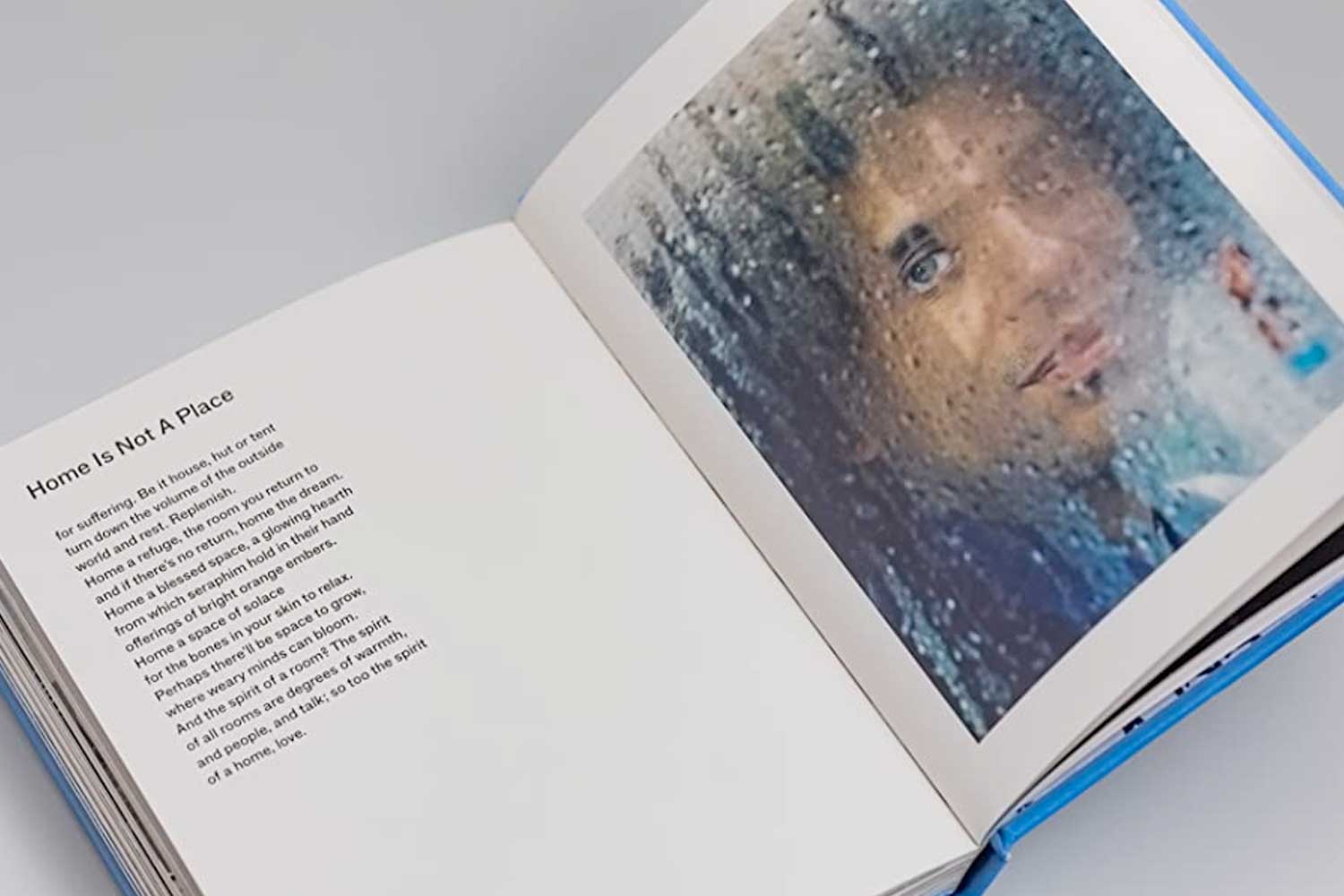

Immediately, from the first poems and photographs, key themes are broached. ‘Hiss’ quietly despairs at the low-level static of racism experienced when Black people rock up at seaside resorts: sites deemed by some too far removed from stereotypical inner-city habitats.

After the concise form and staccato rhymes of the opening text comes a meditation on ‘The Quality of Light’ in art and writing. There’s the remembered lux we carry with us. And then there’s the affect of the light we live with day to day. Different types of light are attendant on different locales and times of the year. And, when dealing with such a mercurial medium, ‘Maybe it’s about who / you’re writing for and what you’re reading, / where you’ve lived and where you’ve been / and what light does to the skin you’re in.’

Following that rippling, luminous rumination on light is stark horror. Robinson’s ‘Taxidermy’ recounts in measured quatrains, the lot of a female slave who was ‘so beloved’ by her slaver that after death he had her hand taxidermied as a family heirloom and thus ‘[…] her hand remained a slave in a way / it remained captured in service against her will’.

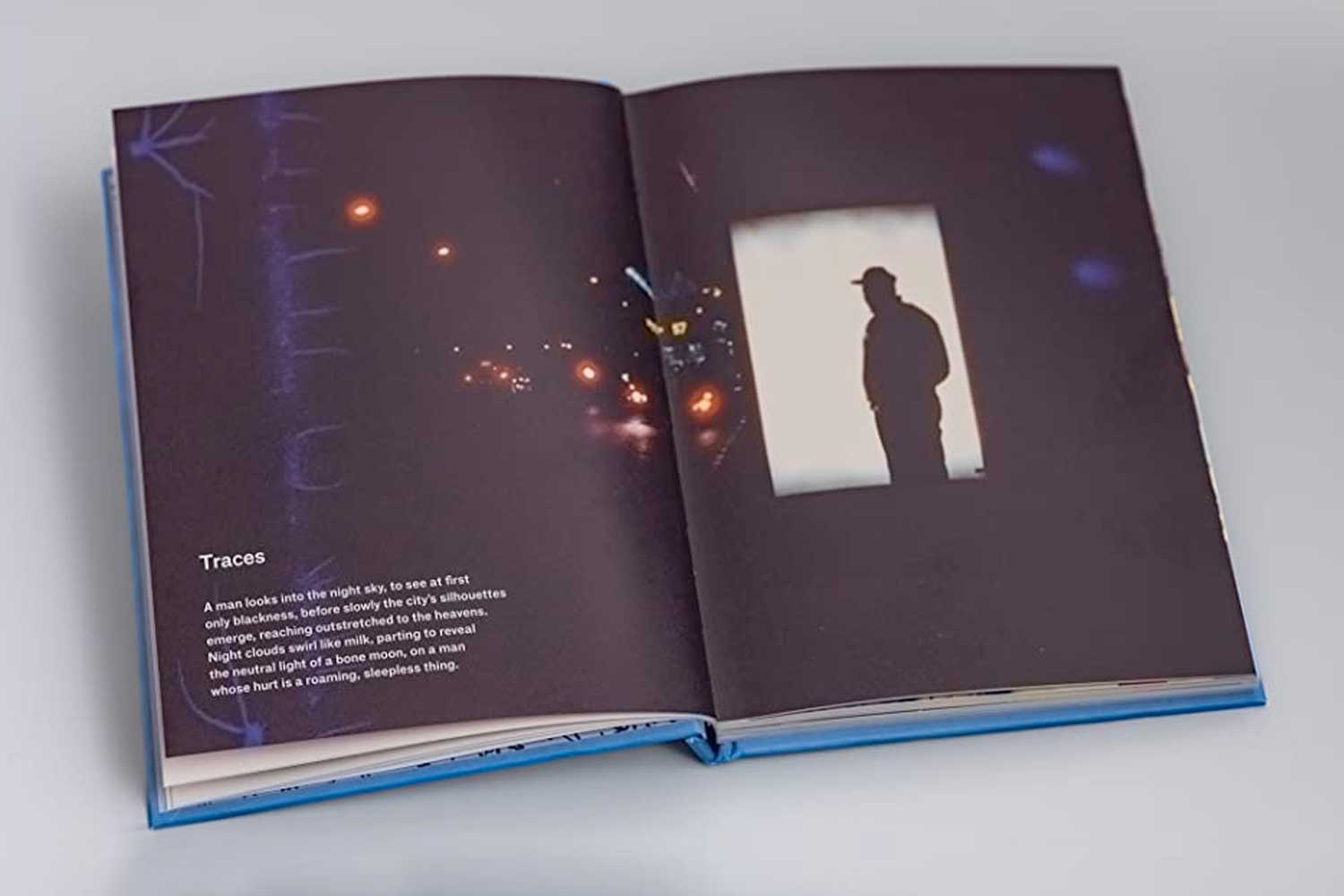

‘Traces’ couples the emerging imagery of a night sky with a man ‘whose hurt is a roaming, sleepless thing’. ‘Guy Fawkes Night’ likens helping a child overcome their fear of fireworks to a father’s calling to help them ‘past their crying to view dark skies with awe.’

So, after just a handful of poems we know we’re in for a harrowing read. Considering Robinson’s texts there’s illumination, yes, though the achingly painful hurt intertwined with Black experience is fast stacking up. Then, of course, paired with texts and in short series between the words we are treated to Pitt’s photography, his multivalent gaze.

Facing Robinson’s ‘Hiss’ is Pitts’ portrait of black guy giving his cloudlike afro free rein. So much so, his hair comically obscures nine tenths of a car in the near background of the picture. It’s a ludic capture, a moment of freedom, an everyday celebration, and a celebration of the everyday.

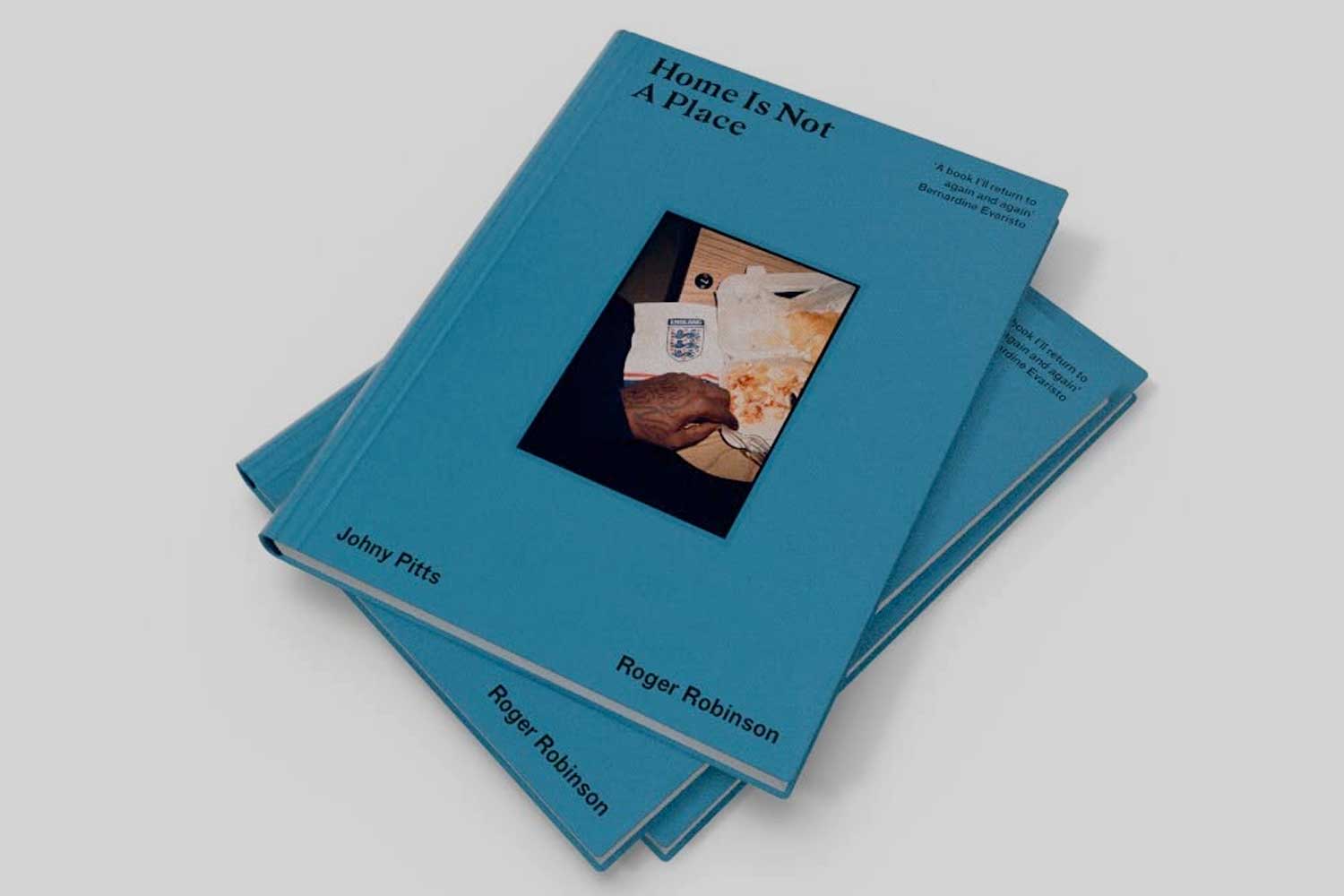

Pitts’ photographs don’t illustrate Robinson’s words. Rather they are counterpart or complimentary to the texts. There’s sequences of adhoc street photography, then we go from the gorgeous brilliance of a smiling portrait to more enigmatic framing. A close-up of a black hand tattooed with a Copperplate text resting his plastic fork at the edge of the dregs of a fish and chip supper in a polystyrene hinged lid box. We know it’s a café or cheap restaurant as there’s a number 7 tag screwed to the table. There’s also a tea towel or serviette bearing the Three Lions FA crest badge. The pared down elements in this picture conjure drama and food for thought aplenty. (In fact, Pitts revealed in a recent newspaper article that the hand in this photograph belongs to Robinson and the tattooed names are those of his wife and son.)

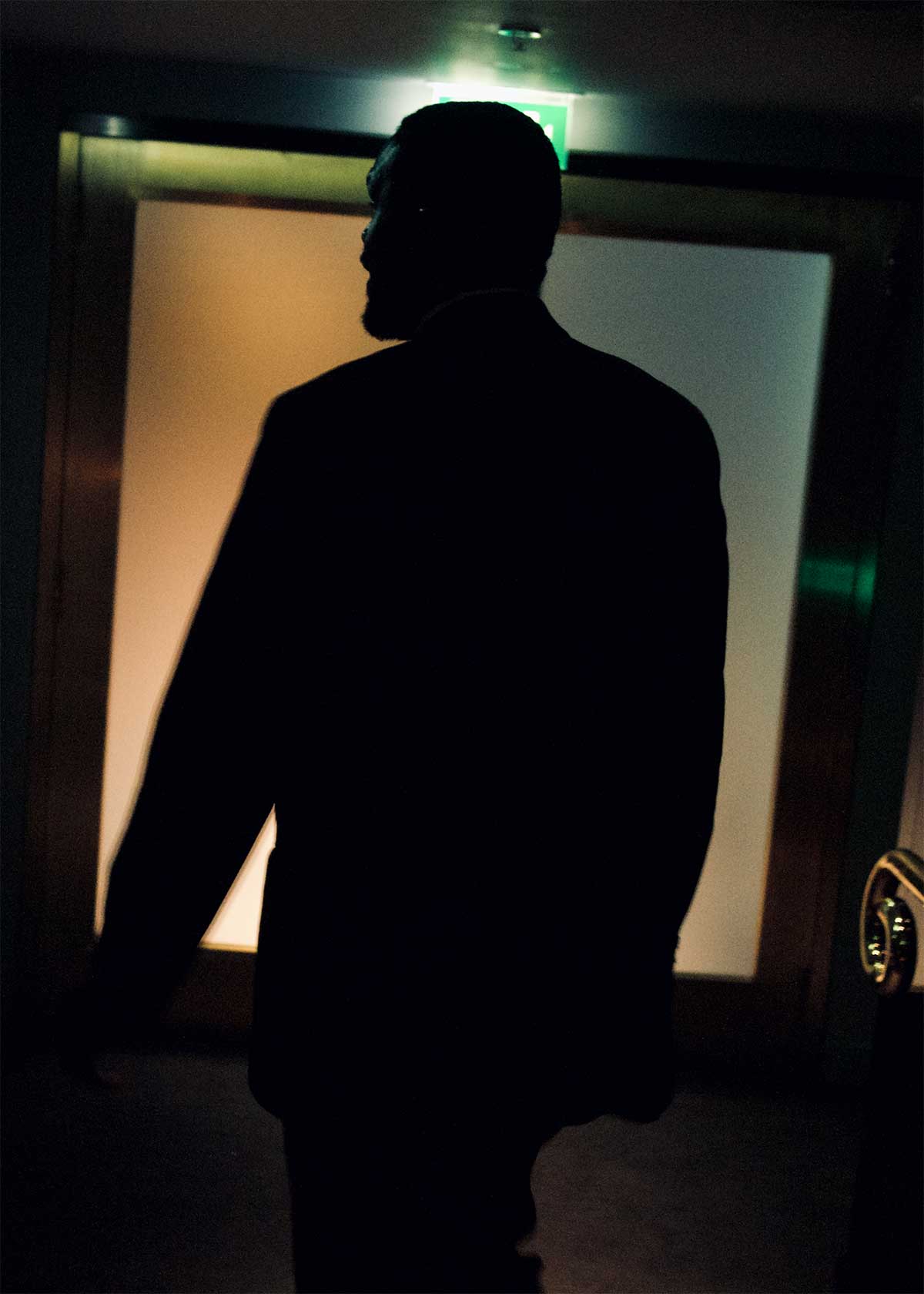

Opposite Robinsons’ ‘Taxidermy’ poem Pitts’ image is a gritty, almost abstract partial silhouette. The ghost of a figure wrought in the colour of dried blood, a phantom in texture and tone.

The poem ‘Traces’ is set within the dark environs of Pitts’ photograph. A lone figure standing against the cool white radiance of an empty backlit bus stop ad. Again, this image doesn’t literally reproduce what’s going on the poem, it offers an enhanced atmosphere to ponder the destiny of this man who looks into the night ‘to see at first / only blackness’.

I’m painting quite a bleak picture here. But there’s bright pride, hope and humour too in both text and imagery. ‘Twenty Parakeets’ (in a tree beside a Dover car park, wearing their ‘bright yellow anoraks’) conveys a childlike wonder and delight. And ‘The City Kids See the Sea’ affords a palpable glee.

There’s mystery too. Robinsons’ taut rebuke in the poem ‘Survivals’: ‘Don’t fall into dreams / of other men who don’t care / that you wake screaming.’ And there are series of Pitts’ photographs where we must read and reread the imagery to make out faces and forms in kaleidoscopic window reflections. Except kaleidoscopes are symmetrical, you might predict an outcome. There’s nothing predictable about turning the pages of Home Is Not A Place. How can there be? The reader is witnessing, sharing an act of discovery and recovery, recognition and exaltation. This journeying along with two invested, finely tuned chroniclers of lesser-known Black British experience fosters both dismay and vibrance.

Pitts’ photographs of the quotidian, where we observe daily events closely with fresh eyes, is matched by Robinson in a poem like ‘Deal’. There’s an economy of language, a plain speaking that equates with the town’s brutalist concrete pier. The poet shares prosaic details of walking along the sea front: ‘beach houses of the quirkiest colour / and shapes, which are mostly empty.’ And notes the town’s damned historical reputation: Deal’s had a bad rep. for centuries. There’s plain, mundane and kindly visitor-centre-type advice: ‘The wind is so blustery that it would be wise to take off your cap / because it will soon be lost.’ Bound up in the commonplace, seemingly part of the very fabric of the place, there’s a mild suspicion of strangers: ‘I am told it’s to be expected because only five Black men live / in Deal and perhaps they thought that I was to be the sixth.’ But Robinson concludes this informational, low-key musing with an account of how contemporary smugglers drop off their human cargo hundreds of metres from the shore and let them swim to dry land: ‘Daily, people wash up on the beach.’ In one understated text we’ve gone from Baedeker banality – ‘There are fish in these waters. There are fishermen in boats.’ – to the worst degree of human baseness.

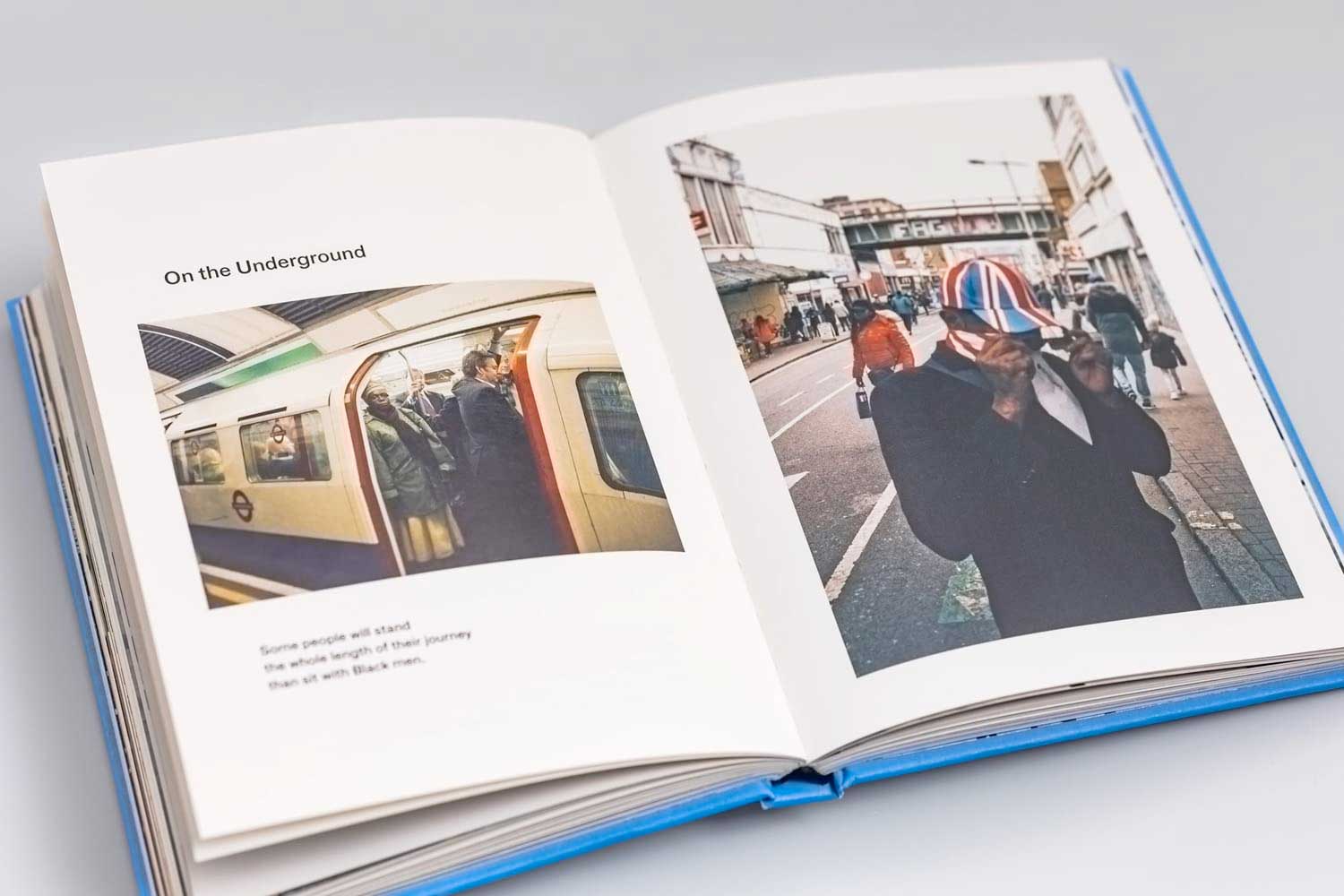

While the unvarnished tone of ‘Deal’ mean it works stealthily on the reader, the poem ‘Soundtrack’ is an incessant, driving beat of righteous insurrection: ‘From the bass and the drum / the snap and the snare / out of car windows and into the air / it’s the sound of Bristol / as they smash storefronts to crystals.’ On the page facing this rhythmic text is a photograph of a Black policeman, standing at the end of a train carriage, helmet clutched under one arm, his expression impassive, it’s the likes of him who had to: ‘Hear the marching boots / and the shouting youths / saying Kill the Bill / we’ll keep fighting till / you give us back our freedoms.’ Poem and picture between them again conjuring more than the sum of their parts.

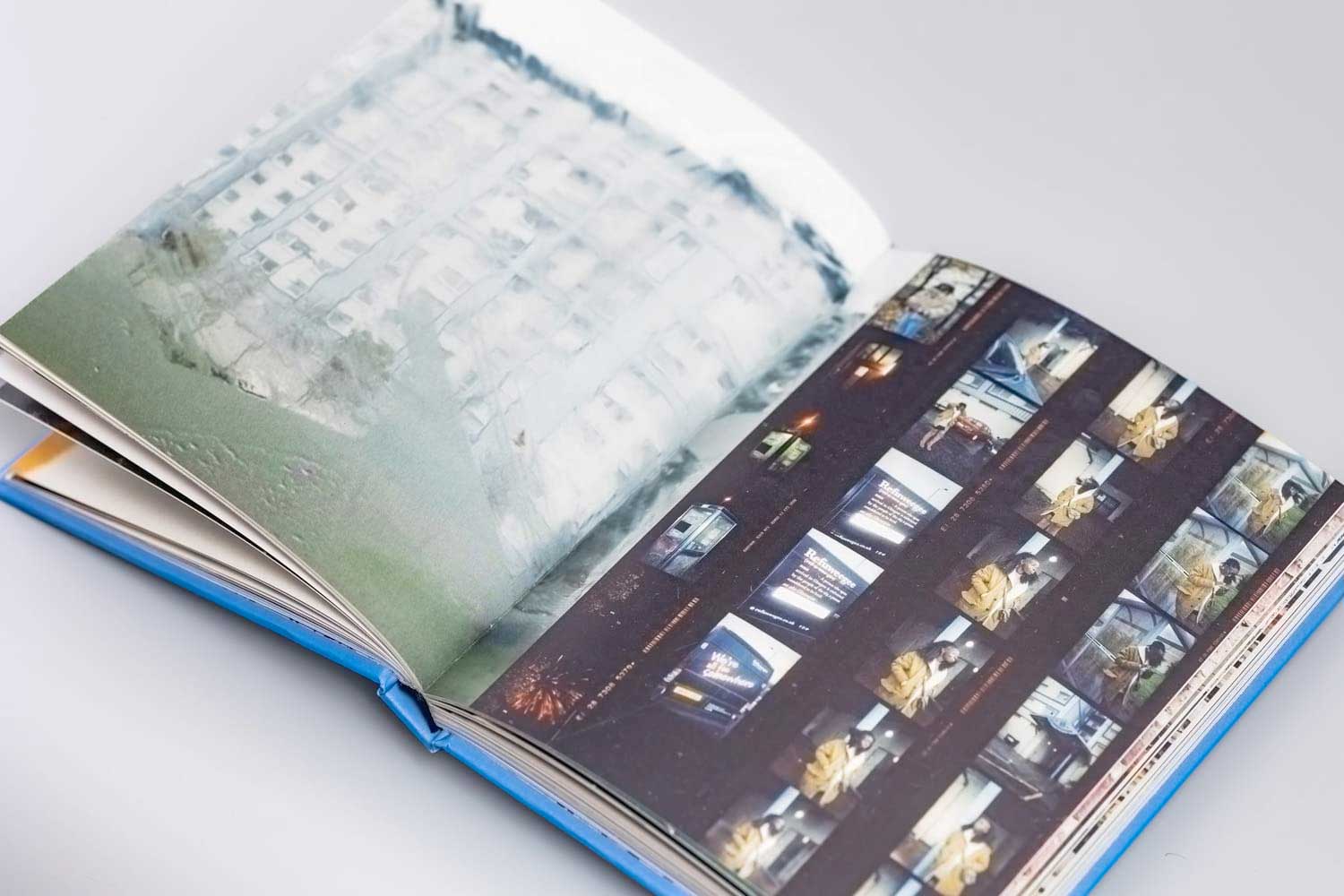

In a passage towards the end of the book Robinson shares Pitts’ theory about certain photographs, ones that don’t make it into family albums, that tend not to come to the fore. They represent ‘A manifesto of sorts based on the B-side of records being made in the spirit of culture, innovation and aesthetics rather than the economic demand for hits that can corrupt the purity of art.’

Throughout Home Is Not A Place the reader is confronted with pictures and words that uncover rarely told stories of Black experience. Lives that endure, that overcome, that dance without fear in the face of exclusion and economic hardship, that counter both casual and systemic racism with wit, energy, acumen and limitless expressions of everyday resilience, creativity and joy.

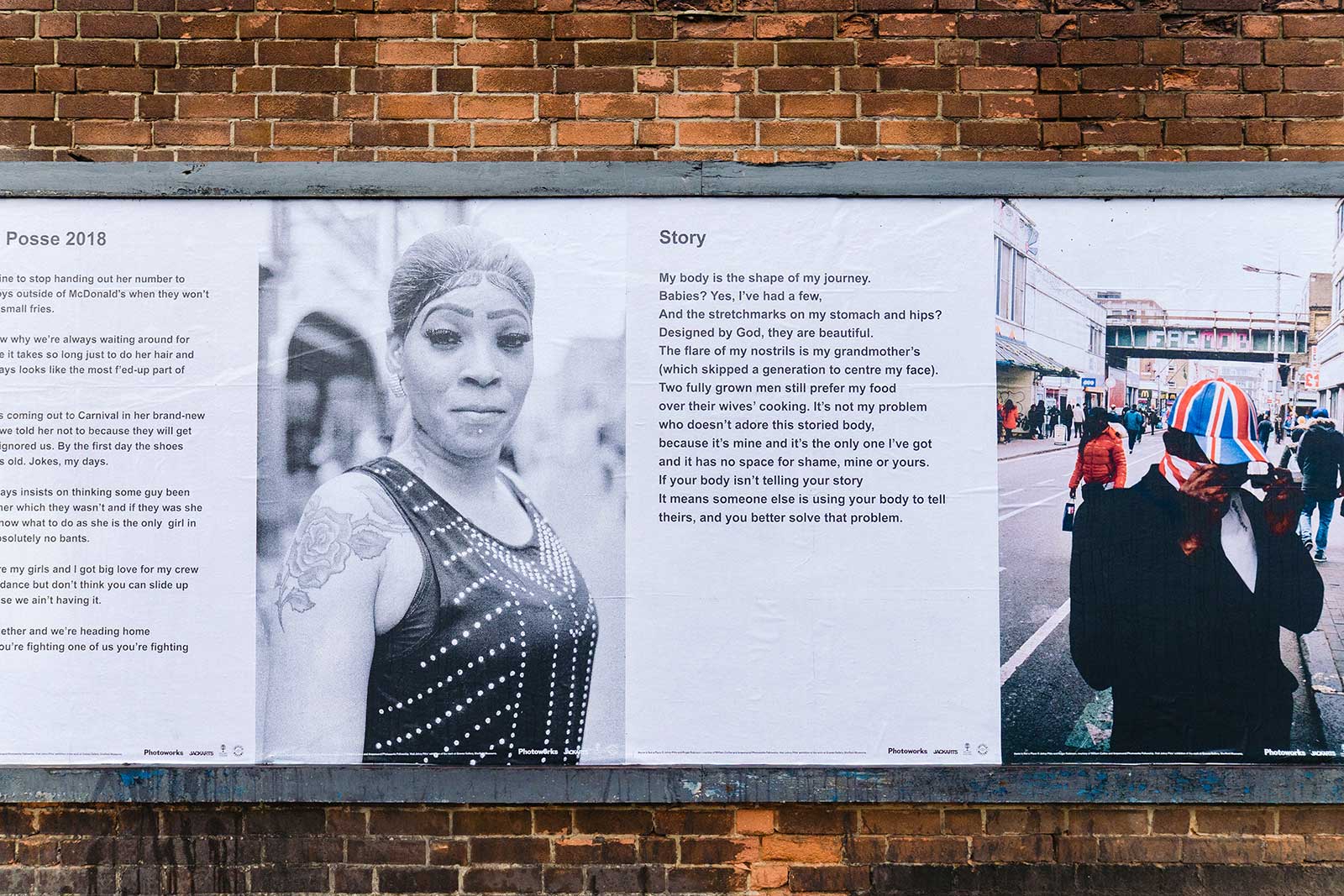

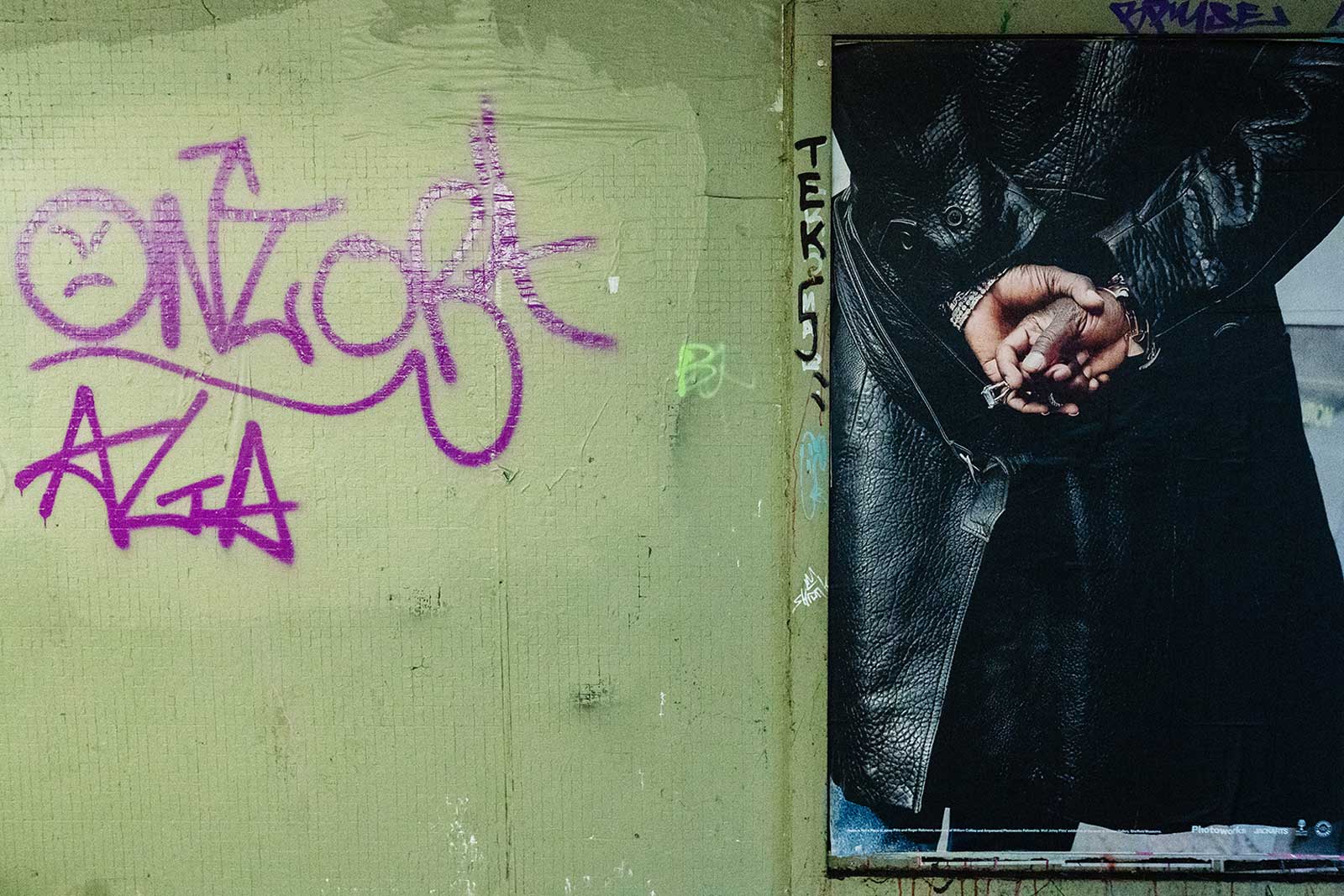

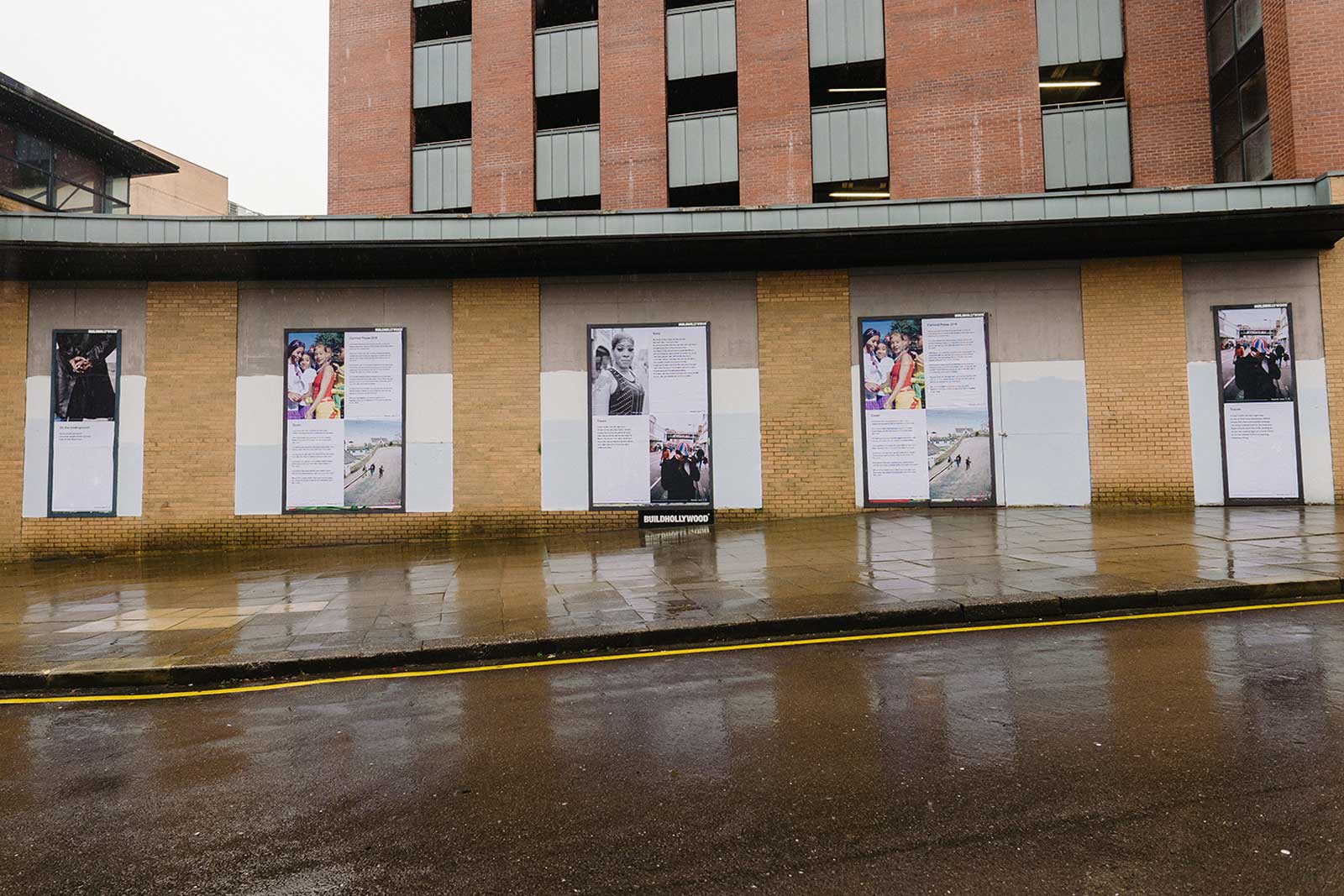

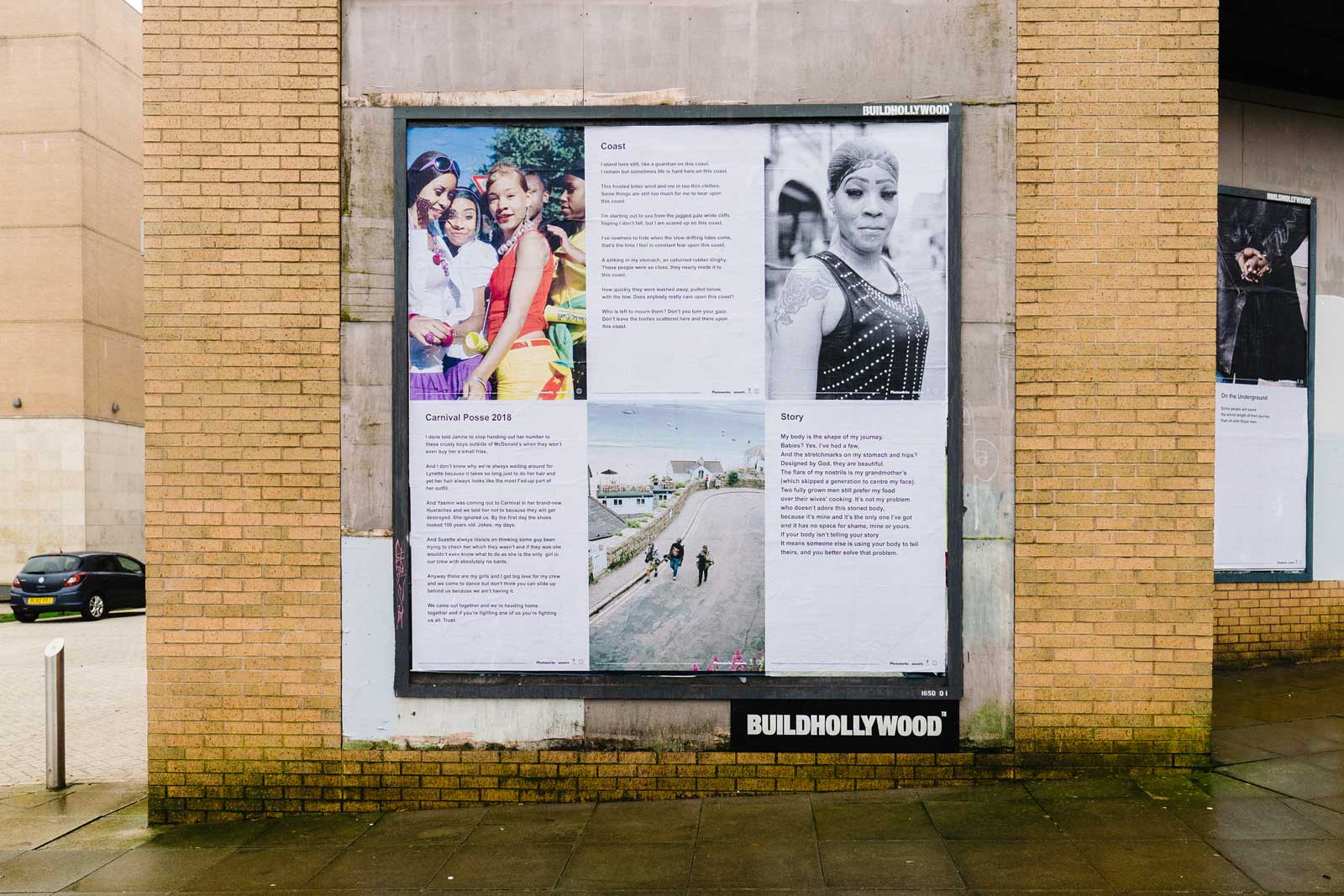

Pitts’ exhibition at Graves Gallery, Sheffield Museums continues until 24th Dec. 2022 before moving on to Stills Gallery, Edinburgh next year. Photoworks’ mission is to champion photography for everyone. In sharing Robinson’s vivid word pictures and Pitts’ rich visual poetry on display sites around the U.K. BUILDHOLLYWOOD are proud to help bring such timely and important work to as wide an audience as possible.