Partnerships

How going ‘Blind at The Age of Four’ inspired musician and fine artist GAUNT’s debut album and exhibition.

Great art teaches us about being human and GAUNT’s work is a crash course in the subject.

Through the sheer amount of ways to interact with Blind at The Age of Four – the album, the paintings, the performances, the exhibition, the billboards – you can learn a lot about the beauty of life’s abstraction, the importance of making art and culture accessible, the artist in question’s childhood and, maybe even your own experiences.

Growing up in an area of Cambridgeshire he describes as ‘the middle of nowhere,’ Jack Warne’s childhood is timestamped by spells of blindness. Caused by a rare, hereditary disease called Thiel–Behnke dystrophy, his experience of the condition, and the way he interprets the world as a result of it, is as integral to the all-encompassing project as the name would suggest.

Blind at The Age of Four is the debut album from the producer and fine artist, but it’s more so a world that he’s been building since he moved to London. GAUNT not only creates crunchy, electronic textures in music, he also puts them into a painted, full collection of warping, physical and digital art that will be exhibited at 39 Gransden Avenue in Hackney throughout September and October.

Header video by Jack Warne

26.09.23

Words by

Culy nad Leimy © D/ARTS

Culy nad Leimy © D/ARTS

39 Gransden Avenue © D/ARTS

39 Gransden Avenue © D/ARTS

Ulcy Rptresnse Het Flim © D/ARTS

Ulcy Rptresnse Het Flim © D/ARTS

39 Gransden Avenue © D/ARTS

39 Gransden Avenue © D/ARTS

39 Gransden Avenue © D/ARTS

39 Gransden Avenue © D/ARTS

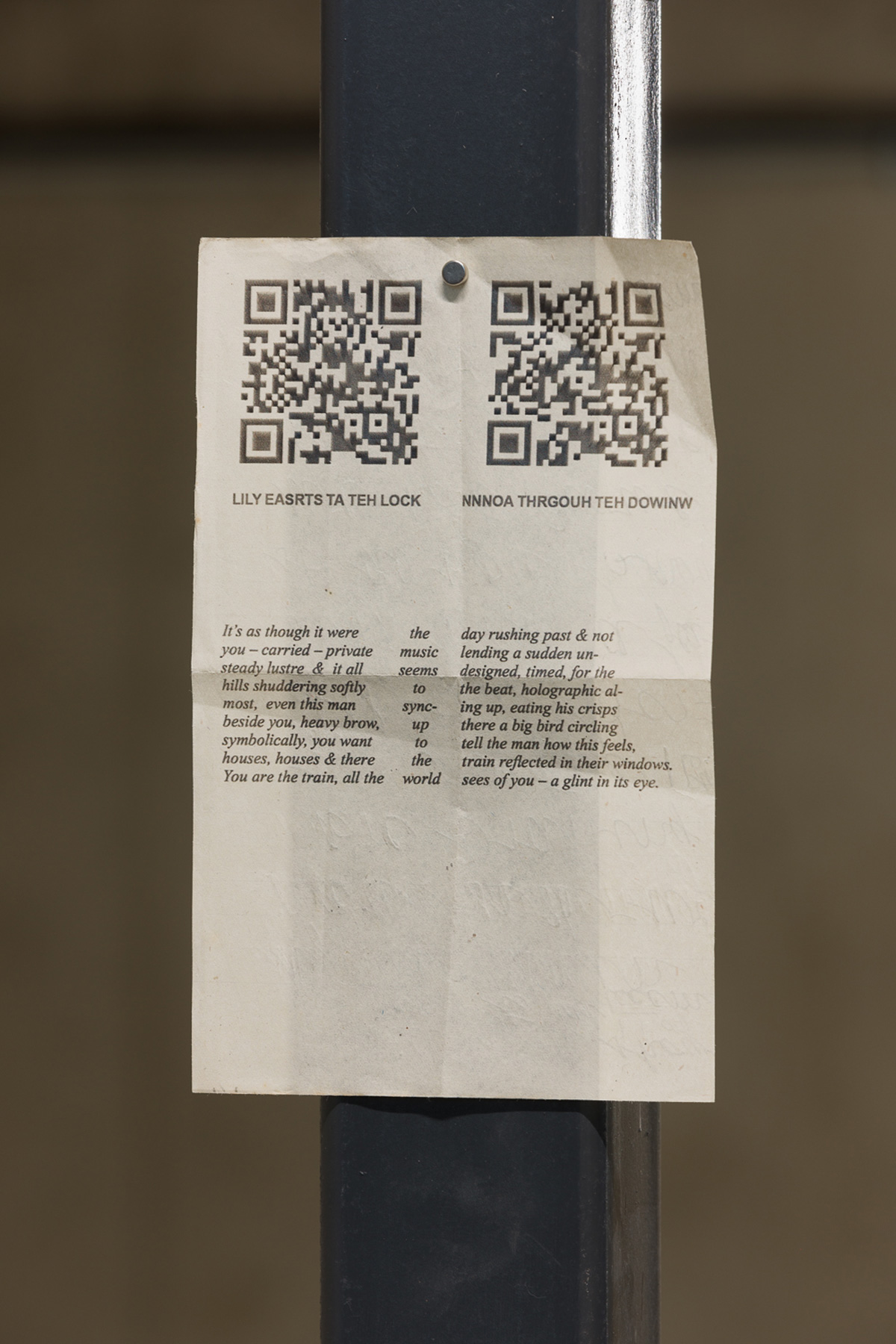

Left: Lily Easrts ta Teh Lock / Right: Nnnoa Thrgouh Teh Dowinw © D/ARTS

Left: Lily Easrts ta Teh Lock / Right: Nnnoa Thrgouh Teh Dowinw © D/ARTS

Blind at The Age of Four private view © D/ARTS

Blind at The Age of Four private view © D/ARTS