Partnerships

From billboard to ballot: Fashion’s first whistleblower is asking you to vote

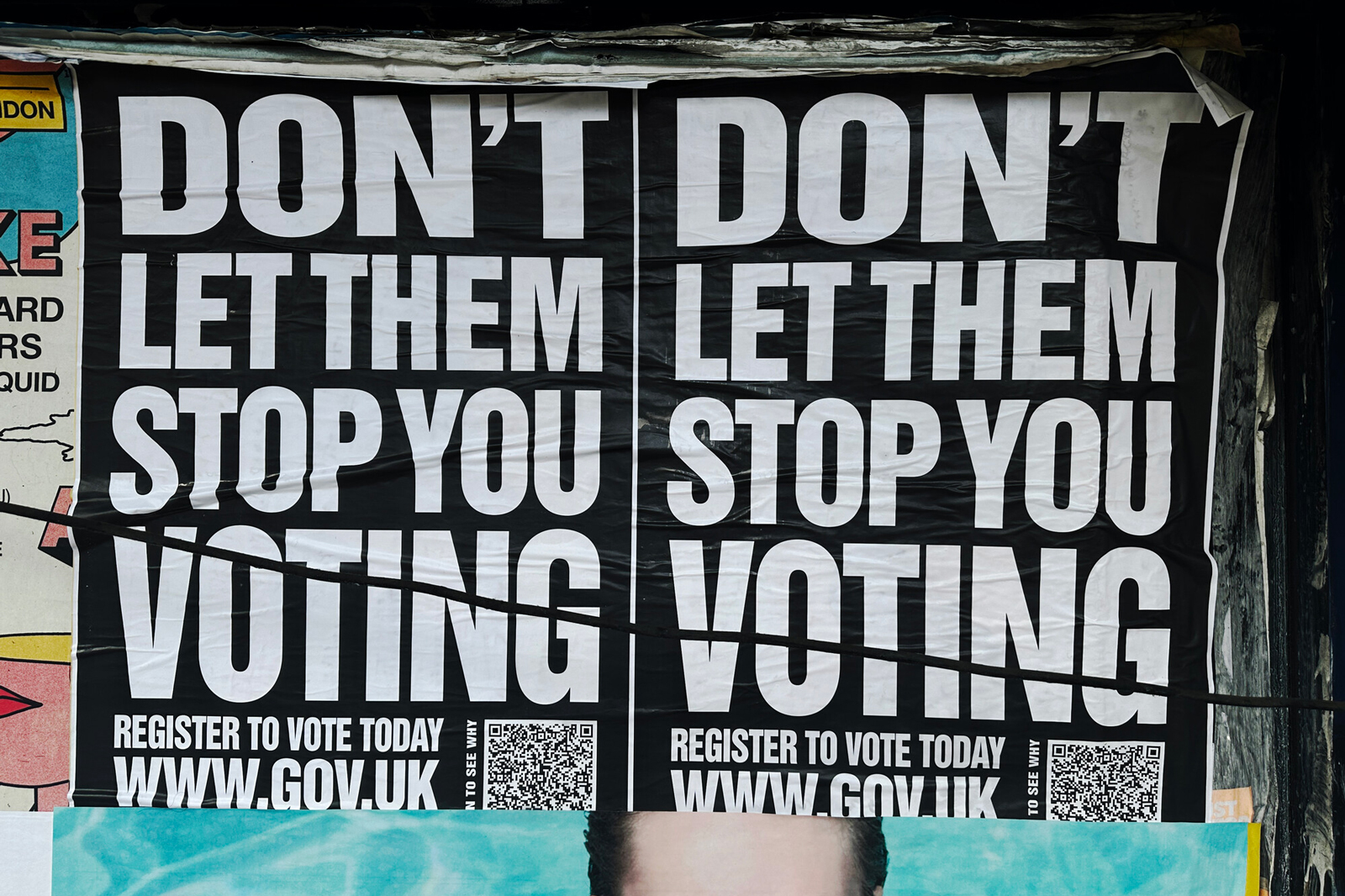

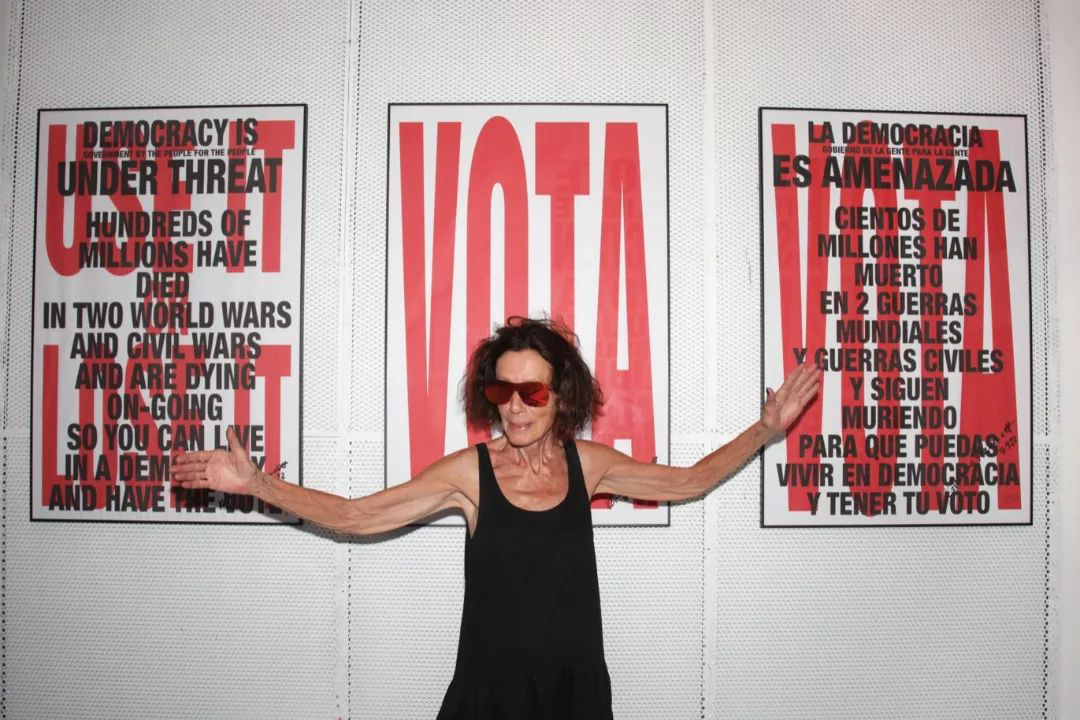

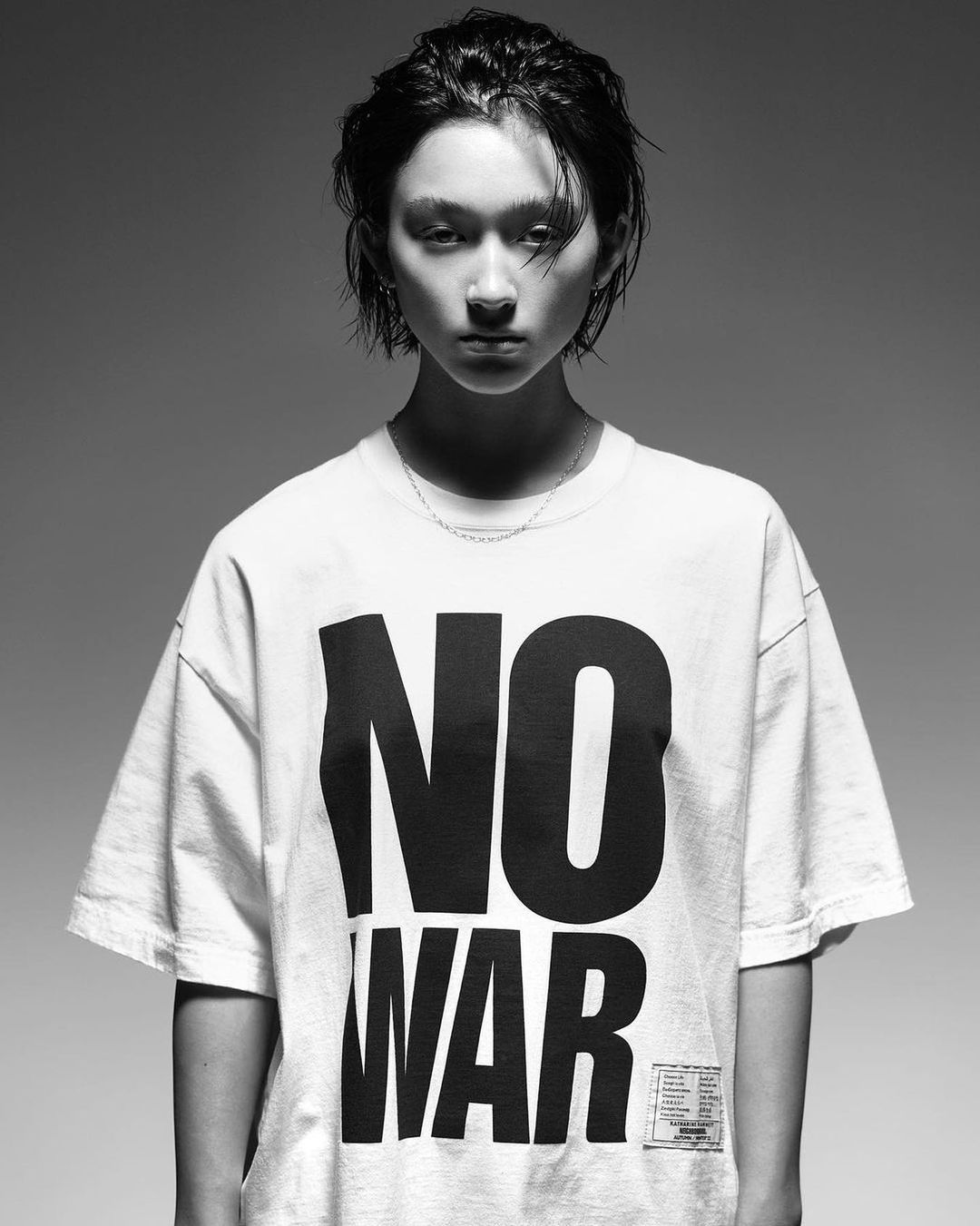

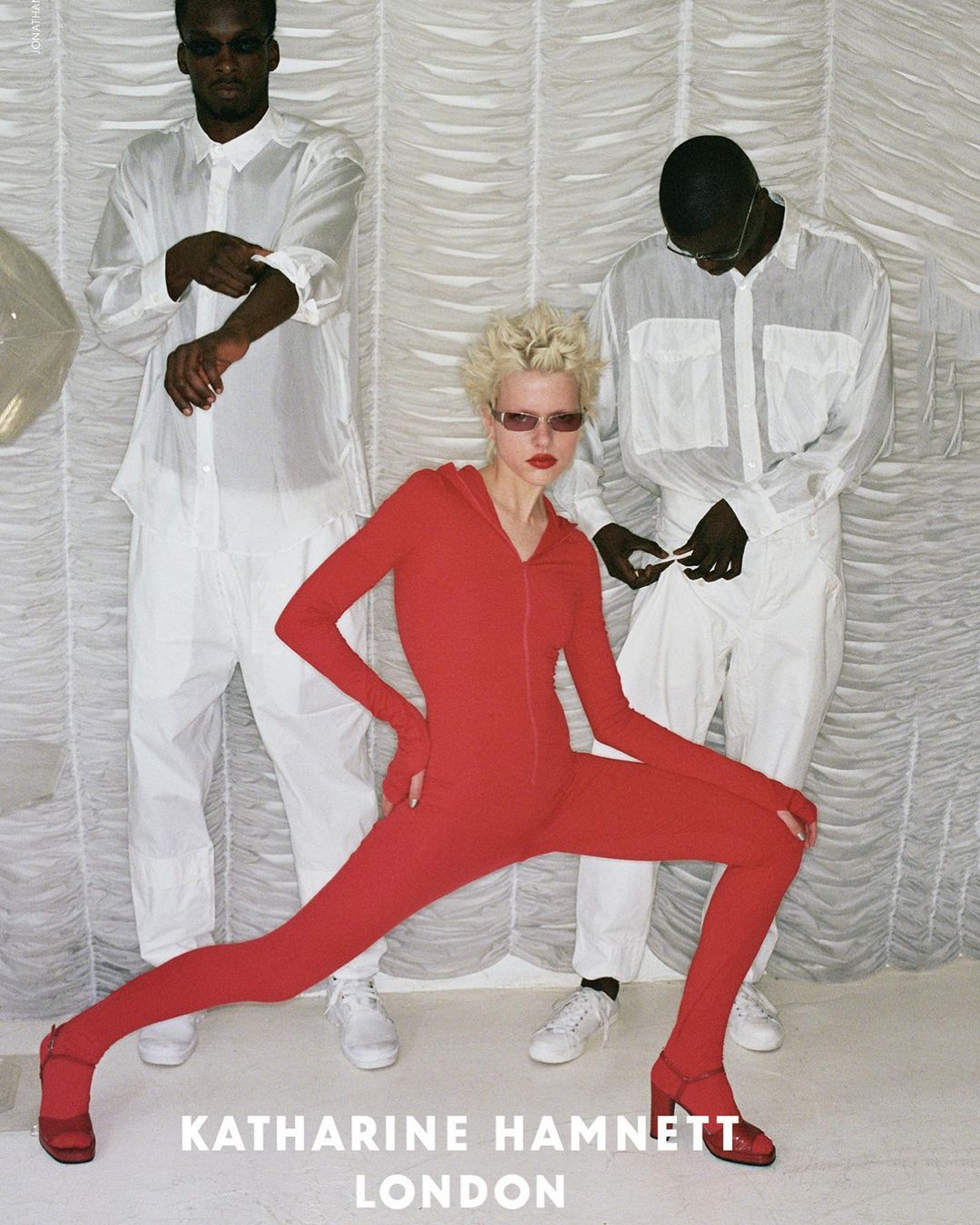

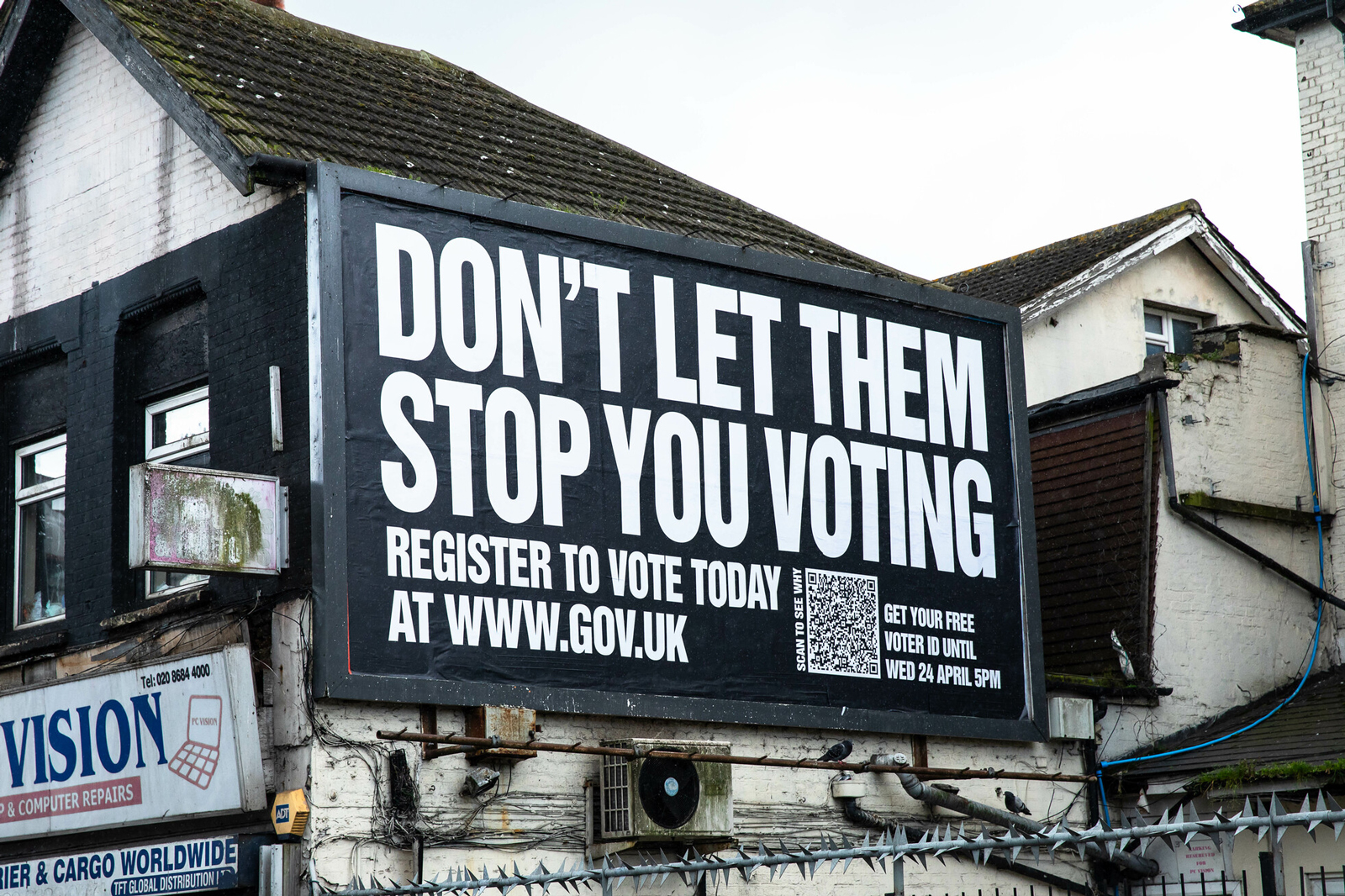

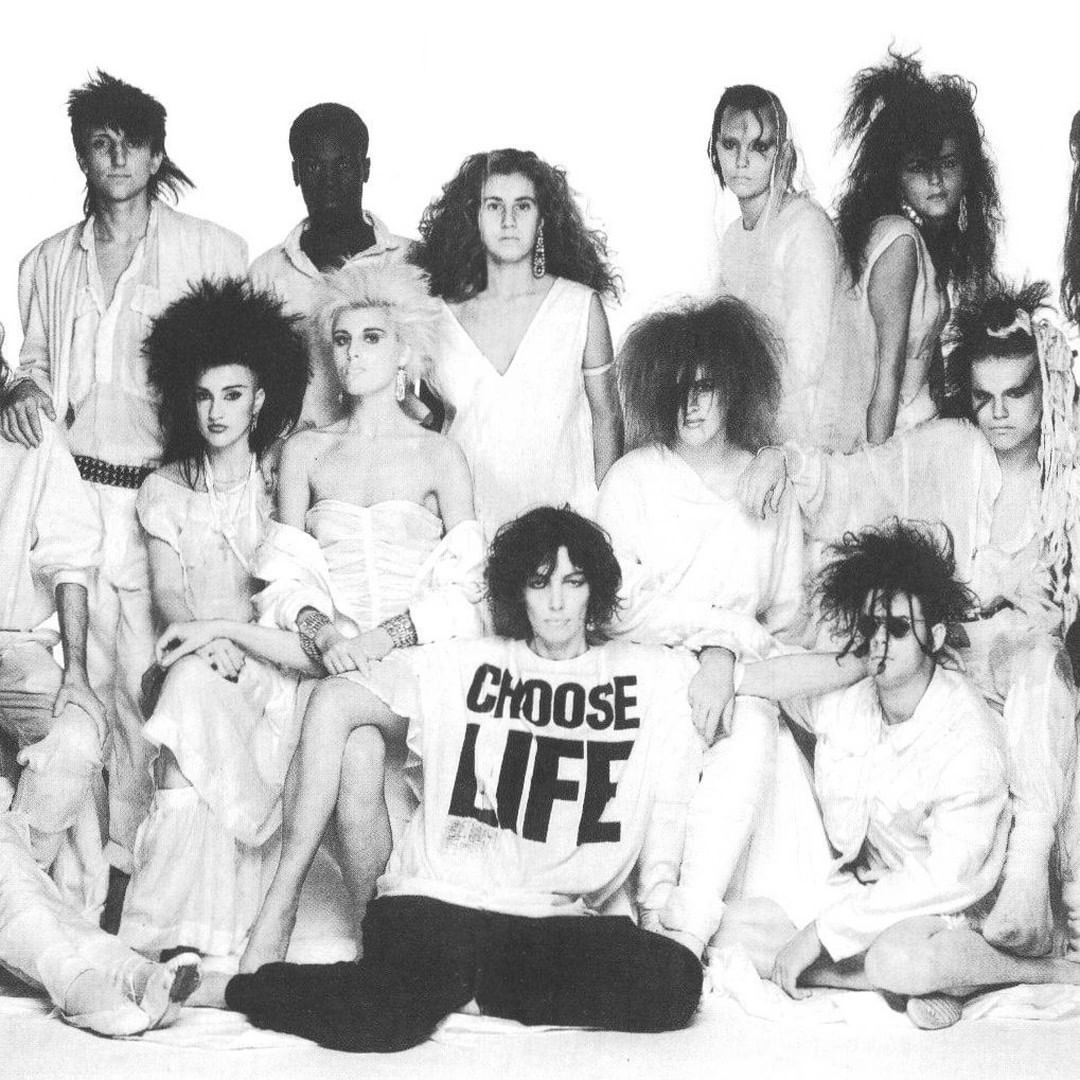

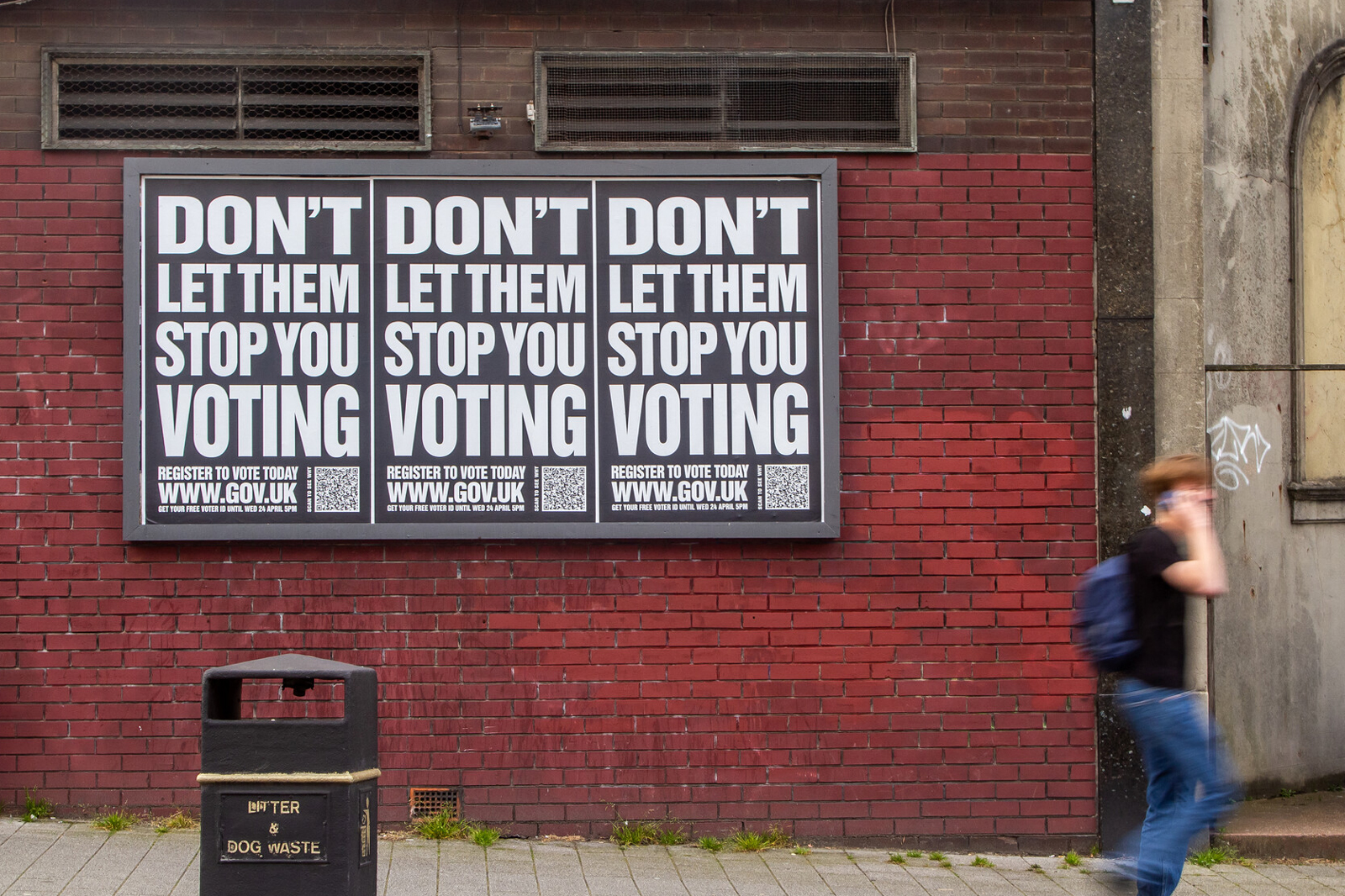

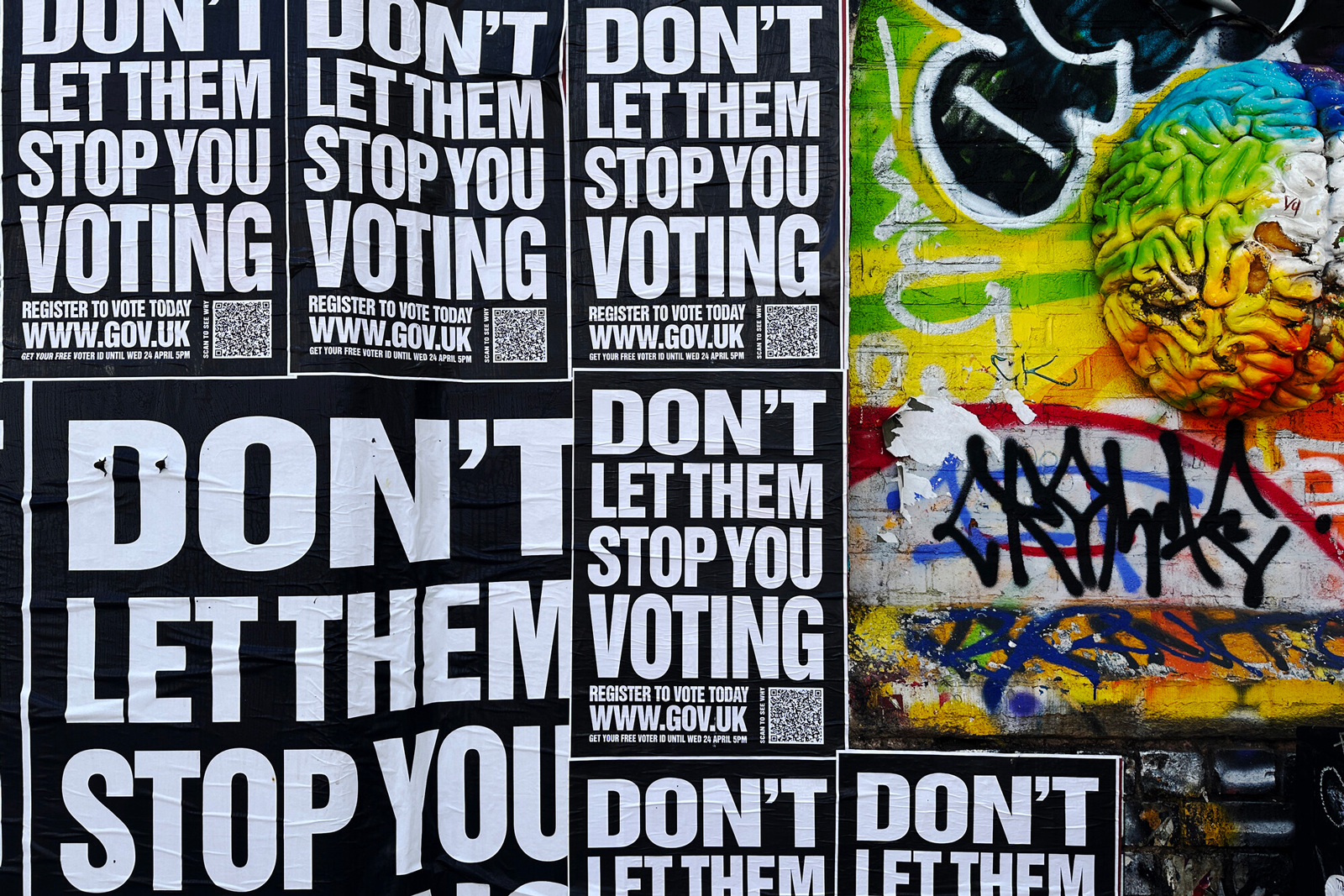

World renowned for her political T-shirt designs and planet-led activism, fashion’s first whistleblower Katharine Hamnett has taken to billboards with BUILDHOLLYWOOD to further spread her message. Cast your vote wisely.

With Arthur the dog sitting just out of shot beside her, Katharine Hamnett appears as if out of nowhere on the screen, captured in a bright room with a lit cigarette in one hand, periodically shifting in position to accommodate the sleeping hound to her left. “He has a dog pass, you see”, she shares, “so he can come everywhere with me, even to the Tate”. This kind of loyal company feels reminiscent of Katharine’s unwavering commitment to justice, her dogged determination for seeing things through properly, and her persistent hounding of political heavyweights to listen to the people, and to act accordingly.

It’s clear to all that Katharine Hamnett has a remarkable number of accolades to her name; from winning the first ever British Fashion Awards to renouncing her CBE on account of the Palestine crisis, her accomplishments appear to align wholeheartedly with her strong moral compass. A recent post on her instagram shows Katharine dressed in a black T-shirt with the words “DISGUSTED TO BE BRITISH” proudly emblazoned on the front, capturing her speaking a few words to camera before swiftly binning her CBE. “I’m not the only one disgusted to be British, apparently”, she comments when we discuss it in our interview. “We sold a tonne of those T-shirts”.

02.05.24

Words by