Partnerships

A love letter to Bristol’s nightlife: City’s creatives celebrate Bristol’s night time economy in new art book.

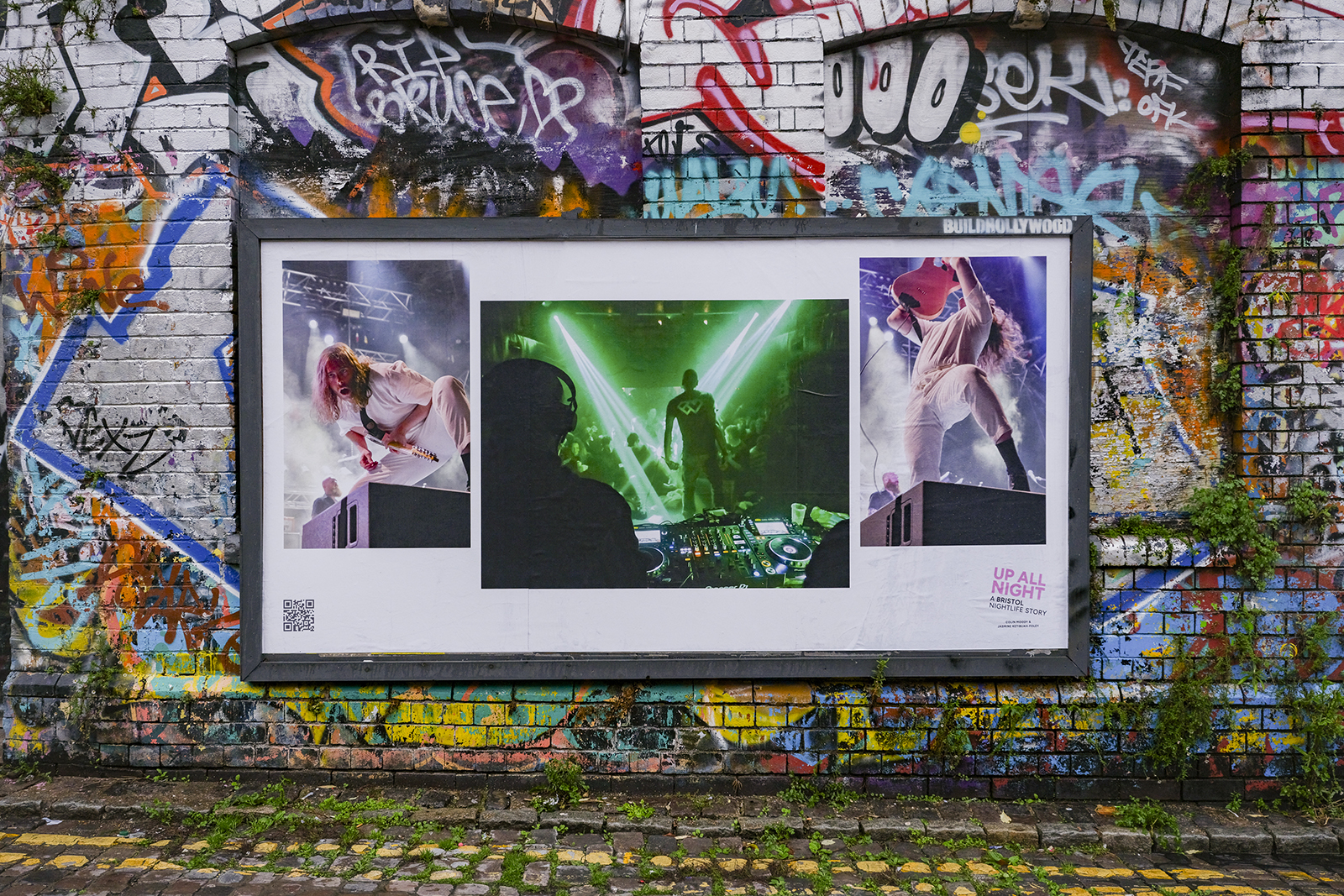

Two of Bristol’s leading creatives have joined forces with The History Press and JACK ARTS to launch Up All Night: A Bristol Nightlife Story – a vibrant tribute to the city’s after-dark culture.

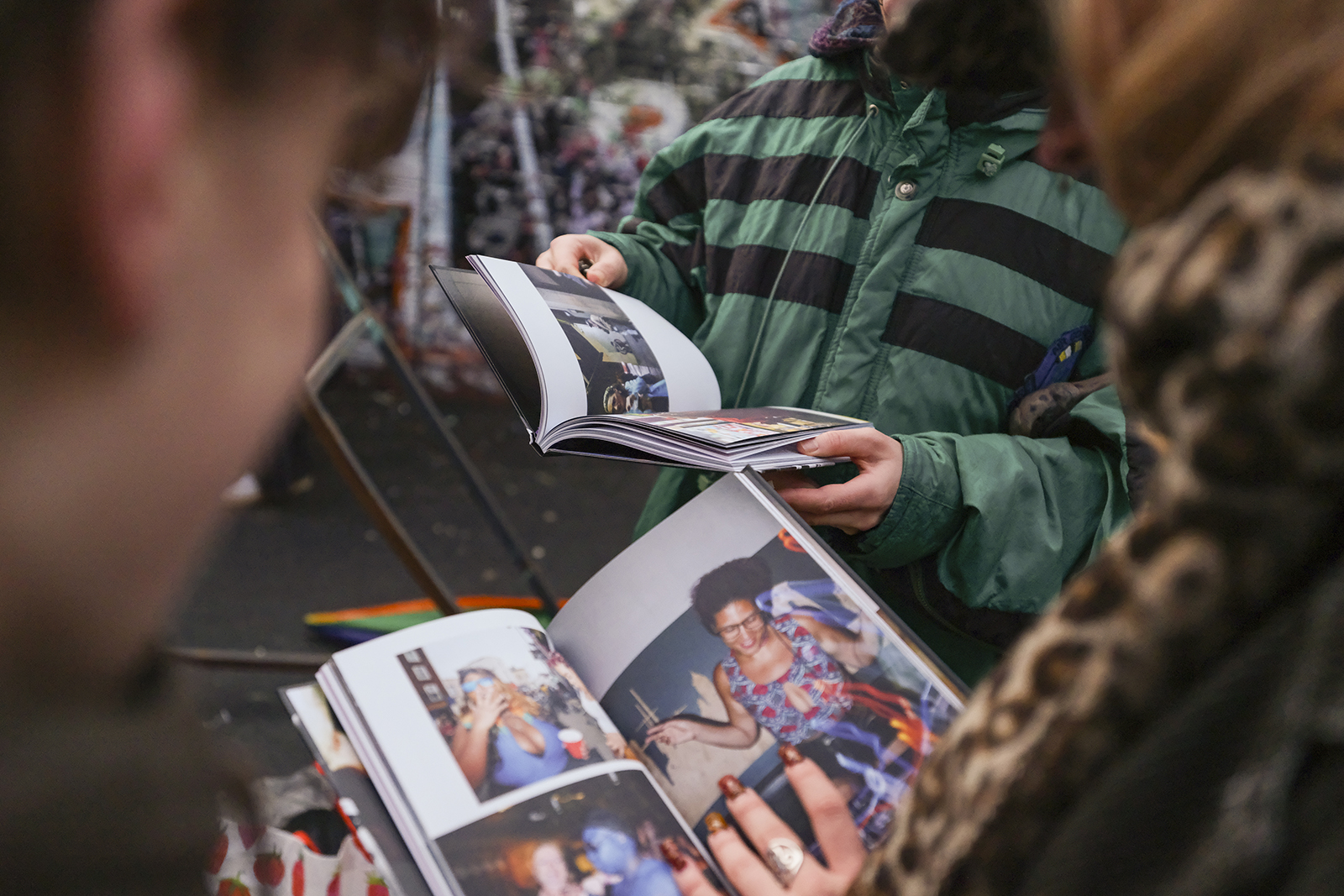

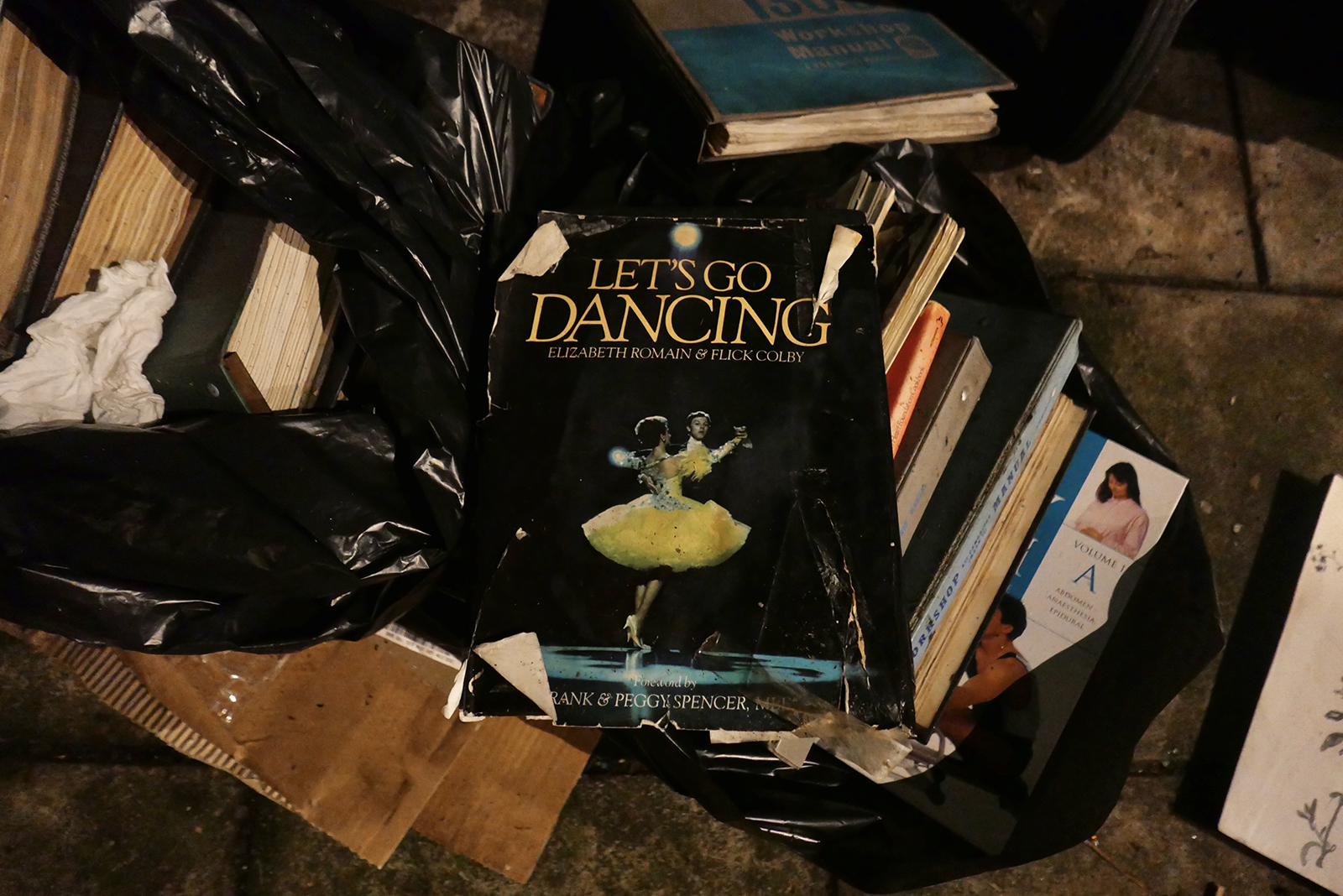

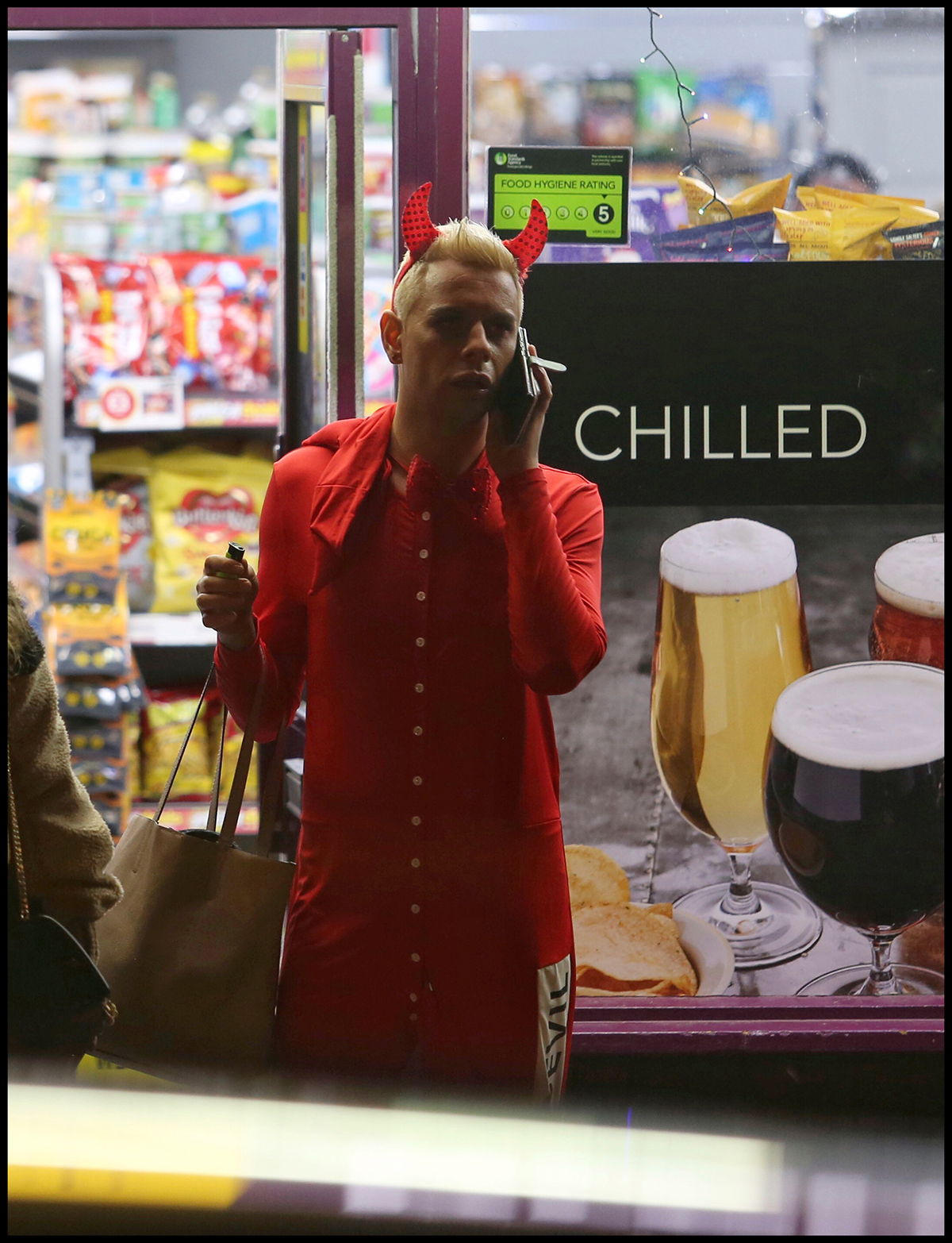

Created by award-winning photographer Colin Moody and writer/musician Jasmine Ketibuah-Foley, the book captures five years of Bristol nightlife through striking photography, personal reflections, and conversations with artists, promoters, and venue owners. Their collaboration grew out of real nights on Bristol’s dance floors, or as Colin puts it, “our own mini tribe,” a shared act of love and protection for the spaces that make people feel safe, creative, and connected.

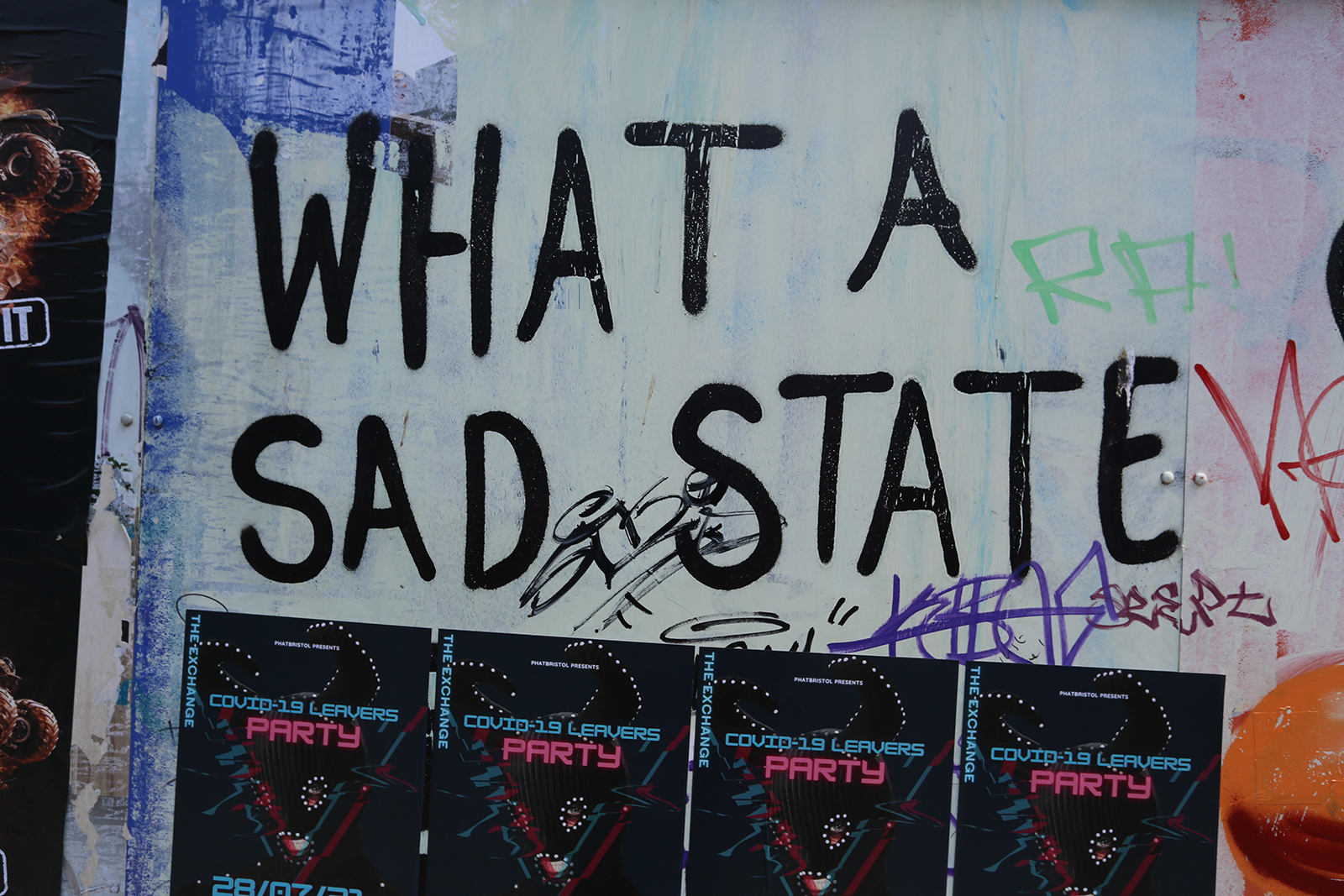

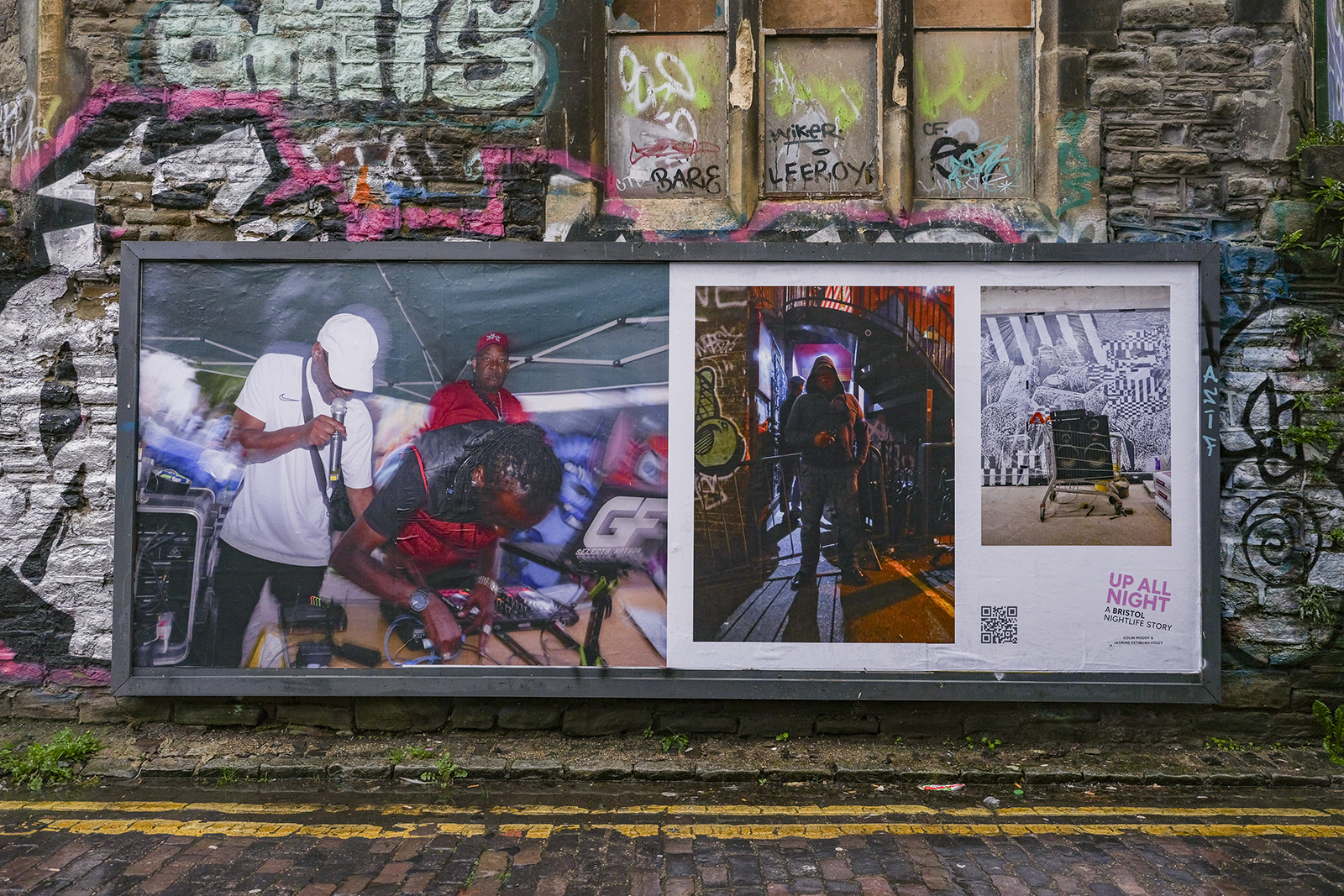

In a fitting celebration, the book’s artwork was unveiled at the iconic Lakota, one of Bristol’s most beloved and enduring nightclubs, providing the perfect backdrop for this homage to the city’s nightlife. The collaboration with JACK ARTS to exhibit the work outside Lakota was a deliberate choice, returning the images to the streets and communities that inspired them. “Displaying the book on billboards makes sense,” says Jazz. “Our story belongs out there on the night.”

We interviewed Colin Moody and Jasmine Ketibuah-Foley, the creative duo behind Up All Night: A Bristol Nightlife Story. They discuss the passion driving their “love letter” to Bristol’s club culture and the power of art to capture community spirit. From dance floors to billboards, their project celebrates the city that never stops moving.

05.11.25

Words by