Your Space Or Mine

A field of vision: Rob Jones’ photographs of UK festivals go large

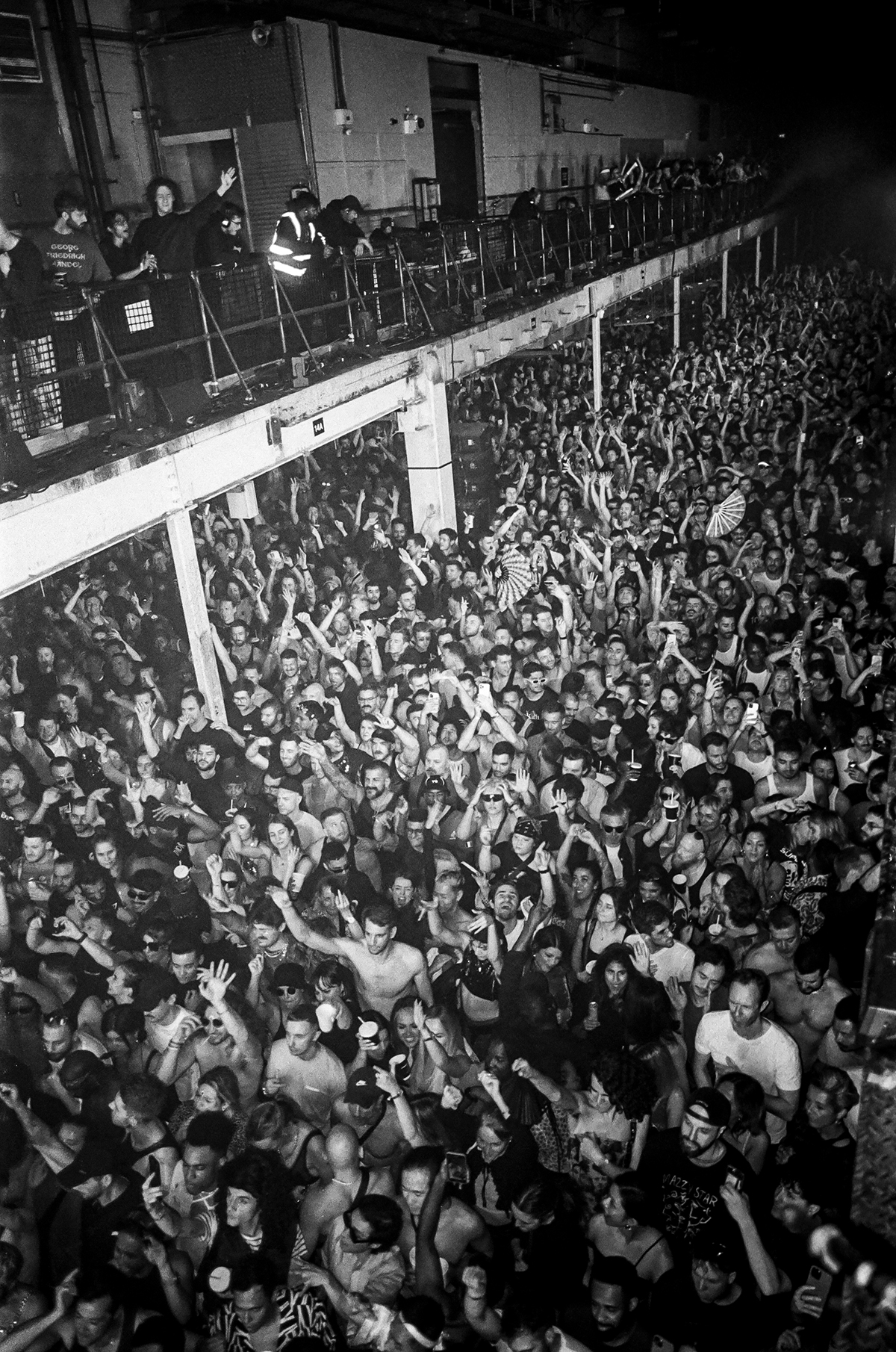

The dancefloor in British culture has always been varied and ever-changing, from tiny basements and vast industrial spaces to urban street parties and carnivals. In the ‘90s festivals like Tribal Gathering and The Big Chill transformed free party and club energy into a festival format, with gatherings including Bestival evolving the interface between club culture and big stages in fields by the mid 2000s. An explosion of festivals followed and by 2016 it was estimated that between 800 and 1000 festivals were taking place in the UK.

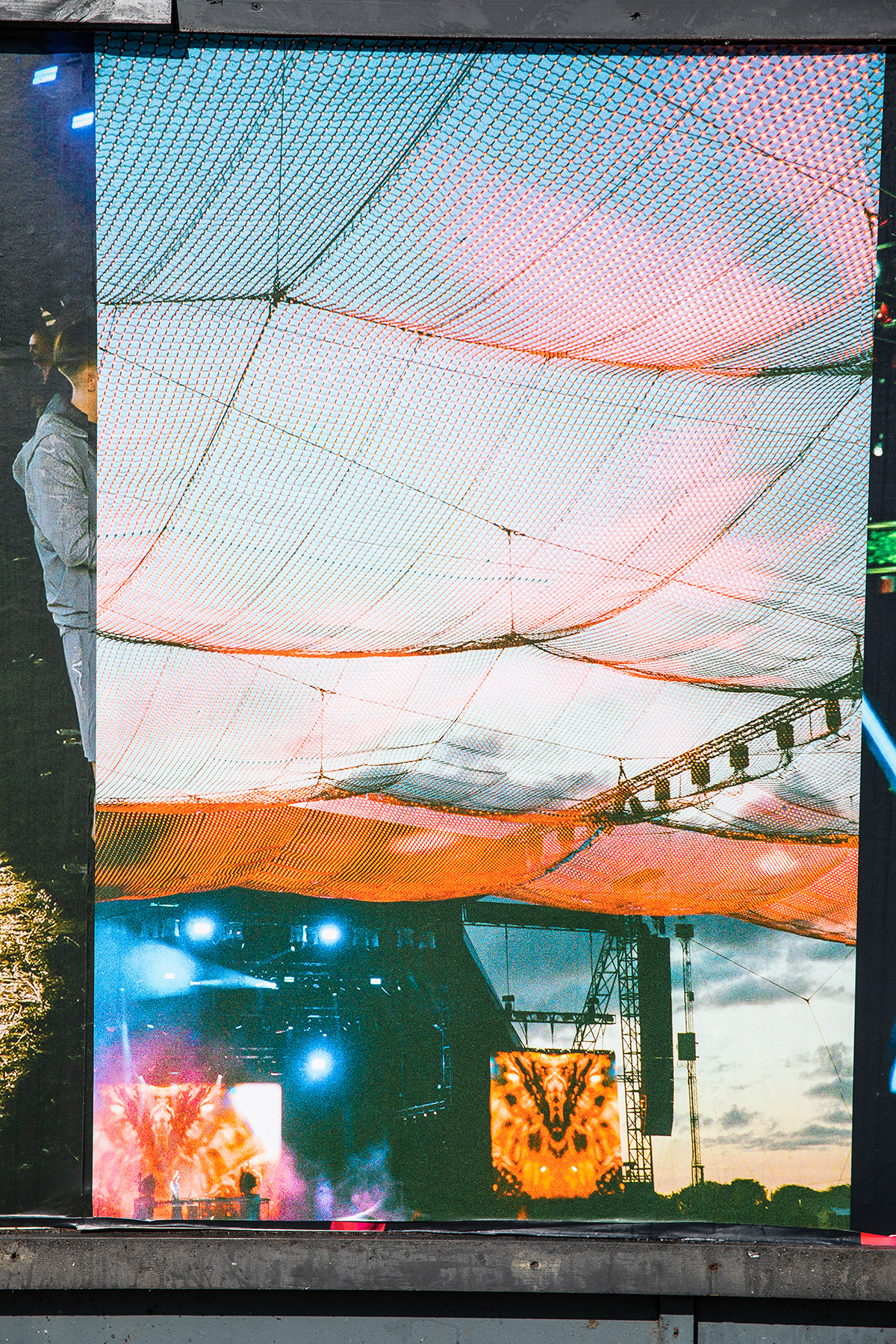

It’s a hard time for all forms of collective, communal celebration, whether that’s physical venues struggling with rising costs, issues with property developers and noise-averse neighbours or almost everyone dealing with the spiralling cost of basics. However, good times will be had, and festivals provide an annual celebration, whether that’s something free and local, or big ticket moments like Glastonbury where audiences and artists alike can switch off and tune into their favourite forms of music and culture.

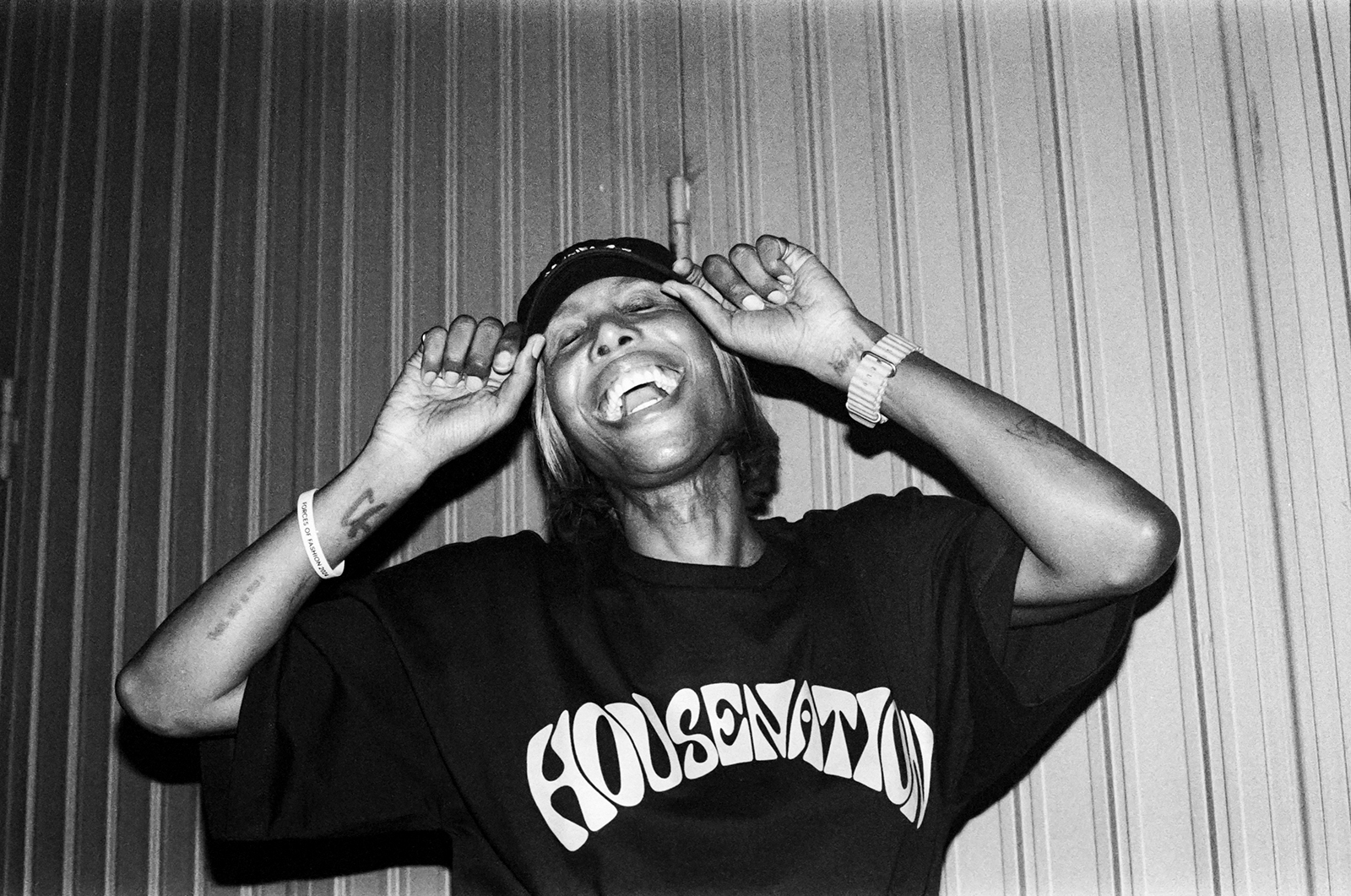

“Festivals and club culture, they provide a common ground for people,” says photographer Rob Jones, who has been creating iconic images of the dancefloor since 2015. “Everyone’s there for the same reason: the music and the emotion that comes with it. It’s so positive.”

During the pandemic, the photographer and co-founder of Khroma Collective with Jake Davis, photographed over 40 of London’s most iconic nightclubs and venues whilst they were closed. Shot at night, the images provide a time capsule both of a shared moment when going out wasn’t possible and of music venues in the capital city at that time.

02.05.25

Words by

Drumsheds

Drumsheds

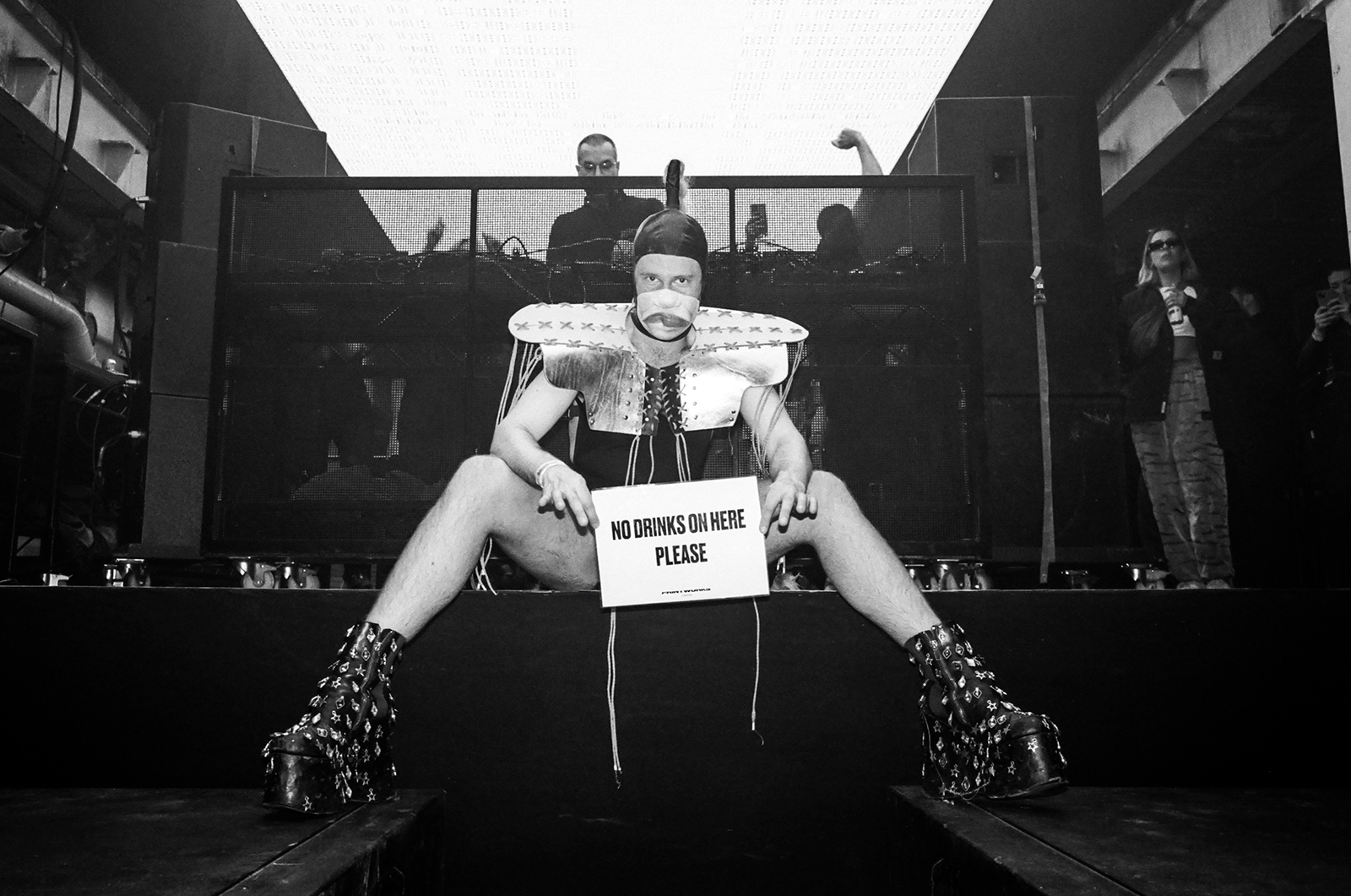

HOMOBLOC

HOMOBLOC

HONEY

HONEY

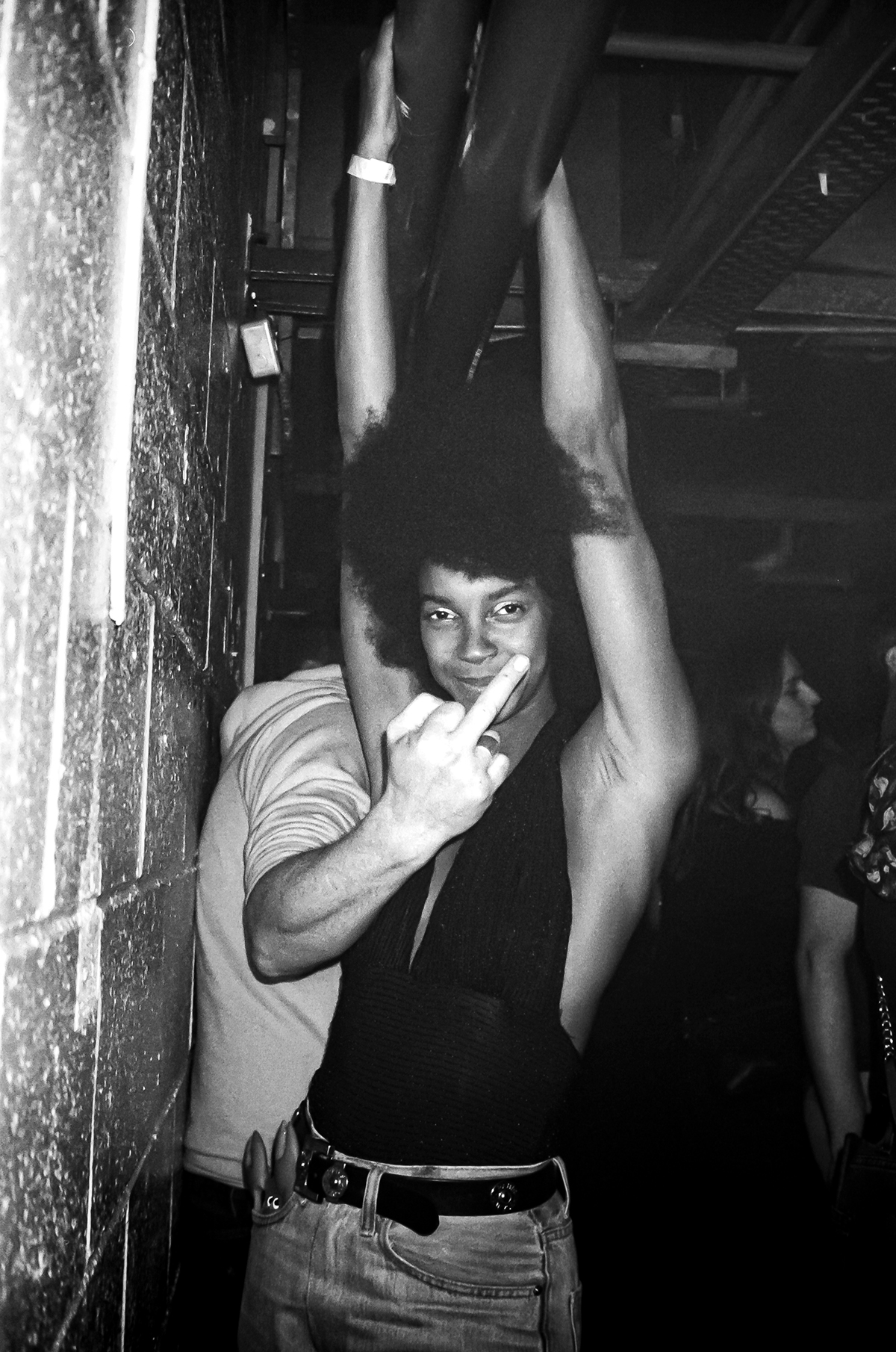

HOMOBLOC

HOMOBLOC

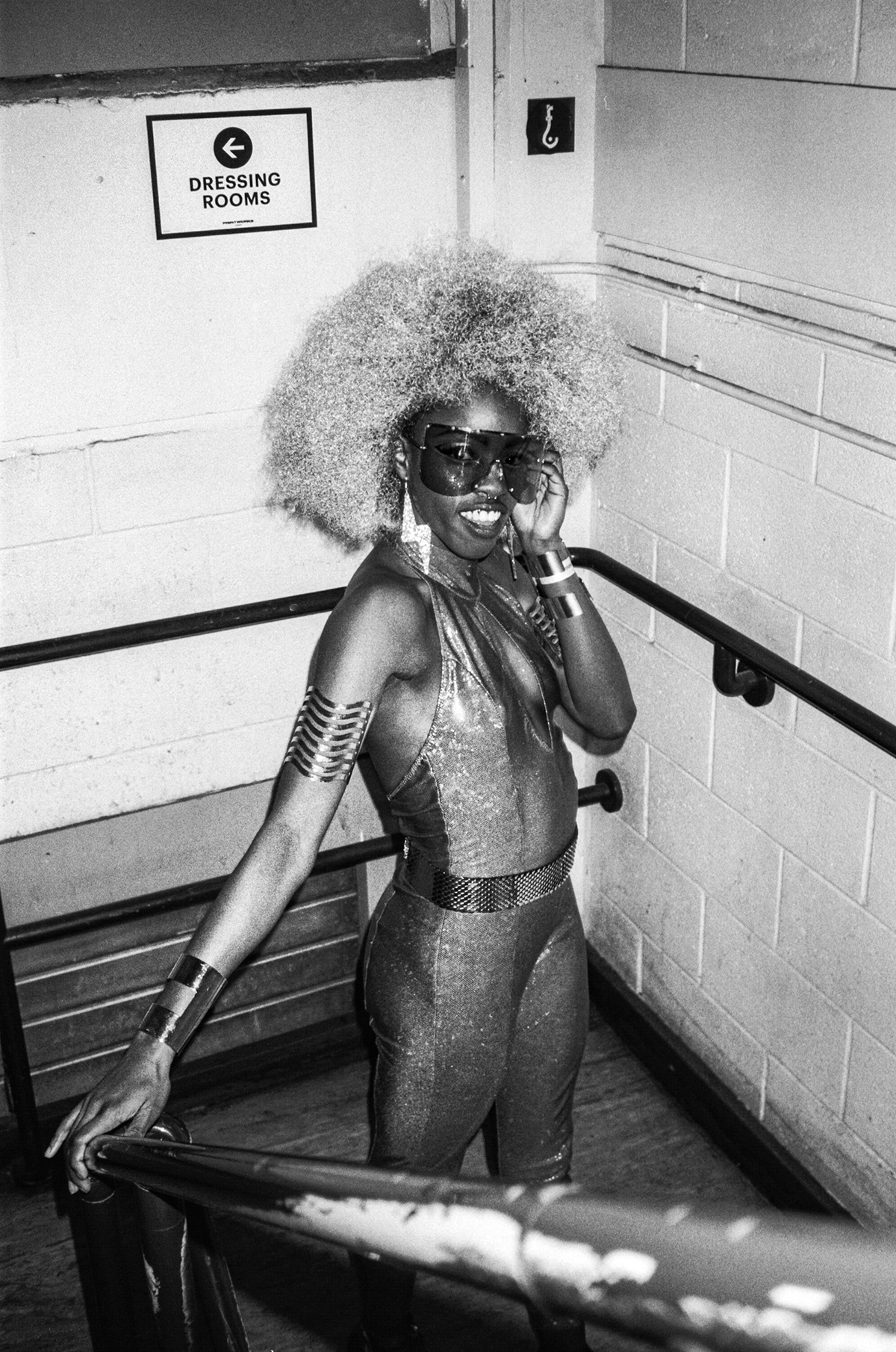

GALA

GALA