Partnerships

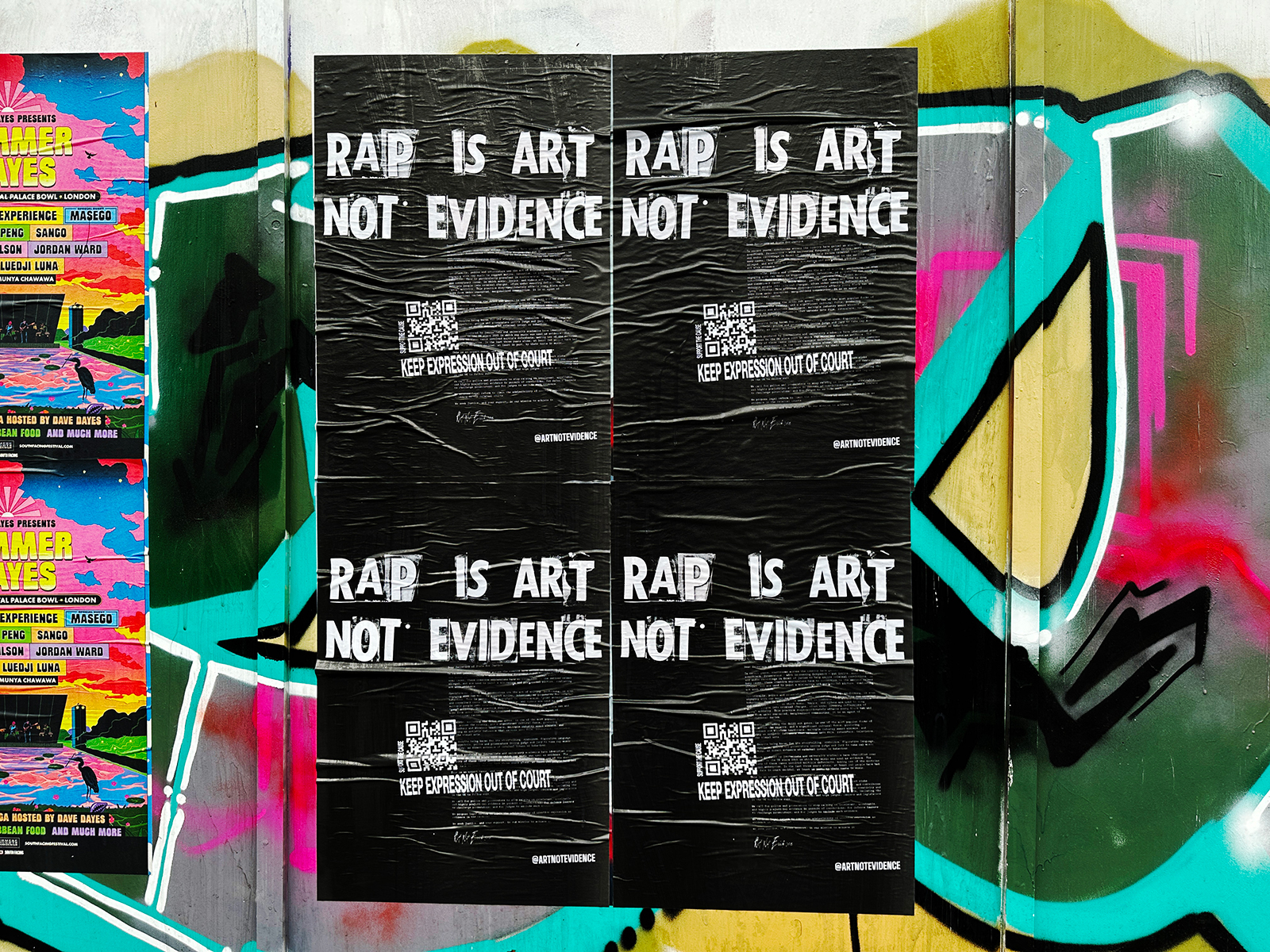

From the artistry of drill music, to the poetry of rap: Art Not Evidence is pulling the plug on creative injustice

From Digga D to Unknown T, artists and genres of Black origin have been painted with a murky brush of criminality well before the heady days of hip hop. With drill music well and truly established in the underground scene as well as hitting high in the mainstream charts, we chat with Art Not Evidence founder Elli Brazzill on the sorry state of musico-political affairs, and what Art Not Evidence plans to do to stop lyrics and creative expression being unjustly used as evidence in courts across the country.

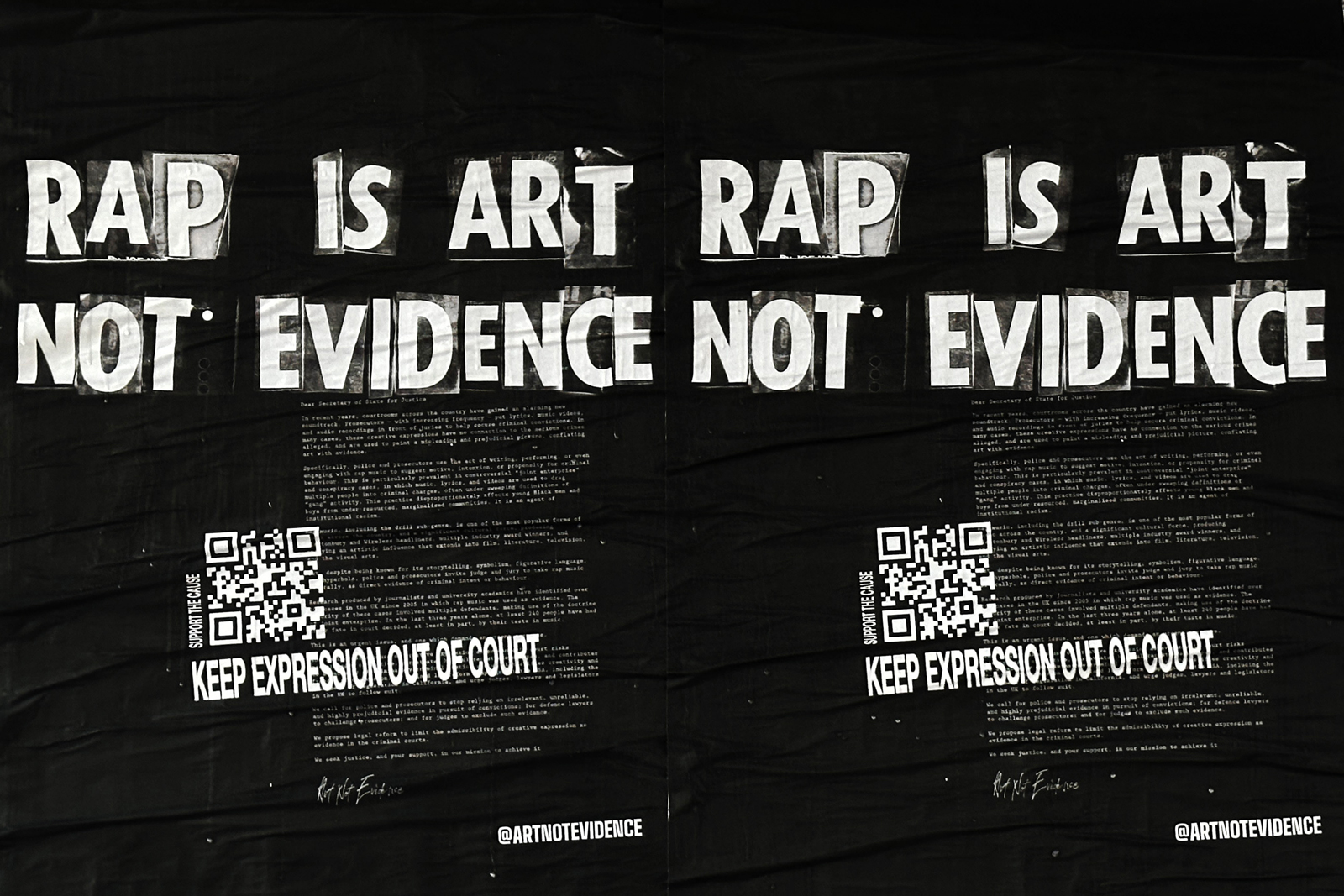

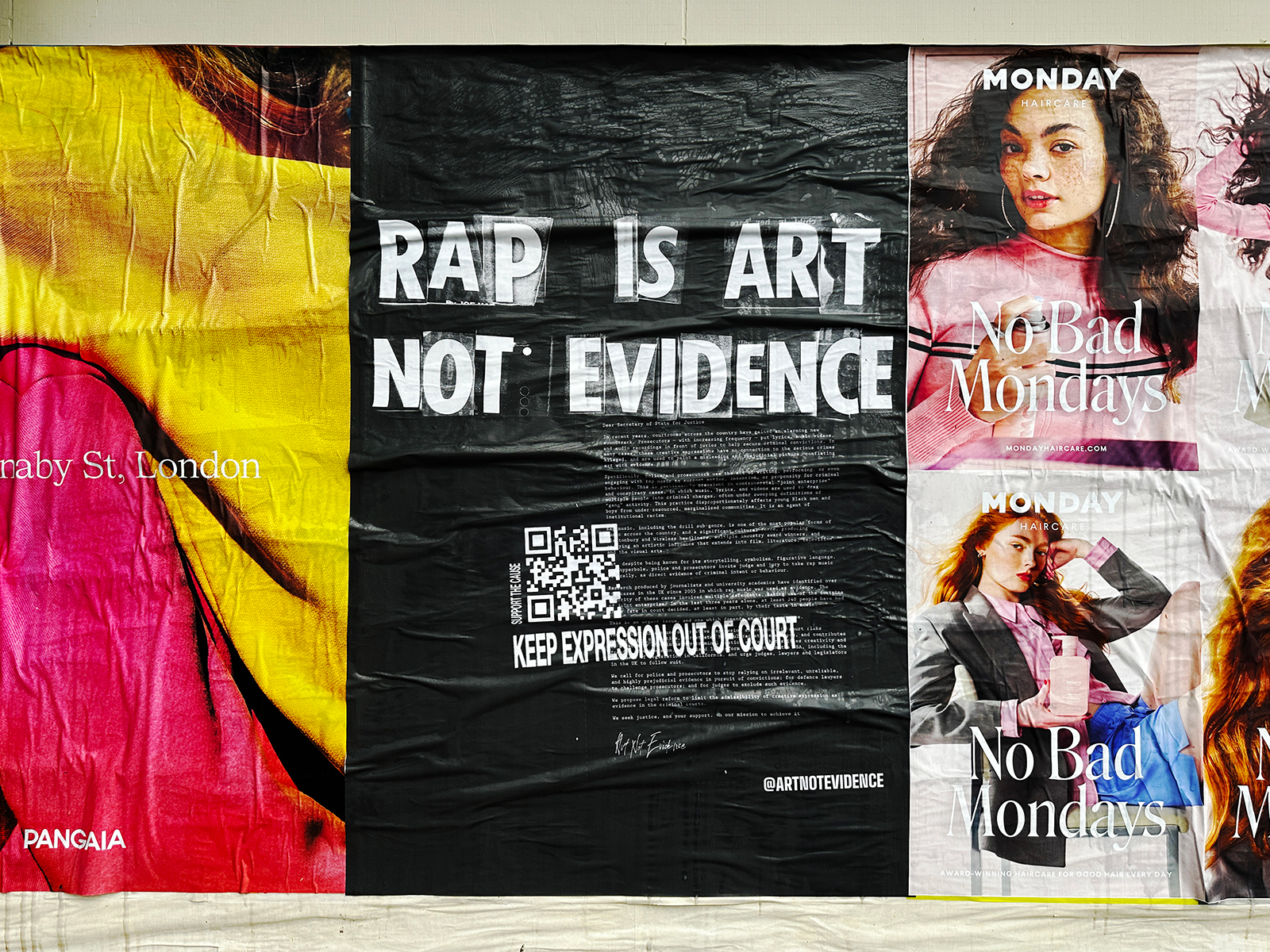

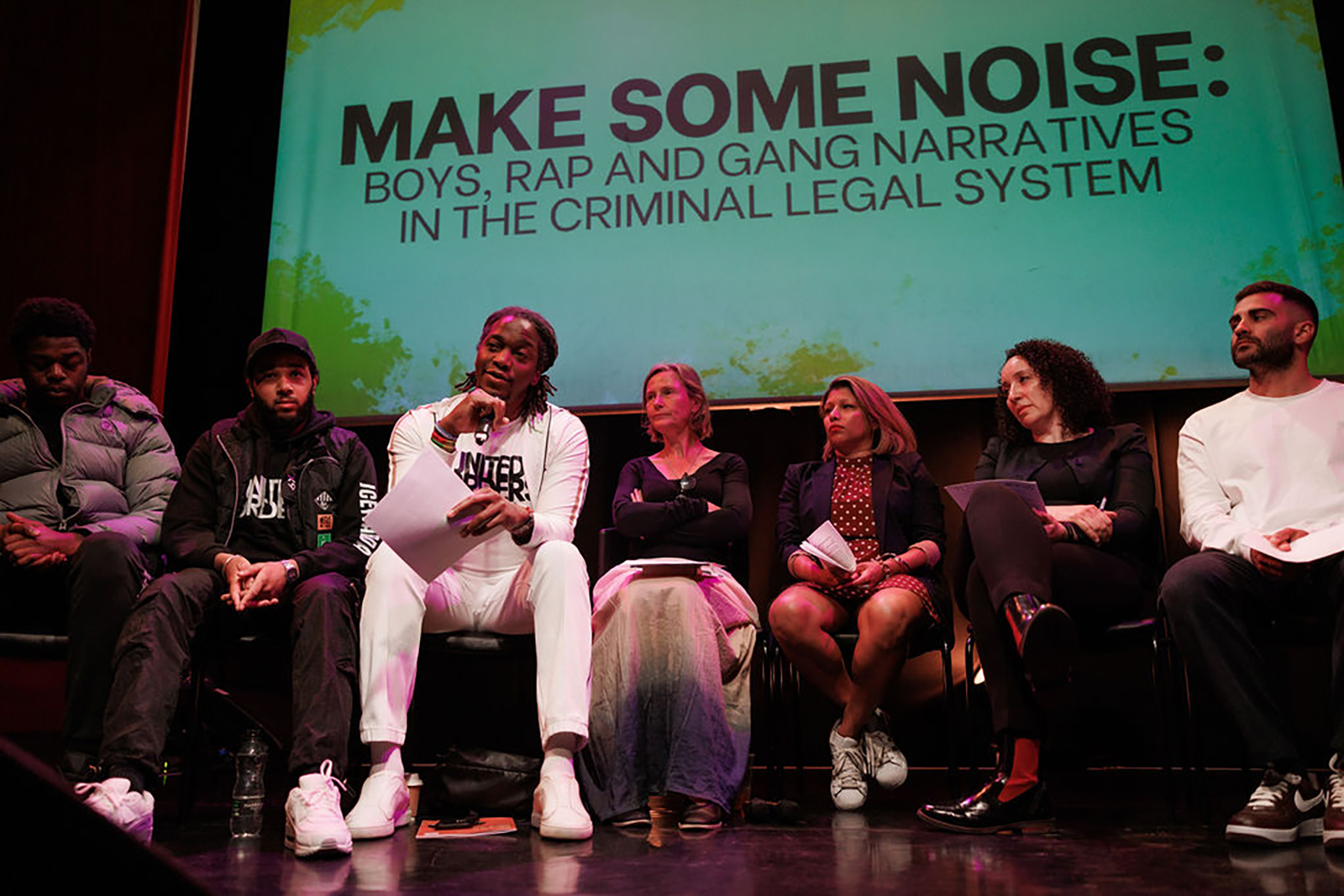

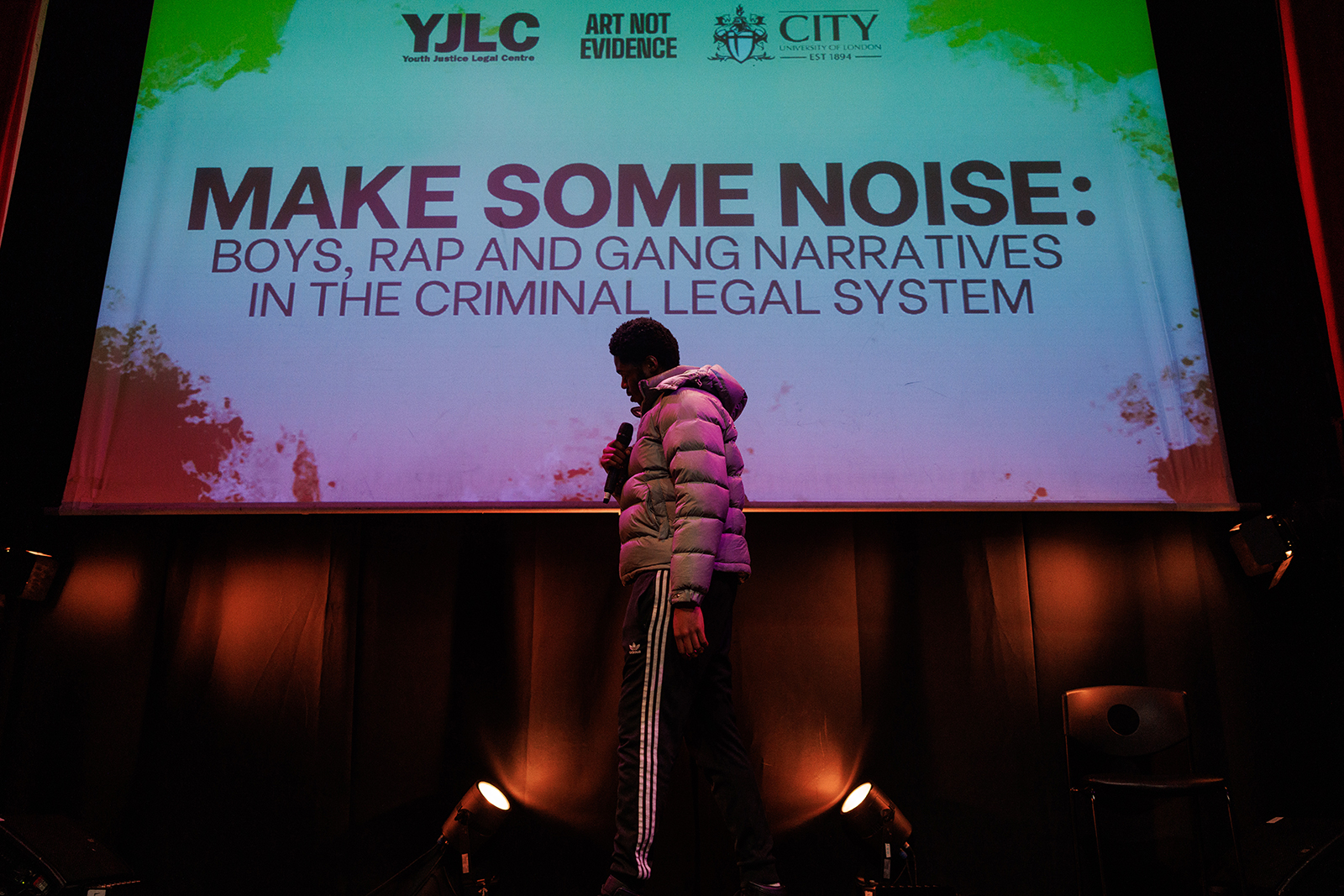

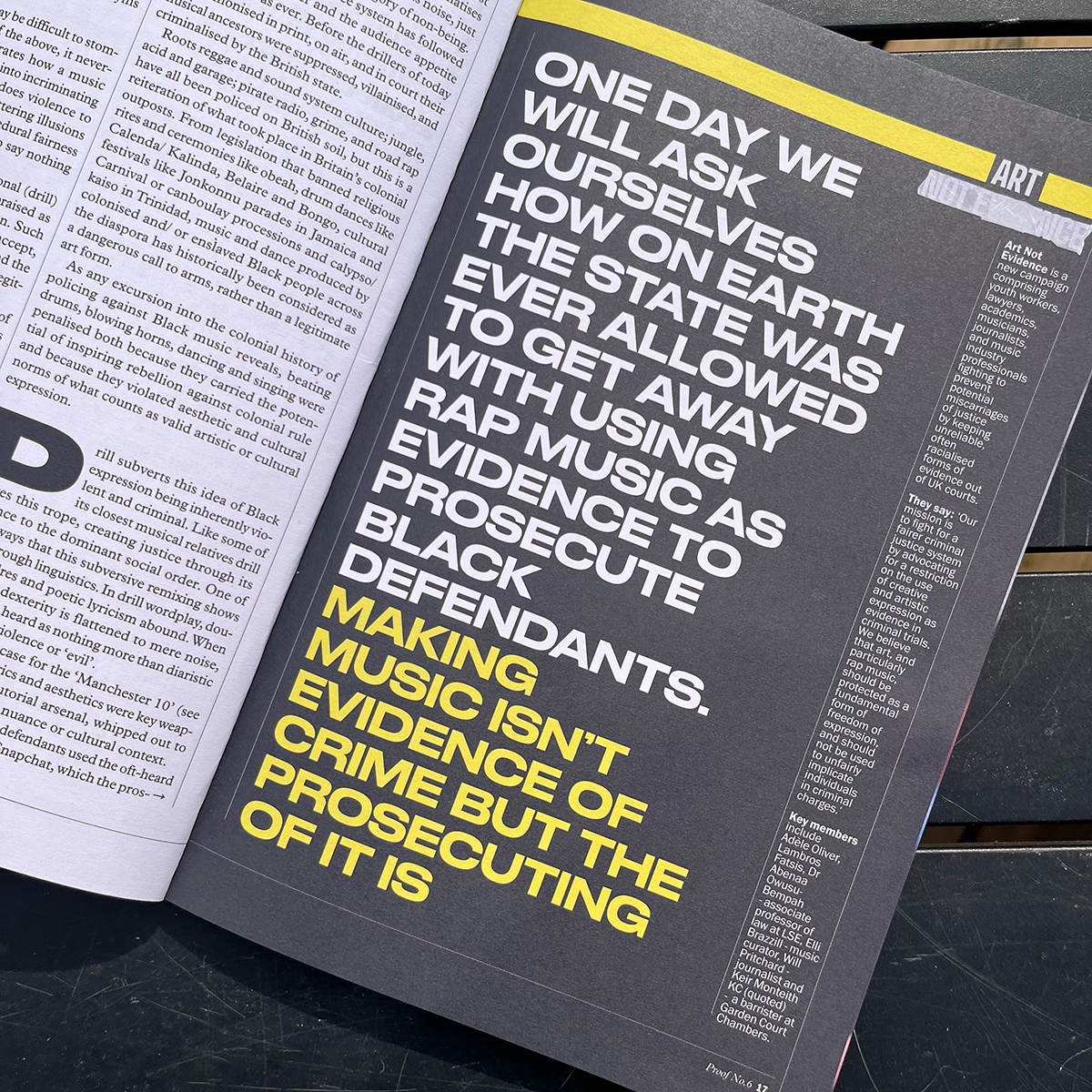

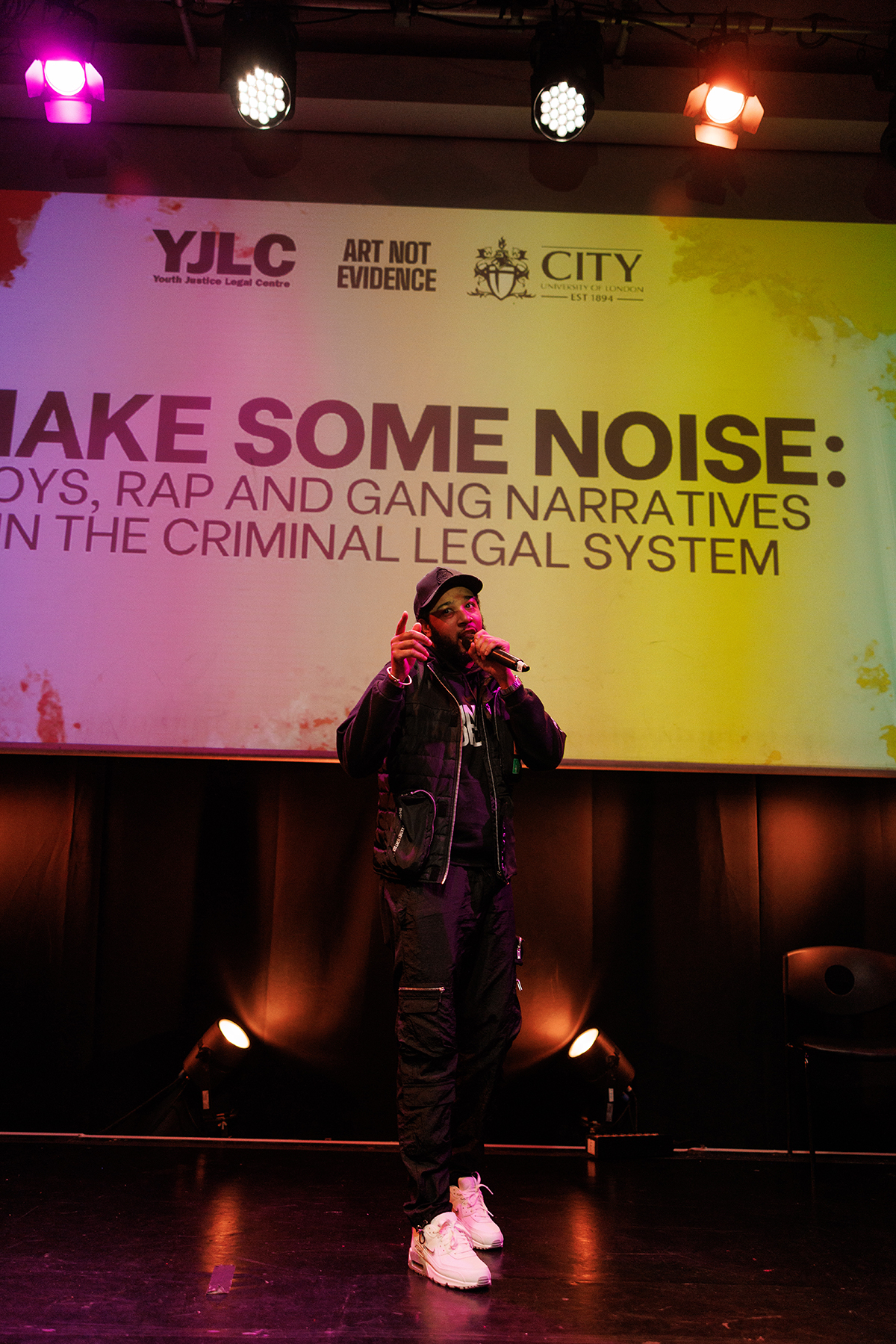

Art Not Evidence is a movement working hard to redress the use of lyrics as evidence that lead to miscarriages of justice, a non-profit organisation led by a broad coalition of youth workers, academics, lawyers, journalists, musicians, and music industry professionals holding the courts, police, and prosecution to account. The prejudice and racist assimilation of rap lyrics and music videos speaks to a grossly misinformed assumption that artists are more likely to be related to criminal “gang” behaviour, an insidious trope that has made its way through the courts of justice for years, long before the advent of drill, as a historical and deep-rooted discrimination against music of Black origin.

17.07.24

Words by