Partnerships

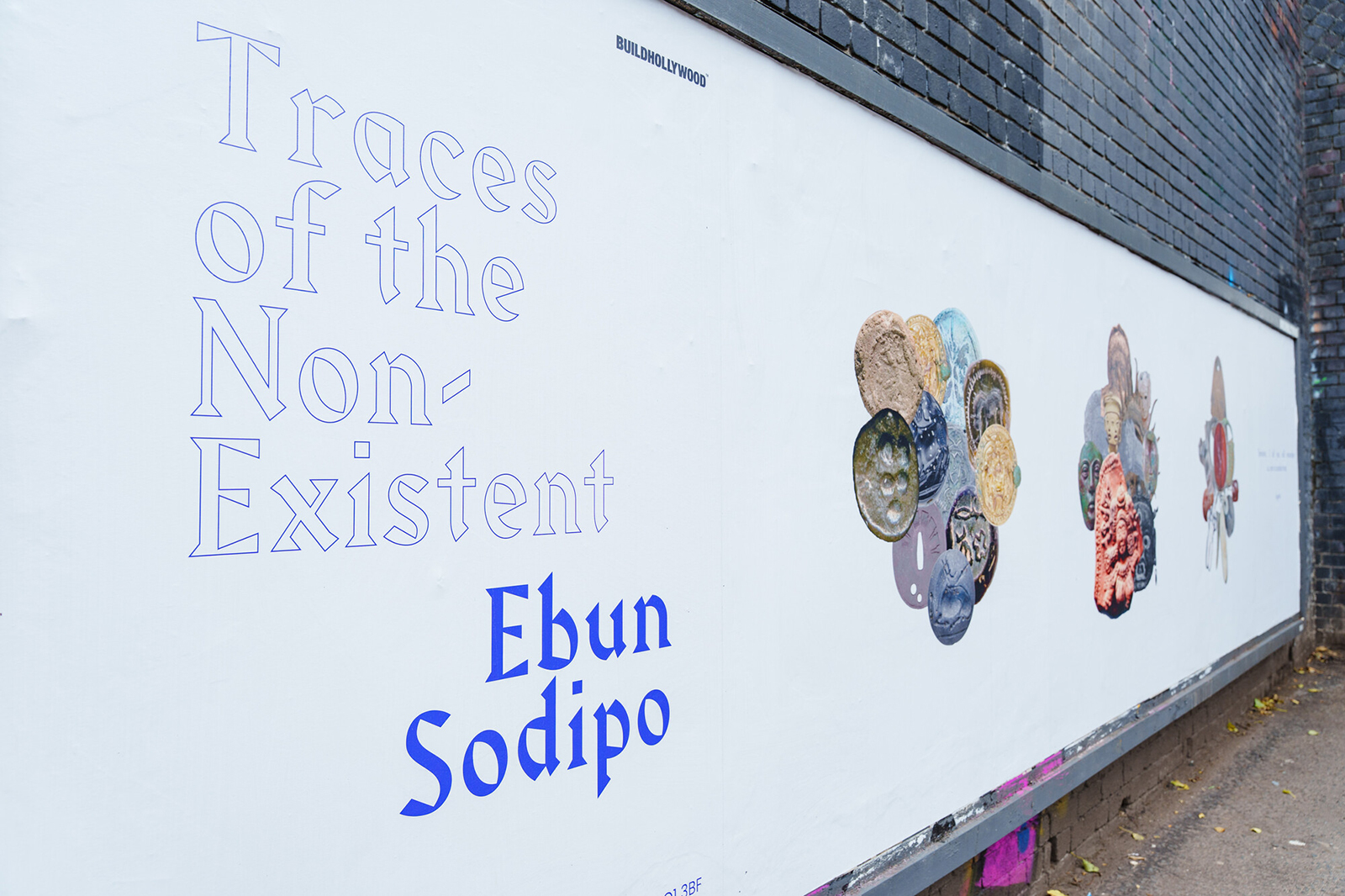

Ebun Sodipo is building a world for those that come after

Ebun Sodipo is an artist born of the internet; an astute, discerning, and deeply original practitioner folding time and stretching geographies to find belonging beyond the bounds of the Western art world. Responding to the concept of Pride with her latest billboard series, Sodipo speaks with BUILDHOLLYWOOD about trans futures, Atlantic Blackness, and the digital architecture of the beloved Tumblr archive.

Moving fluidly across text, performance, installation, and image, Sodipo is a multidisciplinary force whose work interrogates and reimagines Blackness, transness, and diasporic identity. Her practice is richly layered, often drawing from archives both digital and personal, while remaining focused on what might come next for future generations. Having been shown, read, watched, and performed across countless galleries, institutions, and centres of excellence across the globe, Sodipo’s work has found a new home this summer in the UK, this time on city streets, marking a public illustration of what Pride represents in principle and practice for Sodipo and the communities she feels at home in.

Born in London and raised in Nigeria until the age of eleven, Sodipo’s sense of identity has long been shaped by migration, multiplicity, and the navigation of cultural space. More than physical place, it was the internet that served as her earliest landscape of creative re-imagining. “I was a Tumblr girly”, Sodipo laughs, “so I access a lot of archival material through the internet”. In this way, a ubiquitous household object, the flickering Wi-Fi router, becomes a kind of commonality, one that connects her to a broader constellation of Black life and thought. That little plastic box that acted as the director of many of our early millennial and Gen Z childhood antics remains a steadfast reminder of the vast chasm of knowledge we have at our fingertips; “I’m thinking about how we access history nowadays”, shares Sodipo. “I hold like 10,000 years on my computer, you know?”

24.07.25

Words by

Photo: Matteo-Strocchia

Photo: Matteo-Strocchia

Photo: Eva Herzog

Photo: Eva Herzog

Traces of the Non-Existent, Aspex Portsmouth (2025). Photo: Chantale Goble

Traces of the Non-Existent, Aspex Portsmouth (2025). Photo: Chantale Goble

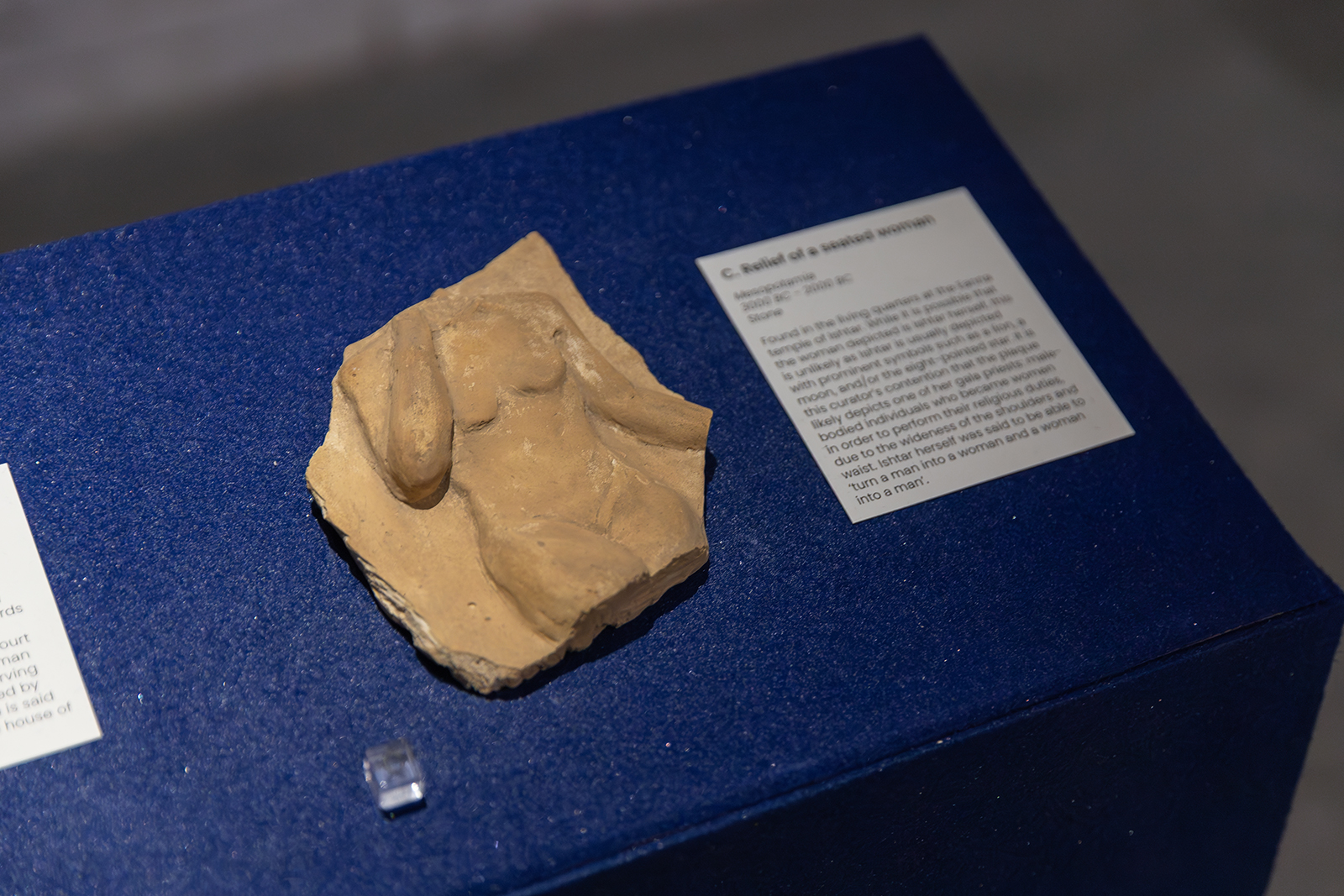

Traces of the Non-Existent, Aspex Portsmouth (2025). Photo: Chantale Goble

Traces of the Non-Existent, Aspex Portsmouth (2025). Photo: Chantale Goble

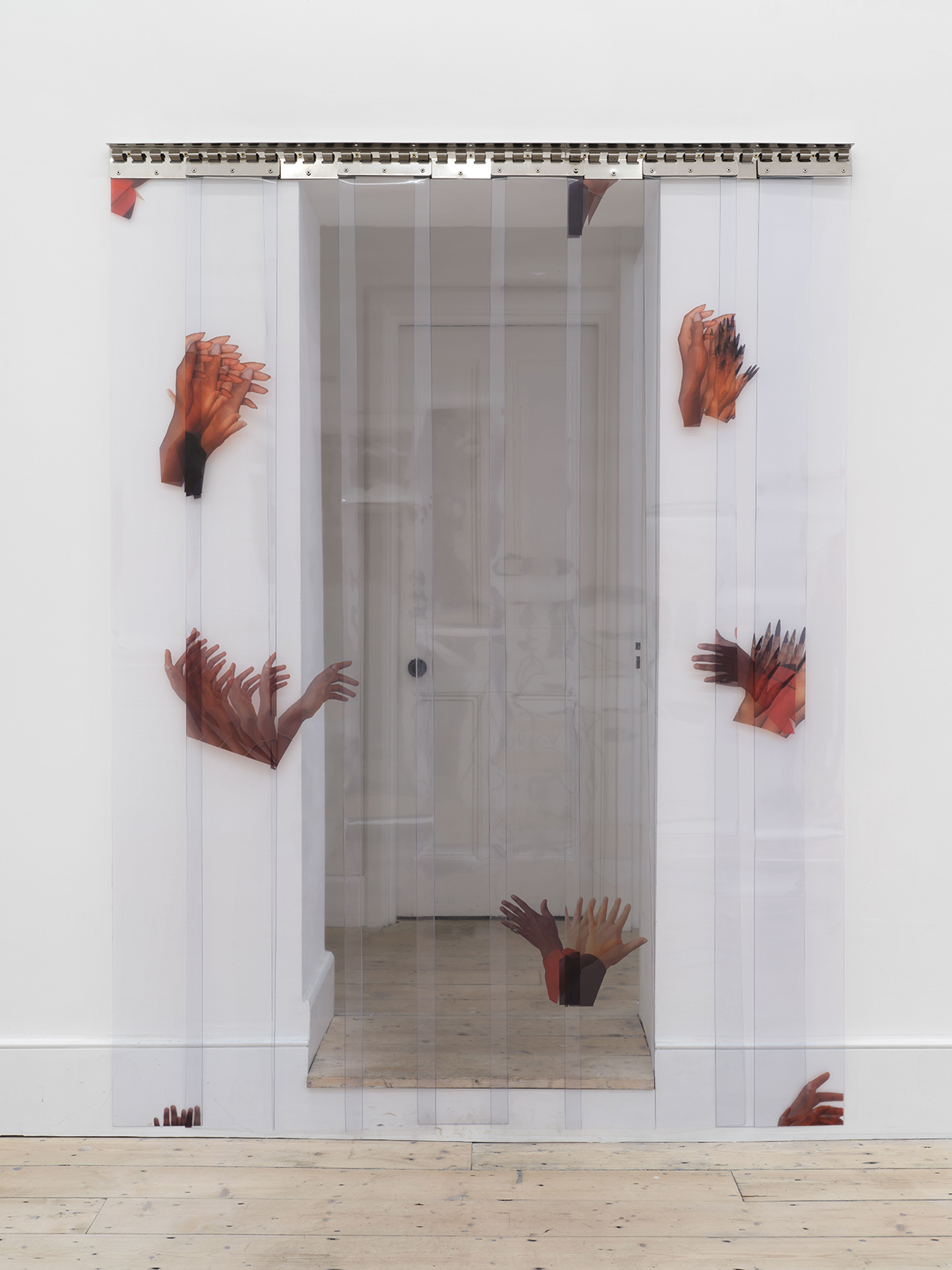

Traces of the Non-Existent, Aspex Portsmouth (2025). Photo: Karl Bailey

Traces of the Non-Existent, Aspex Portsmouth (2025). Photo: Karl Bailey

Traces of the Non-Existent, Aspex Portsmouth (2025). Photo: Karl Bailey

Traces of the Non-Existent, Aspex Portsmouth (2025). Photo: Karl Bailey

Traces of the Non-Existent, Aspex Portsmouth (2025). Photo: Karl Bailey

Traces of the Non-Existent, Aspex Portsmouth (2025). Photo: Karl Bailey

Photo: Rita Silva

Photo: Rita Silva

Photo: Eva Herzog

Photo: Eva Herzog

Traces of the Non-Existent, Aspex Portsmouth (2025). Photo: Chantale Goble

Traces of the Non-Existent, Aspex Portsmouth (2025). Photo: Chantale Goble