Your work is often found in unexpected places, from galleries and exhibition spaces to shopfronts and side streets. Why is it important for you to create art for everyday spaces? How does this translate to BUILDHOLLYWOOD’s 1 Quaker Street (The Sandbox) and Mare Street locations?

Part of not feeling belonging or being part of a space means that you must go where you can show things. I found this through what was called installations and then in terms of public/land art and raves when I was in Cornwall. I think graffiti work and the fact that you can get all people to see what you can do and think in the public space has always been important coming from Birmingham, particularly with artists I looked up to such as Kafiat Shah, who would hand paint shop signs, and Zuki and Juice 126 who created abstract graffiti and painted on objects as well as walls.

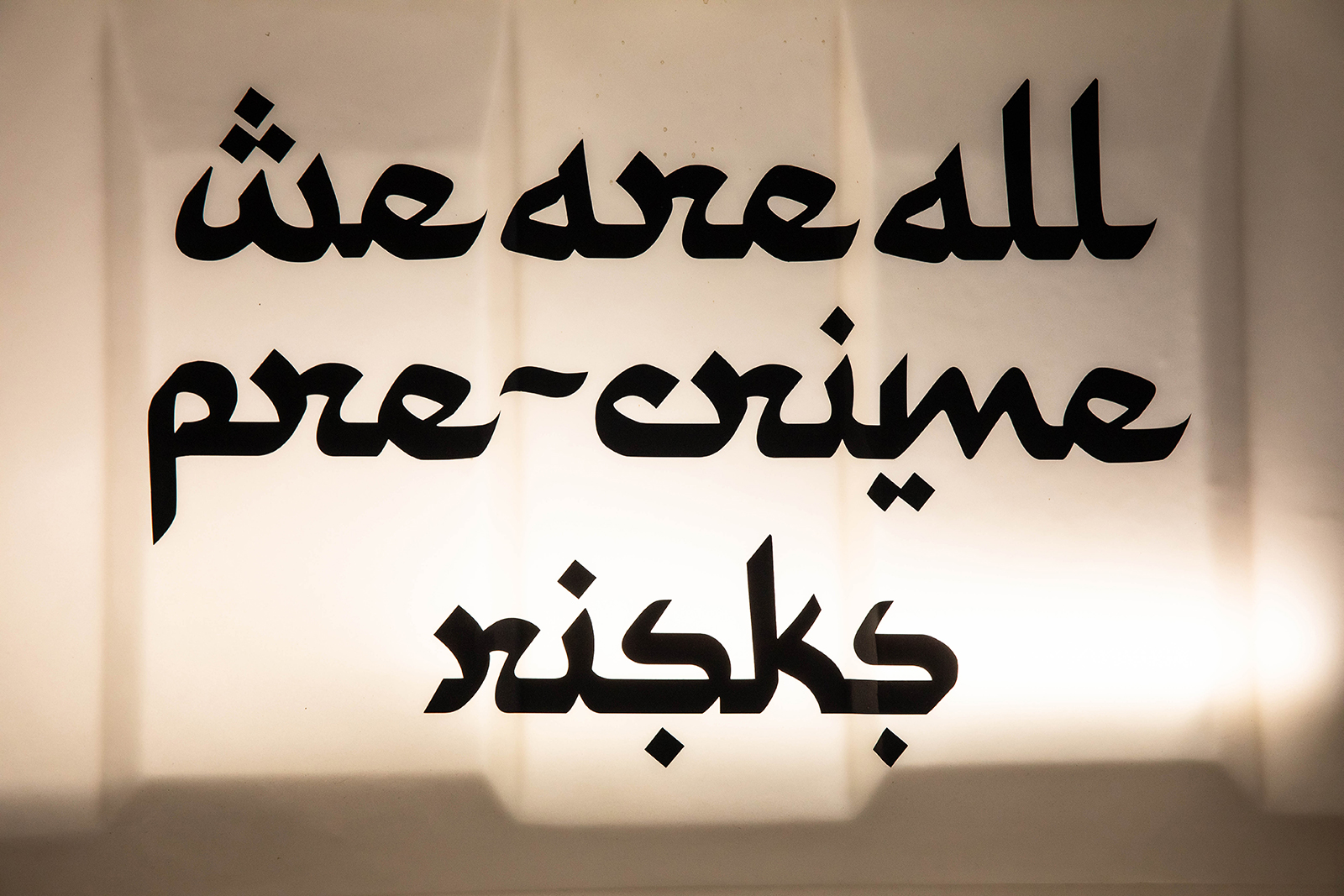

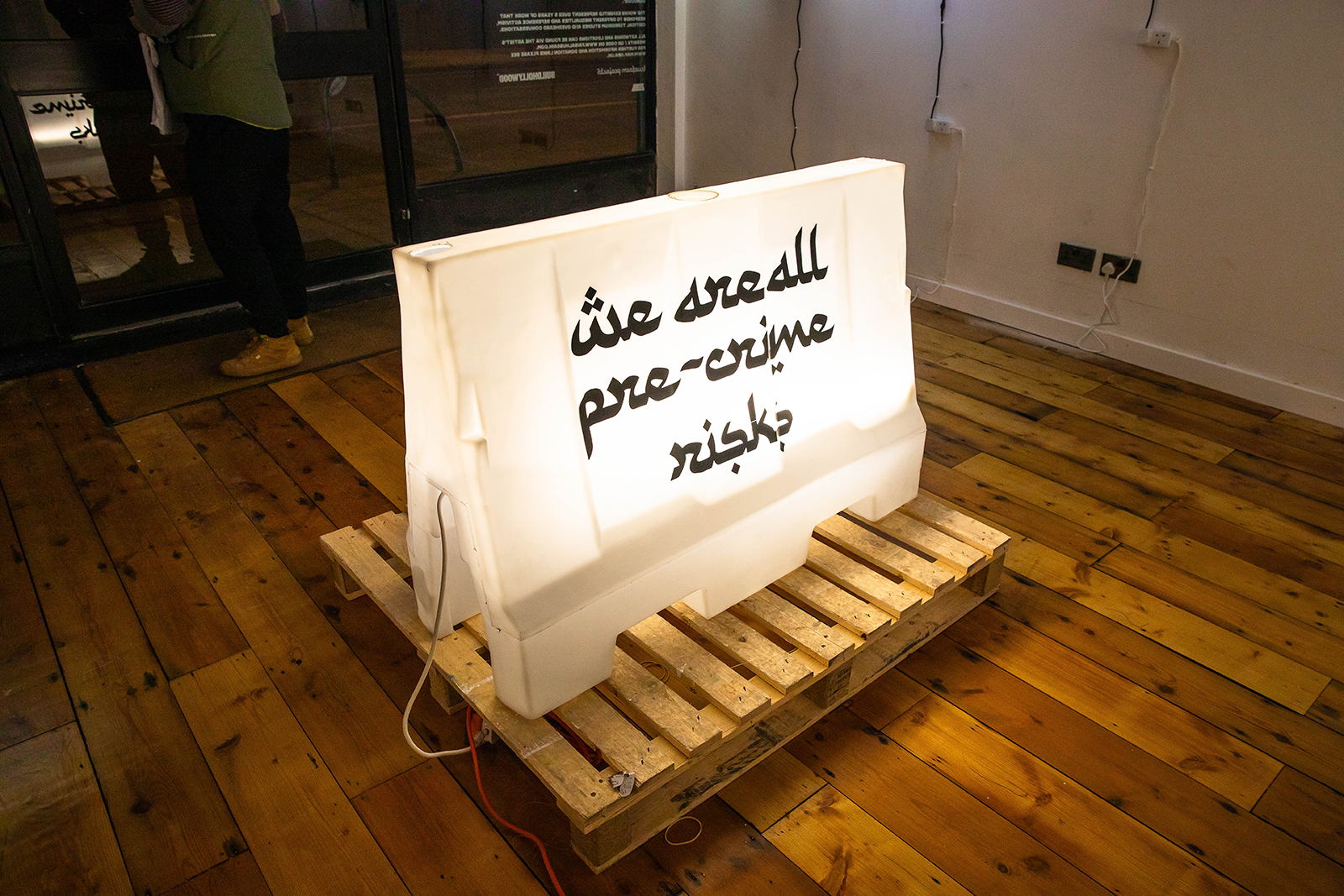

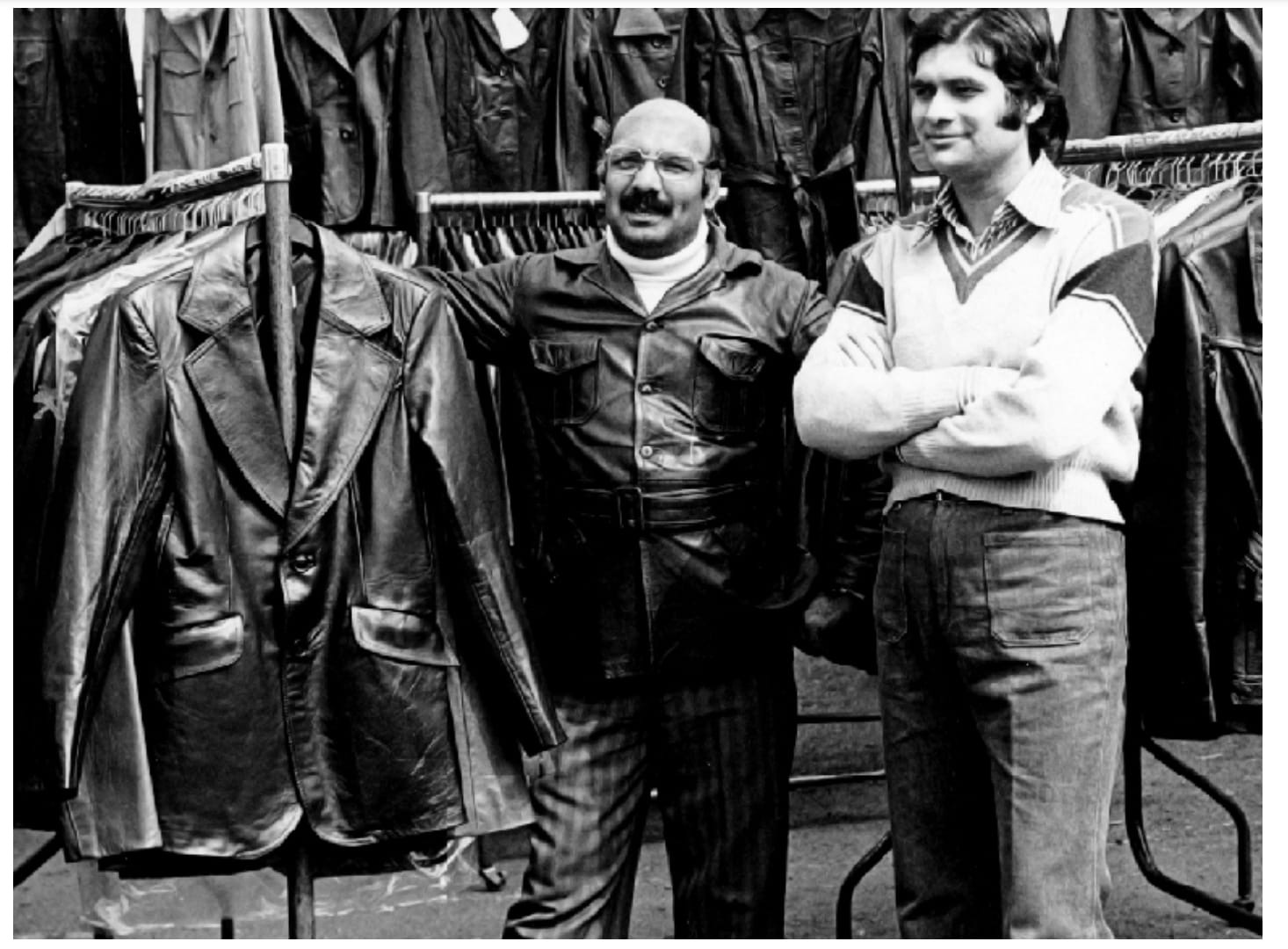

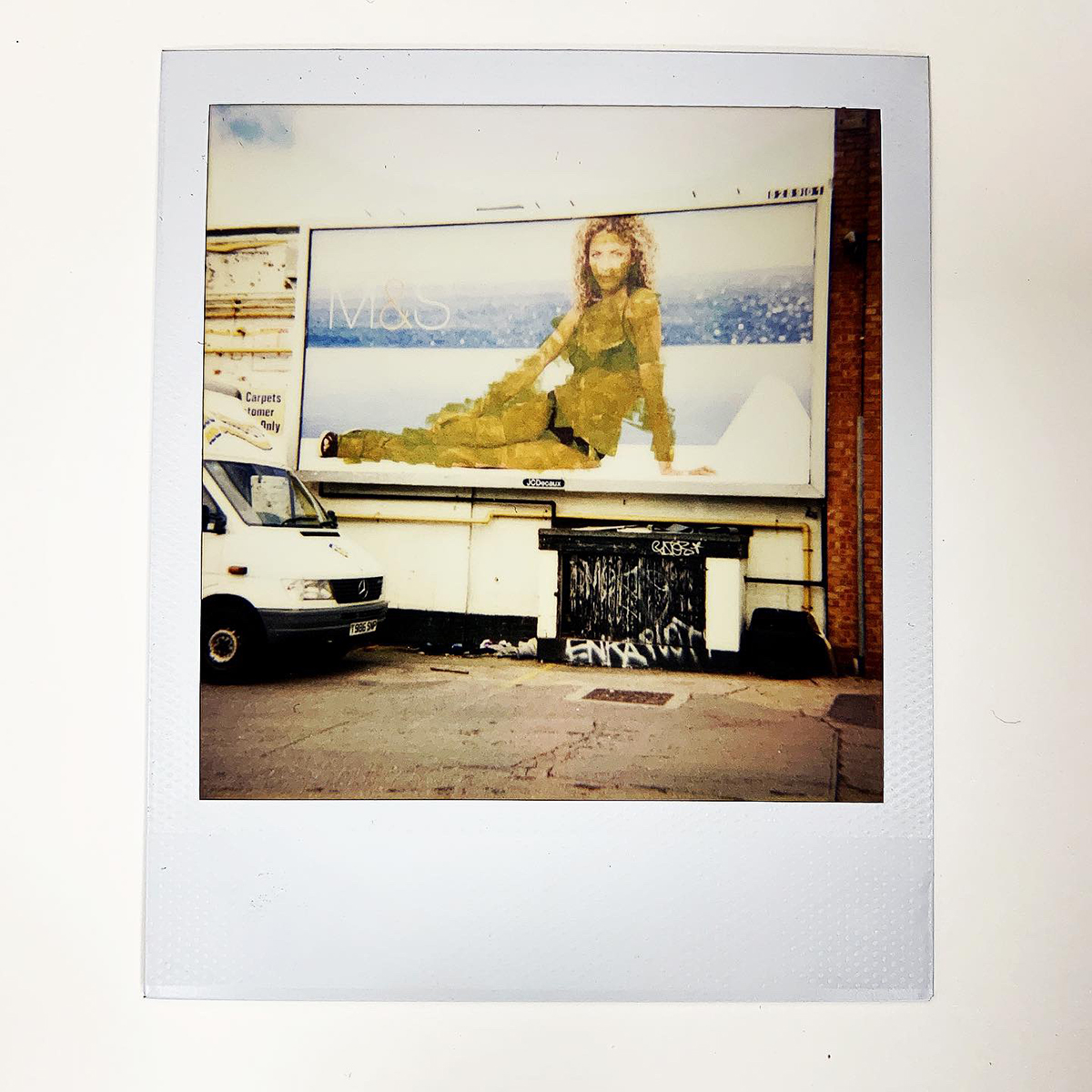

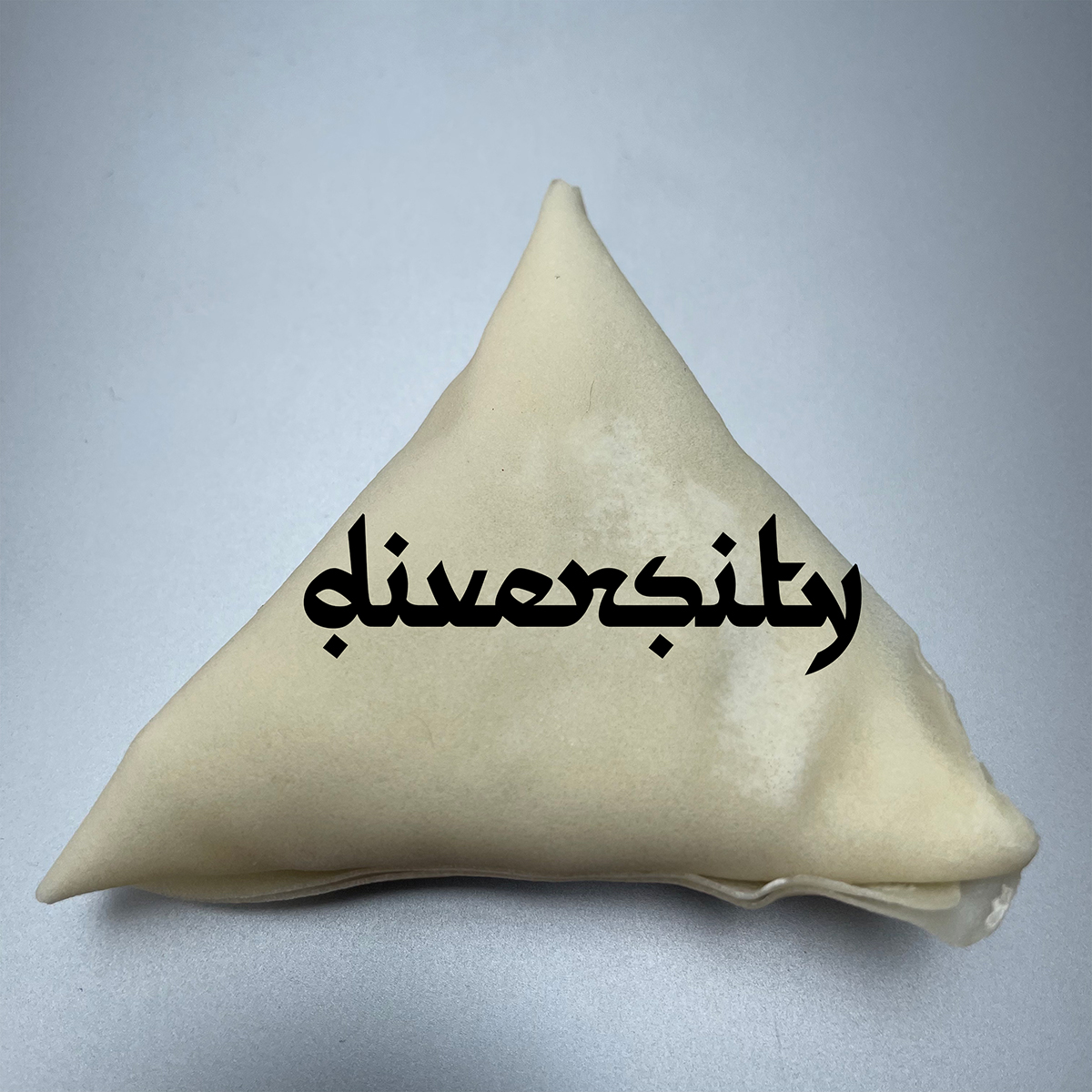

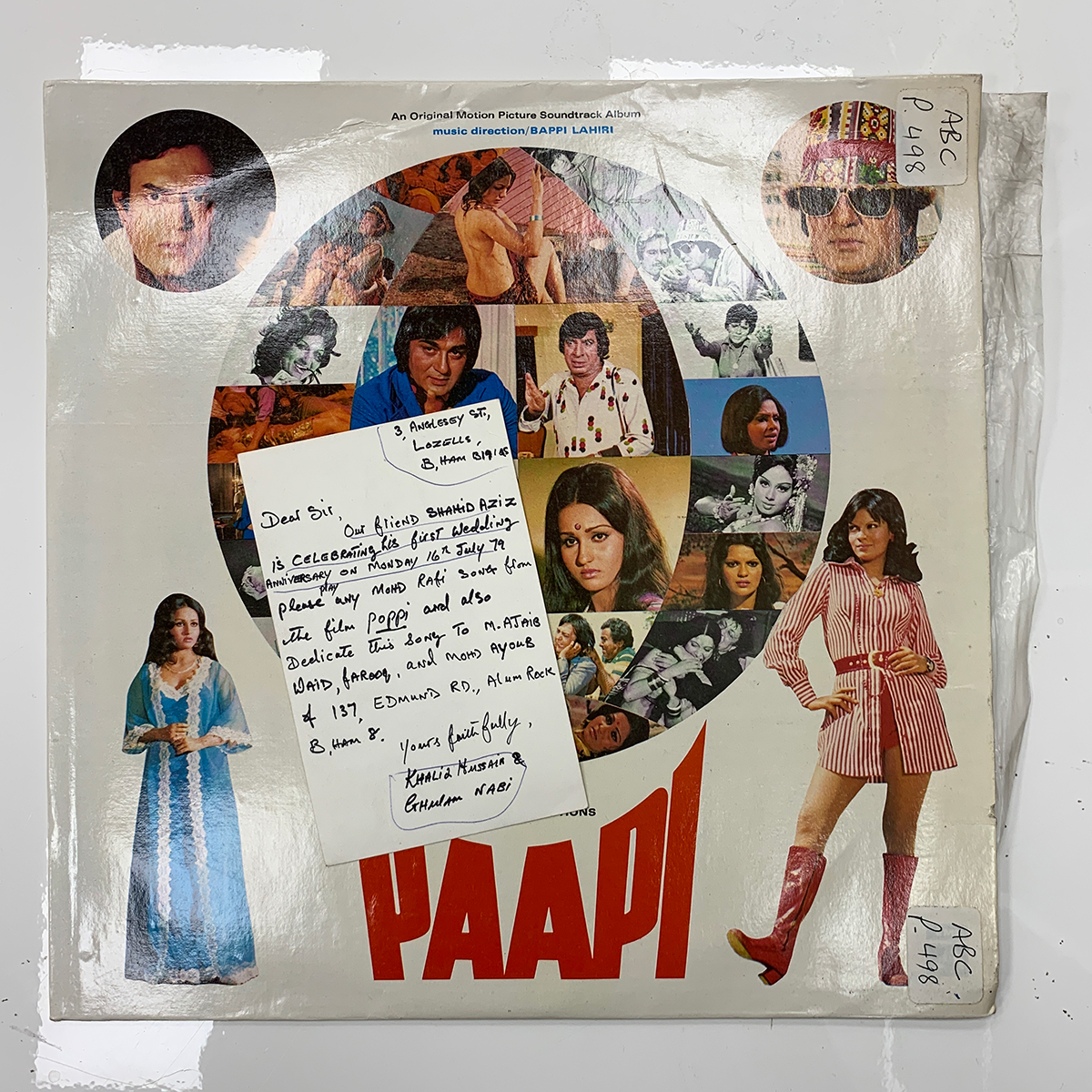

BUILDHOLLYWOOD is in locations surrounded by where people of many backgrounds have built their homes. I used to pick up leather jackets from Brick Lane in the 80s/90s. The first research I did was about the gentrification of the area when ‘Cereal Killer’ got vandalized in 2015, but many of the people that I spoke to were more concerned with the rise in Islamophobia which has exploded since. More recently, the redevelopment of parts of Brick Lane has been met with disdain from many who have lived and had businesses there for decades. The area has major importance for this history of many migrant communities, Huguenots avoiding persecution from France, Jewish communities escaping Russia and Eastern Europe, Irish migrants fleeing famine and the largest Bangladeshi community in the UK.

But hey, it’s more important that Tristan wants an ironic sweatshirt, a matcha latte, and a soapy IPA.*

Going back 10 years to your project F.light, you brought South Asian heritage to the high street through six lightbox signs in Birmingham. Can you tell me how that project came together and what you learned from it? Is there anything you’d do differently 10 years on?

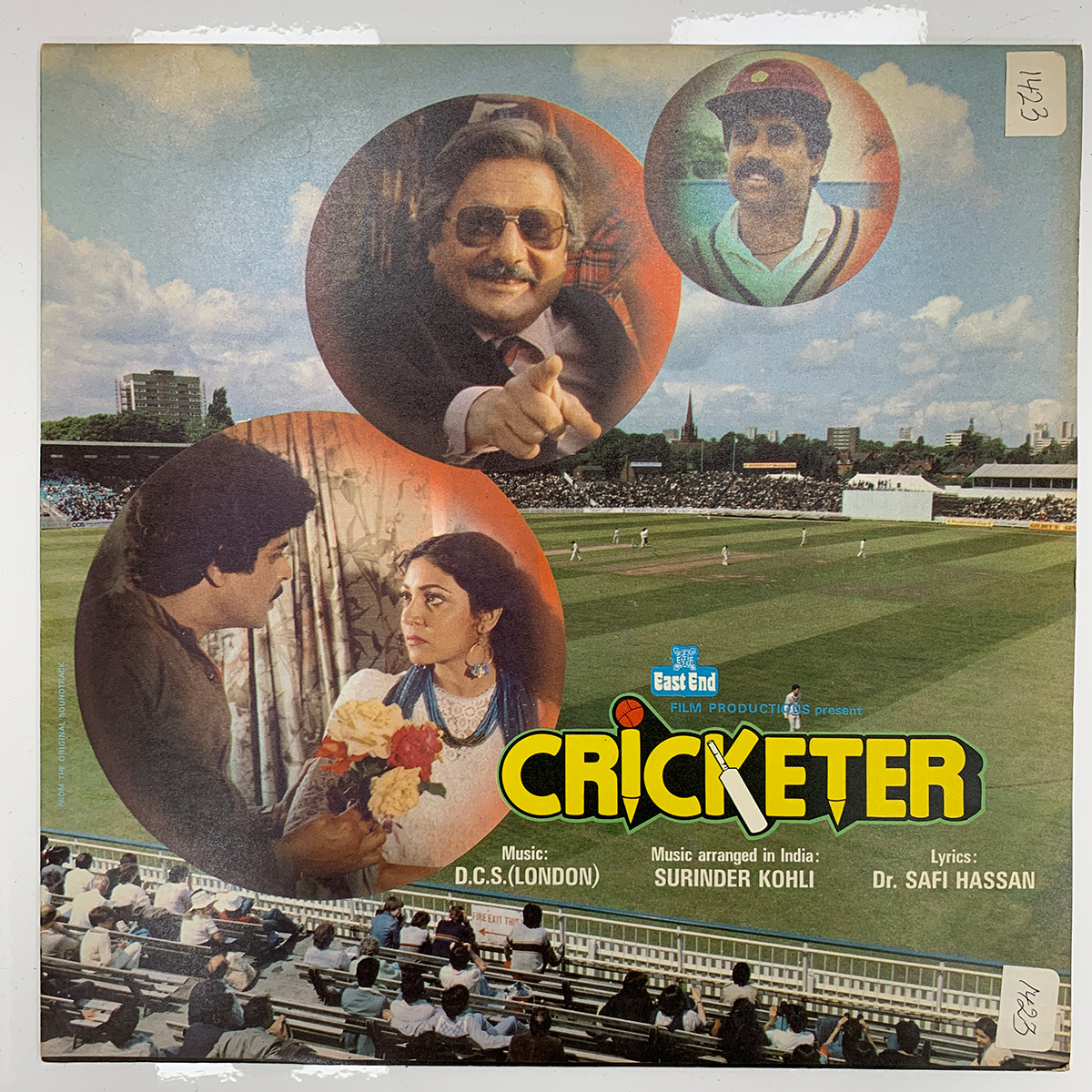

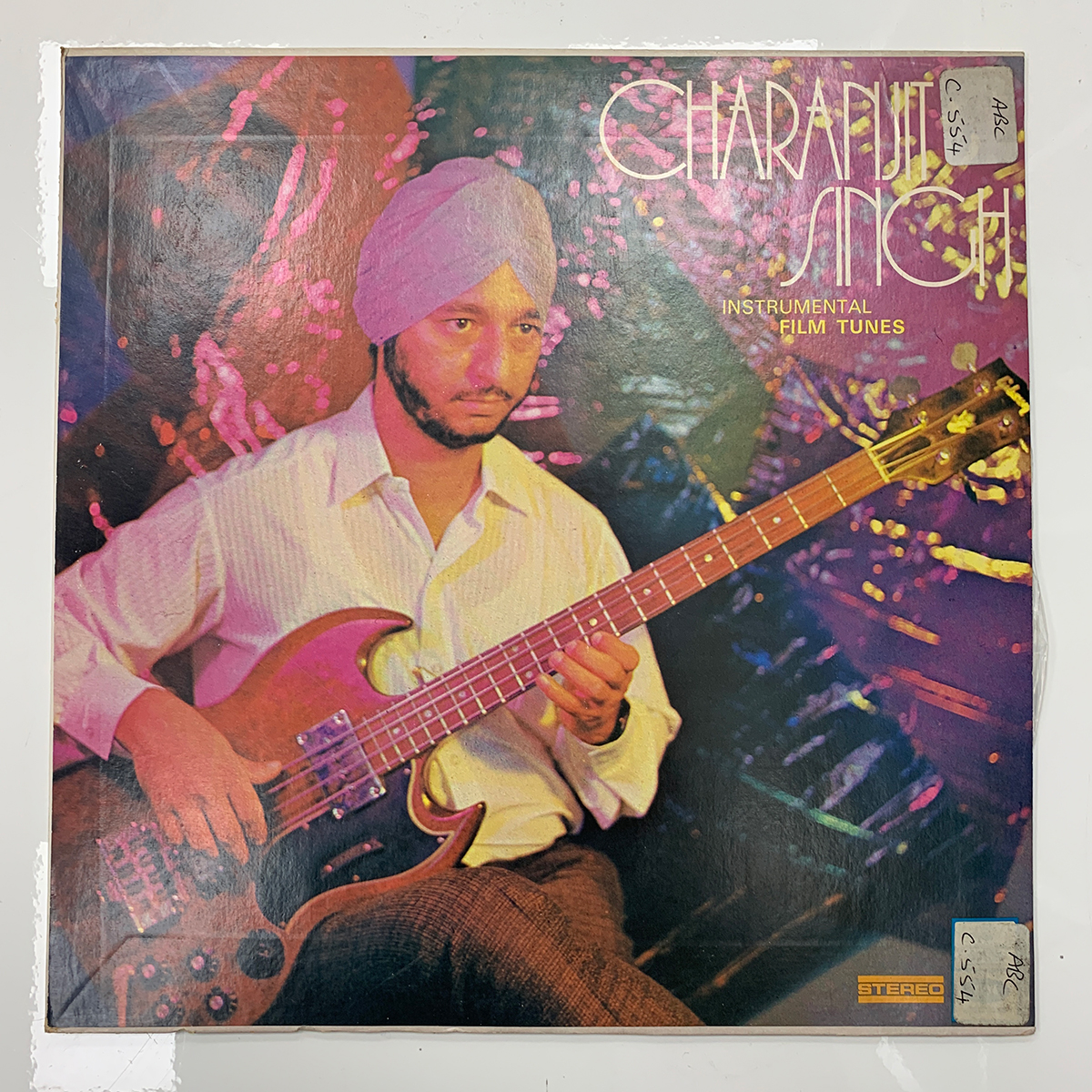

This work was about the parallels and differences between generations living here and what stories are passed on and which aren’t. After collecting information about all these different histories from 15 people, I thought that there needed to be further action to commemorate and mark contributions in the local area.

The project sat between heritage and artwork, decolonization, and public artworks, which were also meant to have an anti-racism slant to them allowing people to see some depth in their local history on the high street.

I learned that the diversity within peoples’ stories was so varied which provided a more plural aspect to each community and that even though there were parallels there were specific, real, and varied stories. With immense respect and sacrifice of many men who came to this country which is all but forgotten.

I don’t think I’d do anything differently 10 years on apart from being a bit more adventurous in scope and putting up more. It’s not like the xenophobia and prejudice have reduced, it’s only increased tenfold, at the time I said ‘Racism is the material for the work’ I now wish I hadn’t been so brash.