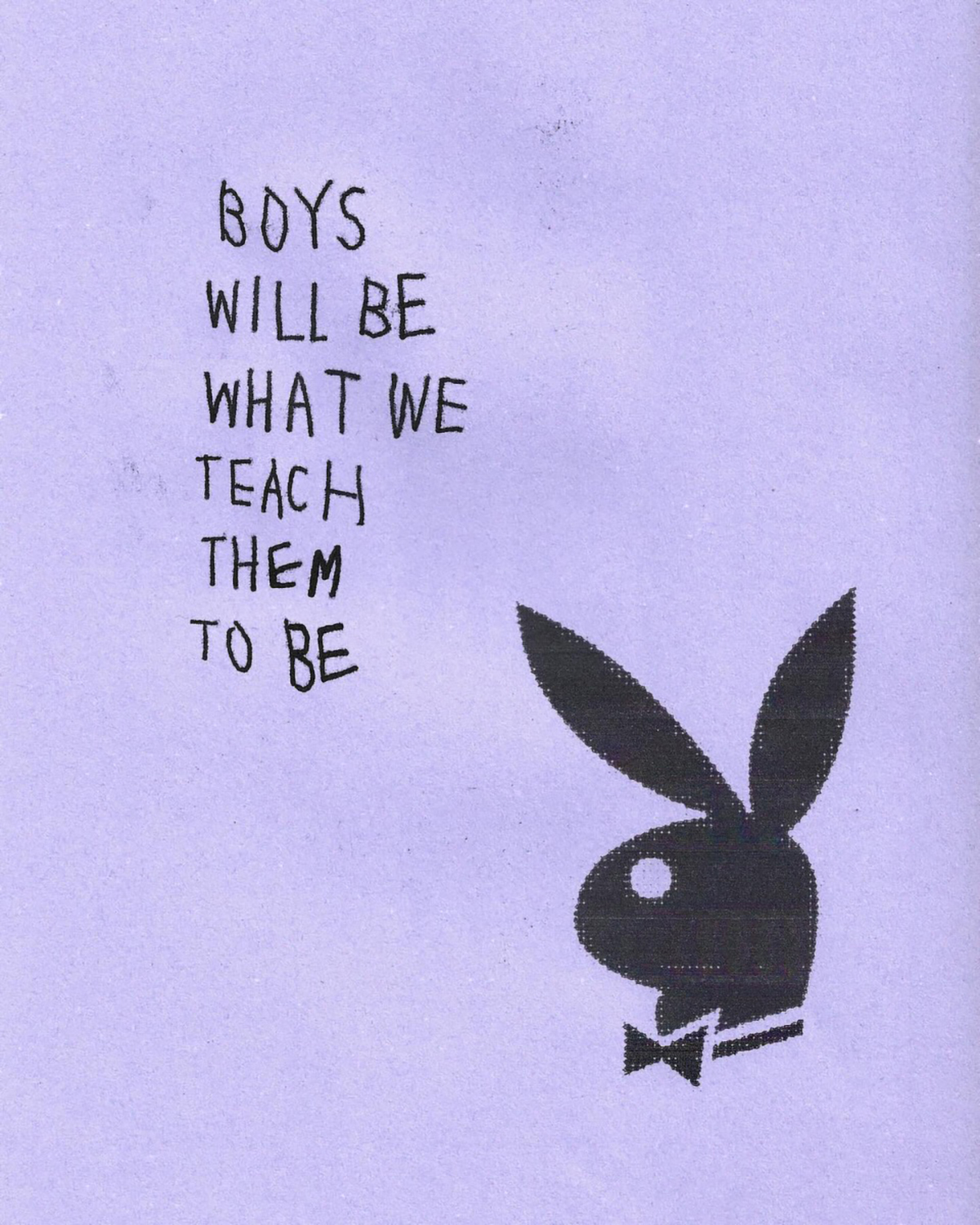

Another key theme in Fruit II is the masc vs femme conundrum that so many queer people grow up navigating. In what ways have you personally felt that tension, and how has it found its way into your work?

Yeah, that’s something I’ve always struggled with. I was quite a naturally feminine teenager, and Glasgow doesn’t exactly pull any punches. You get it thrown at you. Society made boys think being feminine was wrong, that it wasn’t something to show or be proud of.

It’s like you’ve spent so long trying to suppress it that it doesn’t always come out naturally. I might present a bit more “masc” in the gay world, but honestly, the best parts of me are the ones I got from my mum, my sister, my interests, and the environment I grew up in, and those are all feminine.

This show is about celebrating the femme. And also, taking the piss out of masculinity, especially the kind of lad culture I used to feel I had to buy into just to fit in.

There’s a newspaper clipping in the show — an old EastEnders article, reacting to the apparent ‘outrage’ at the show’s first gay kiss. Did you include this clipping to speak to how far we’ve come as a society, or does it remind us how close homophobia still is to the surface?

I’m a big EastEnders fan – it’s one of the soaps that’s stuck with me. I came across this article written by, of course, Piers Morgan, back when he was at The Sun. It was their reaction to the first gay kiss on EastEnders in the late ’80s, it was a tough read (but not surprisingly from Piers). The headline was something like: “EastBenders”, and the whole tone of it was pure outrage like, how dare this happen on TV. And that was aimed at the mainstream public.

I originally included it in the show to make a point, look how far we’ve come. It’s screenprinted onto copper, which felt symbolic: I wanted to use something hardwearing and resistant to represent the community. But since making it, things have already shifted again, and not in a good way. So now, that piece feels like more of a warning. It’s a reminder that the same hate still exists, just in different packaging. The undercurrent in that article is still there. It hasn’t gone away – it’s just been rebranded.

For the London show, I’m considering showing the version that’s been left outside for six weeks, it’s weathered, discoloured, turned a bit blue. It’s like it’s endured something. And I think that visual shift adds a new layer to the meaning.

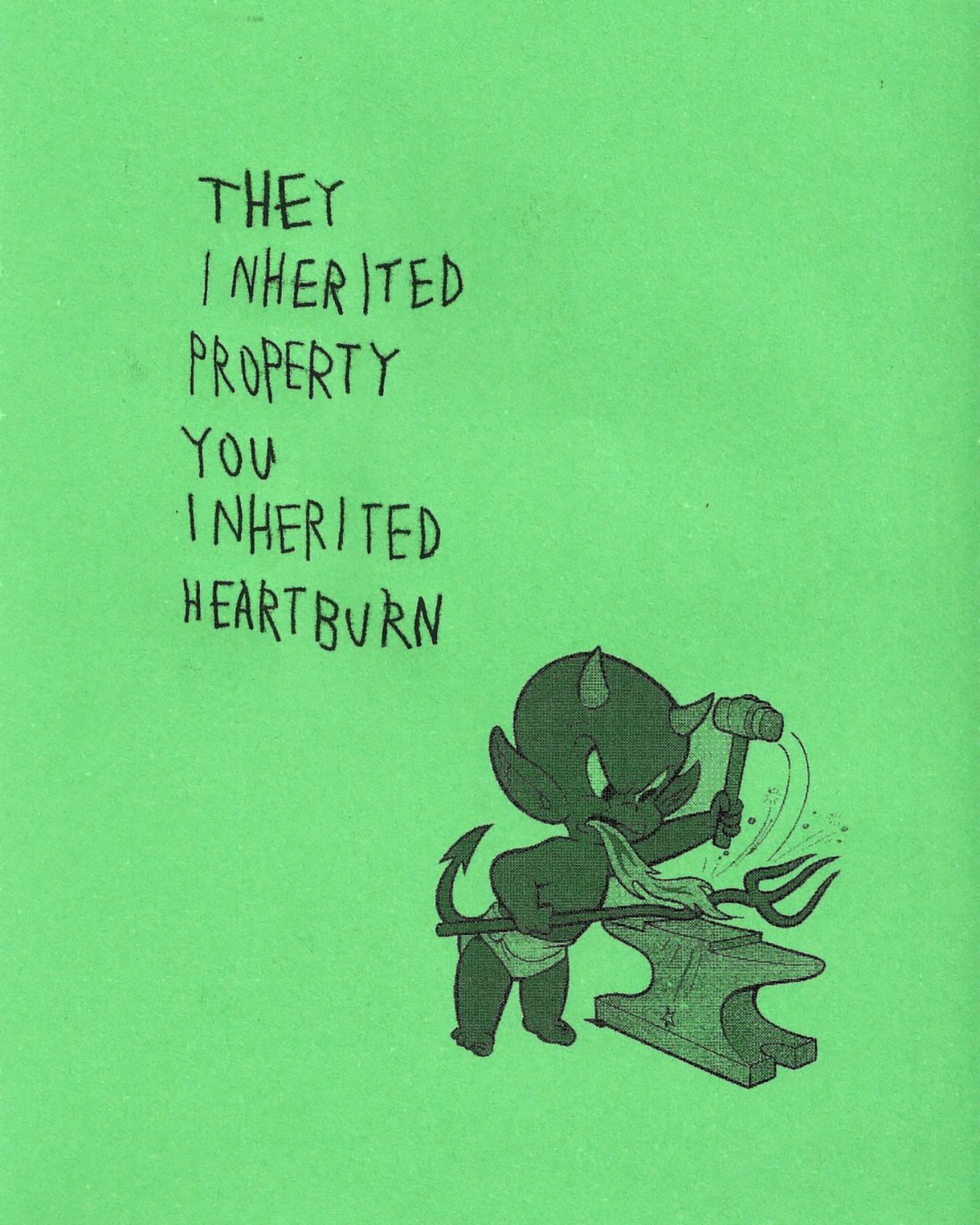

Your work is shaped by Scottishness, queerness, and class — not in isolation, but all at once. How do those identities inform one another in your practice, and how important is it for artists to embrace intersectionality?

I’m just speaking from lived experience. I’m Scottish, I’m queer, and I’m working class. It’s not something I consciously try to balance or layer in, it’s just who I am. So I don’t always think about those identities informing each other, because they’re already part of the same story. They’re just my background.

What I’m maybe more aware of is the idea that by showing my view of queerness, or class, or being Scottish, especially through humour and nostalgia – I might be introducing people to something they’ve not seen before.