Your Space Or Mine

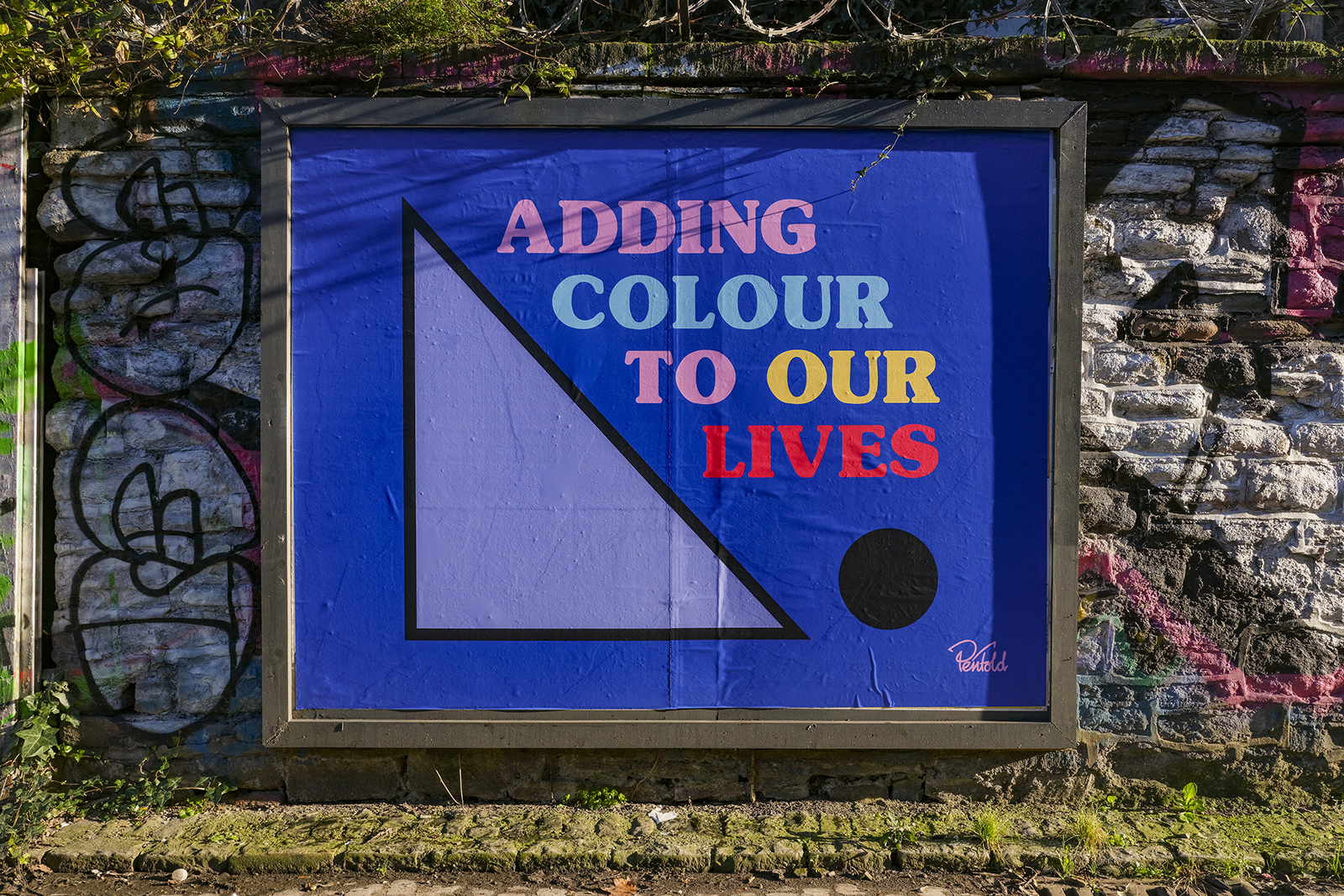

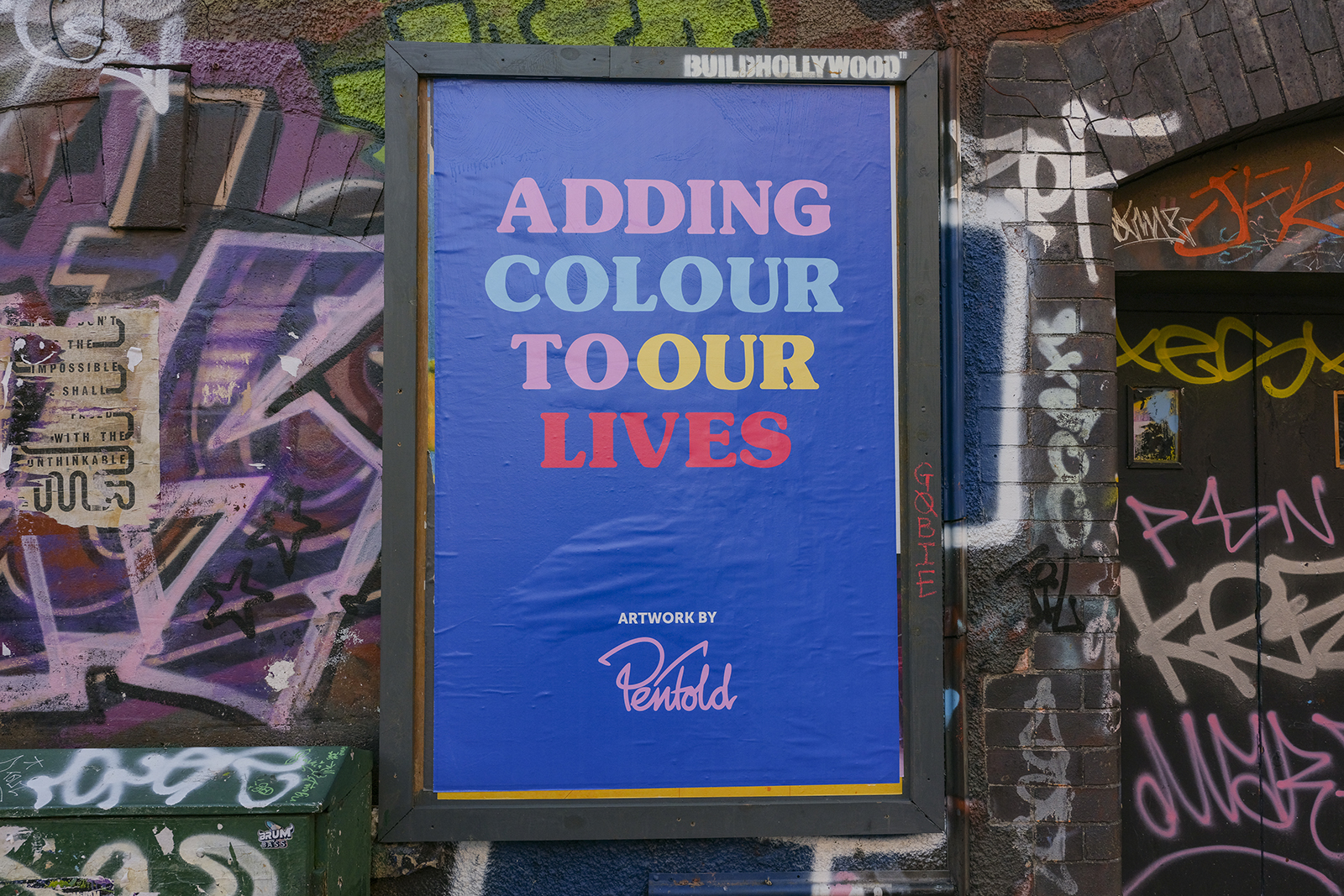

The world is losing its colour. Mr Penfold is painting it back.

“I’ve literally got albums on my phone full of colours I’ve seen out and about,” says Tim Gresham, better known as Mr Penfold. “Bins, lampposts, whatever. I just stop and take a photo of them. I think it’s how my brain works — it’s wired to notice that stuff.”

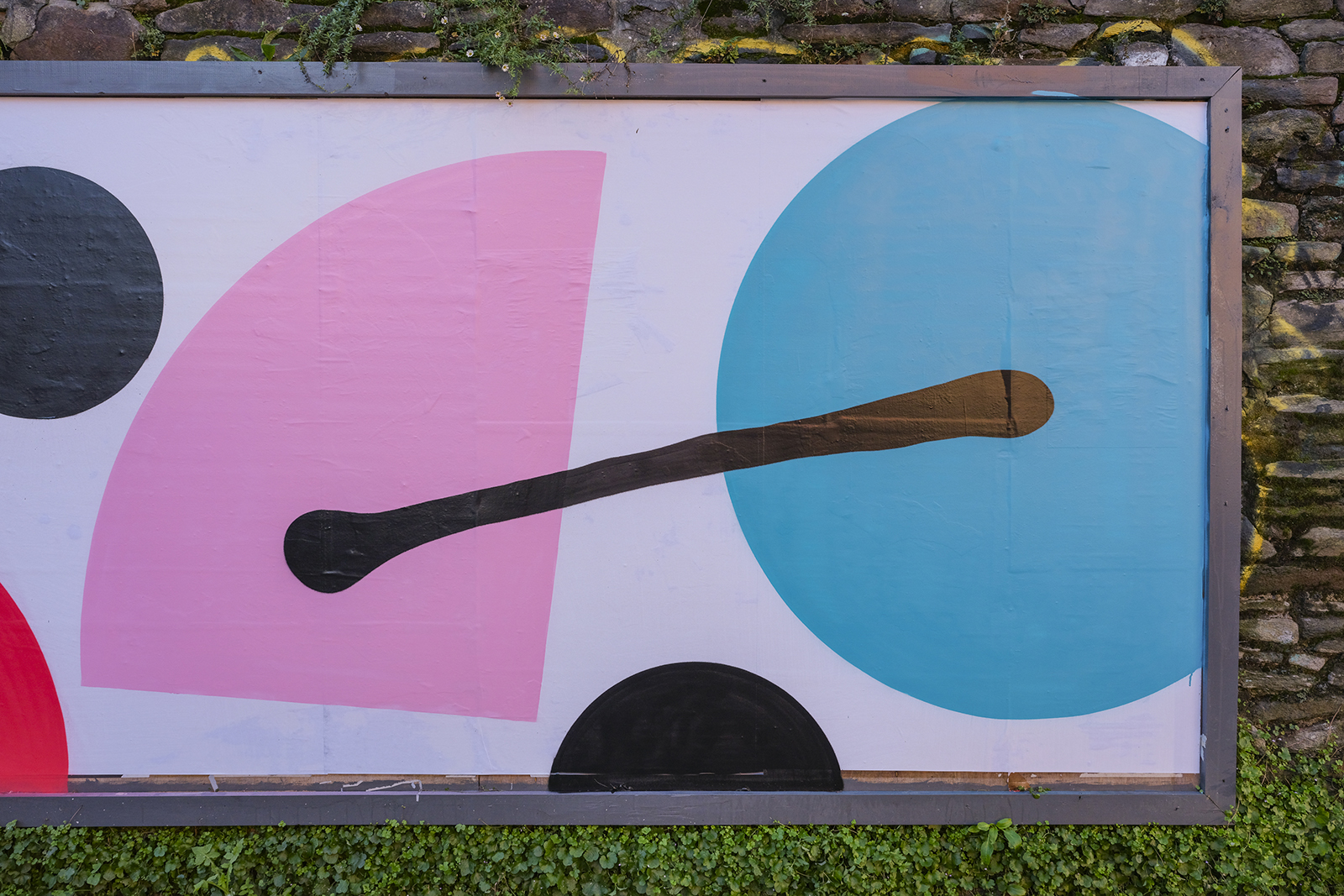

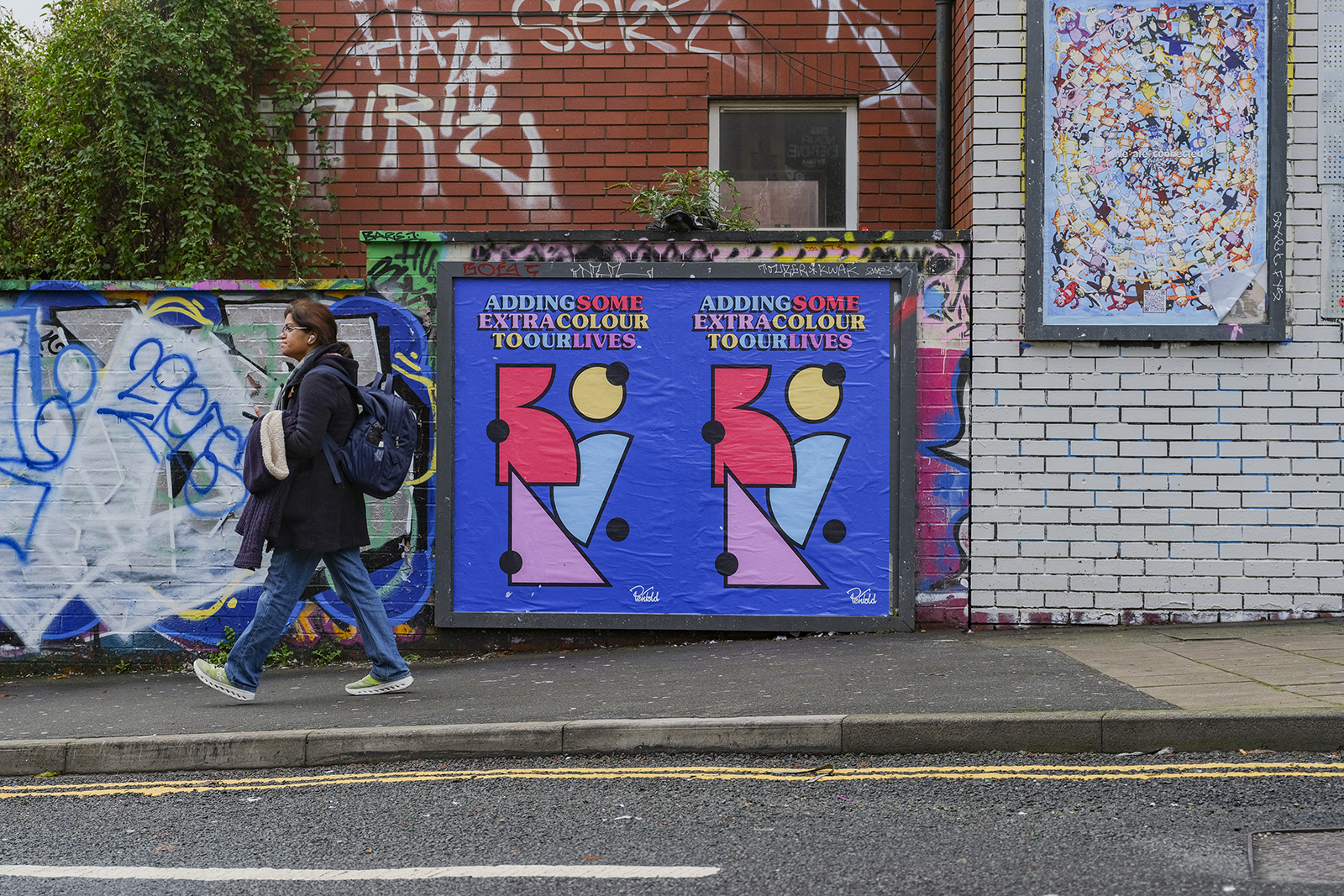

His art is as colourful as his camera roll. Having grown up in Cambridge but long since made Bristol his home, Gresham hasn’t so much carved out a career as an artist as he’s painted one — one vibrant shape, mural or installation at a time. Since picking up a spray can as a teenager, his work has pulsed with colour, movement and that unmistakable graphic rhythm rooted in skate culture and 80s-90s design. He’s been making art professionally for over a decade now, and his designs have only grown brighter while, in his eyes, the one around him has dimmed.

His latest collaboration with BUILDHOLLYWOOD, an enormous takeover at Bristol’s Lakota site, responds directly to a study that found the world is, quite literally, losing its colour. Researchers analysing thousands of consumer products from 1800 to the present day discovered a steady slide toward greys, blacks and whites. A global drift toward monochrome.

“You don’t really notice it happening” he says. “When we were younger, everyone had Burberry phone cases on their 3310s — now we’ve all just got black iPhones. No one wears brightly coloured socks anymore. It’s all white or black. You can feel it’s lacking.”

Gresham’s response isn’t political, nor ironic. It’s instinctive — a reminder of how colour makes us feel. “You made me question my whole life,” he laughs, when asked why the world needs more colour. “For me, it releases endorphins. If I walk past something and think, ‘Oh, that’s a nice colour,’ that gives me a buzz. It makes me feel good. It’s good for the soul.”

21.11.25

Words by