Partnerships

Going DIY Deep with Slowdive

Slowdive bassist Nick Chaplin hopped on a Zoom to chat about their roots in DIY culture, the influence of their hometown Reading and brand new album everything is alive.

In the early 1990s Slowdive reigned supreme. Their sonic trademark of glow-drenched, reverb-soaked guitars created huge emotional worlds, inhabited by fans worldwide. The five-piece split in 1995 after three critically-acclaimed albums on the iconic Creation Records – and reformed in 2017 with the epic Slowdive.

Their fifth album, everything is alive, began with vocalist and guitarist Neil Halstead playing around with modular synths in his Cornish home. “That was the direction he started in,” says bassist Nick Chaplin, “but unfortunately for him, when everyone else gets in the room it all tends to go back to the more regular Slowdive Sounds. There’s a bit of an influence of both. I think it’s turned out pretty well.”

It’s an understated perspective on the big sounds that Slowdive deal in. It’s evocative music, full of late night tenderness and strung-out early morning atmospherics. The sound, says Chaplin, goes right back to their earliest recordings. “Back in 1989 we were influenced by people like The Primitives and Jesus and the Mary Chain: short pop songs and noisy guitars. Rachel and I were goths when we were teenagers, so we had that atmospheric side to the music we liked to listen to. When we came up with ‘Avalyn’ – the almost instrumental track on the first EP – we all looked at each other in the studio and said ‘OK, this is not The Primitives anymore’.”

07.09.23

Words by

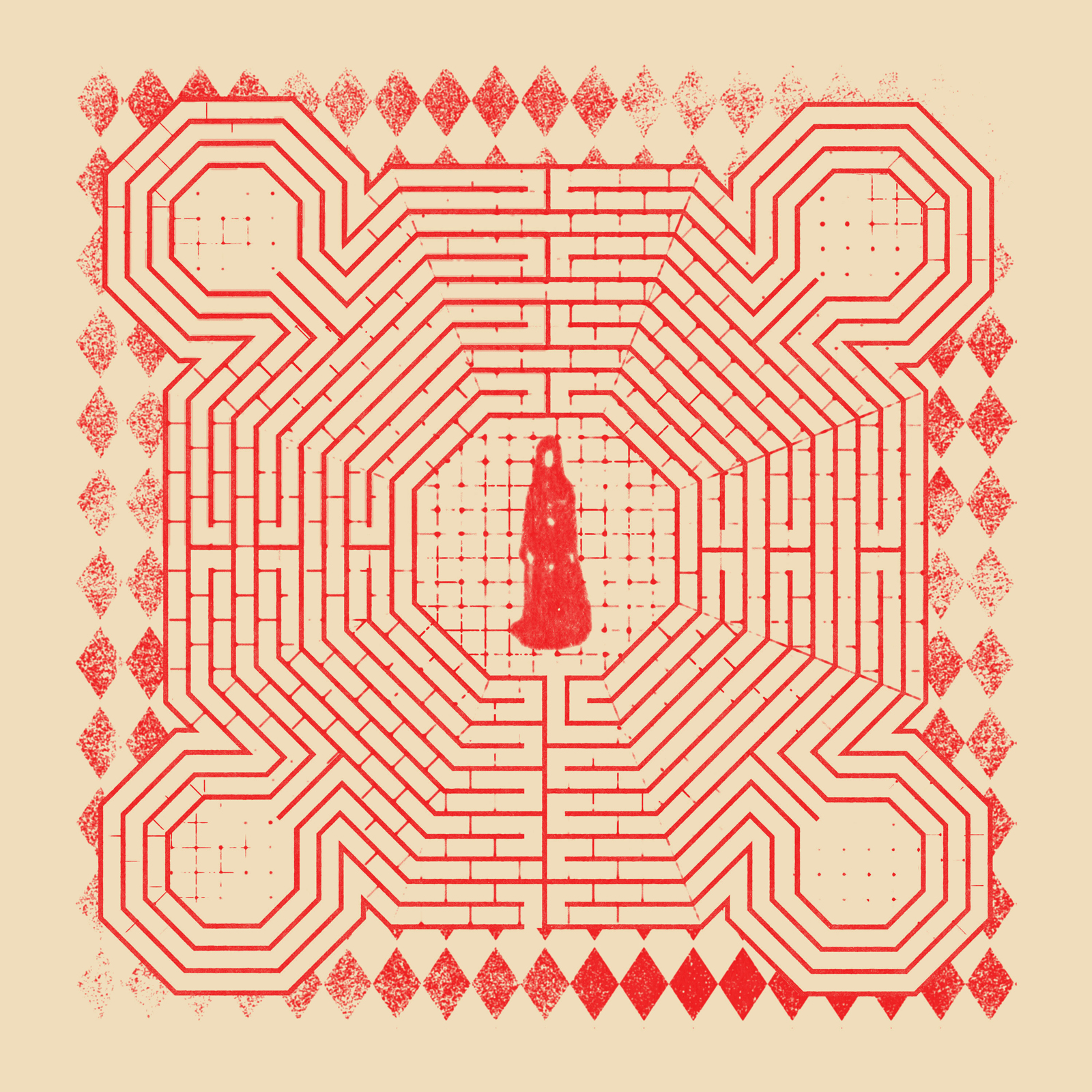

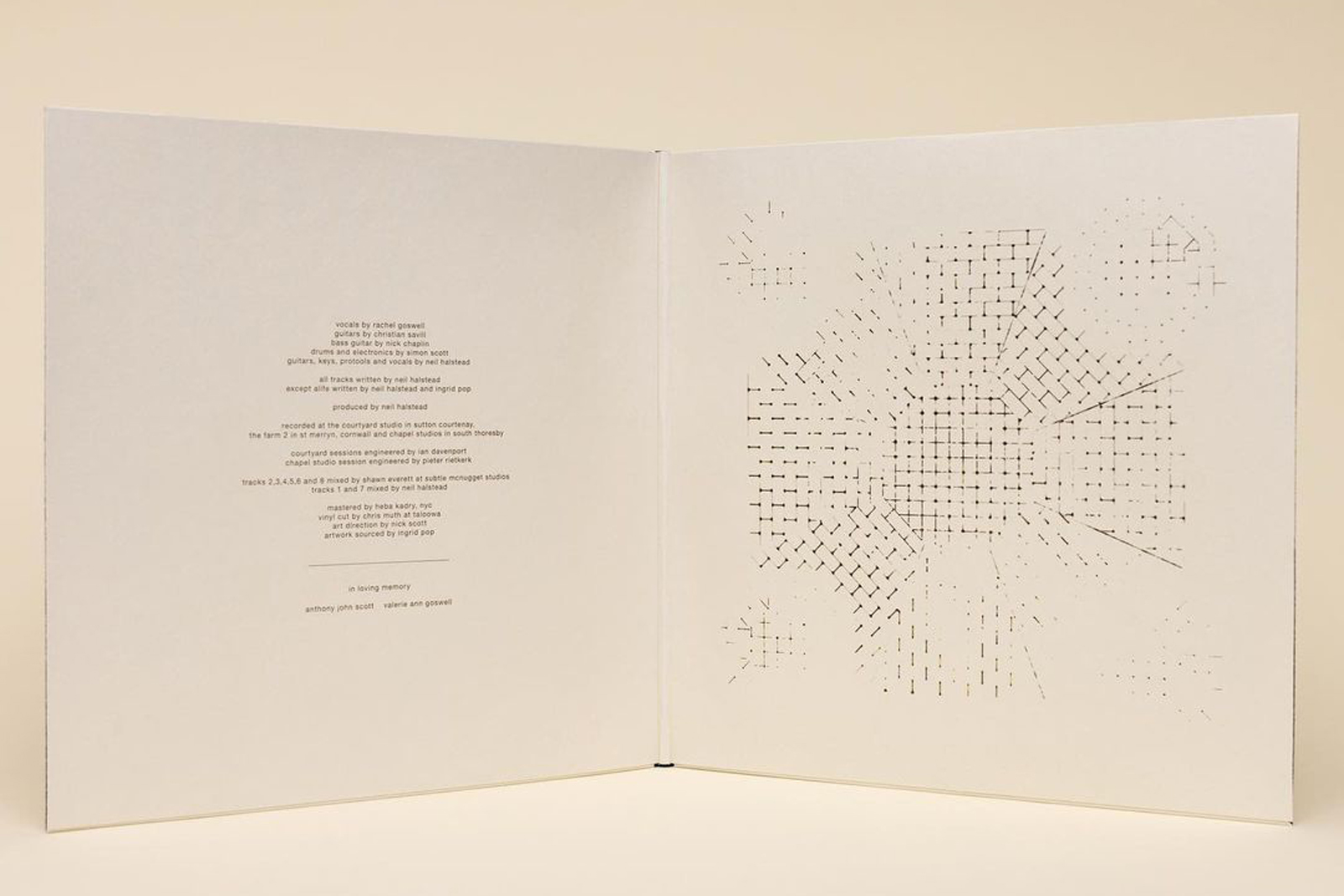

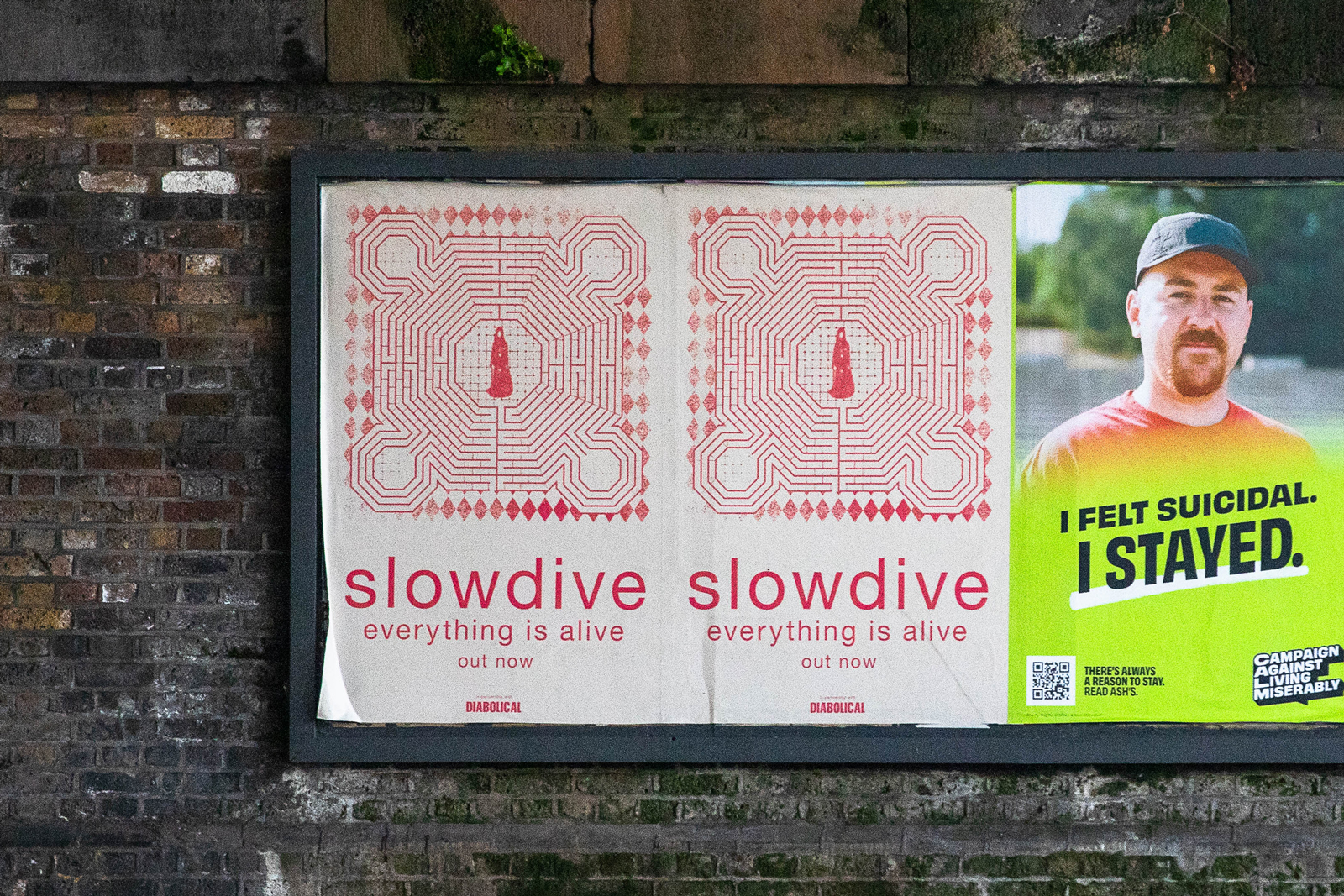

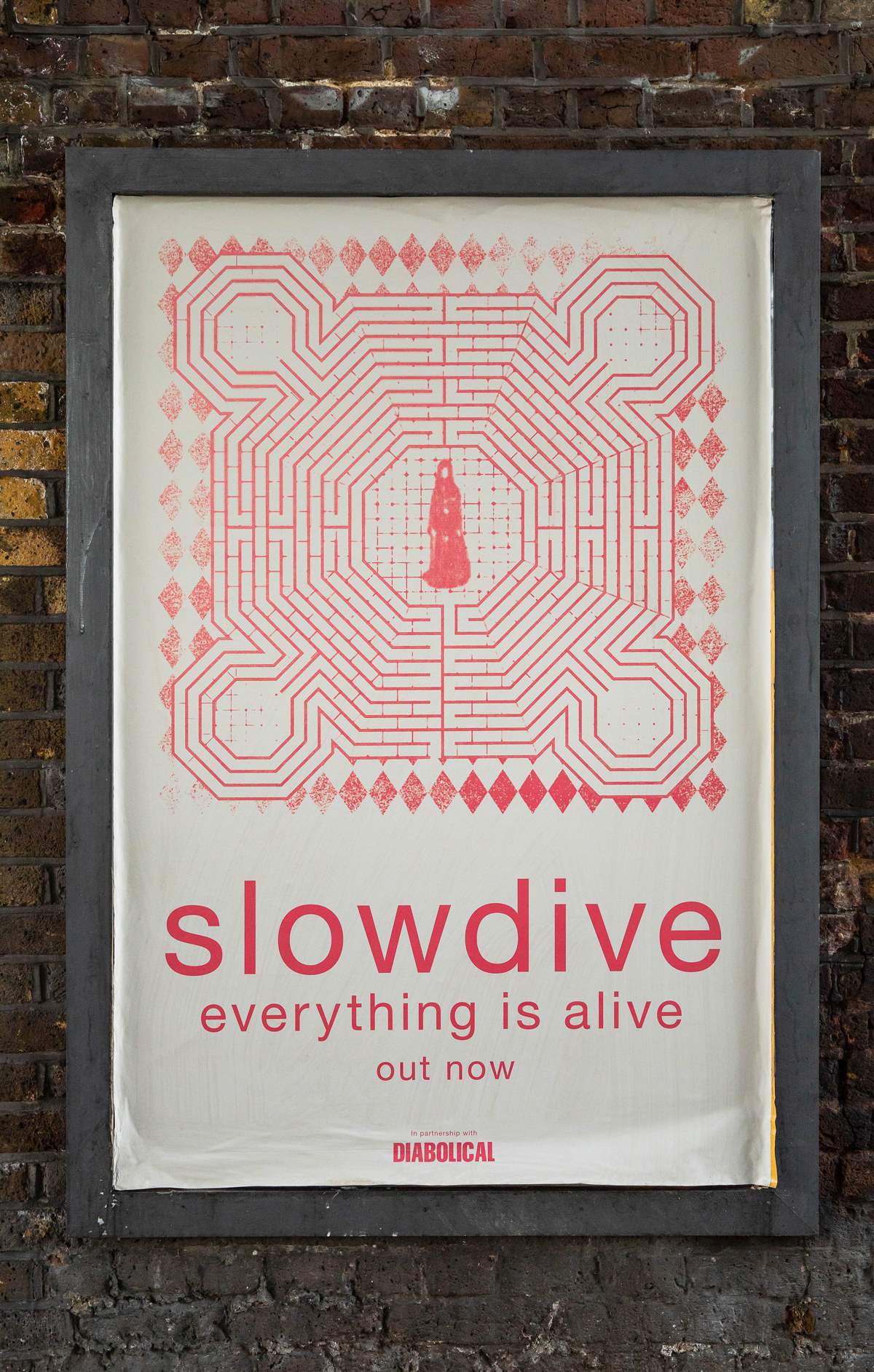

everything is alive by Slowdive

everything is alive by Slowdive

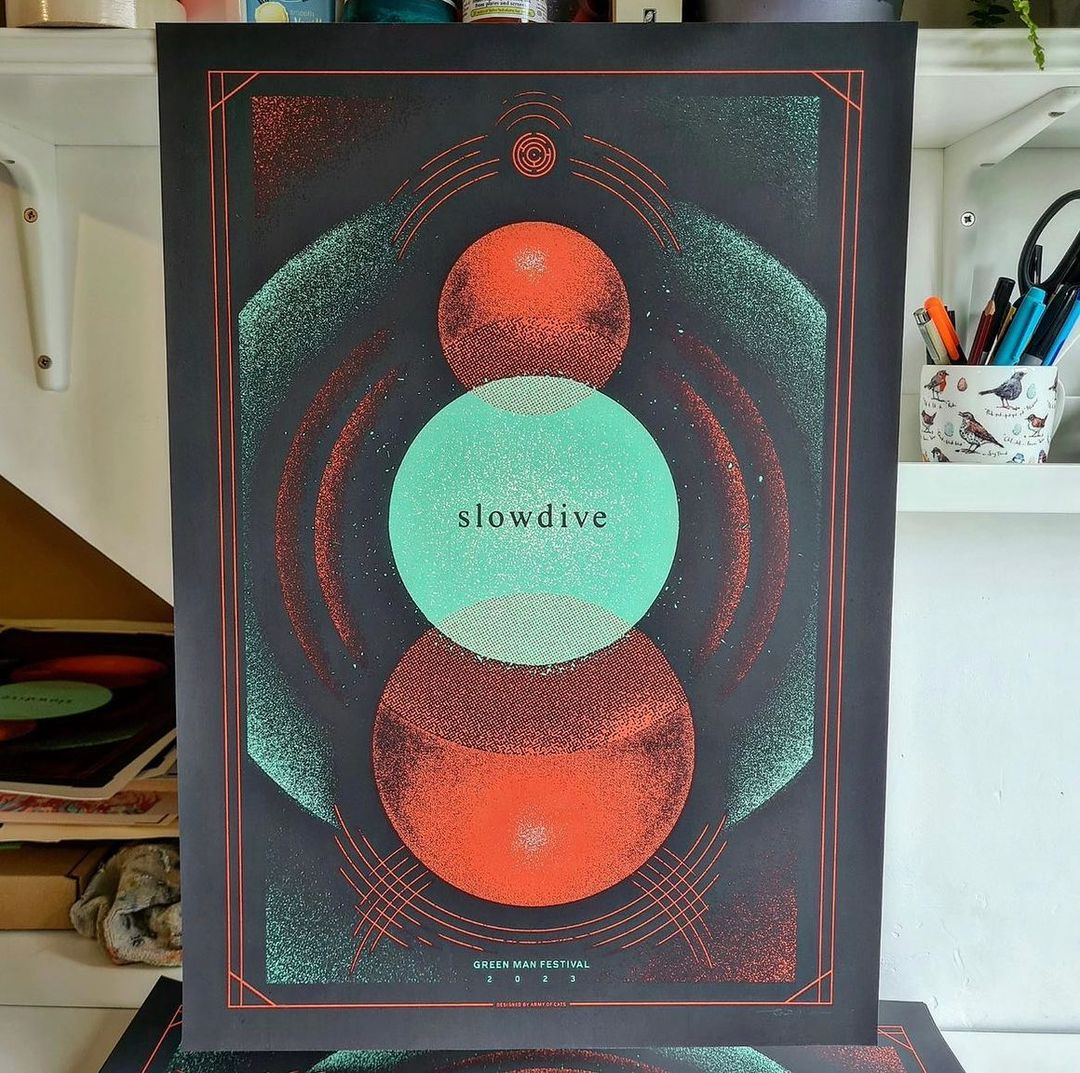

Green Man Festival Poster

Green Man Festival Poster

Photo Credit: Ingrid Pop

Photo Credit: Ingrid Pop

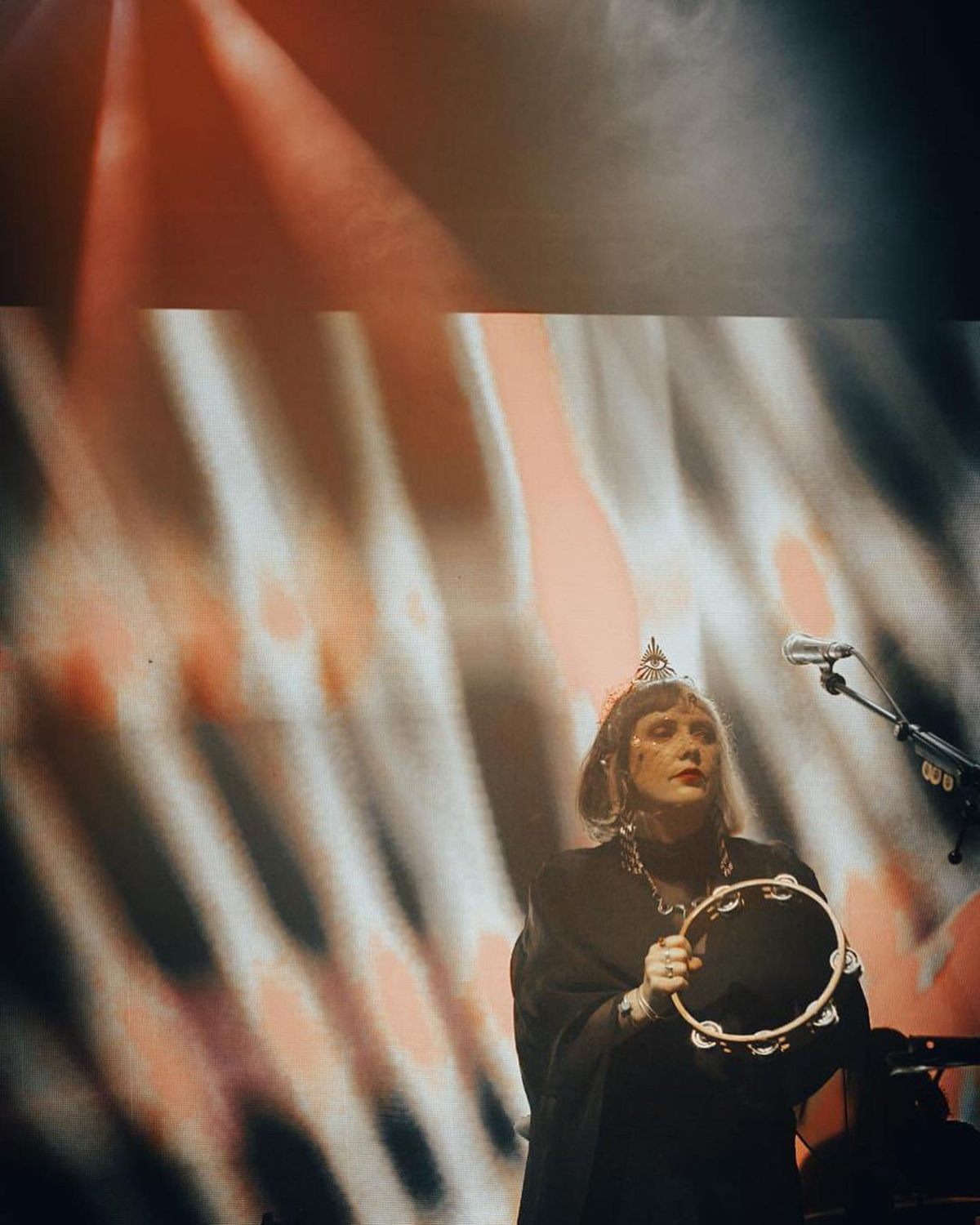

Photo by @mikestreetbike

Photo by @mikestreetbike

Photo Credit: Parri Thomas

Photo Credit: Parri Thomas