Things we love

Code Red: One last chance

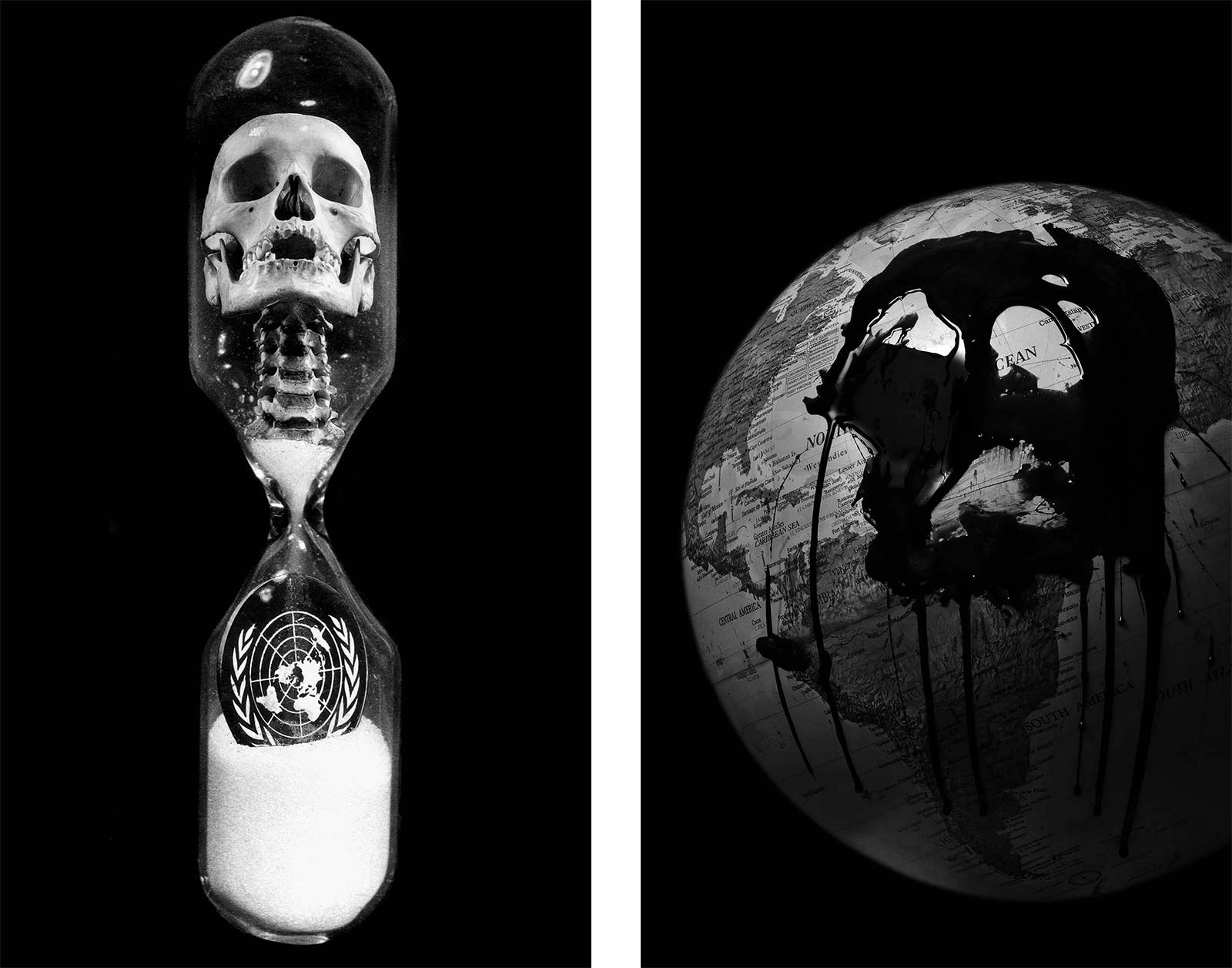

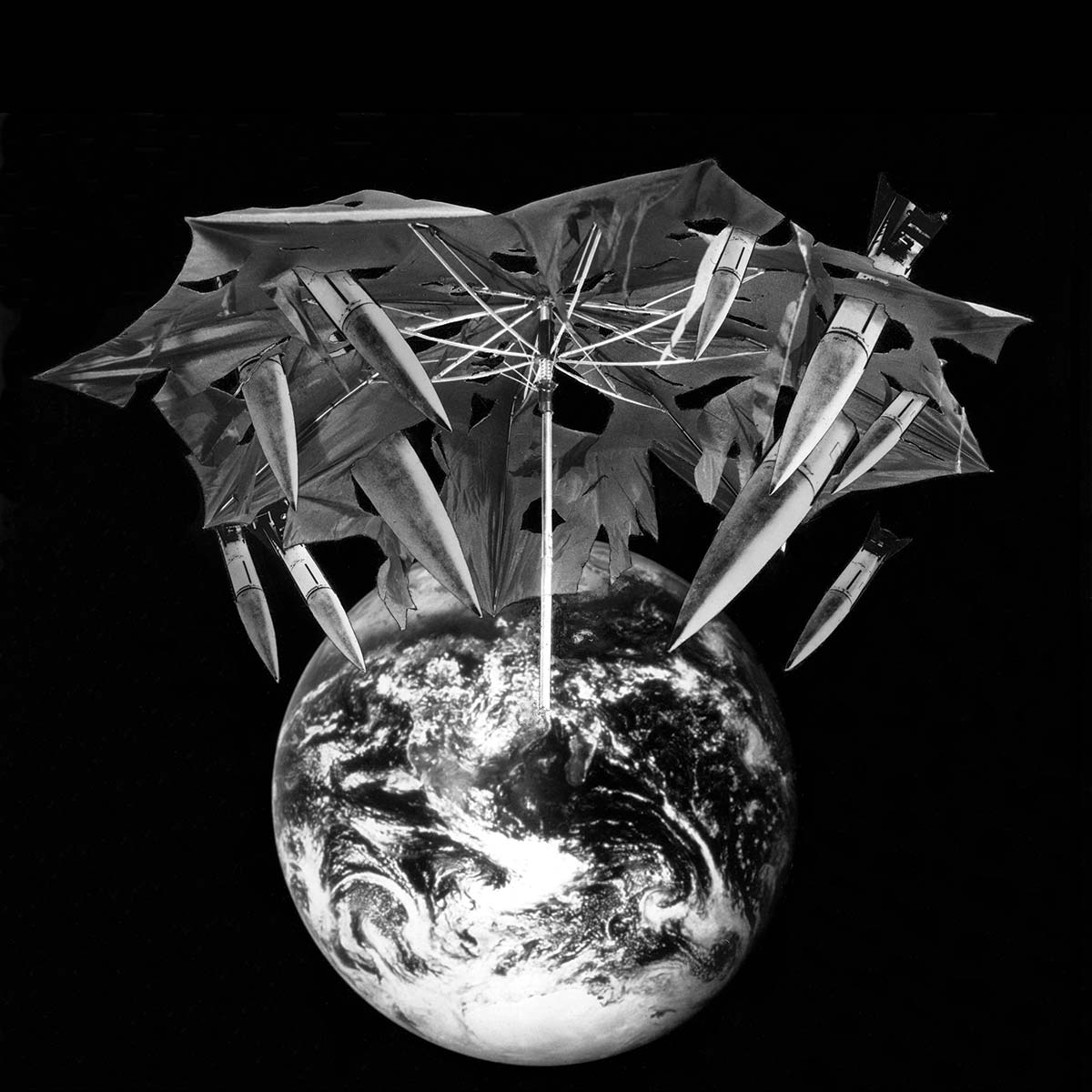

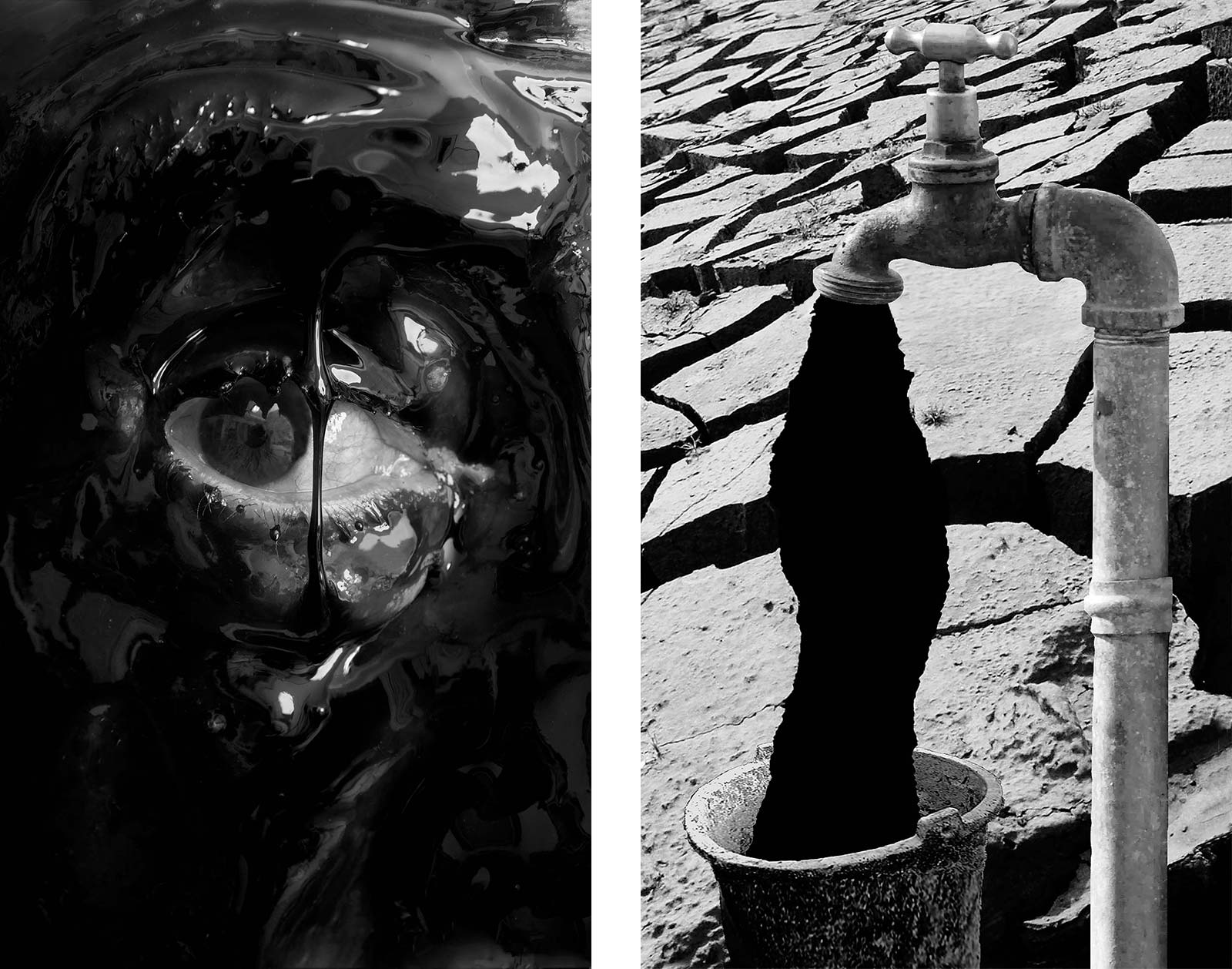

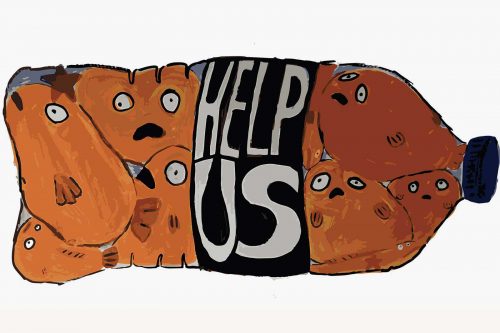

CODE RED is a print installation featuring 28 stark monochrome artworks by Peter Kennard for Street Level Photoworks, presented at Gallery 103 in Glasgow to coincide with the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference.

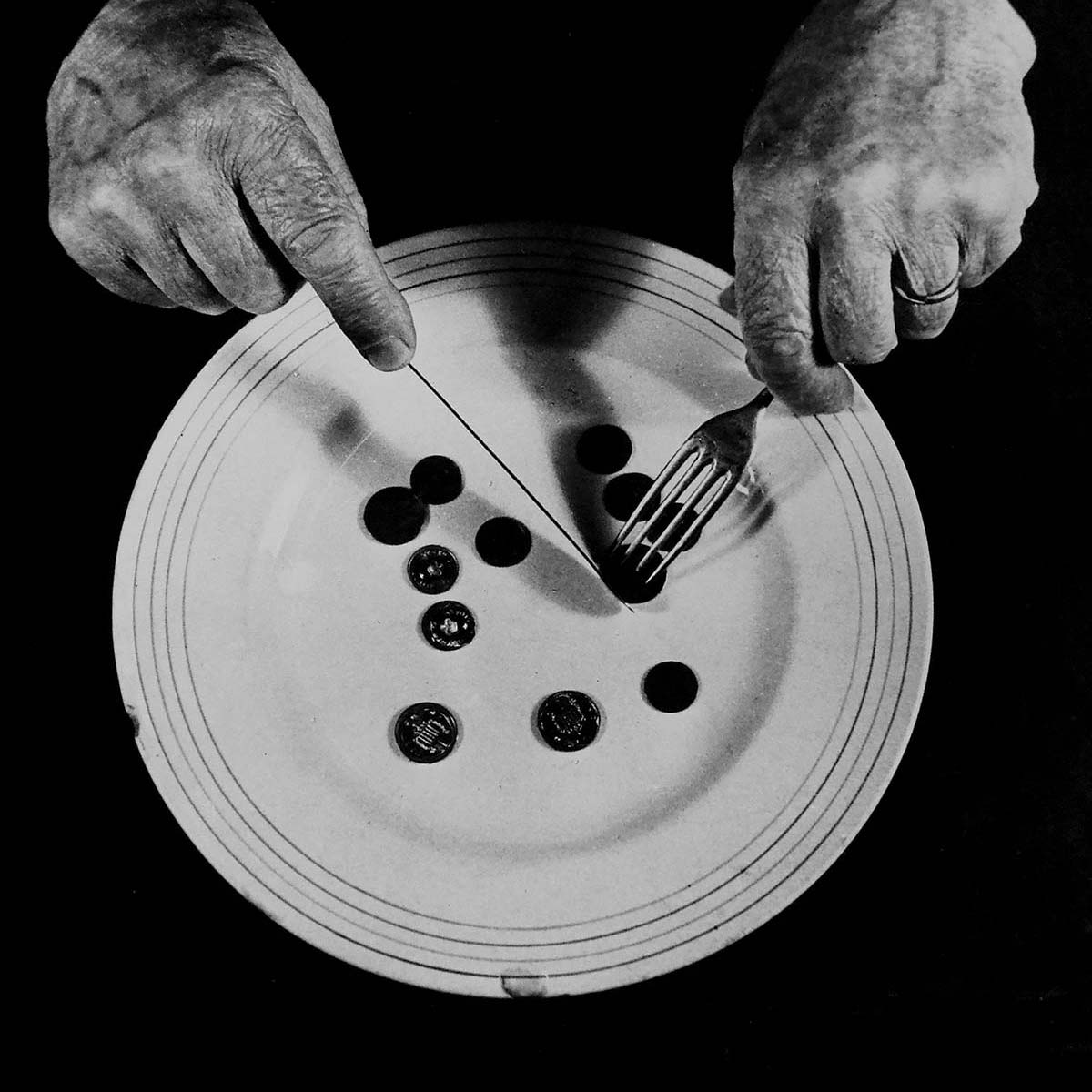

Impassioned, ambitious and furious, this extensive series of montages is bookended by images featuring black military style watch dials. ‘Past Midnight’ opens the show, economically apprising viewers as to the parlous state the planet and humankind finds itself in. Its watch hands mounted on a WW2 gas mask are nuclear missiles. The time reads 5 past midnight.

In August 2021 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published a report prepared by 234 scientists across 66 countries warning that human activity has resulted in atmospheric CO2 concentrations that are higher than any time in the past 2 million years. The United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres said the IPCC report was the ‘code red for humanity, the alarm bells are deafening and the evidence irrefutable’.

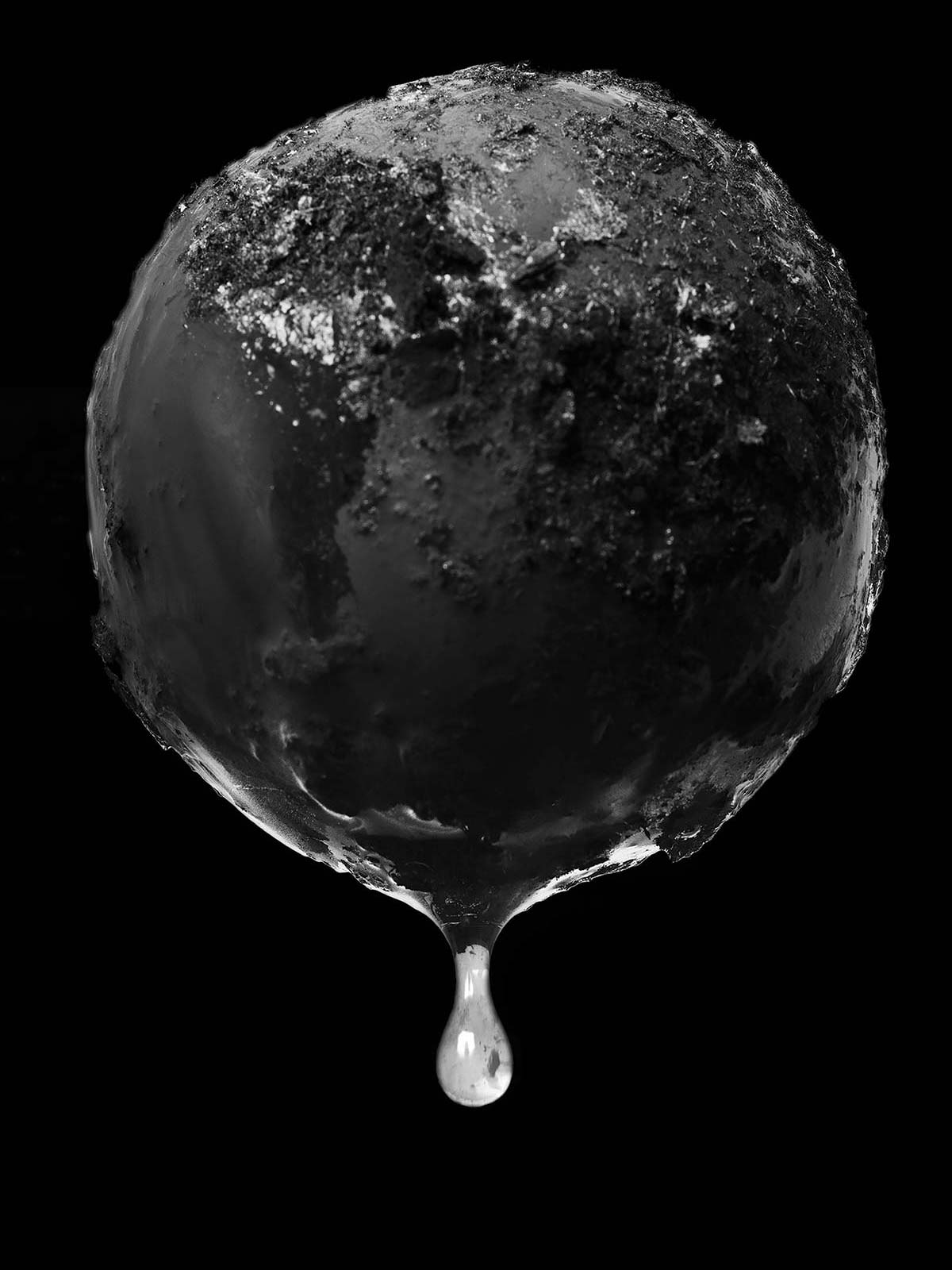

In the final image of the CODE RED series the watch dial this time is an image taken by Apollo astronauts in 1972. It shows planet earth as a whole, swathed in its diaphanous, swirling, life giving atmosphere. A hand reaches into the image frame, it’s holding onto a cord attached to the minute hand. The concluding work’s title ‘Pull Back’ reads both as a command and a desperate plea.

03.11.21

Words by