Partnerships

The Guerrilla Girls feminist call to action is coming to a billboard near you

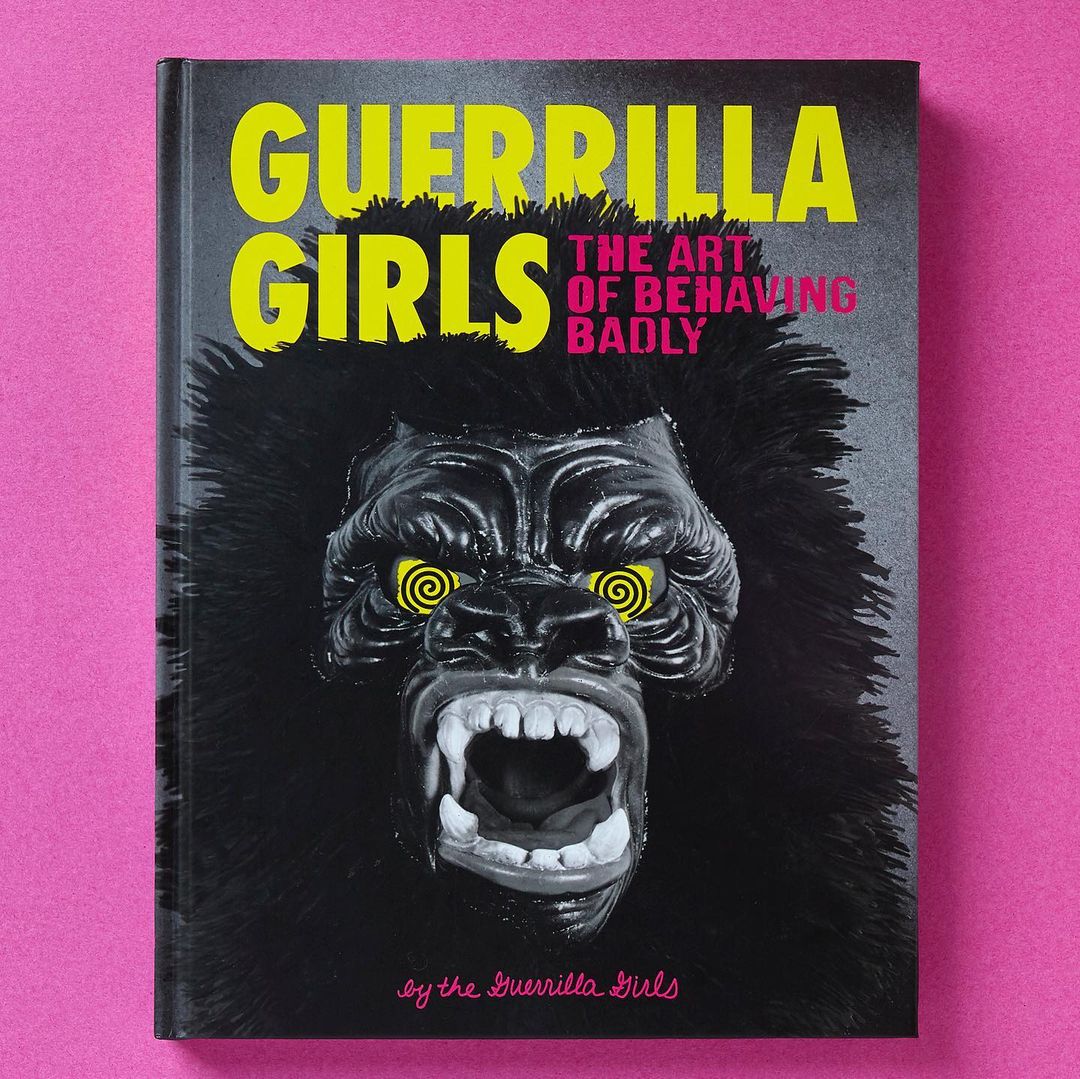

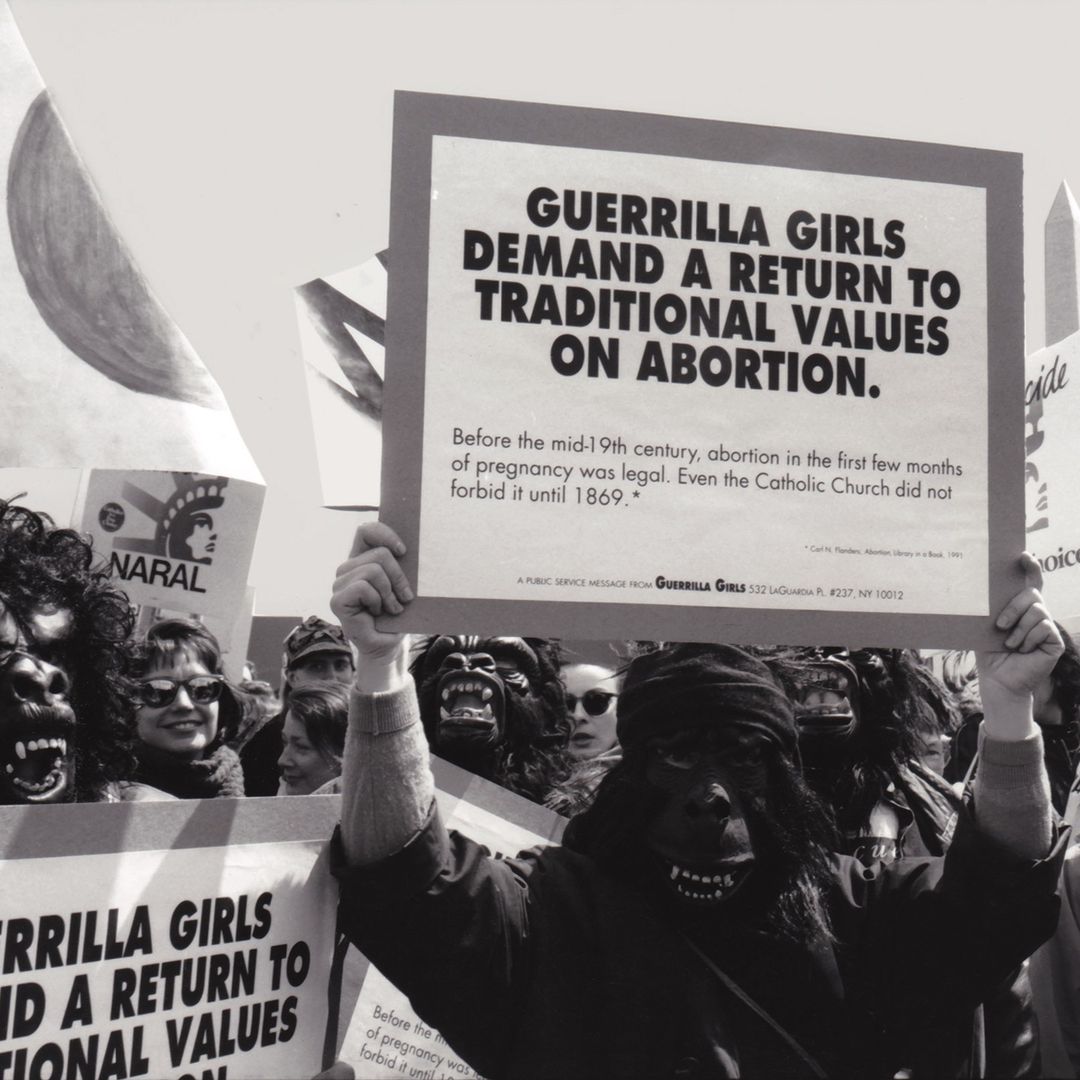

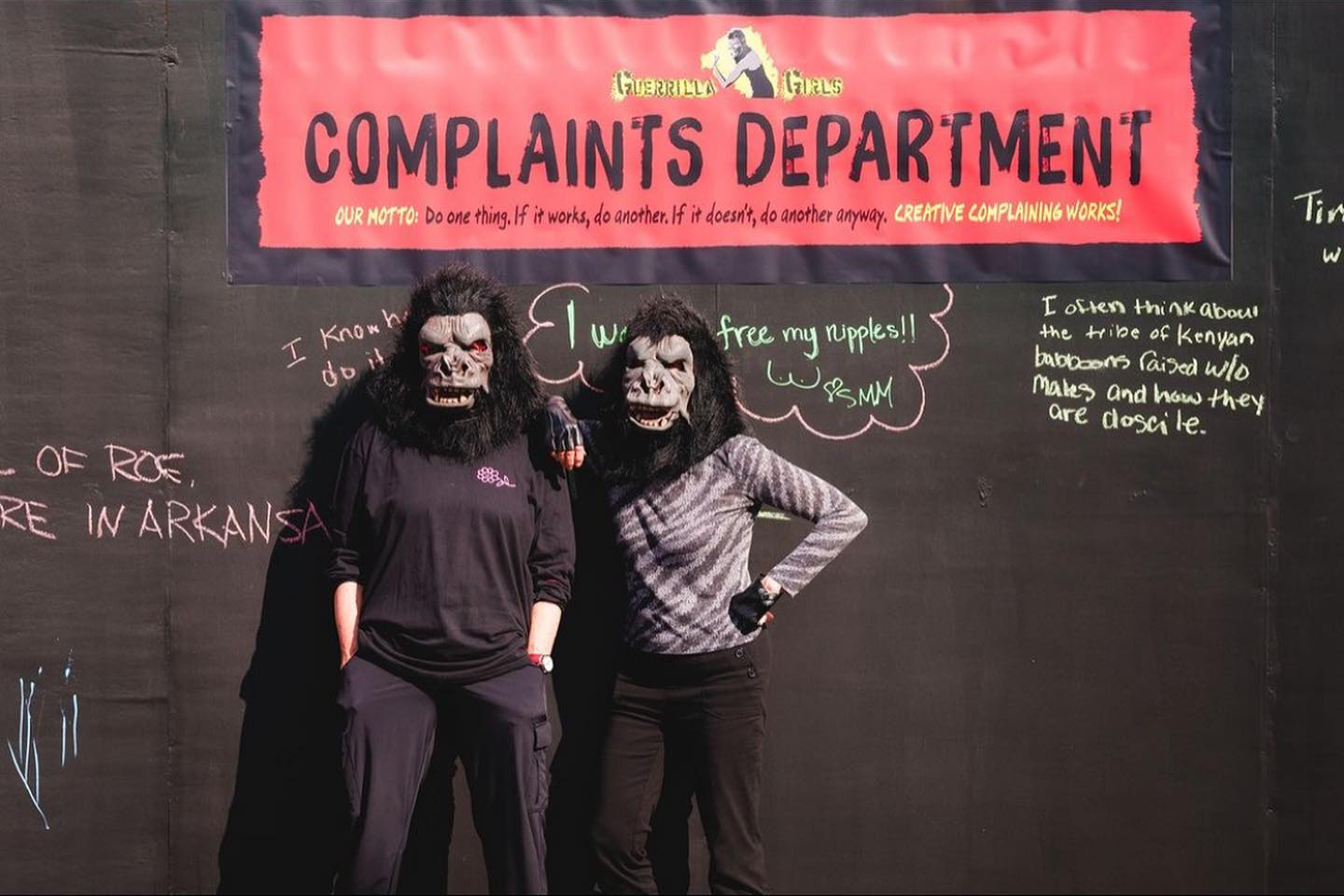

In her book Feminism, Interrupted: Disrupting Power, the feminist writer and researcher Lola Olufemi emphasises the liberatory potential of art, proclaiming that “Art is best utilised as a weapon, a writing back, as evidence that we were here”. Olufemi shares this perspective with the gorilla mask-wearing feminist art collective the Guerrilla Girls, who, through their structural critique of the art world, have reiterated the power of art to alter social and political consciousness.

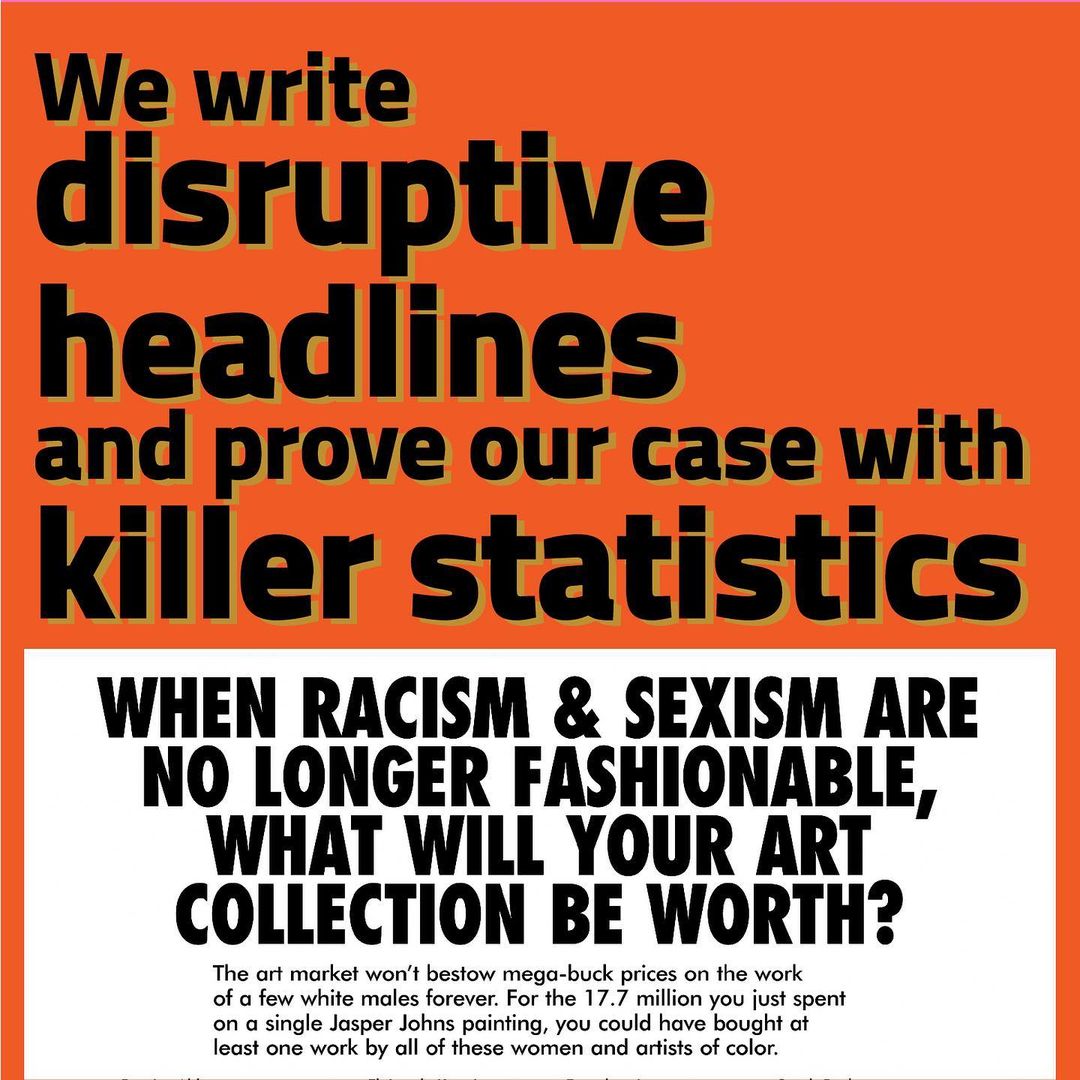

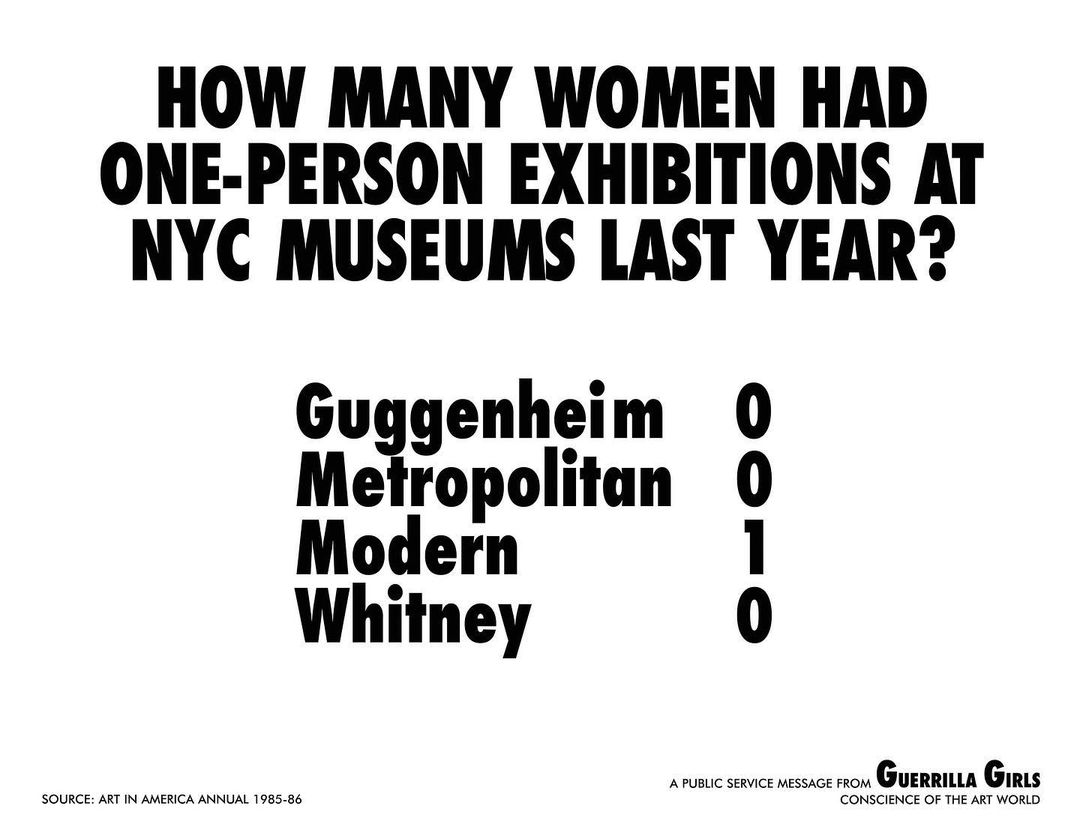

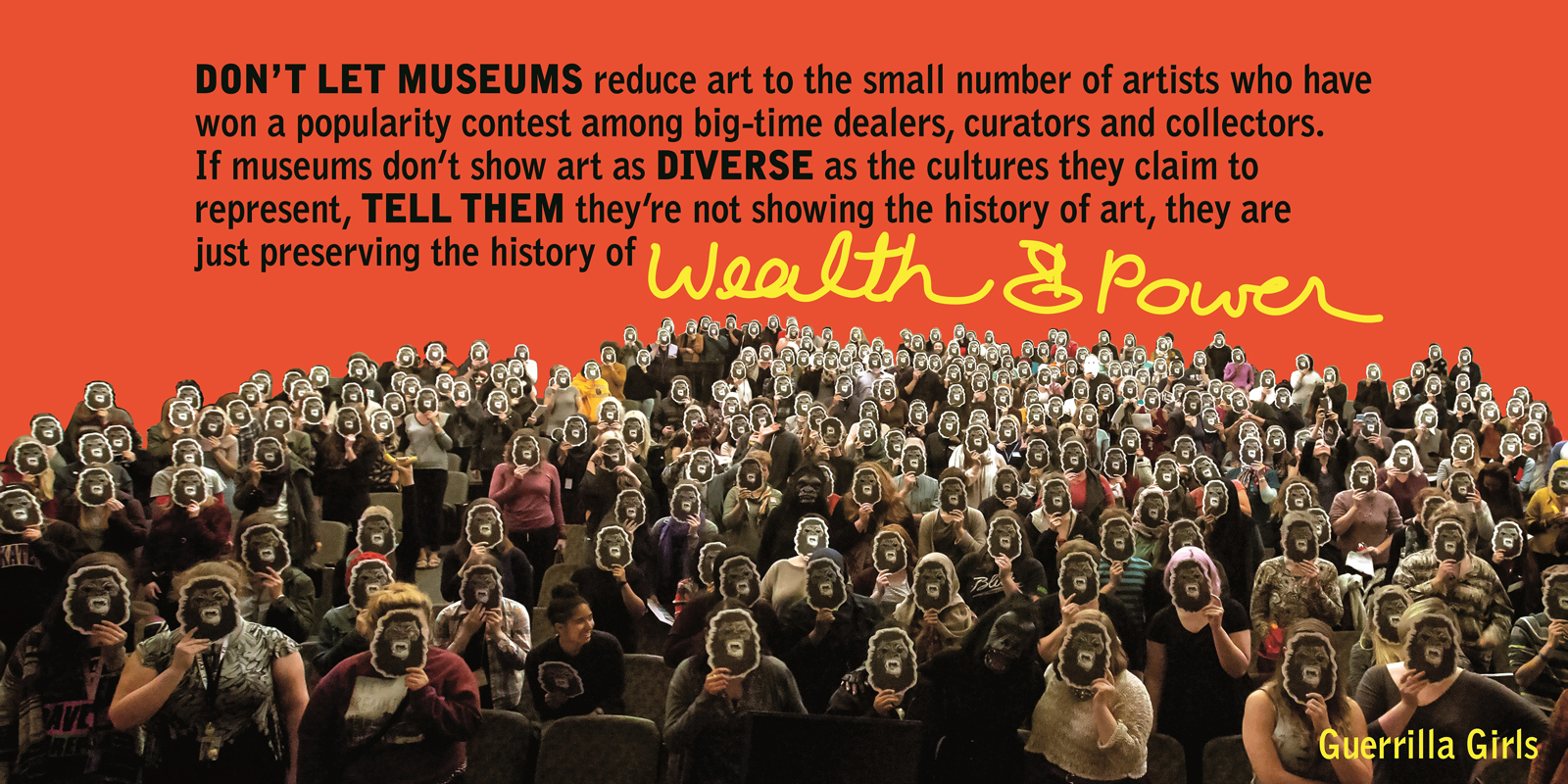

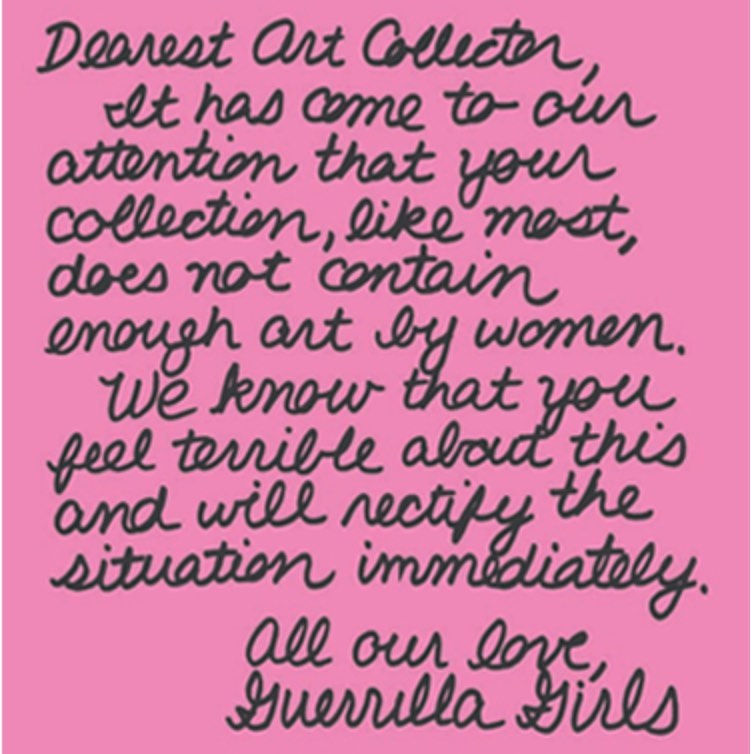

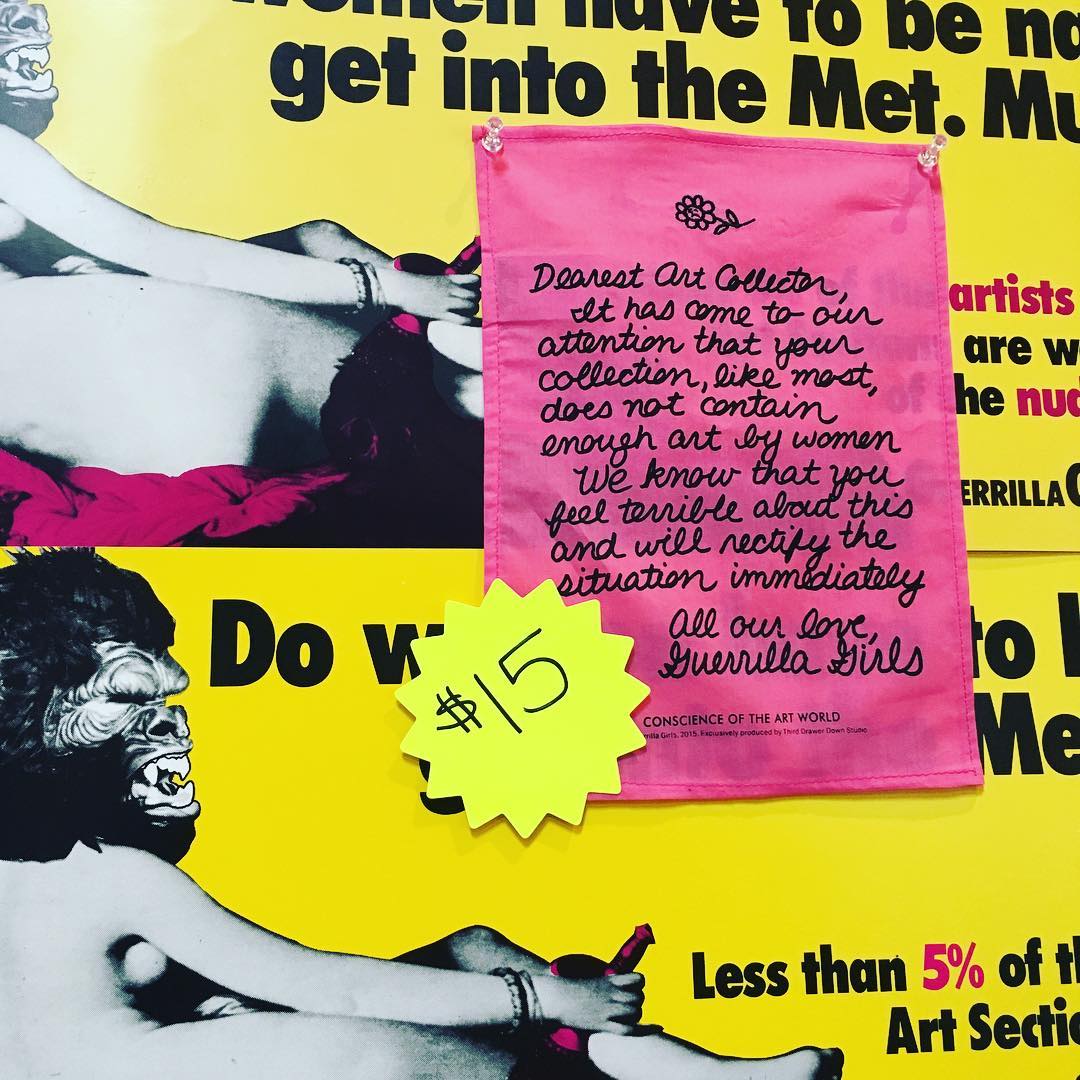

Beginning in the 1980s, its founding members, who go by the aliases Frida Kahlo and Käthe Kollwitz after the great women artists, have produced spectacular posters that confront the shortcomings of some of the biggest museums in the world. In 1989, their screenprint of Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get Into the Met. Museum?, which featured a painting by Jean-Auguste-Dominique modified with a gorilla mask, stated with staggering clarity the state of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s modern art collection, where ‘less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female’. Other posters recounted, with the Guerrilla Girls’ trademark satirical bite, the abysmal collections of commercial galleries in New York that primarily represented white male artists.

Their influence on the contemporary art world is immeasurable, and many art enthusiasts go so far as to call them ‘art world royalty’. A term that is perhaps too antiquated for the Guerrilla Girls’ taste, whose goal has always been to democratise art, away from billionaires and museums who concertise ideas of taste and quality based on their private collections. Their anonymity, which began as a safety measure to protect their members from the vitriol of the art world, is now their superpower, shares Frida. “I think our anonymity intrigues people and draws them in. As we are artists, the masks also ensure that our message and politics aren’t obscured by what people think of our personalities and our art.”

21.02.24

Words by