Partnerships

Memorial Dance stands tall in Bristol: To move is to remember

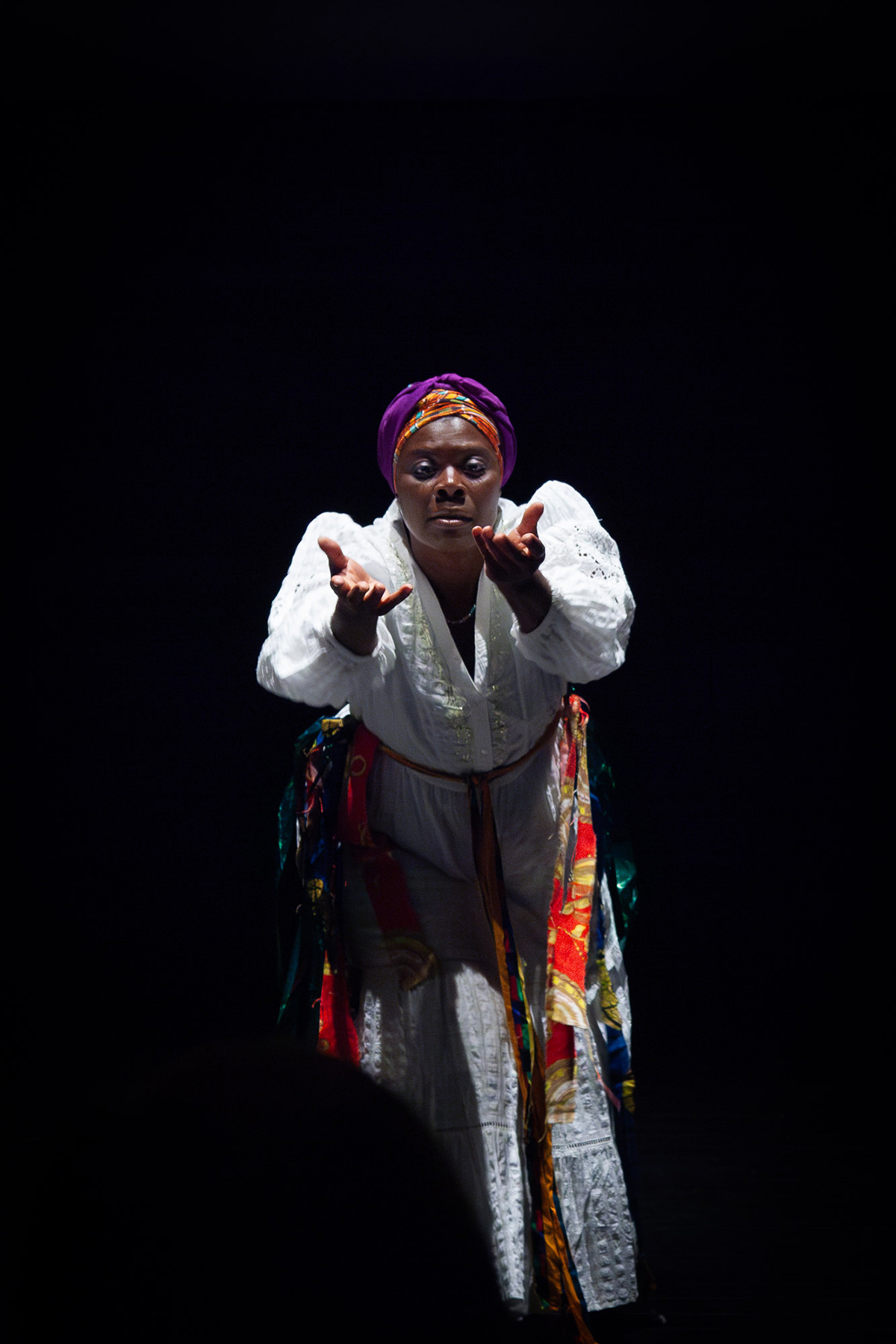

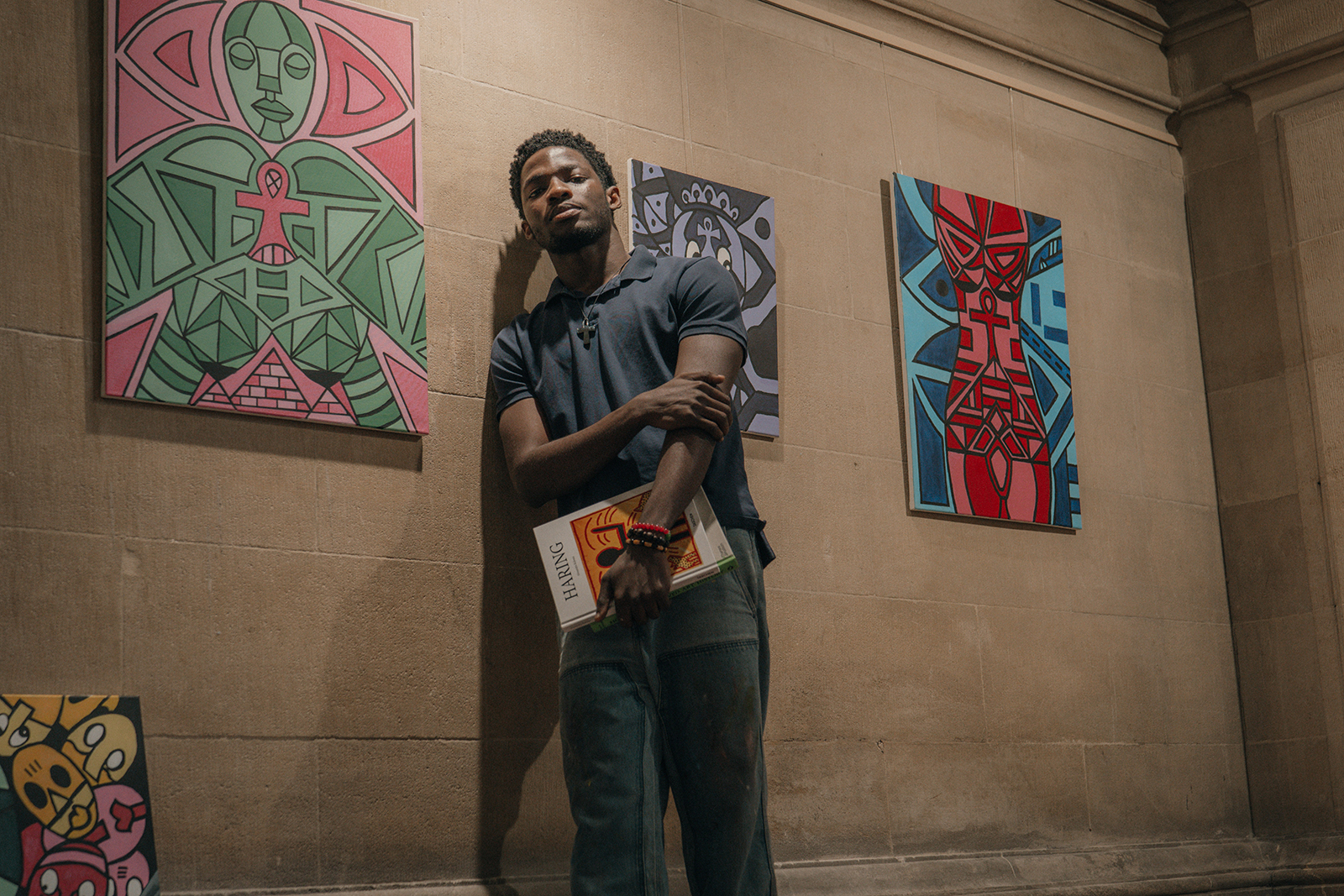

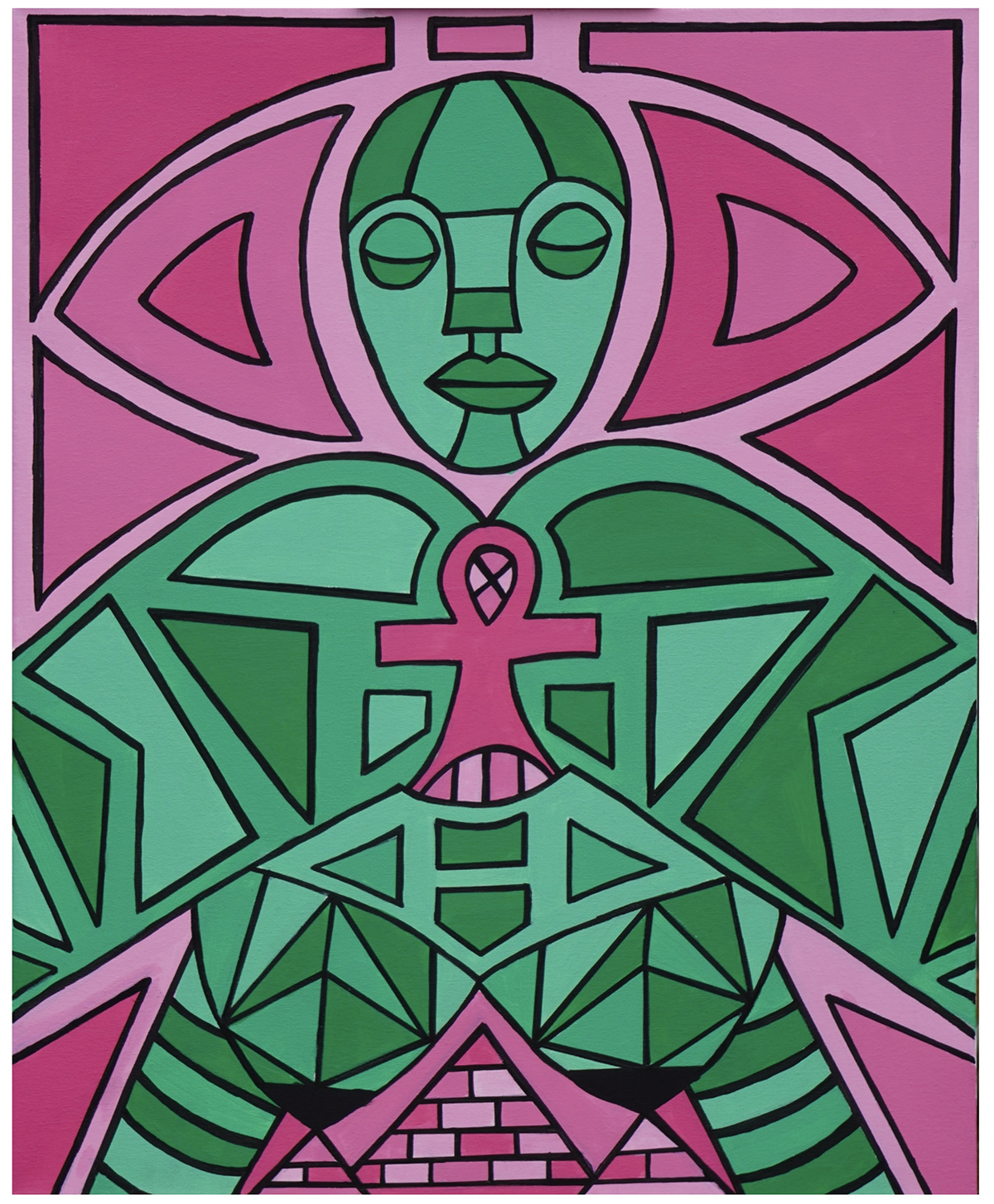

Pan-African in scope and Bristolian in grain, Memorial Dance is a living and breathing project created by artist, producer and researcher Cleo Lake, with an expansive billboard series created in collaboration with visual artist BÓLÁRÌNWÁ and BUILDHOLLYWOOD. Blending dance, storytelling and public art, it transforms remembrance into movement; a new kind of memorial rooted in collective repair.

Bristol has long been a city of movement; of ships, trade and migration, but also of protest and resistance. Memorial Dance, created by artist and former Bristol Lord Mayor Cleo Lake with Nigerian-born visual artist BÓLÁRÌNWÁ, channels that motion into an act of remembering. Drawing together artists and dancers, elders and young people through the Decolonising Memory Project, it transforms the body into an archive and the street into a site of reflection, where history and healing meet through movement.

Memorial Dance was built through community workshops that welcomed dancers and non-dancers alike, while holding an African-descent backbone at its core. Two anchor masterclasses seeded the choreography with specific diasporic lineages: Bristol teacher Norman “Rubba” Stephenson, whose practice carries threads from 1970s workshops by Steel ’n’ Skin through to the city’s own ensemble Ekome, and Latisha Cesar, whose Haitian spiritual forms locate the dance within a wider Atlantic continuum.

Bristol’s cultural infrastructure is part of the story too. The former Inkworks, now the Kuumba Centre, and organisations like Artspace Lifespace map a long arc of independent spaces where Black creativity has organised, gathered and thrived; it was at an Artspace Lifespace show that Cleo first encountered BÓLÁRÌNWÁ’s work and invited him to collaborate. The project’s original spark also came from a very Bristol kind of pragmatism: at the Regenerations conference, choreographer Kwesi Johnson urged Cleo not to wait for permission to reframe the city’s monuments; use an AR app, write your own plaque, expose another truth. That insurgent energy runs valiantly throughout Memorial Dance to this day.

06.11.25

Words by