Your Space Or Mine

Sgàire Wood takes her beguiling brand of image-making to the streets of Glasgow and Edinburgh

A glittering presence in Glasgow’s overlapping club, art and fashion scenes, Irish artist and performer Sgàire Wood is well-known for her maximalist, humorous work combining dance and spoken word with OTT make-up and costume design. With its twisted roots in drag, fashion photography and multi-artform nightlife scenes, Sgàire’s practice is concerned with image-making, pop-cultural symbolism and the dichotomy of authenticity and artifice – all themes she explores in her latest work for BUILDHOLLYWOOD’s ongoing Your Space Or Mine series, on show 18th November until 2nd of December throughout Glasgow and Edinburgh.

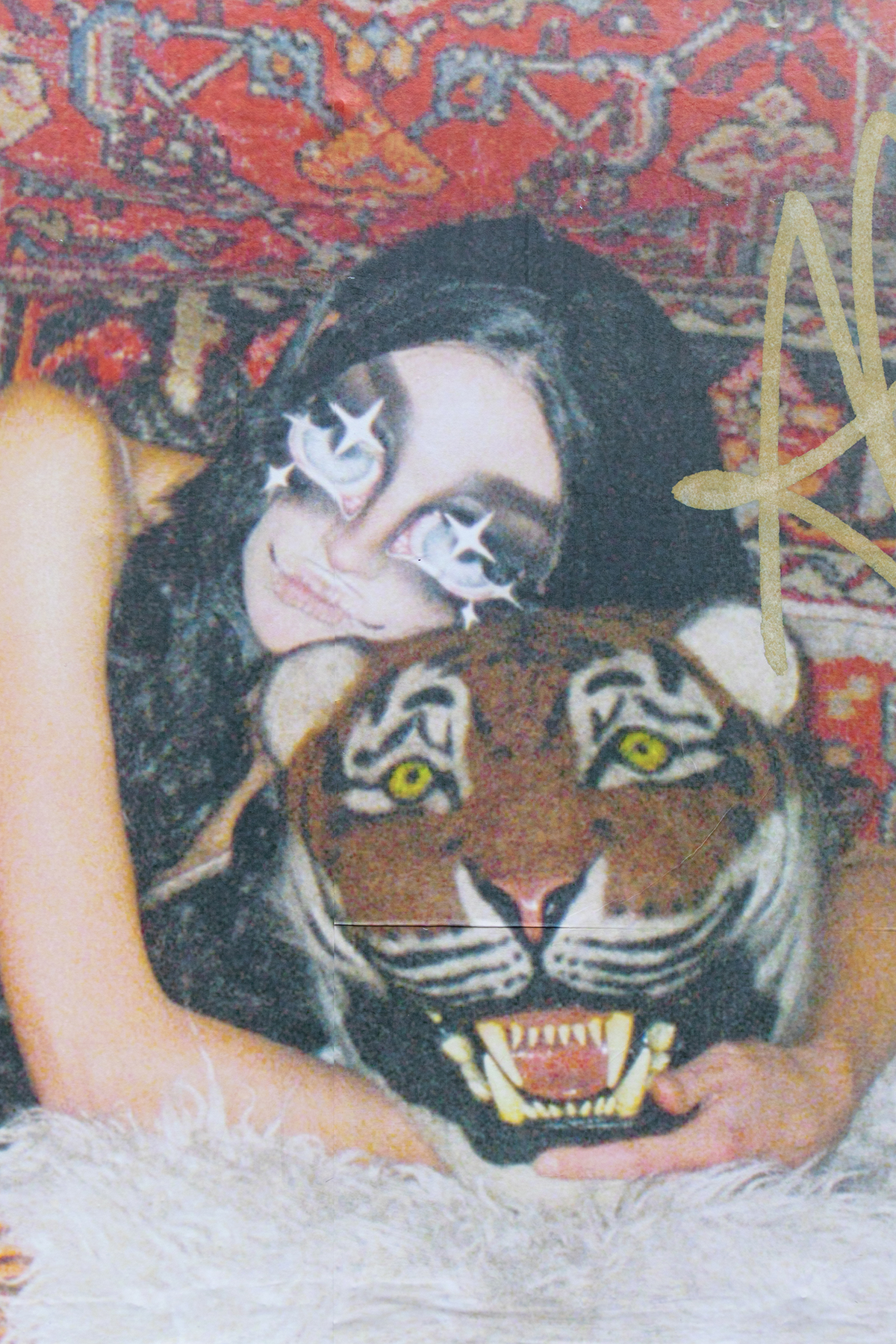

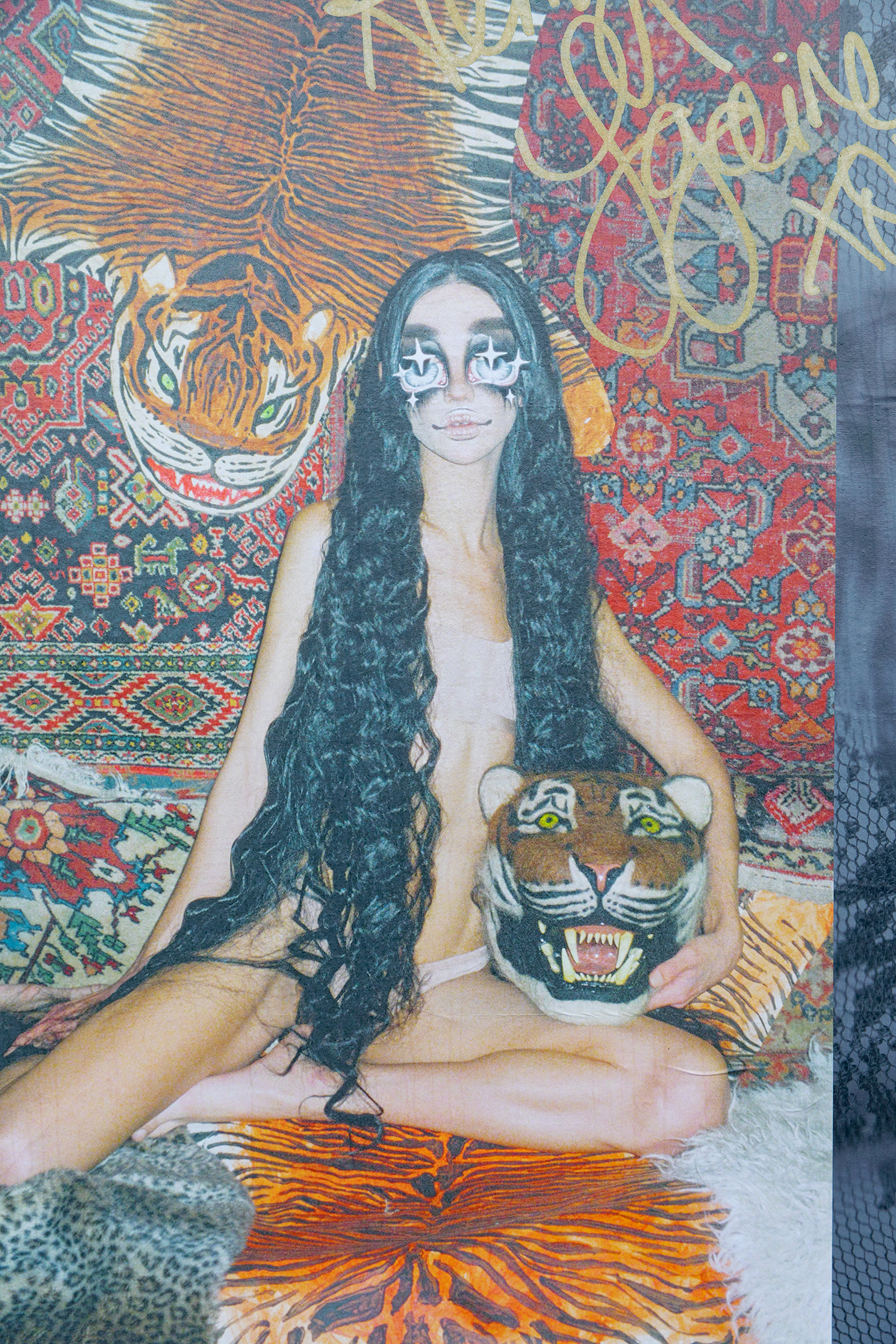

The most striking and recognisable element of Sgàire’s work is her signature doll-eye make-up: a hyperreal, hyper-feminine anime-esque look that speaks to the origin of glamour as a form of magical trickery. Equally alluring and disquieting, Sgàire transforms the make-up routine from a process of enhancement to an optical illusion in an accentuated take on the (specifically trans and queer) creation of identity. In 2020, she revealed the secrets behind her look via a make-up tutorial video for Vogue. In many ways the video could be considered her ultimate artwork, and the epitome of camp magnificence; a perfectly balanced critique/celebration of image-making on arguably its most storied platform.

Sgàire’s work is often situated in nightlife spaces, and there’s something of the ‘80s club kid in the way she melds avant-garde and pop references in these environments – much like her friends and frequent collaborators PONYBOY. She’s performed at clubs, Pride events and gallery parties throughout Europe, and she co-founded the much-missed Glasgow queer club Bonjour, where she hosted the legendary karaoke night Sgàiraoke. She has continued to develop this karaoke/performance art hybrid in venues around Scotland, including at Edinburgh Art Festival and Jupiter Artland’s annual queer party JUPITER RISING – this year she hosted dressed in an XXXXXL heavy metal longsleeve t-shirt, the arms dragging behind her like a bizarre bridal veil.

27.11.24

Words by

Image: Sgàire Wood, Jupiter Rising 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Edinburgh Art Festival. Photo: Tiu Makkonen.

Image: Sgàire Wood, Jupiter Rising 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Edinburgh Art Festival. Photo: Tiu Makkonen.