Your Space Or Mine

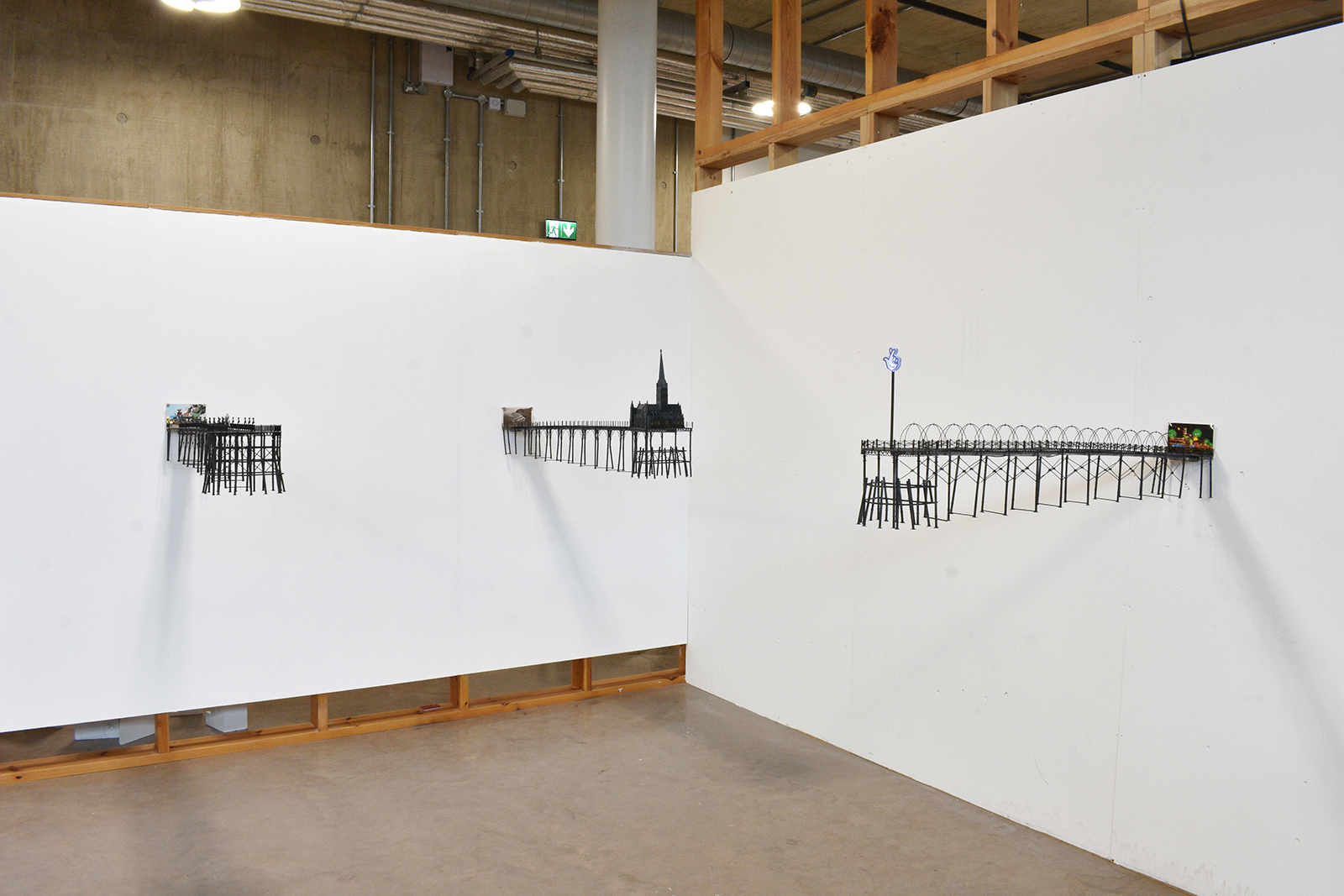

Max King turns social history into sculptural marvels

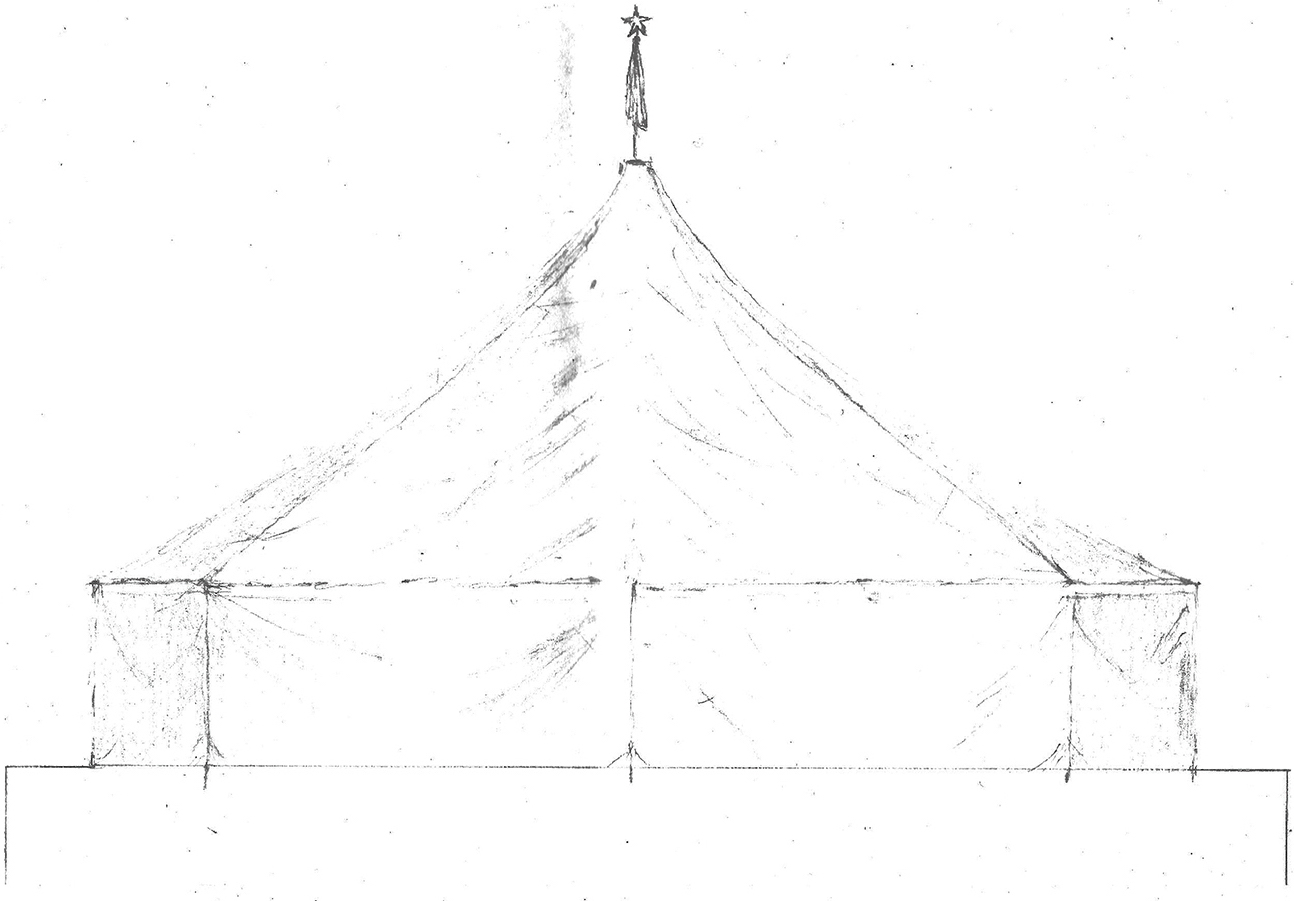

The artist is taking over BUILDHOLLYWOOD’s pocket sculpture garden in south London with an intricate installation that reaches back into Camberwell’s past

Max King has a knack for showing familiar objects and structures in a new light, and often in completely different proportions. Working in sculpture and installations, he toys with scale and perspective to create new encounters for his audiences, whether by collapsing buildings and other architectural structures into miniature models, or by blowing up small, everyday items such as pin badges into large-scale pieces that people can walk around. To him, presenting typical places and objects in atypical ways can be both magical and thought-provoking at the same time.

Born in Norfolk, now based in London, King studied graphic communication design at Central Saint Martins before doing an MA in Sculpture at the Royal College of Art. Different as they may seem, both courses left a profound imprint on his practice. His design education has no doubt been useful when it comes to the planning and construction of his sculptures. More importantly, it has meant that he keeps the functionality and experience of his pieces front of mind, always considering how people will interact with them. “I think a lot about the audience and how the audience will explore the objects, and I think that comes from my design background and always thinking about the user experience,” he says. “I know lots of people, especially artists, who don’t do that. But I always think about how someone seeing the work is going to move around it and how they are going to experience it, which is key.”

29.10.25

Words by

Photo credit: Max King

Photo credit: Max King