Partnerships

Love couldn’t tear them apart

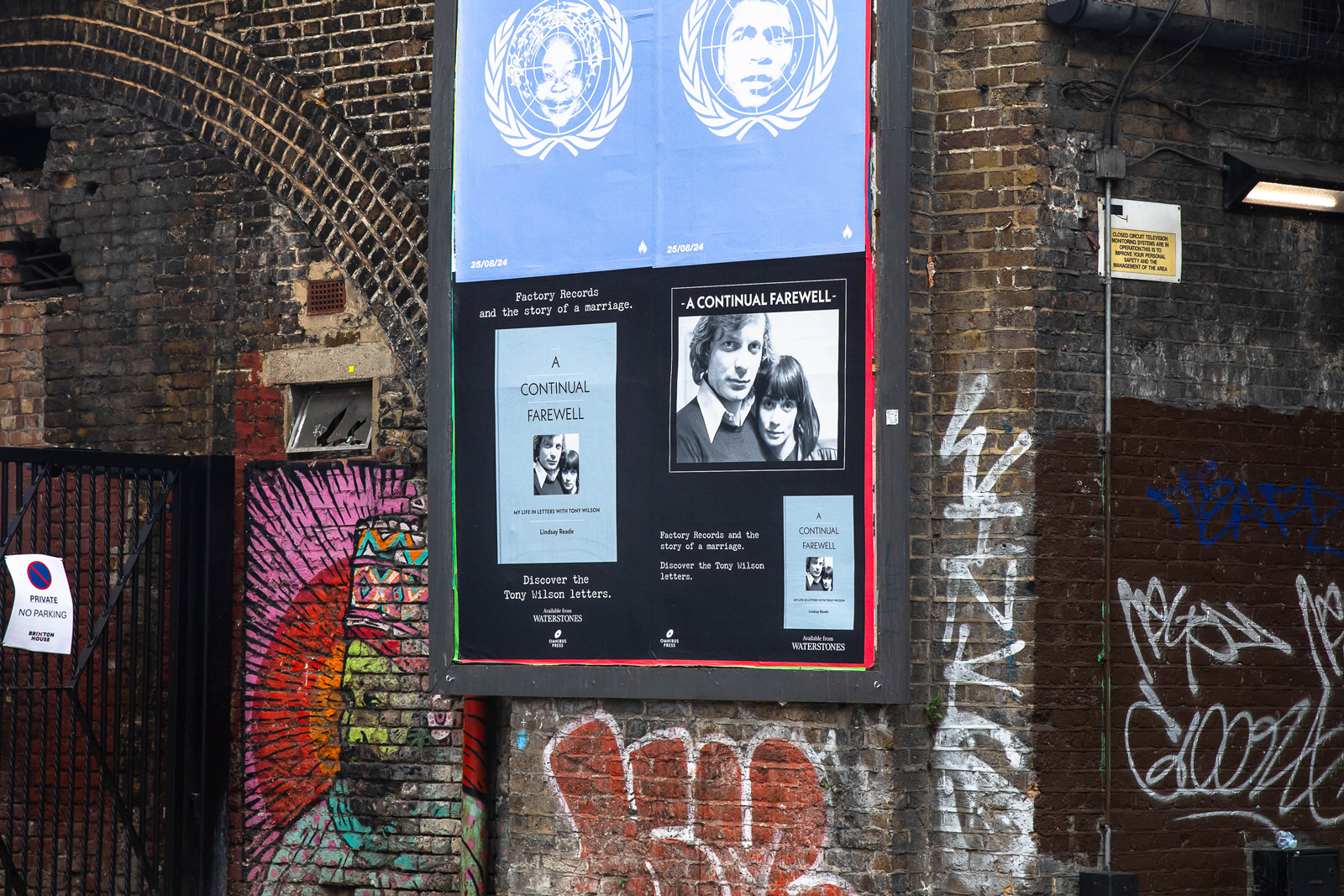

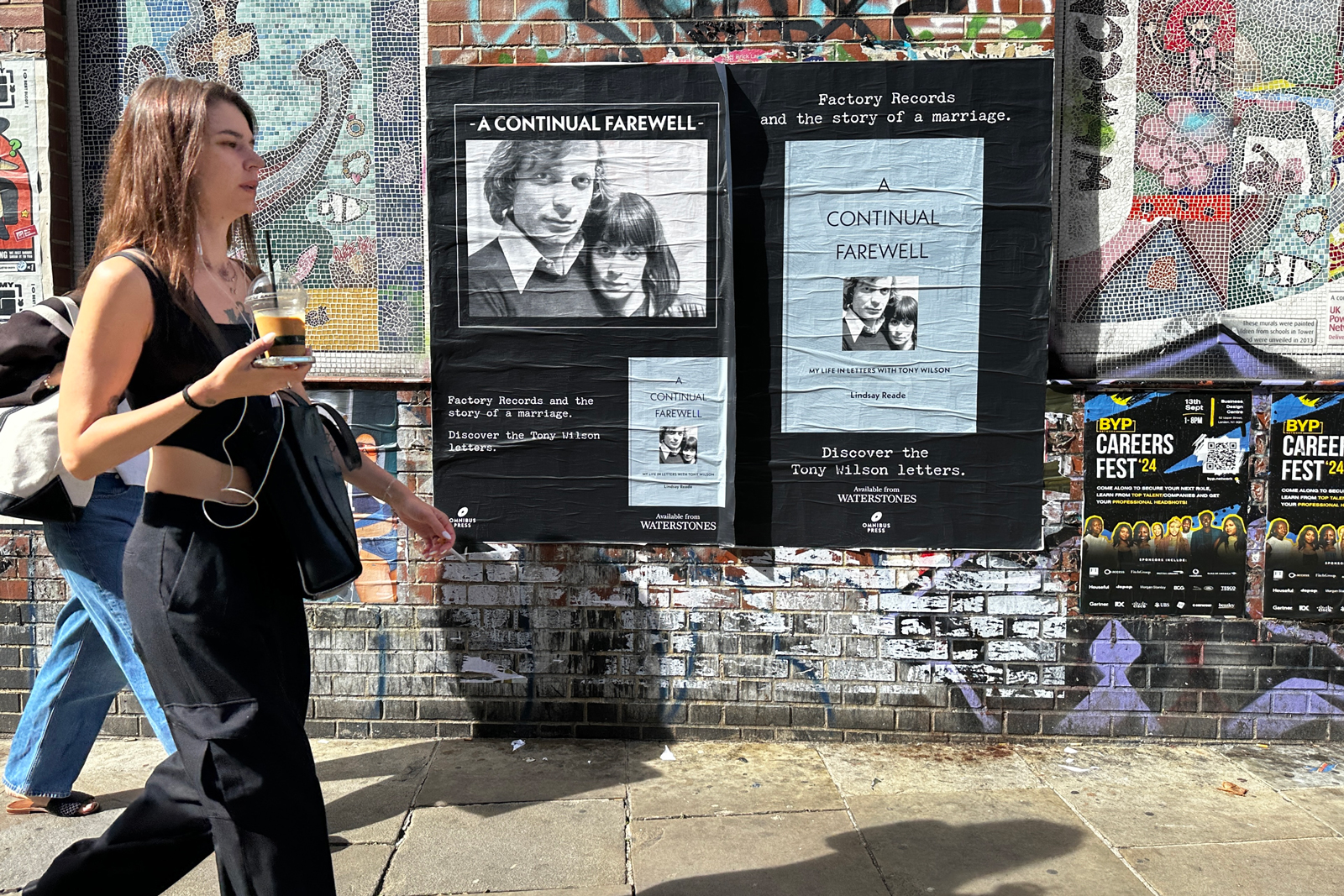

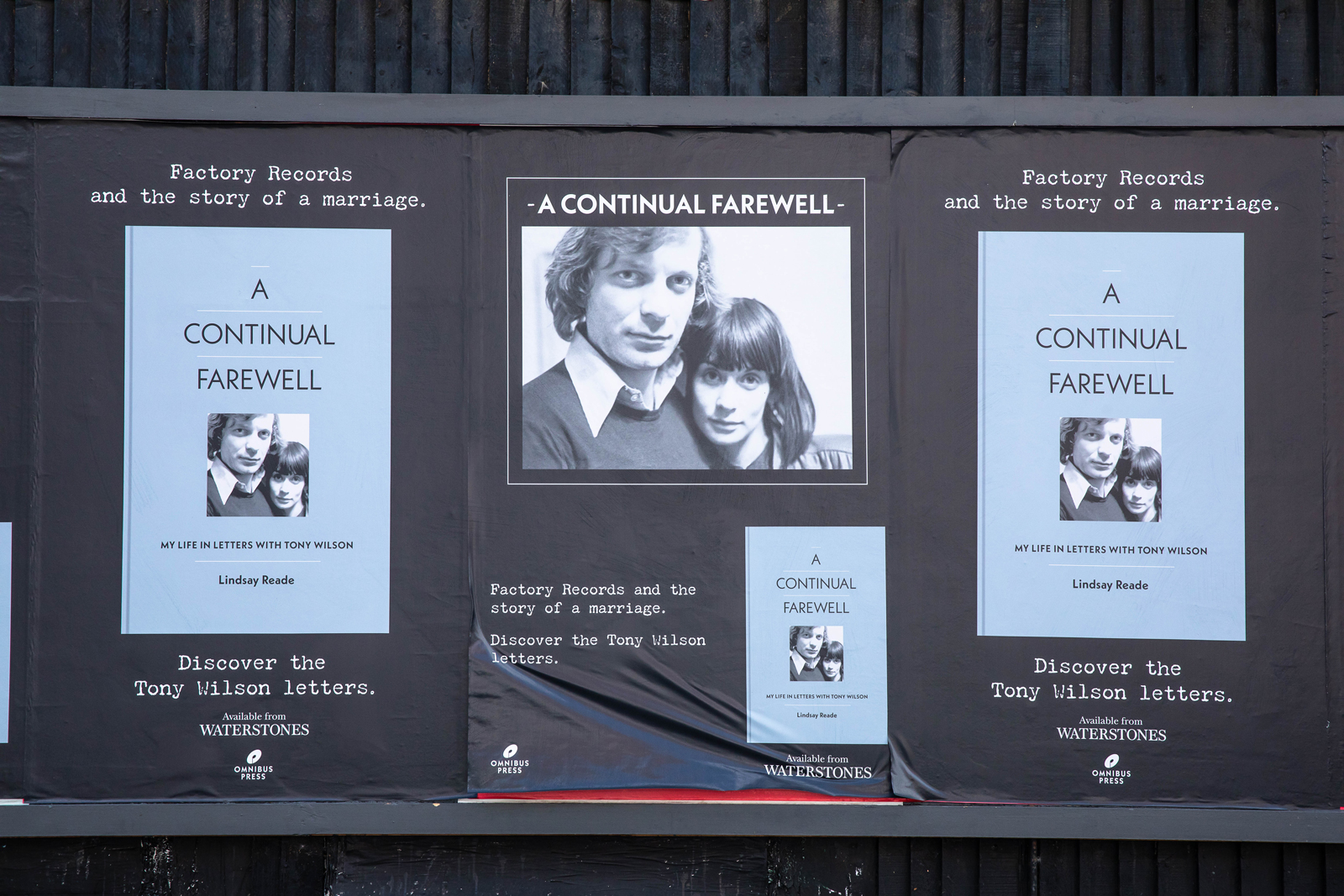

A CONTINUAL FAREWELL: My Life In Letters With Tony Wilson

By Lindsay Reade (Omnibus Press)

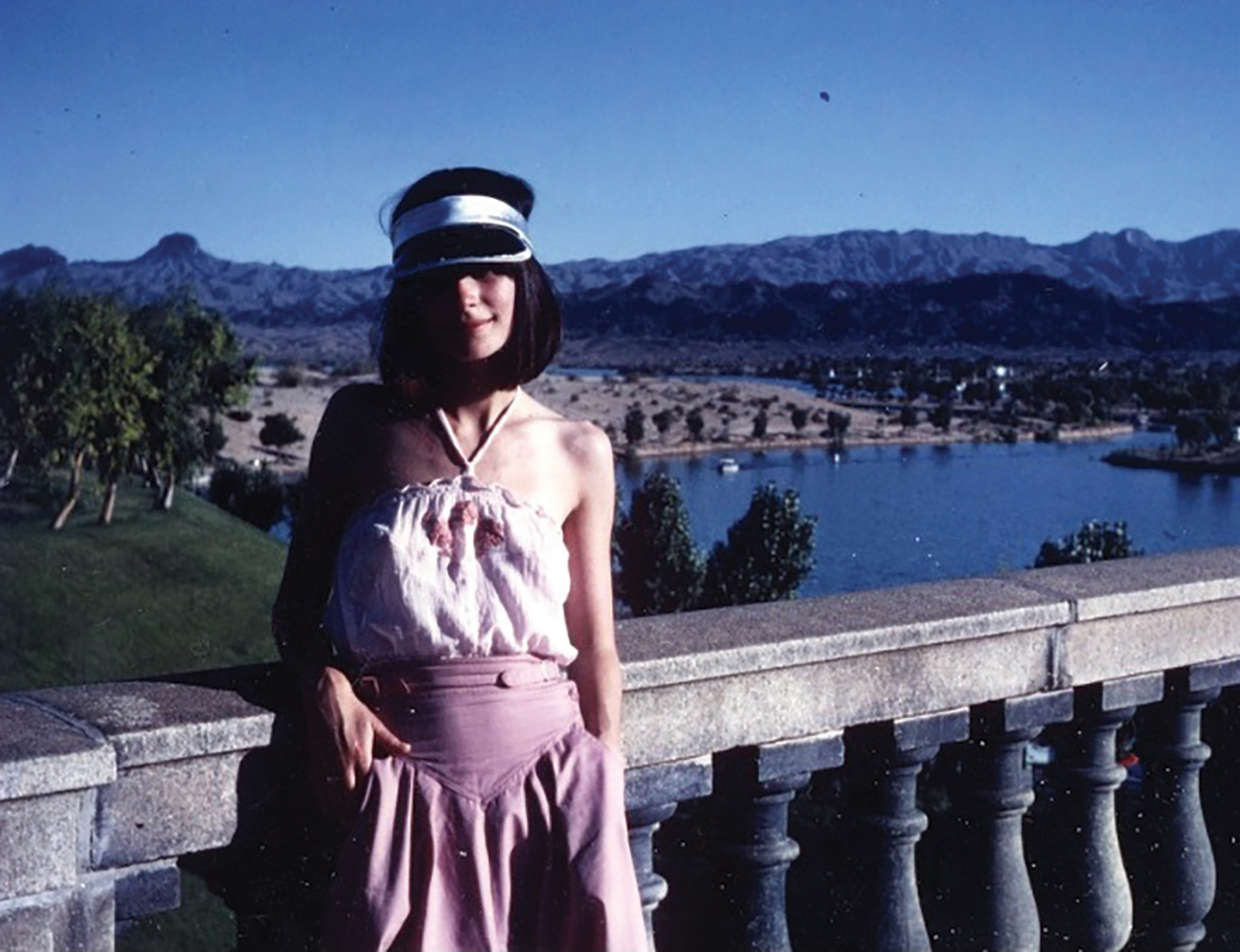

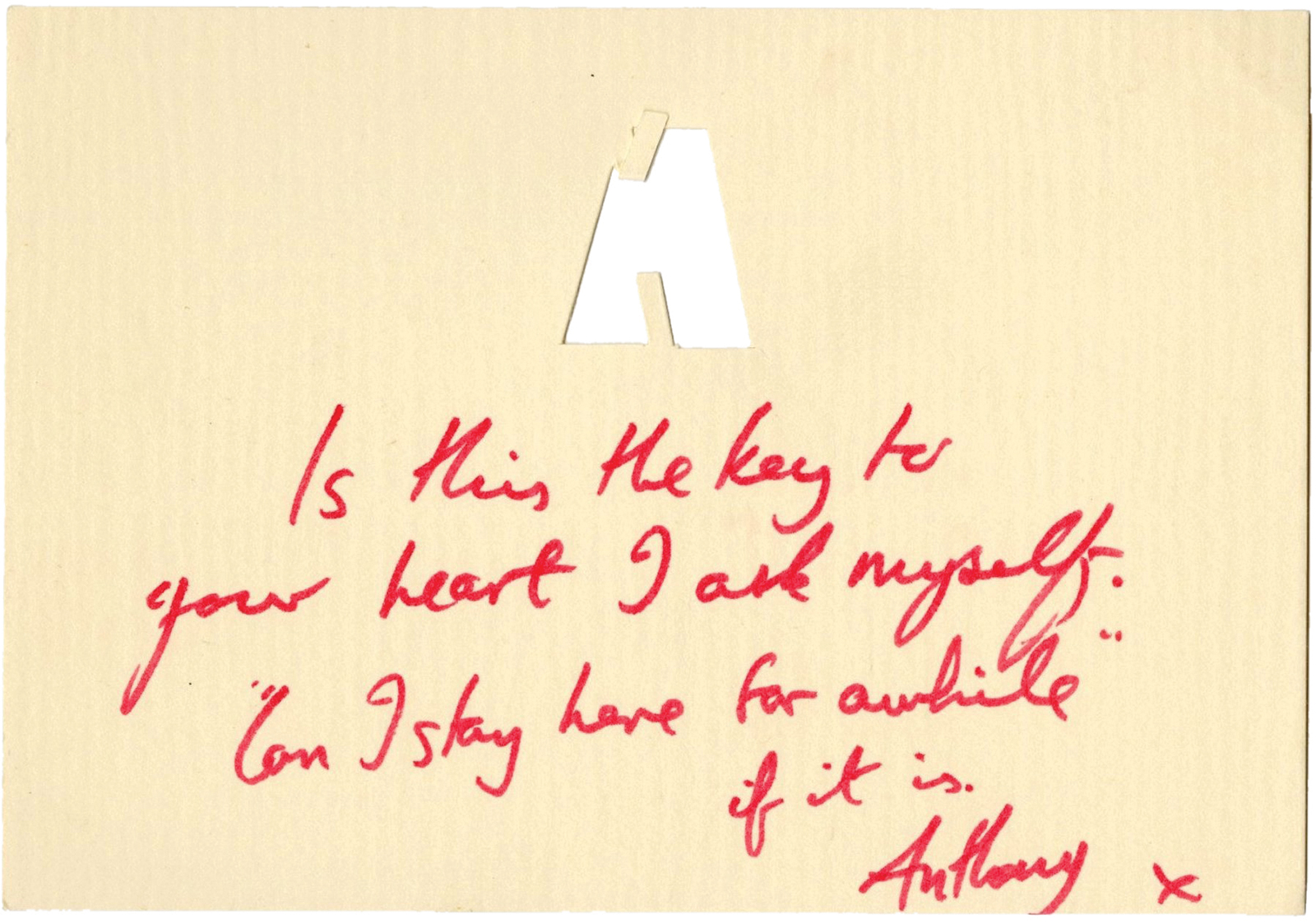

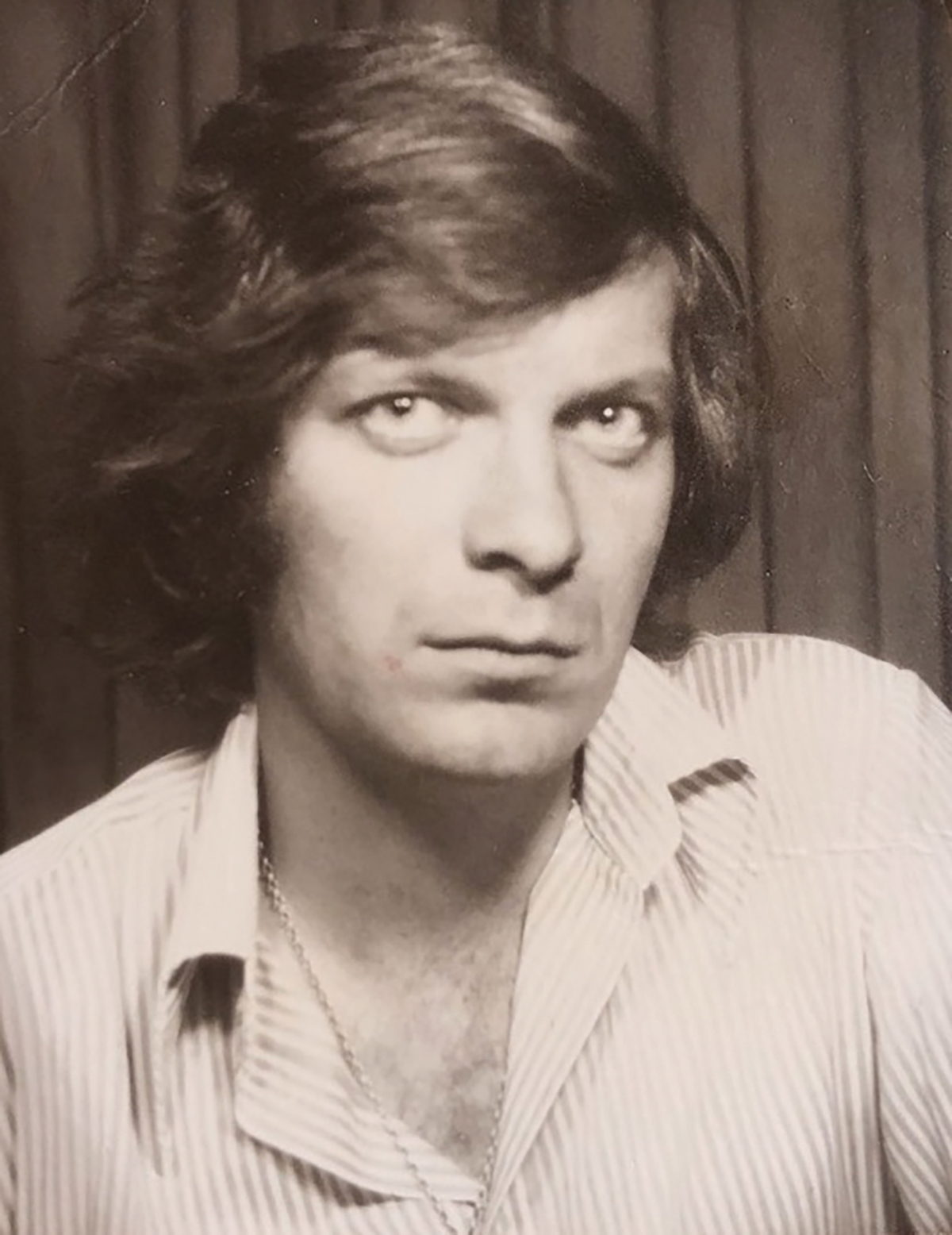

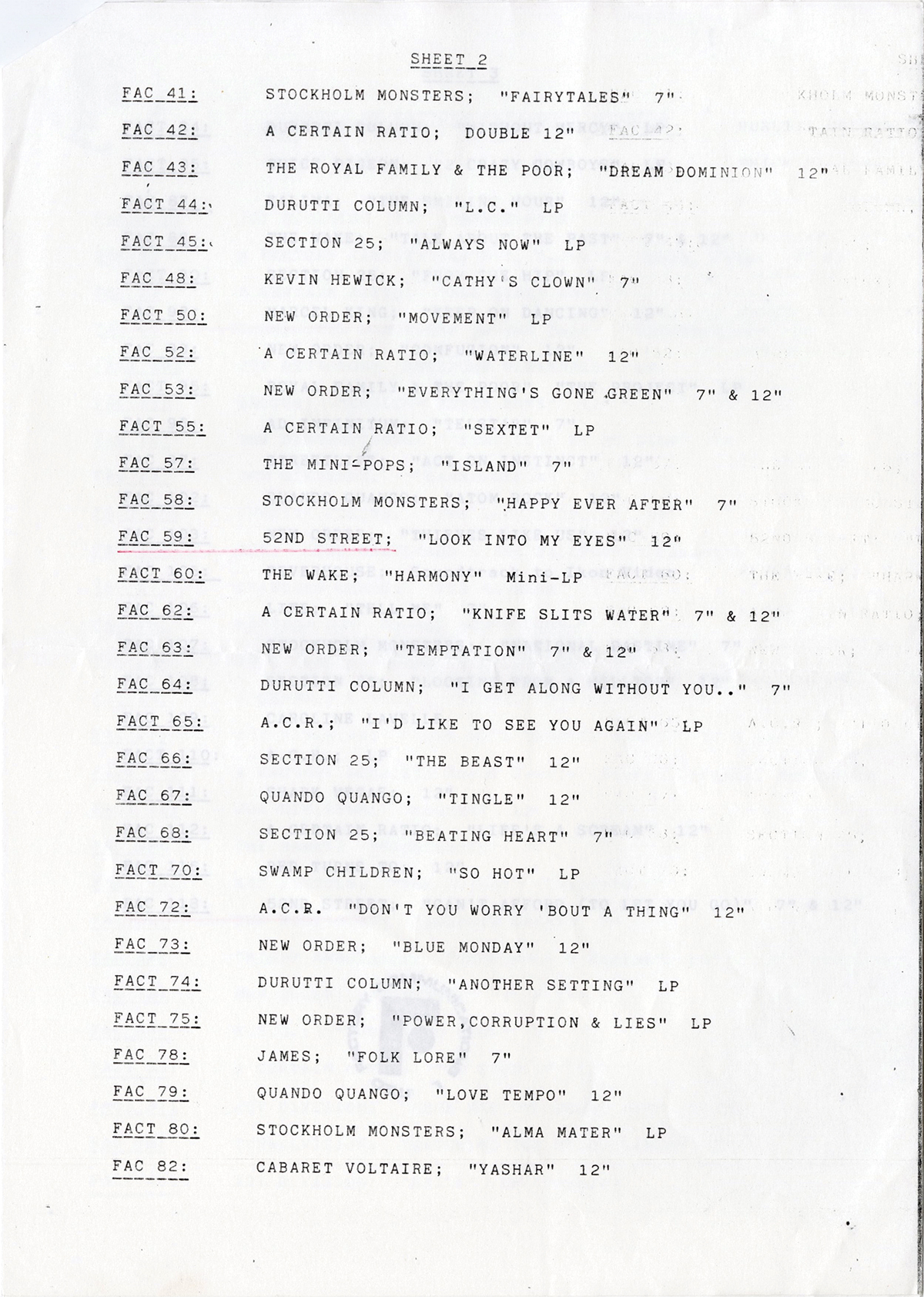

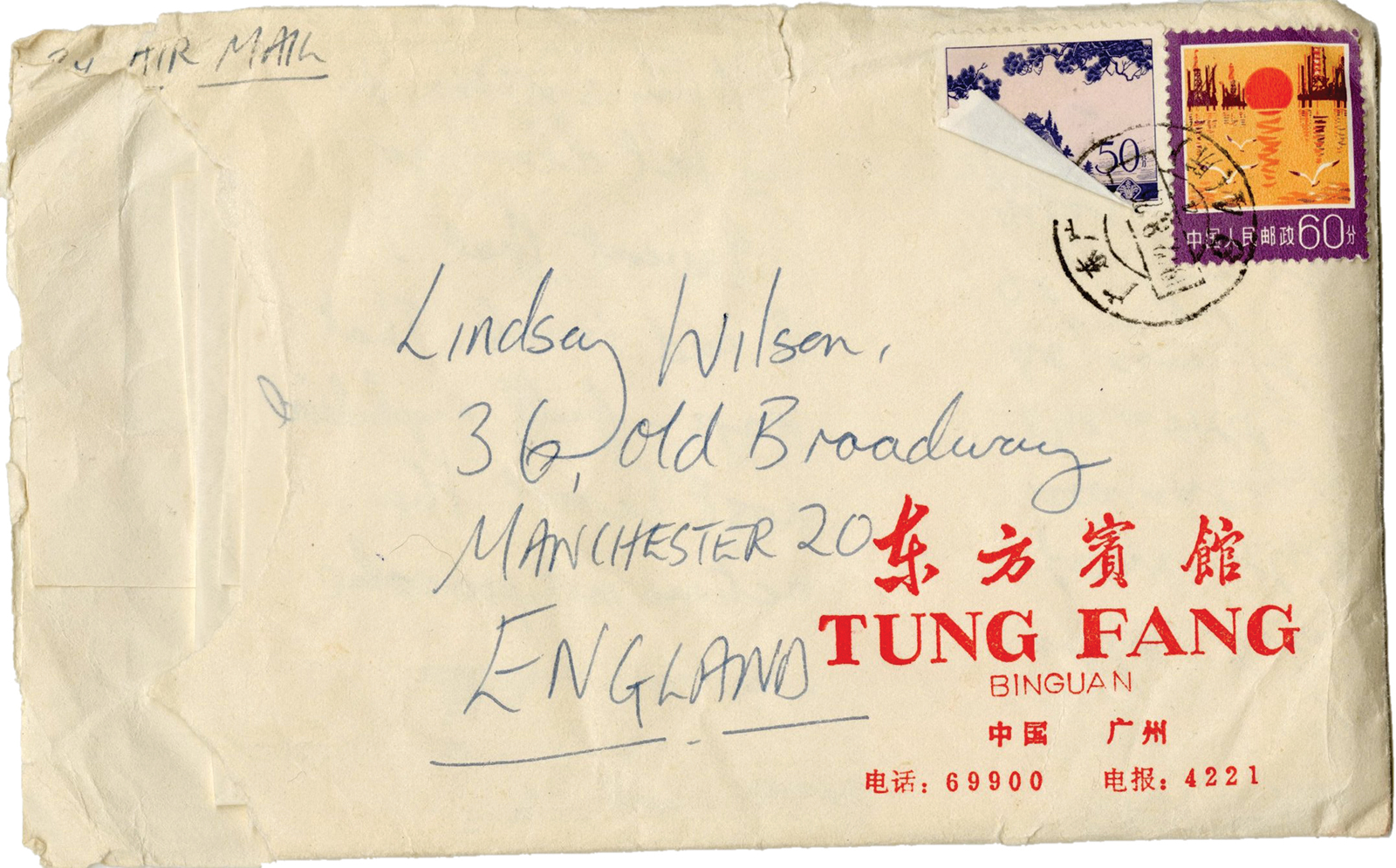

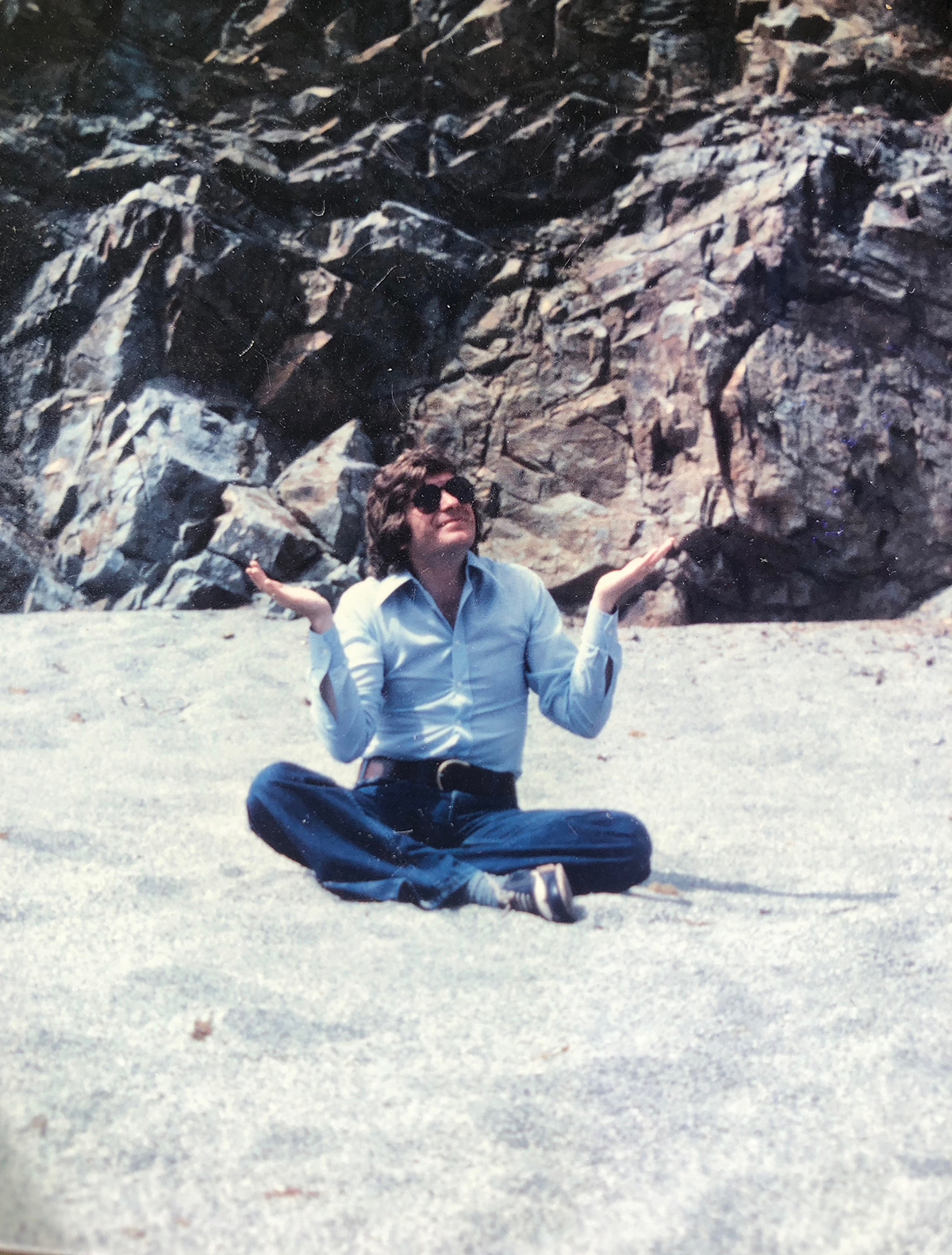

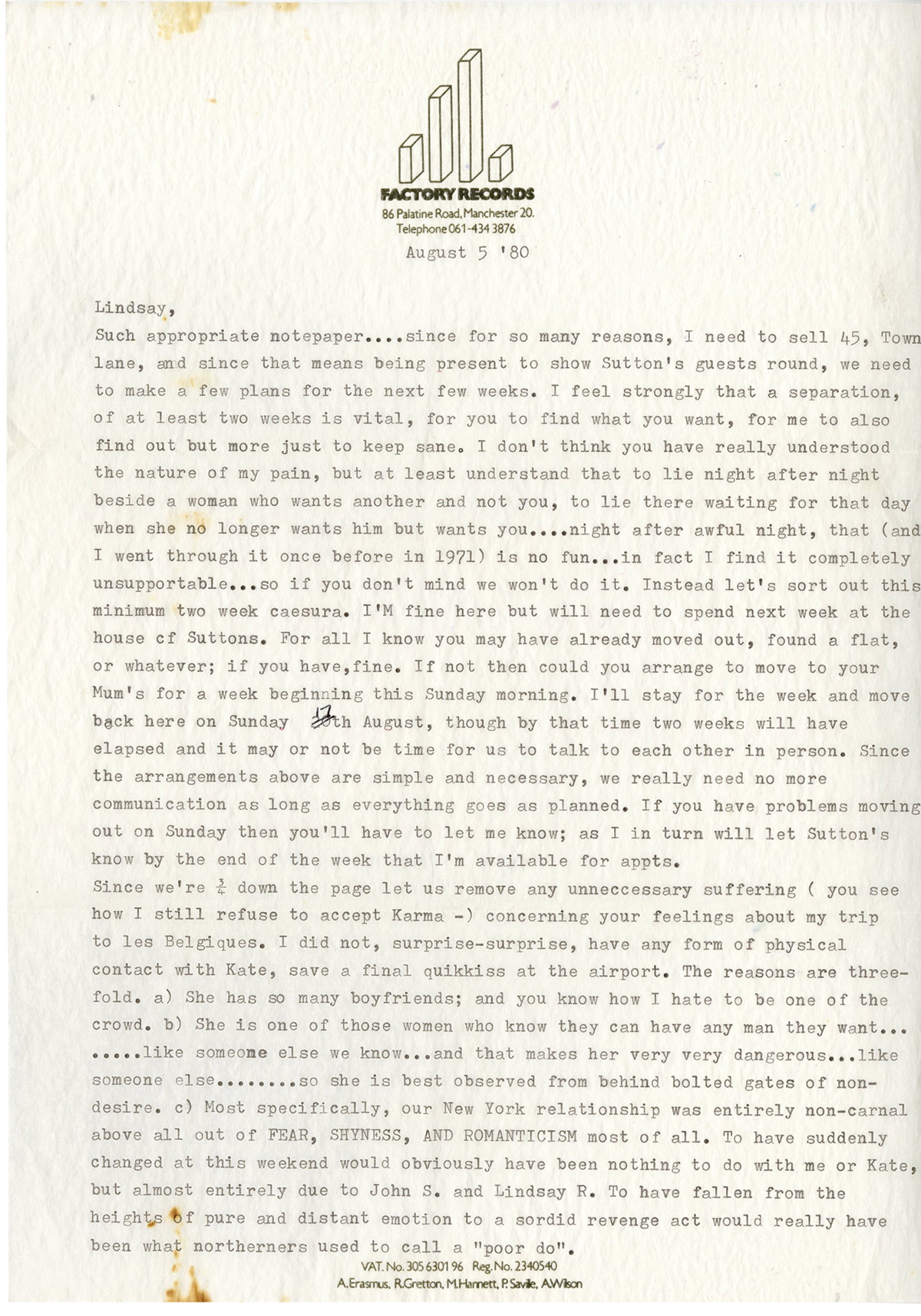

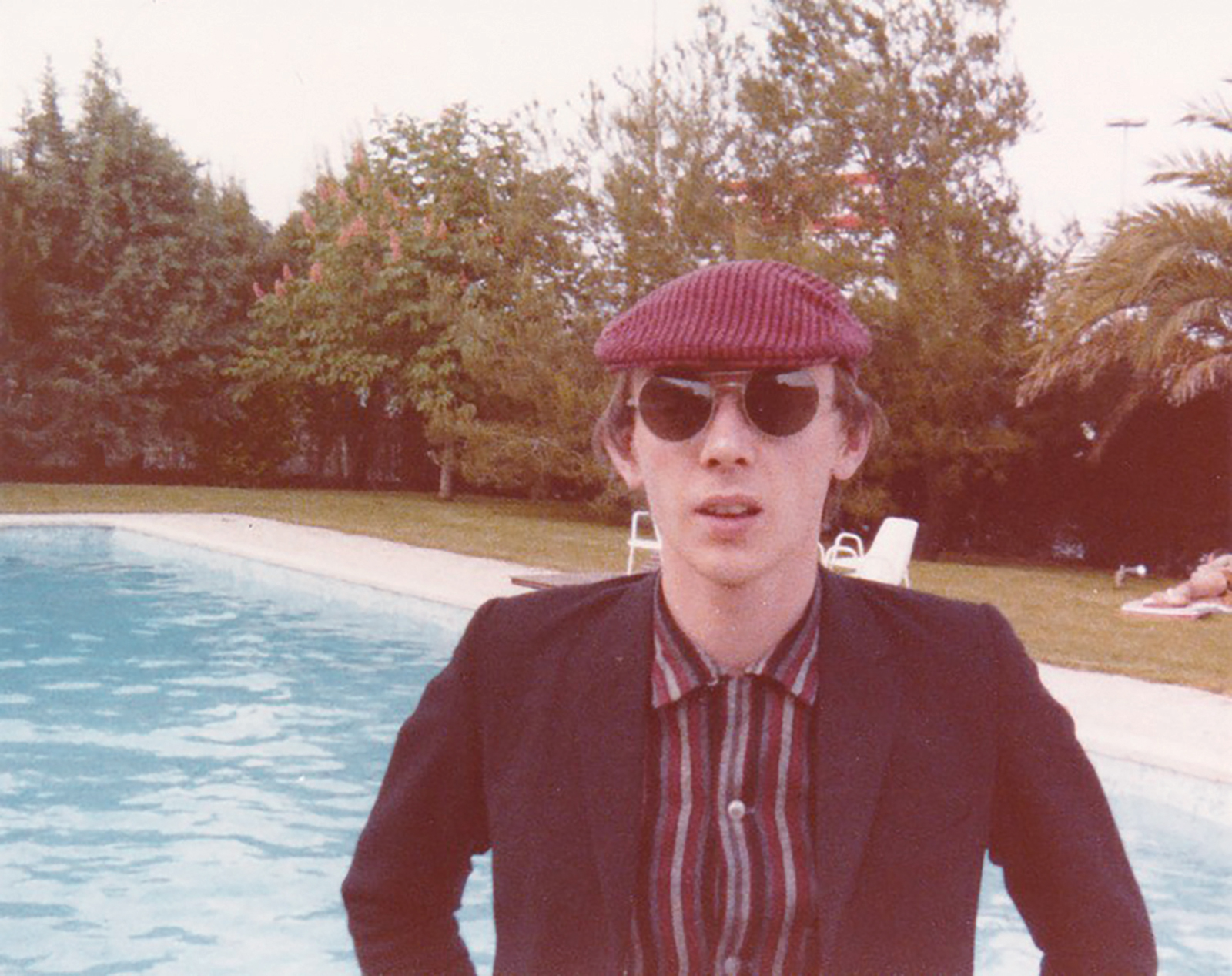

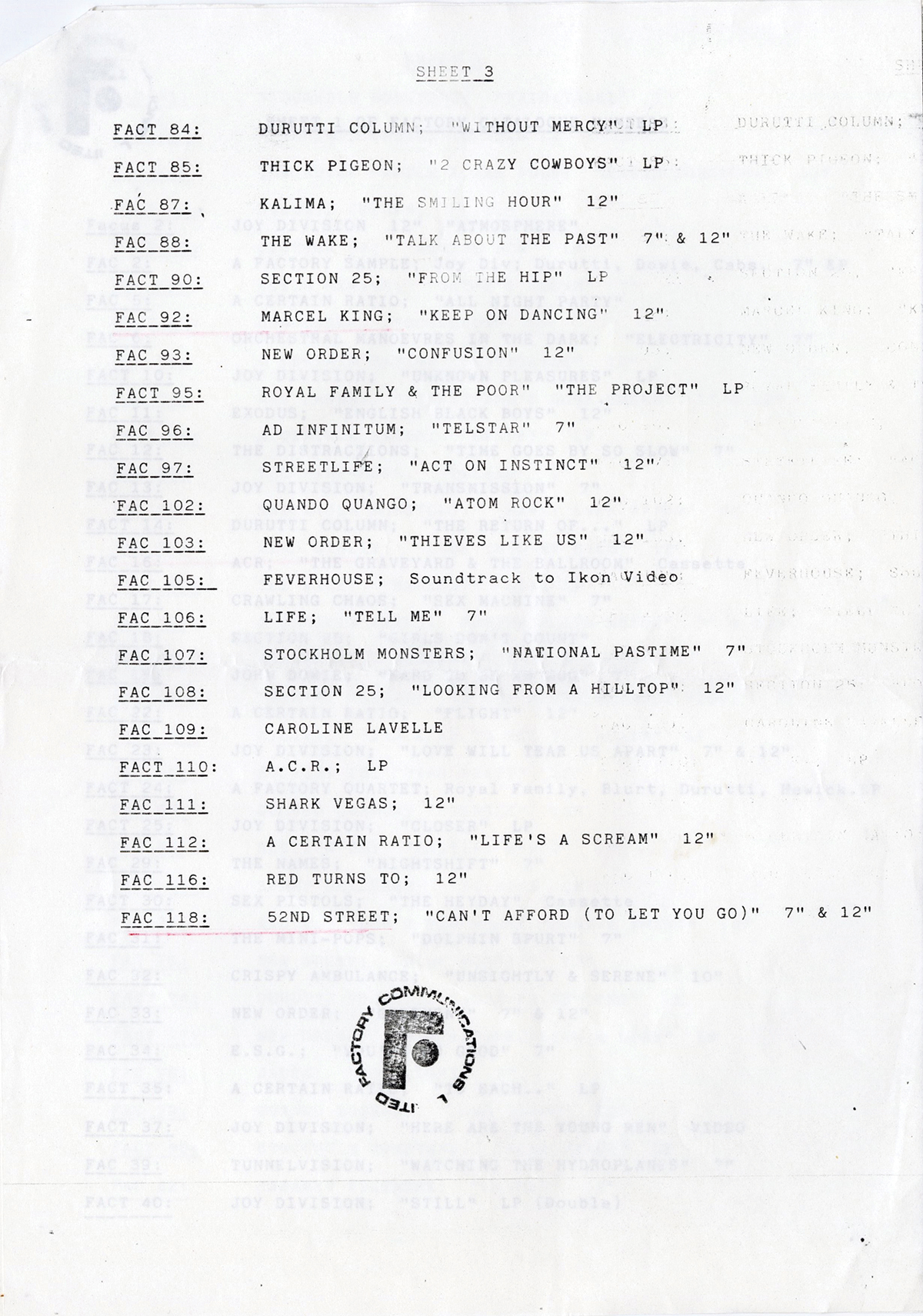

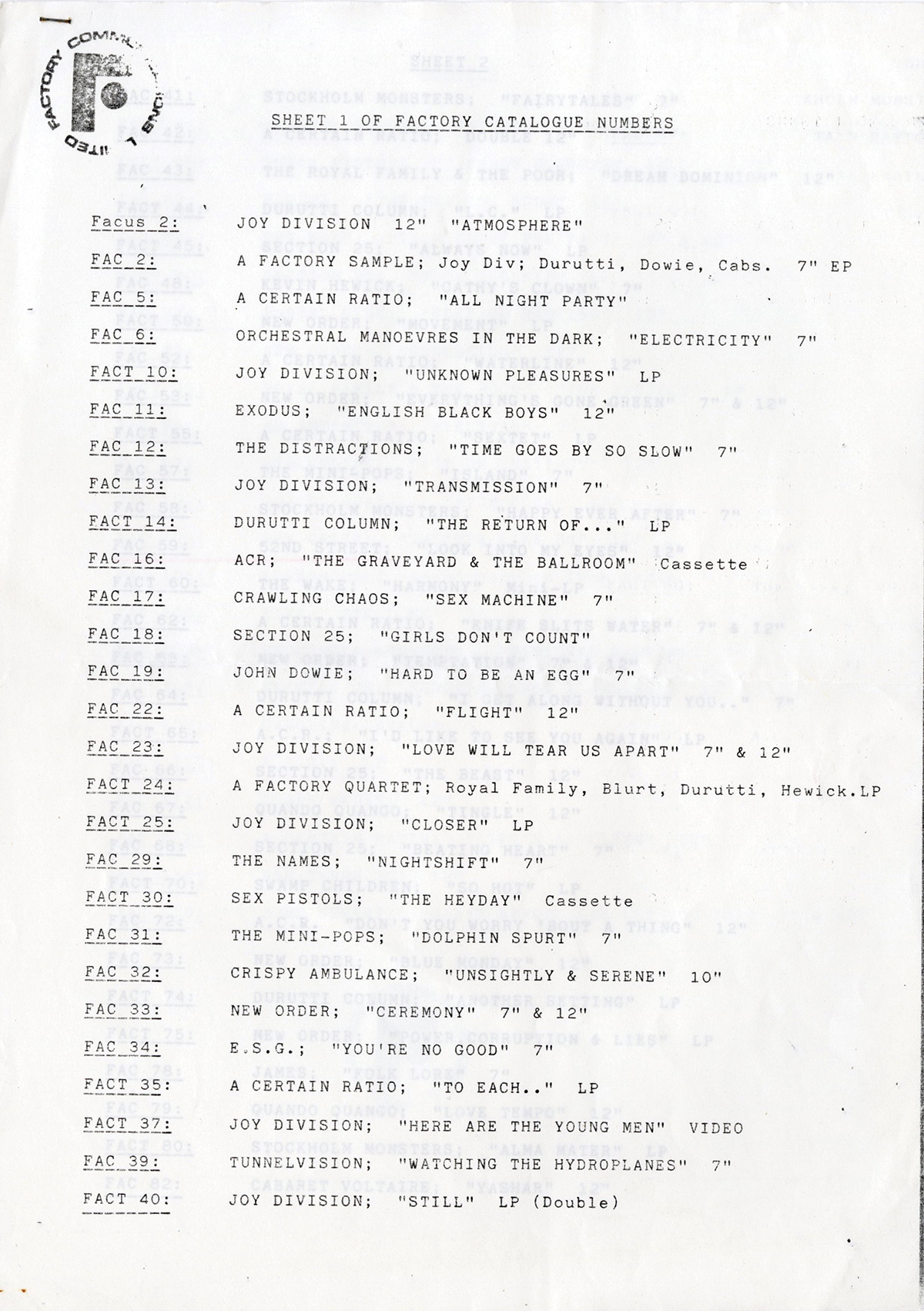

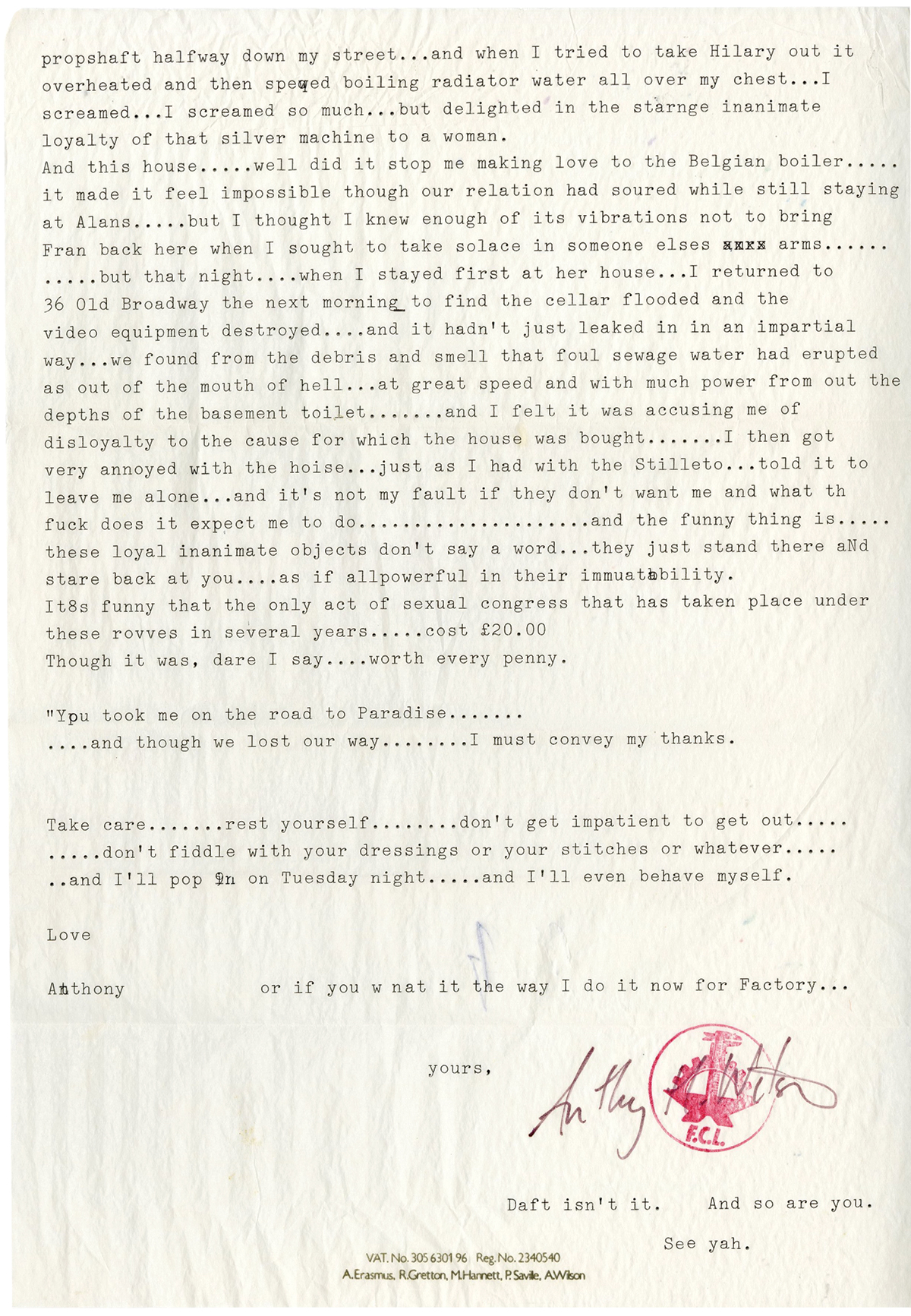

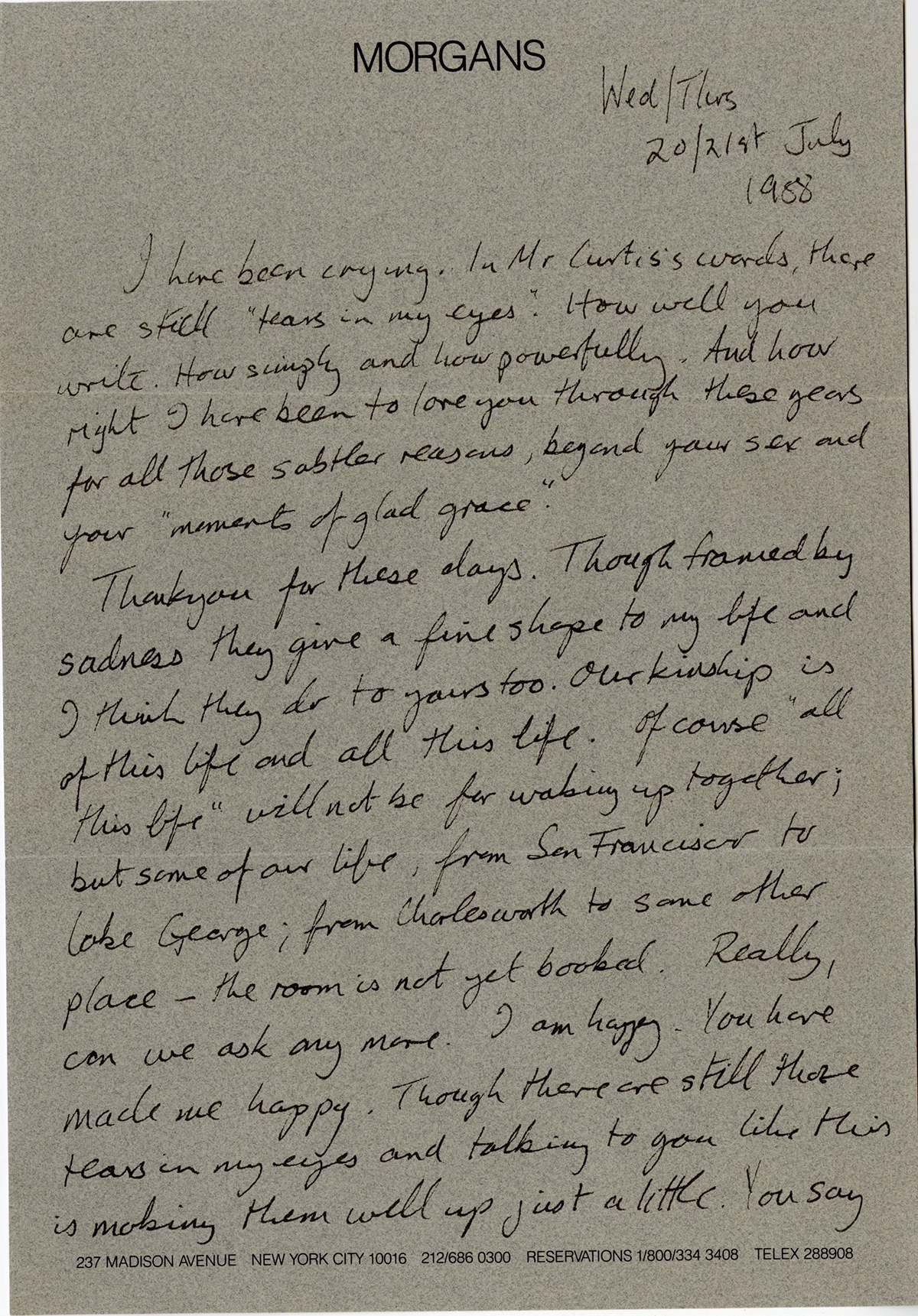

A Continual Farewell is a classic story of romance, betrayal, tragedy and, of course, sex & drugs & rock & roll – all told through 13 years worth of beautifully crafted love letters. At the heart of it, the man of letters himself was one of the great figures in the history of Mancunian music and British culture. Anthony H (Tony) Wilson was a Granada TV personality, the presenter of iconic punk/post-punk music show So It Goes and one of the creators of Manchester’s most influential record label Factory – home to Joy Division, New Order, A Certain Ratio, Durutti Column and later Happy Mondays. On the receiving end was “Lins”, Tony’s first wife Lindsay Reade, who he met in May 1976 just before his “epiphany” seeing the Sex Pistols at Manchester’s Lesser Free Trade Hall.

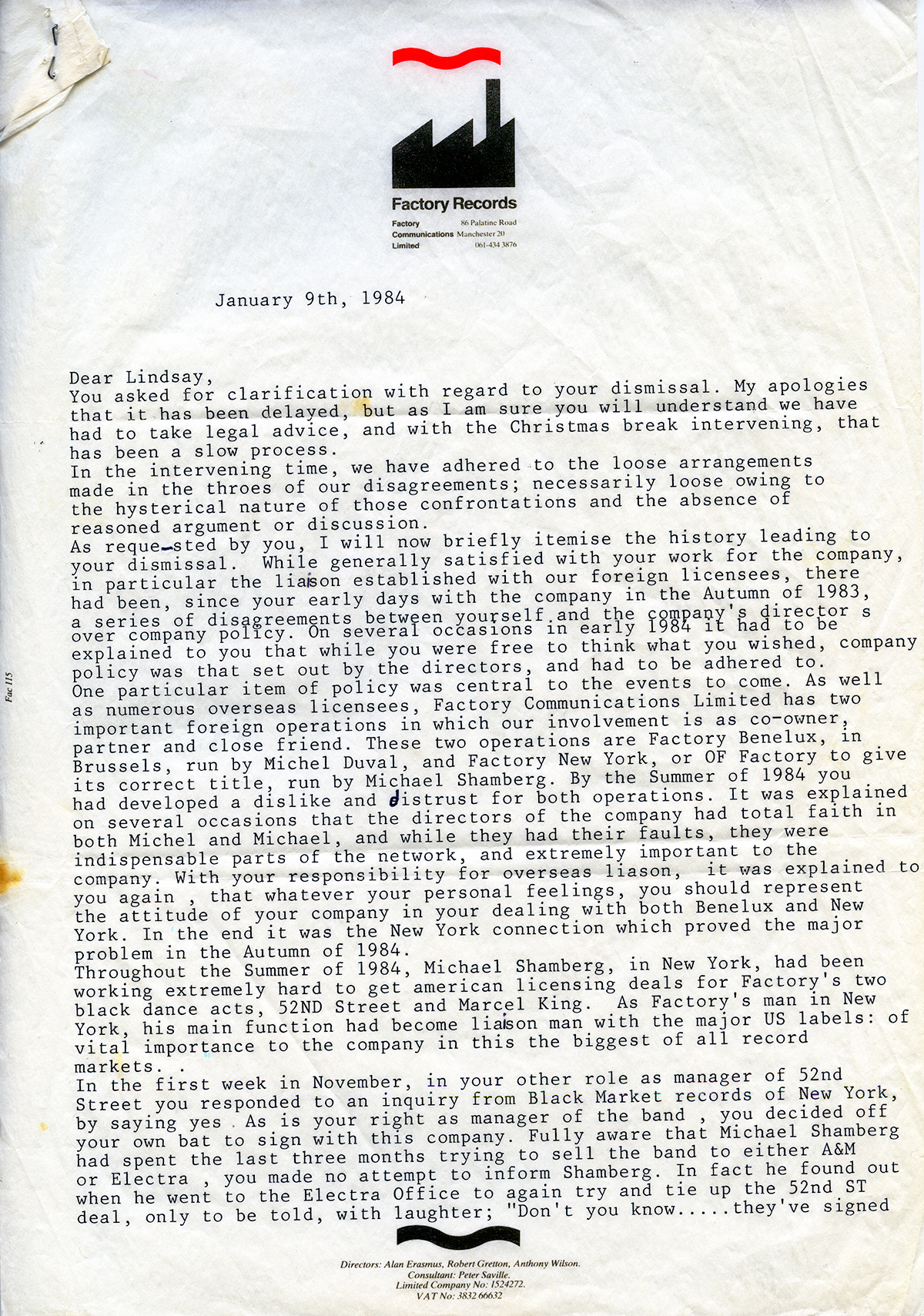

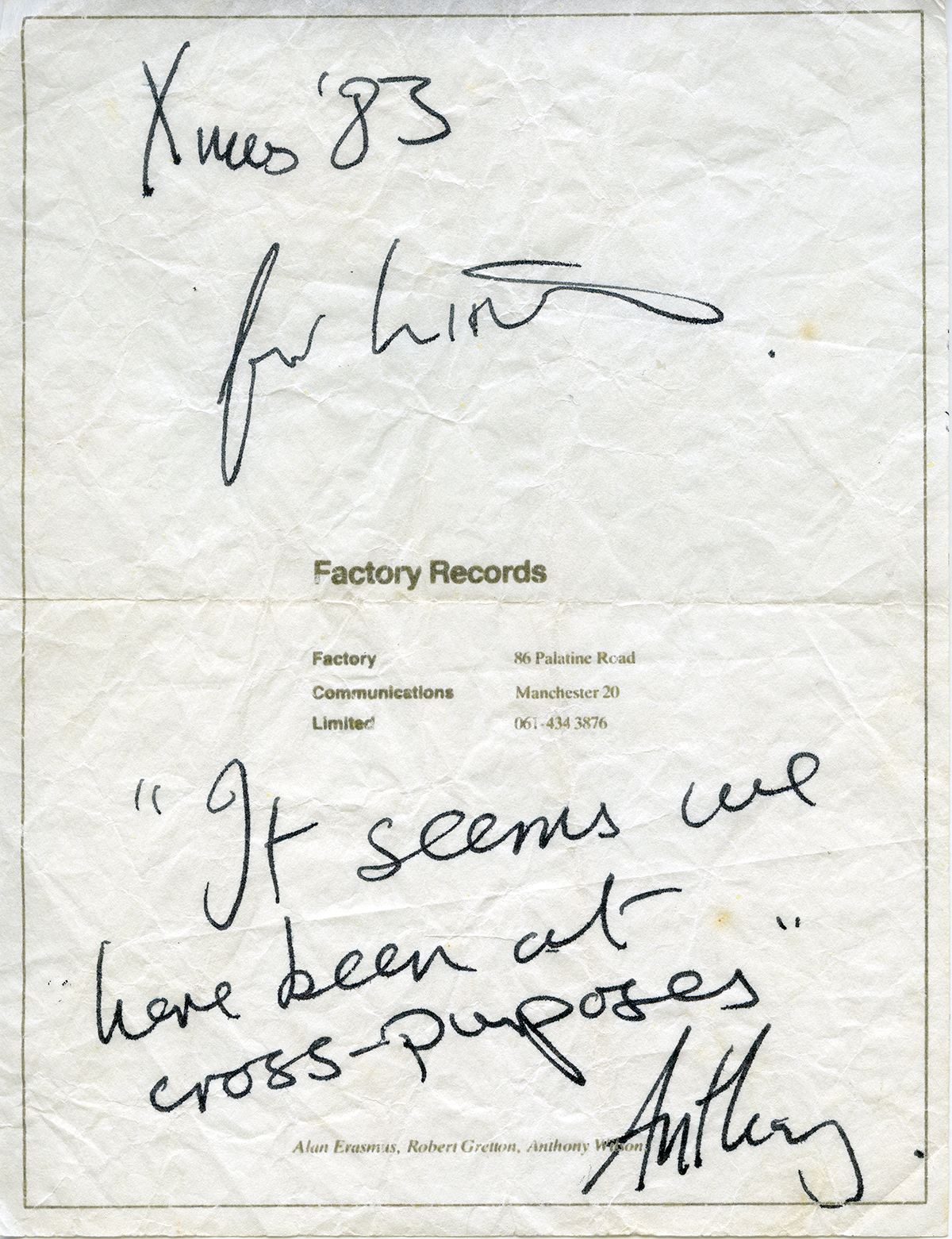

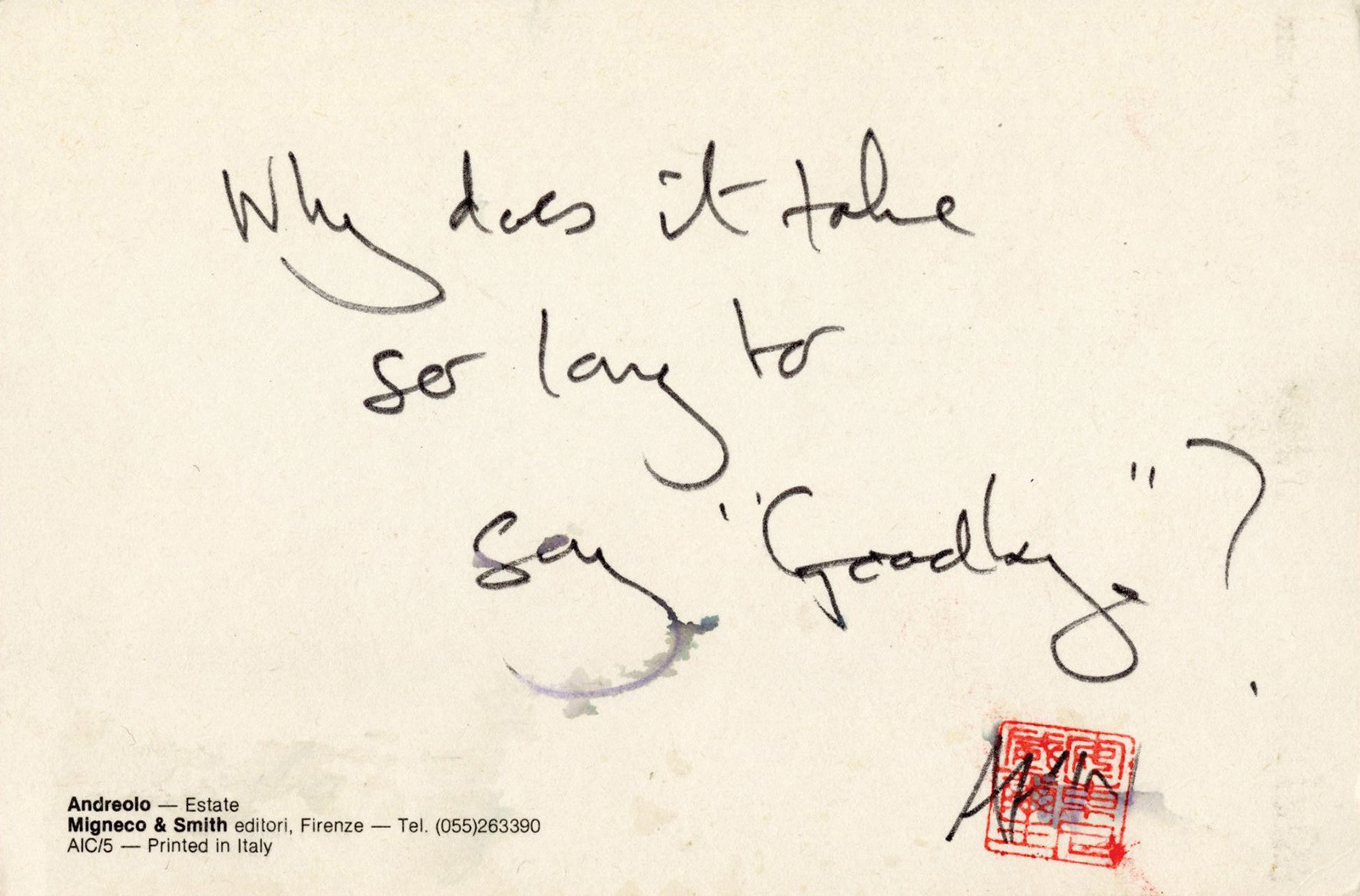

The letters tell the true story of their courtship, their stormy marriage, their divorce, their subsequent clandestine liaisons and their eventual reconciliation before Wilson’s early death at 57 in August 2007. Along the way we’re given access to the private and romantically poetic thoughts of Anthony H as he tries to balance his television career with the rise of Joy Division, the suicide of Ian Curtis, the success of Factory Records through New Order and Factory’s culturally significant by-products, the Hacienda club and eventually Madchester.

During the course of their marriage which, by these accounts, was rocky and plagued with jealousy from the start, it becomes clear that Tony’s old-fashioned approach to their relationship fuels Lindsay’s insecurities. All five directors of Factory Records were men even though Tony used his and Lindsay’s money to fund early releases, including Joy Division’s ‘Unknown Pleasures’: “Tony and I never had children but we did give birth to Factory”. In her commentary, Lindsay writes that “as Tony’s lover I felt like a goddess but as his wife, a doormat”. Later in the marriage she says she’d “continued to be a household slave which was utterly unappreciated by him”. And her jealousy takes hold when Blondie make their TV debut on Granada Reports in November 1977 performing ‘Rip Her To Shreds’. Lindsay writes of Debbie Harry “she was the most beautiful creature, super talented and Tony clearly worshipped her”.

06.09.24

Words by