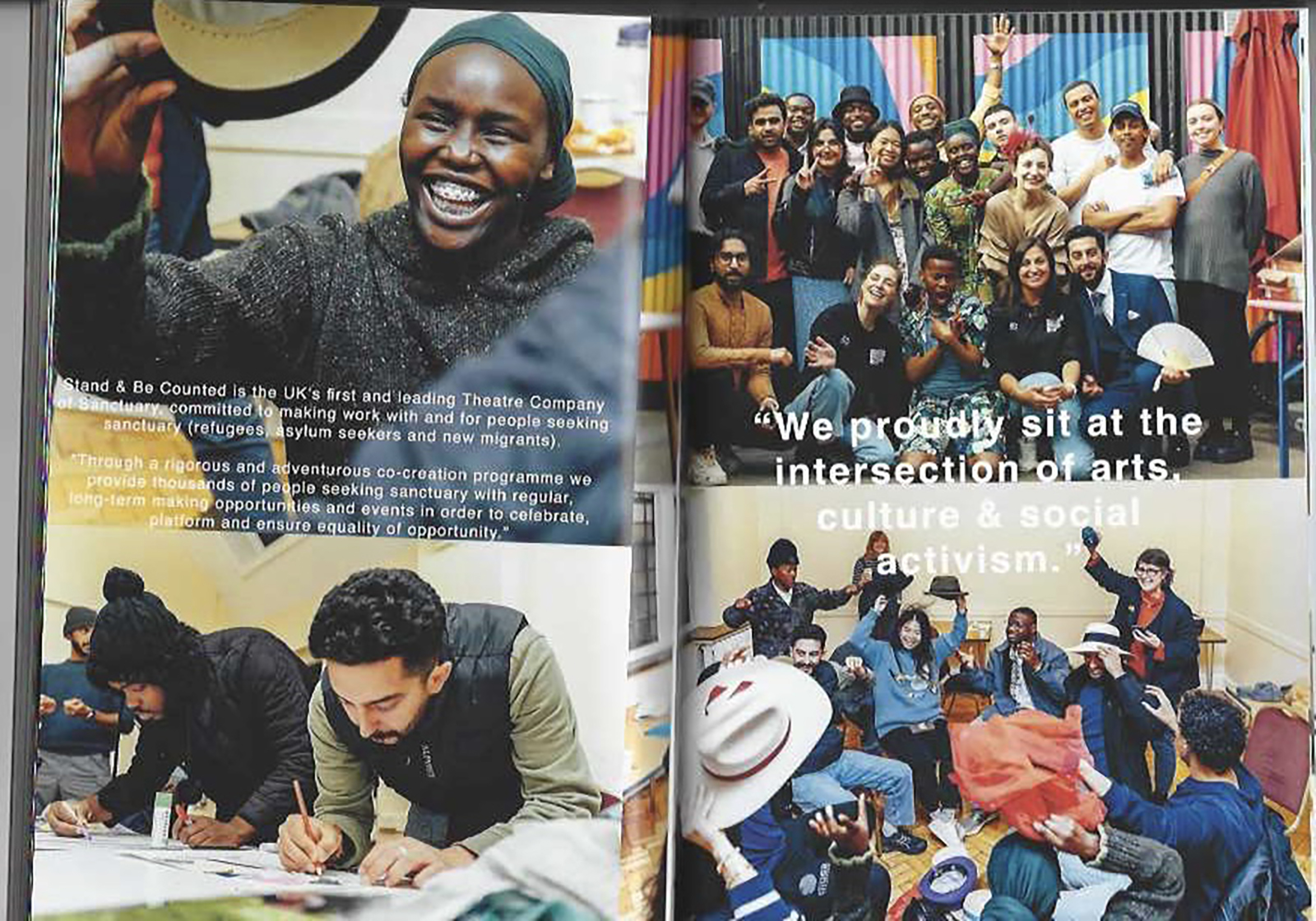

At the same time, youth clubs gave her values somewhere to grow. Spaces similar to Reach Up, where Kazna now volunteers, founded by Safiya Saeed (now Lord Mayor of Sheffield), became second homes for her and her siblings. Her parents were young when they had them, and youth clubs offered another safe, collective environment. Kazna says they instilled the importance of community from the beginning, lessons that have stayed with her even as most of those spaces have since disappeared from Sheffield.

11.09.25

Words by